Partly because of prompt countermeasures by the Parliamentarians, Hopton’s anticipated support from the Devon Royalists failed to materialise, and, although he was able to chase Ruthven back into Plymouth and occupy Tavistock, the Royalist commander had no more substantial success to claim. Urged on by further promises of support, the Cornish Army advanced on Exeter, which Hopton had been assured would surrender without a fight. However, on arriving before Exeter on 18 November, Hopton found his summons firmly rejected, and, after an exchange of artillery fire, the Cornishmen were sufficiently roughly handled in a sally by the defenders to abandon their attempt and pull back to Tavistock.

With more optimism than solid grounds for confidence, Hopton turned his attention to Plymouth, and, with his headquarters at Plympton, established a number of outposts to blockade the town on its landward side. Some indecisive skirmishes followed, with Ruthven, by now being reinforced and supplied by sea, making initially unsuccessful attempts to break the Royalist blockade. Still hoping for support from Devon, Hopton and the Royalist High Sheriff of the county called upon the posse commitatus to muster at Modbury on 6 December. As was usually the case, only a few men appeared, and these, according to Hopton, were ‘so transported with the jollity of the thing that no man was capable of the labour, care and discipline’.

This jovial gathering was too good an opportunity for Ruthven to miss, and in a dawn sortie on 7 December he quickly dispersed the militia, Hopton, according to one account, narrowly escaping capture. His designs on Plymouth thwarted, Hopton withdrew to Totnes in largely pro-Royalist south Devon, and pillaged the surrounding countryside. The Parliamentarians meanwhile were strengthening the defences of Barnstaple in north Devon and raising troops in the area to combat a Royalist force mustering at Torrington.

Just before Christmas 1642, again optimistically believing hints of local Royalist assistance, Hopton made a renewed advance on Exeter. He was once more disappointed with the outcome. The Cornish lacked the strength fully to blockade the city, which had been reinforced from Plymouth by Ruthven. After a half-hearted assault had been repulsed on 1 January, the Royalists retreated slowly westwards, ‘in that bitter season of the year’, as Hopton ruefully put it . As they trudged back towards the Tamar, via Crediton, Okehampton and Bridestowe, the sullen Cornish foot were ‘through the whole march so disobedient and mutinous, as little service was expected of them if they should be attempted by the Enemy.’ Despite Hopton’s fears, however, when a party of Parliamentarian horse approached near Bridestowe, the Cornishmen promptly fell into rank and saw them off.

By 4 January 1643 the Royalist army was back in Cornwall at Launceston, its first invasion of Devon having ended in ignominious failure.

The initiative now passed to the Parliamentarians. Reinforcements, including three regiments of foot, under a new and more energetic commander, the Earl of Stamford, were on the way, and these reached Exeter on 6 January. Stamford’s plan was to unite his forces with those under Ruthven at Plymouth and, with a combined strength of 4,500 men, cross the Tamar and destroy the Cornish Royalists. Instructions were sent by Parliament for additional funds to be raised in Devon to support this force.

The Royalists were in a poor condition to meet the imminent threat of invasion. Many of their troops were mutinous through lack of pay, and lacked arms and ammunition. They were saved by a mixture of blunders by their opponents and an unexpected stroke of good luck. Ruthven, possibly anxious to capitalise on his initial success or, as is sometimes suggested, wishing to gain credit for defeating the Royalists before Stamford arrived, attacked the crossing of the Tamar at Newbridge with a mixed force of troops, including units from Dorset, Somerset and Devon, and a small Cornish Parliamentarian regiment of foot under Francis Buller. The Royalists had broken down the arches of the bridge, but whilst Ruthven’s musketeers exchanged fire with its Royalist defenders his horse and dragoons crossed at a ford below the bridge, chasing off a small group of enemy dragoons and capturing three or four of them.

Next morning, probably after effecting temporary repairs to the bridge, the Parliamentarian force crossed into Cornwall. In response the Royalist garrison of Saltash abandoned the town and withdrew through Launceston to join Hopton’s main force at Bodmin. Ruthven himself crossed by boat from Plymouth to join his troops at Saltash, bringing with him reinforcements, including Carew’s Cornish horse and his own Scots professional soldiers. Probably hastened by news of the Earl of Stamford’s imminent arrival at Plymouth, he pushed on to Liskeard.

At this point, what the Royalists would claim as the workings of Providence intervened on Hopton’s behalf. On 17 January stormy weather forced three Parliamentarian ships, laden with arms and ammunition — and, equally importantly, money — to seek shelter in Falmouth, where they were promptly seized by the exultant Royalists. With their contents, and £204 rapidly raised by Francis Bassett, Hopton was able to re-equip his men and provide them with all their pay arrears plus an additional fortnight’s wages in advance. A rendezvous was called the same day at Moilesborrow Down, where the five volunteer foot regiments, with a few horse and dragoons and some of the Cornish Trained Bands and posse comitatus were gathered, making a total of about 5,000 men.

Refreshed and revived, the Royalist Council of War met on 18 January at Lord Mohun’s house at Boconnoc, where their troops spent the night encamped in the park. The Council decided that their only hope lay in engaging Ruthven before he could be reinforced by Stamford, and around noon on 19 January the Royalists set off in search of the enemy.

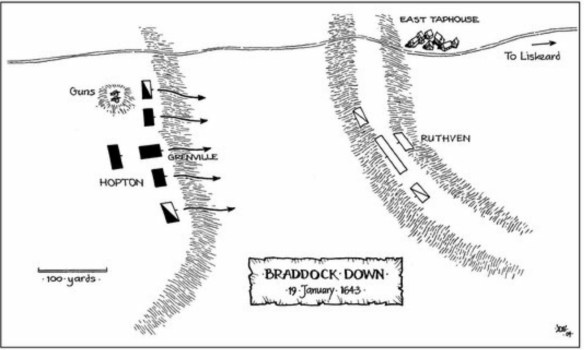

As Hopton’s men crested the hill above Boconnoc, their scouts sighted the enemy drawn up on rising ground on the eastern side of Braddock Down, just to the west of the present-day village of East Taphouse. The terrain consisted of two areas of heathland, with a few enclosures and areas of shrubs. Several prehistoric tumuli formed prominent features.

Both commanders seem to have been slightly surprised by the encounter. Ruthven had left Liskeard that morning, heading for Lostwithiel, and apparently believed the enemy to be in retreat. His march had been slowed by ‘narrow and very dirty lanes’ and, despite having Cornish Parliamentarians with him, he seems to have found difficulty in obtaining accurate information regarding the locality and Royalist movements. The Parliamentarian commander claimed later that he had been surprised when Hopton’s men emerged from the woods above Boconnoc, and after some skirmishing between opposing horse and dragoons the Parliamentarians fell back to the ridge just short of East Taphouse, and both sides began to deploy for battle.

The Royalists had simplified their confused command structure by requesting Hopton to command during the battle, and he drew up his forces on the west side of Braddock Down‘in the best order he could’. He had a slight advantage in numbers, with perhaps 5,000 men against a Parliamentarian force of 3–4,000. Both armies included troops of widely varying quality.

Hopton advanced a party of musketeers to line the hedges of some small enclosures to the front of his main position and drew up his body of foot on the ridge itself, in two lines, with horse and dragoons stationed on his flanks. The Parliamentarians, who probably had a slight numerical advantage in horse over Hopton’s 250 troopers, deployed in similar fashion on the north-east side of Braddock Down, keeping a reserve of foot in the hedges behind their main position.

The opposing forces were within musket shot of each other, and neither at first showed any desire to quit their strong position and launch an attack. About two hours of largely ineffectual exchanges of musket fire between the opposing forlorn-hopes in the hedgerows followed, until Hopton decided to take the initiative.

Two light guns, or drakes, belonging to Lord Mohun were dragged up the hill from Boconnoc and advanced within range of the enemy, concealed behind a party of horse. With the Parliamentarian artillery still bogged down in the lanes leading from Liskeard, Hopton decided to launch a general assault.

Prayers were said at the head of the divisions of foot and then, after the drakes had fired a couple of rounds, the Cornish foot advanced down one slope and up the other towards the Parliamentarian position. The assault was headed by Sir Bevil Grenville’s Regiment of Foot, with the less reliable Trained Bands and militia in support. The horse charged on both wings.

Enemy resistance quickly collapsed. Ruthven’s first line broke with little fighting. The reserve, behind the hedges, at first attempted a stand, but when their mounted officers made off the troops joined the flight.

Sir Bevil Grenville wrote an exultant account of the action to his wife:

My dear love,

It hath pleased God to give us a happy victory this past Thursday being the 19th of January, for which pray join me in giving God [thanks]. We advanced yesterday from Bodmin to find the enemy, which we heard was abroad; or, if we miss finding him in the field, we were resolved to unhouse him in Liskeard or leave our bodies in the highway. We were not above three miles from Bodmin when we had view of two troops of their horse to whom we sent some of ours which chased them out of the field, while our foot marched after our horse. But night coming on we could march no further than Boconnoc Park where (upon my Lord Mohun’s kind motion) we quartered all our army that night by good fires under the hedge.

The next morning (being this day) we marched forth at about noon, came in full view of the enemy’s whole army, upon a fair heath between Boconnoc and Braddock Church. They were in horse much stronger than we, but in foot we were superior as I think.

They were possessed of a pretty rising ground which was in the way towards Liskeard, and we planted ourselves on such another against them within musket shot, and we saluted each other with bullets about two hours or more, each side being willing to keep their ground of advantage, and to have the other come over to his prejudice. But after so long delay, they standing still firm and being obstinate to hold their advantage, Sir Ralph Hopton resolved to march over to them and to leave all to the mercy of God and valour of our side.

I had the van; and so, solemn prayers in the head of every division, I led my part away. Who followed me with so good courage, both down the one hill and up the other, that it struck a terror in them. Whilst the seconds came up gallantly after me, and the wings of horse charged on both sides.

But their courage so failed them as they stood not our first charge of foot but fled in great disorder and we chased them divers miles. Many were not slain because of their quick disordering, but we have taken about six hundred prisoners. Amongst which Sir Shilston Carmedy is one, and more are still brought in by the soldiers; much arms they have lost, eight colours we have won, and four pieces of Ordnance from them.

And without rest we marched to Liskeard and took it without delay, all their men flying from it before we came.

And so I hope we are now again in the way to settle the country in peace . . . Let my sister and my cousins of Clovelly, with your other friends, understand of God’s mercy to us. And we lost not a man . . .

The Parliamentarian rout was apparently hastened when the townsmen of Liskeard attacked their rear. Hopton suggested that the Cornish deliberately spared many of the fugitives, possibly because some of them were their pre-war neighbours, but the final tally of prisoners was at least 1,250 men, with perhaps 200 dead. Two Parliamentarian demi-cannon and a number of smaller pieces were captured, probably abandoned in the lanes leading to Liskeard.

As the victorious Royalists occupied Liskeard that night, Ruthven fled to Saltash, which he garrisoned before decamping to Plymouth. Pressing his pursuit, Hopton stormed Saltash on 22 January, taking 140 prisoners. Meanwhile a second Parliamentarian force under Lord Stamford had begun an advance on Launceston, but, on learning of the rout at Braddock Down, it retreated to Plymouth. Cornwall was for the moment clear of the enemy and the initiative was back in Hopton’s hands.