All the plans and progress implemented thus far, whether in France or the United States, would come to naught without the aircraft necessary to conduct offensive operations. Upon this one issue hinged the success or failure of the entire venture. Once the Navy Department reached the decision to proceed with plans to establish a bombing group in Europe, it became abundantly clear to planners in Washington that no night bombers would be forthcoming from America. As early as April 4, 1918, Admiral Sims was advised by cablegram to secure them abroad, if possible. He responded on the 21st, passing on Captain Cone’s request for authority to place a contract with the Italians to purchase needed Capronis in exchange for Liberty motors and raw materials.

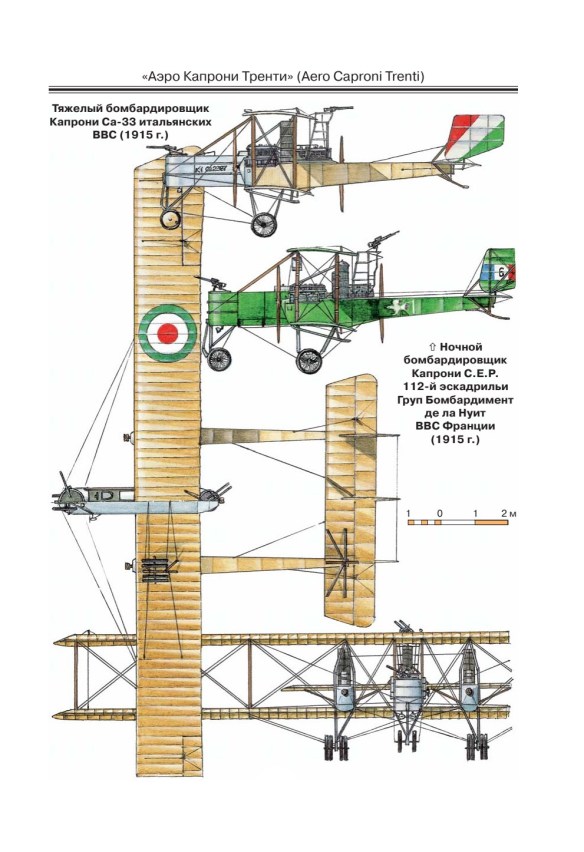

Cone’s involvement with Caproni began late in 1917 when representatives from the firm offered to supply its aircraft to the U.S. Navy in Europe. Plans to obtain bombers for work in Flanders were initiated in February 1918, when Lt. Edward McDonnell, then a member of Cone’s staff in Paris, was dispatched to Italy to investigate aviation conditions there, paying particular attention to bombing operations and aircraft. While in Italy, McDonnell met with Signore Caproni on several occasions, toured his factory, and made flights in the industrialist’s planes, including a three-engine, 450-hp bomber. Designated the Ca. 3 by the Italian Army, it was the most numerous Caproni bomber in use. During one of his test flights the huge machine—with an Italian pilot at the controls—performed a complete loop. McDonnell rightly considered this to be a remarkable feat for such a large plane. The 450-hp bomber was powered by three very reliable Isotta-Franschini motors. Rated at 150 horsepower, the motor had an excellent record and performed well at the front. The Ca. 3 was highly maneuverable (as indicated by its ability to complete a loop) and capable of carrying a 1,000-lb bomb load to an altitude of 15,000 feet.

McDonnell was so enthused by the plane that he requested permission to fly one from Milan to the front where he spent time with a bombing squadron and even took part in a raid behind Austrian lines, serving as the front cockpit gunner. After returning to Milan, McDonnell met again with Signor Caproni to discuss a new airplane then under development, a 600-hp model powered by three 200-hp Fiat engines that was reputed to have nearly double the bomb-carrying capacity of the Ca. 3 and a top speed of 105 mph.

After returning to France in mid-March, McDonnell was sent to the northern front and attached to 7 Squadron, RNAS, where he flew as a front and rear gunner in combat raids behind the front lines. As a result of this experience, he came away believing that the 600-hp Caproni under development seemed to have advantages over the Handley Page then being flown by 7 Squadron. This information must have been passed to Admiral Sims when McDonnell traveled through London on his way to Washington, D.C., at the beginning of April. And it was certainly forwarded to naval authorities in Washington after he arrived, ensuring the ready acceptance of Cone’s proposal to obtain Caproni aircraft for the Northern Bombing Campaign.

With Sims’ approval in hand, Cone dispatched Lt. (jg) Harry F. Guggenheim and Spenser Grey—now bearing the rank of a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Air Force—to Rome to negotiate the purchase of Caproni’s aircraft with the Italian government. Guggenheim, an experienced businessman, was the son of one of the wealthiest men in America. In 1917, anticipating his country’s entry into the First World War, he purchased a Curtiss flying boat and learned to fly. After America entered the war, he helped form a naval aviation unit in Manhasset, New York, and was commissioned as a lieutenant, junior grade, in the U.S. Navy Reserve Force. He served as Cone’s business aide until March 1, 1918, when he was appointed director of the Administrative Division in charge of all business and industrial activities. Guggenheim was the logical choice to negotiate the contract and was ordered to Rome to work with Grey, who was already in Italy as part of a commission studying the question of establishing air bases for the U.S. Navy.

Even before their arrival in Italy, the Navy’s plan to acquire land bombers for use against the enemy ignited a firestorm at the U.S. Air Service’s European headquarters then under the command of Brig. Gen. Benjamin D. Foulois. Relations between the two forces were already strained over a dispute between Cone and Foulois concerning the structure and membership of the Joint Army-Navy Aircraft Committee that had been created to organize and coordinate aircraft procurement activities of U.S. armed forces abroad. What should have been a simple administrative matter became a major issue when Foulois insisted on a majority representation for the Army, despite General Pershing’s instructions that three Army and three Navy members be appointed. After the first few meetings in December 1917, it became clear that Foulois was uncooperative, forcing Cone to request dissolution of the committee.

Foulois complained bitterly in April when he learned that 734 scarce Liberty engines had been allocated to the Navy, asking his superiors in Washington why these engines, which were desperately needed by all of the Allied air services, had been given to the Navy. He hit the ceiling several weeks later when he discovered that the Navy was planning a separate bombing offensive against enemy submarine facilities using land planes operated from bases on the Western Front. “Present military emergencies,” he wrote in a cable sent to Washington under Pershing’s signature on May 3, “demand that the air services of the allied armies be given all priority in advance of the air service of the allied navies. The air supremacy of the Allies on the western front is only held by a narrow margin at the present.”

When this cable was sent the Germans’ spring offensive was in full swing and presented a grave danger to the Western Front. Although the enemy’s offensive toward the Channel ports had been contained, in the center of the Allied line, the Germans still held the initiative. Nevertheless, the War Department, acutely aware of the need to keep the sea-lanes to Europe open, reaffirmed the Navy’s bombing measures against the enemy’s submarine bases, cabling back:

Priority to United States Navy Air Services for aviation materials necessary to equip and arm seaplane bases was approved by War Department, November 1, 1917. On March 17, 1918, War Department approved request of Navy Department that 80 two-seater pursuit planes be delivered to Navy on or about May 15, to be used in bombing operations. On May 2, War Department acceded to request of Navy that this number be raised to 155, but deliveries distributed over longer period. On April 10, War Department concurred with Navy Department that operations against submarines in their bases was purely naval work. Seven hundred and thirty-four Liberty engines have been allocated to Navy for delivery prior to July 1. No allocations have been made after that date. Navy Department for last year has left matter of engine production entirely in the hands of the War Department, and is in this respect wholly dependent for the operations of their Aviation Service. War Department, May 7, carefully reviewed entire matter, in view of your cables, and had decided that no changes can be made at present in priority decision.

Lieutenant Guggenheim arrived in Rome amidst the imbroglio surrounding the issue of the Navy’s land planes. One of his first tasks required meeting with Capt. Fiorello La Guardia, the Army’s Air Service representative in Italy. La Guardia, a first-term congressman from New York City, had joined the Air Service in the summer of 1917 and learned to fly in Italy at Foggia. This was something of a homecoming for the Italian-American airman, for Foggia was his father’s birthplace. In February 1918, La Guardia was designated to represent the Joint Army-Navy Aircraft Committee in Paris with the Italian authorities. This brought him into contact with Lt. Cdr. John L. “Lanny” Callan, Cone’s hand-picked representative in Italy. Callan—a native of Cohoes, New York—was an ideal selection for the post having a long and intimate association with Italian aeronautics. While employed by Curtiss, he met Capt. Ludovici De Filippi, who later played a critical role in the Italian Navy’s Mediterranean aviation operations. Following the outbreak of war in Europe, Callan sailed to Italy as a Curtiss sales representative. In January 1915, authorities there requested that Callan oversee establishment of their first aeronautics school at Taranto. Curtiss granted permission and in February “Lanny” became chief instructor and assistant to the commandant of the facility. After extensive military service in Italy, he returned to the United States and joined the Navy.

In early March 1918, while plans were being formulated for a bombing campaign against the U-boat bases, Cone asked Callan to make inquiries regarding the Italians’ ability to produce Capronis. Callan replied that eight factories were available. These inquiries brought Callan into contact with La Guardia, who was also seeking bombers on behalf of the Army’s aerial effort in Italy. Previous efforts to obtain Capronis for the Air Service had been initiated in August 1917 when the Bolling Mission first visited Italy but were never fulfilled in part because the country lacked the materials needed to construct them.

At first Callan assumed he and La Guardia could work together amicably, as both had a vested interest in expediting pilot training and production of Caproni aircraft. In a letter to Cone dated March 27, 1919, he reported being able to utilize La Guardia as an alternate conduit of information from the Commissary General of Italian Aeronautics Eugenio Chiesa. Callan met La Guardia a second time in late March, when the New Yorker urged completion of a naval air station on the Adriatic as a spur to Caproni production. At that time, Callan observed that “La Guardia may be a politician, but he is certainly a very influential one here.”

At this juncture, the Navy offered to supply lumber and other materials for its own orders, but La Guardia accused the sailors of playing foul because they controlled transatlantic shipping. He immediately launched a lobbying program that proved highly offensive to Cdr. Charles R. Train, the U.S. naval attaché in Rome. Train informed Paris that his efforts “were frustrated and position greatly embarrassed by the actions of Captain La Guardia,” who undercut the attaché by personally interfering with the Commissary General of Italian Aeronautics. The congressman, according to Train’s letter, claimed that Navy representatives had no authority to negotiate, nor could they guarantee shipments.

La Guardia played a double game, however. On one hand he did everything he could to sabotage the Navy’s efforts to procure Capronis; on the other he tried to placate the Italian authorities by encouraging the Navy’s intentions to operate in the Adriatic. Because the U.S. Army had no plans to employ Capronis south of the Alps, the Italians had little incentive to fill the Army’s orders for the scarce bombers. If the Navy conducted real combat operations on the Venetian front or elsewhere, however, local authorities might be more amenable to allocating aircraft to the Americans.

Despite the personal animosities that arose between La Guardia and his Navy counterparts, Lieutenant Guggenheim was able to negotiate an agreement—known as the May 10 agreement—with Signor Chiesa that provided for the purchase of thirty aircraft to be delivered in June and July, and eighty more in August, twenty in September, and twenty per month thereafter. In return, the U.S. Naval Forces, Foreign Service would recommend to Admiral Sims that high priority be given to both purchases and shipment of raw material ordered by the Italian government from the United States for the manufacture of aircraft and sufficient raw material would be shipped to Italy by the Navy to compensate for supplies diverted to the planes manufactured for U.S. naval aviation in Italy. The parties never formally signed the agreement, however, and despite several arbitrary modifications made by Signor Chiesa, Italy proved unable to fulfill the terms of the deal.

As the weeks passed there was little movement on either the production or training front. Competition between the services intensified and acerbic charges and countercharges flew back and forth. Cone in Paris, sensing that trouble was brewing, sent word to Capt. Noble Irwin in Washington at the end of May that La Guardia—as a New York politician—was principally concerned in pushing a large general project looking toward a campaign in Congress. He remained decidedly unenthusiastic about working with the Italian-American airman, warning that his people in Rome believed La Guardia had used “underhanded methods” and tried to oppose the Navy’s plans to obtain Capronis.

Word of the discord quickly got back to AEF headquarters—perhaps carried by La Guardia himself, who visited Paris in early May and, as the Navy believed, spread false reports of the negotiations with the Italians. In response, Pershing penned a personal letter to Sims describing a “lack of coordination between officers who are handling the U.S. Army and Navy Air Service in Europe.” He charged that there were instances when the services had come into competition in obtaining material, creating an unfavorable impression with the Allies that might affect other areas of cooperation. Somewhat taken aback by these charges, Sims wished to respond to the Army chief and solicited Cone’s “immediate” opinion.

Cone replied without delay, dispatching a cable to Sims the next day. He had already shown the admiral’s communication to Col. Halsey Dunwoody, assistant chief of the Air Service for supply, who asserted, “perfect coordination between our offices exists” in all technical and supply questions. Cone recalled that when he first arrived in France cooperation at all levels had been very good, but recently “it has been impossible to get in close touch with the Chief of the Air Service [Foulois],” another Navy nemesis. He denied that the services competed for material, stating that everything was obtained through the Franco-American Mission and the Army General Purchasing Board. With regard to the Caproni contretemps, the likely source of Pershing’s comments was a rat named La Guardia. Cone worried that close cooperation meant letting the War Department handle the Navy’s business, something he did not believe them capable of doing.

Meanwhile, the Air Service experienced its own internal discord, with General Foulois in particular. To remedy this situation, Pershing appointed Brig. Gen. Mason M. Patrick as new chief of the AEF Air Service in late May, moving Foulois to another assignment. Patrick and Cone then sat down to thrash out various issues. Cone offered to let the Army conduct negotiations for Capronis, but objected to La Guardia’s involvement. Patrick stood by his troublesome subordinate, but promised the New Yorker “would faithfully care for the Navy’s interests.” Attempting to put the squabbling behind them, the senior officers drafted a joint memorandum on May 31 addressed to the, Italian Aeronautical Mission Paris, declaring that the Army would represent Navy interests in Rome and they would use their combined efforts to secure raw materials for Italy. Any previous agreements between the Navy and the Italian government remained in force.

Part of the plan to utilize Italian bombers required sending Navy mechanics and engineers to Caproni, Fiat, and Isotta Fraschini factories. Lt. (jg) Austin Potter, the officer in charge of the Fiat and Caproni divisions, spent weeks studying at Italian factories and flying fields, where he subsisted on a diet of pasta, goat milk ice cream, and mutton of “uncertain age but unmistakable flavor.” A keen observer of the local scene, he described Fiat shops filled with soldiers returned from the front, those with influential friends, a few youths, and bloomer-clad, black-frocked young women. Work hours stretched from 7:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., with one and a half hours off for lunch. Everyone labored on a piecework basis, with maximum earnings of 10 lire per day—equivalent to about $1.35 at that time.

To Potter, manufacturing methods used in the Italian factories seemed primitive. Much of the work was being done by manual labor that would have been performed by precise machine tools in the United States. He decried the inadequate inspection of machining and assembly operations, and was critical of the working drawings prepared by the Italian engineers, which lacked exact tolerances. Instead, the drawings contained symbols, squares, circles, indicating “force fit,” “tight fit,” “easy/sweet fit,” and “running fit,” and so forth and so on.

While American mechanics studied in various factories, fifteen Navy pilots led by Lt. (jg) Sam Walker reported to the aviation school at Malpensa in early June. The largest training facility in Italy with perhaps three hundred officers under instruction, Malpensa was situated forty-five minutes north of Milan by electric trolley. The airfield, about three miles square, lay in the stunningly beautiful lake country. During practice flights, students often passed over Lake Maggiore and Lake Como, ascending into the foothills of the Alps. American trainees lived with Italian officers and followed the same rules and regulations as their hosts. Accommodations were clean and comfortable, but the flying schedule differed greatly from that employed in the United States. Instruction began at 5:30 a.m. and continued until 10:30 a.m. Next, everyone sat down to a large meal, followed by a lengthy nap lasting until late afternoon, when instruction resumed, sometimes until ten in the evening. All this was designed to avoid the intense midday heat.

The continued lack of Caproni deliveries, however, cast a pall over the training program. What was the use of learning to fly the things, after all, if none could be supplied. The delivery issue was further clouded by the Italians’ reluctance to provide accurate or timely information on when bombers would be available. Unresolved problems limited output so that very few planes were produced, perhaps thirty to forty in June, and forty to fifty in July; far too few to meet the competing needs of all of the Allied air services.

While sensible in terms of presenting a united front with Italian authorities, the May 31 Army-Navy agreement only inflamed suspicions of the airmen of both services stationed in Italy and cooperation proved short-lived. La Guardia, according to Commander Train, rarely visited Rome and proved nearly impossible to contact. Word filtered down that the congressman connived at Malpensa for Army aviators to receive priority training. In a letter to Robert Lovett at Paris headquarters, Callan charged that “La Guardia was profuse in his denials, but Train doesn’t believe him.” Sam Walker had a particular bone to pick, reporting that “La Guardia was all for the Army . . . letting the Navy twiddle its thumbs.” Callan requested that Walker keep him informed, as “it was very important for us to know whether he is working for us or against us.” Callan approached the Italian Ministry of Marine and received assurances that the major had been instructed not to interfere. Well aware of the criticism, the embattled congressman attempted to set the record straight with a lengthy communication to General Patrick. La Guardia claimed the Navy acted “so queer and unfair down here,” that Captain Cone must surely be misinformed of the conditions in Italy. In a tightly spaced, six-page memo he detailed point and counterpoint of his actions and the Navy’s lack of cooperation, duplicity, and misrepresentation. “I need not point out,” he concluded, “that the Navy’s attitude in this matter was anything but fair and just.”

Eventually, the arrival of Maj. Robert Glendenning, La Guardia’s replacement, went a long way toward soothing Navy suspicions and restoring a healthy measure of inter-service amity. Though inexperienced, Glendenning proved “a much more satisfactory representative than the former.” Nonetheless, the war of memos and charges continued into early August, even after La Guardia relinquished his former duties. Callan sent a personal communication to Cone in Paris, including much of his correspondence with the Army representative, “together with memoranda I made on La Guardia’s answer.” In several places, Callan included underlines and special notes for emphasis, “In order that you may see for yourself exactly how he acted down here and know that he has not represented us in the proper manner or worked for the best interests of the service.” Under no circumstances, Callan declared, should the Navy deal with La Guardia. The New York congressman, it seems, had left everybody in the lurch, including his own replacement, and his actions in the final two weeks of his tenure “were absolutely intolerable.”

Unfortunately, belated cooperation between the Army and Navy did nothing to speed construction of critically needed Caproni bombers or remediate the severe defects that soon became apparent in the small number handed over to American forces. The decision to rely on Italy as the sole source of crucial aircraft proved to be a fatally flawed one from which the Northern Bombing Group never recovered.