Beginning with Irvin McDowell, the Union general who lost the First Battle of Bull Run (July 21, 1861), and continuing with George B. McClellan (“The Young Napoleon”), John Pope, Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker (“Fighting Joe”), and Henry Wager Halleck (“Old Brains”), the Union’s top generals were all West Point graduates and as highly qualified as it was possible to be in the nineteenth-century American military. Yet, to a man, they produced disappointing, often heartbreaking results on the field of battle. Even George Meade, under whose command the Army of the Potomac won the turning-point Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), let Lincoln and the Union down by failing to pursue the defeated Army of Northern Virginia in its withdrawal back to Confederate ground.

In contrast to varying degrees of failure in the Eastern Theater of the war, one general in the Western Theater was producing some remarkable results. He was Ulysses S. Grant.

For too long, hardly anybody paid attention. Halleck, his commanding officer in the Western Theater, was uncomfortable with Grant’s relentlessly aggressive spirit. Halleck favored a strategy of protecting territory over killing the enemy, disdained Grant’s personal appearance as insufficiently military, and was quick to give credence to unsubstantiated rumors of drunkenness. For his part and in contrast to Halleck, Grant was resolutely apolitical, which meant that he lacked the connections that advanced many other less-deserving officers.

But the most formidable obstacle to Grant’s advancement was the very theater in which he achieved his successes. All eyes were on the Eastern Theater, especially Virginia. What happened in the vicinity of the Mississippi typically elicited from public and politicians little more than a nod. The one exception was Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862). While that battle ended in an important strategic victory for the Union, opening up an advance into northern Mississippi, its cost in casualties was unprecedented: more than 13,000 Union soldiers killed, wounded, captured, or missing—about one in five of the men who fought. From among a horrified public came demands that the president fire Grant. To these Lincoln responded that he needed Grant, needed him because “he fights.” While the Northern press pointed to a 20 percent casualty rate among Union forces at Shiloh, Lincoln noted a nearly 26 percent rate among the Confederates. While the likes of McClellan and Halleck viewed strategy in the Napoleonic terms of controlling territory, Grant was killing the enemy army. Grant understood that the Union North not only possessed a stronger economy and much greater industrial capacity than the Confederate South, it also had many more people: 23 million versus 9 million in the South, of which 3.5 million were slaves. The North could make good its manpower losses. The South could not.

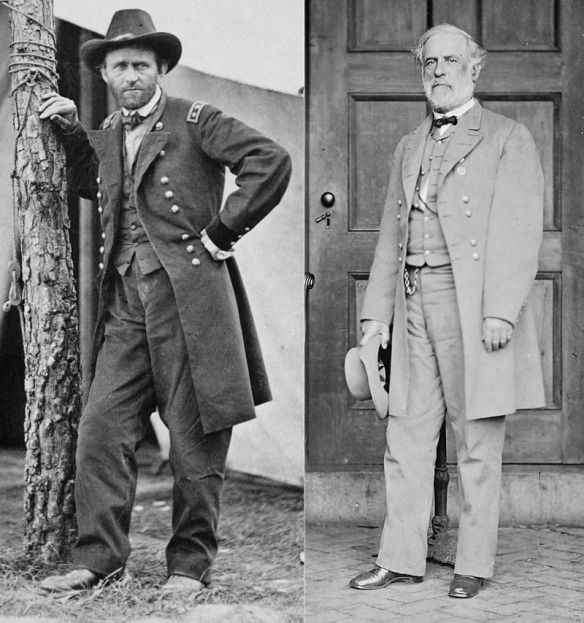

Still, it was not until March 9, 1864 that President Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general—making him the highest-ranking officer in the US Army—and then appointed him chief of all Union land forces. Up to this time, Lincoln had been replacing one general after another, vainly searching for the right combination of fighting spirit and strategic skill. In Grant, he finally found a military leader not with a little more of this or that, but with an entirely new approach to the war. Under Grant, the Union armies would have a single aim: destroy the Confederate armies. Yes, Grant would still attack major Southern cities, but less to simply occupy them than to deprive the Confederate army of its ability to furnish transportation and supplies. And, yes, he would resume the advance against Richmond, but less for the purpose of claiming the Confederate capital than with the objective of continually forcing Robert E. Lee to defend it and, in the process, sacrifice men he could not afford to lose.

By the time Grant was given the North’s top military job, only two major Confederate armies remained on the field: the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Robert E. Lee, and the Army of Tennessee, under the command of Joseph E. Johnston. Kill these two armies, and the war would end. Grant had on hand two major instruments of their destruction. The first was the Army of the Potomac, and the second the Military Division of the Mississippi.

Before becoming the Union’s general in chief, Grant held command of the Military Division of the Mississippi, having stepped up to the post from command the Army of the Tennessee. (Like most Union armies, it was named after the nearest river and is not to be confused with the Confederate Army of Tennessee, which, like most Confederate armies, was named after a state or region.) When he left to take command of the Division, William Tecumseh Sherman succeeded him as commanding general of the Army of the Tennessee. With Grant’s appointment to the top Union command, Sherman then ascended to command of the Military Division of the Mississippi, whose main field armies were the Army of the Tennessee, the Army of the Ohio, and the Army of the Cumberland.

Sherman was every bit as aggressive as Grant, and, like him, possessed a keen faculty for cutting to the very heart of a problem. While Grant would use the Army of the Potomac, nominally commanded by George Meade, for the march against Richmond—all the while forcing repeated combat on Lee—Sherman summed up his mission in a single sentence: “I was to go for Joe Johnston.” While Grant ate away at the Army of Northern Virginia, Sherman was to destroy the Army of Tennessee. As Grant fought his way toward Richmond, Sherman would follow the tracks of the Western and Atlantic Railroad to take Atlanta. Seizing this would deprive the Confederacy of its chief transportation hub, and it would certainly force Johnston to fight.

On May 4, 1864, Grant and Meade, with roughly 120,000 men of the Army of the Potomac, crossed the Rapidan River. This script had been followed before, early in the war, by George Brinton McClellan. Unlike him, however, Grant was not plagued by a morbid fear of being outnumbered. He had accurate intelligence, which told him that Lee could no longer field more than 65,000 men. A warrior at heart, Grant was confident in his ability to defeat Lee, whom he outnumbered nearly two to one. His intention, moreover, was to choose the battle ground. He wanted to force Lee into the open, to expose the Army of Northern Virginia and to give the Army of the Potomac vast room for maneuver and its artillery clear fields of fire. The superiority of Union artillery was one of the North’s great advantages over the military of the depleted Confederacy.

Grant, to be sure, was not McClellan. But Lee was still Lee—a superb tactician when he was at his best and, even more, a commander committed to ceding nothing. He immediately understood that Grant meant to manipulate him into a position that favored the Union. Lee refused to be pushed. With numerically inferior forces and confronted by an invading army, a conventional commander would have dug in to make a stand in a static defense. Lee instead went on the attack, hurling his outnumbered army against the approaching columns. He hit Grant not out in the open, where the Union commander wanted to fight and where his artillery could be brought to bear, but in the dense forest known locally as the “Wilderness.” It was not a virgin battlespace. Almost a year to the day earlier, Lee had dealt Joseph Hooker and the Army of the Potomac a massive defeat here at the conclusion of the Battle of Chancellorsville (Aril 30-May 6, 1863).

The tangled woods and undergrowth were allies for the outnumbered, outgunned Lee. Grant could not use his cavalry on this ground, and artillery was all but useless. The Confederate commander had enlisted nature itself to even the long odds against him as the fighting began on May 5. Grant turned over the tactical management of the battle to Meade. It was behavior typical of a humble and selfless commander. Noble—but, in this case, a mistake. The conventionally competent Meade was thoroughly out-generaled by Lee. Not that fighting in the Wilderness was easy for the Army of Northern Virginia. Confusion, in fact, gripped both sides, and while the combat on May 5 was horrific, it was also non-decisive, necessitating another day of battle.

On May 6, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet led his corps in an envelopment of Meade’s inadequately deployed troops. In a brilliant move, Longstreet drove one flank of the Army of the Potomac into the other, creating a potentially catastrophic situation that prompted Grant to belatedly usurp Meade’s command prerogative by ordering him to make a fighting retreat. Nothing, not even the commencement of an attack, is more intense and desperate than a fighting withdrawal. In this case, the musket fire was so fierce that the surrounding woods and brush soon caught flame. Within a short time, entire tracts of the Wilderness were engulfed, and it is believed that as many as two hundred men, both Confederate and Union, either perished in the flames or were asphyxiated by smoke during the hellish night of May 7–8.

The butcher’s bill for two days of battle was 17,666 killed, wounded, captured, or missing out of an engaged force of 101,895 soldiers in the Army of the Potomac—a 17 percent casualty rate that included the deaths of two generals, the wounding of two more, and the capture of another two. Less accurately recorded were Confederate losses, but it is estimated that out of 61,025 troops engaged, 11,125 were killed, wounded, missing, or captured. It was an 18 percent casualty rate, and it included three generals killed and four (among them Longstreet) wounded.

Grant, having lost more men than Lee, was forced to disengage from the battle. In this sense, he suffered defeat. But, in proportion to the number of men fielded, Lee fared even worse, yet he held his ground. It was not the way Grant wanted to begin his grand offensive. But it was also true that he could afford to lose men whereas Lee certainly could not. In any case, whether he should be judged defeated or marginally victorious, Grant behaved nothing like a beaten general. Instead of withdrawing, he advanced. Having disengaged from Lee, he side-stepped the position held by the Army of Northern Virginia and continued south to a courthouse at a Virginia crossroads town called Spotsylvania Court House. One of the roads crossing here led straight to Richmond. Far from avoiding further battle, Grant invited it—for all practical purposes demanded it. Win, lose, or draw, he intended to kill more of Lee’s army.

For his part, Lee saw that his men were in high spirits. For all the blood they had shed, they felt that they had won—as, by the raw numbers, they had. Anticipating Grant’s destination, Lee drove his army to beat him in Spotsylvania. Elements of Jeb Stuart’s Confederate cavalry and I Corps commanded by Richard H. Anderson (substituting for Longstreet, who was recovering from his wounds) clashed with the Army of the Potomac’s V Corps under Major General Gouverneur K. Warren on May 8. The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House began as a skirmish, but Lee intended to fight on this spot the showdown battle of the Civil War. His aim was to exact a toll on Grant so terrible that the Northern electorate would not return Lincoln to the White House in the General Election of November 1864. His Democratic opponent—most believed it would be none other than George B. McClellan—would favor an immediate negotiated end to the war. That was the best the Confederacy could hope for, and, as Lee saw it, it was worth spilling blood for now.

A determined Lee initiated some of the most desperate fighting in a war that had been far more desperate than anyone could have imagined. He saw this engagement as quite possibly the last chance for the Confederacy. As for Grant, he deliberately avoided the behavior of a conventional commander. Instead of taking a stand or withdrawing, he did what virtually no commander would do under heavy attack. He maneuvered, repeatedly shifting his main line to his own left while continually counterpunching Lee, continually probing for a weak spot in the enemy flank. Lee was having none of it. Observing the action closely, he was always able to cover any portion of his flank that became exposed. His troops worked furiously to dig out of the Virginia clay a hasty defense. In some places, this consisted of shallow but serviceable trenches. In others, it was no more than a collection of holes, each dug by an individual soldier for his own protection. Elsewhere, a few men scraped out rifle pits, larger “firing holes” capable of accommodating several men. From their cover, crude as it might be, the Confederates took a terrible toll—yet Grant continued to sidestep, each time threatening to come around on Lee’s exposed flank. And, each time, Lee was forced to extend an already undermanned defensive line. This meant more digging and more exhausting labor, while also spreading the entire line thinner and thinner.

The old rules of warfare, the Napoleonic rules, the rules taught at West Point by men like Old Brains Halleck dictated that whichever side could concentrate the most fire on the enemy would prevail. These old rules called for taking a stand and firing on the enemy until the enemy gave up. Grant broke those rules by combining attack with maneuver. He refused to simply mass against some particular point in Lee’s line. Instead, he attacked and then sidestepped, threatening Lee’s flank and thereby forcing him to keep extending his line, which thereby became thinner. Who would lose? The general whose line was the first to snap.

Grant needed to find an edge in this blood-soaked contest of endurance. He had earlier pressured Meade into installing Philip Sheridan to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac; however, Meade and Sheridan immediately came into conflict over the proper role of the cavalry. Sheridan wanted to use it offensively, as a means of conducting hit-and-run raids, whereas the conservative Meade insisted on reserving the cavalry mainly for traditional reconnaissance missions. Now locked in desperate combat at Spotsylvania Court House, Grant threw his weight behind Sheridan’s proposal to lead the 10,000-man Cavalry Corps in a breakout toward Richmond. When Meade objected, Grant simply overruled him. Stuart’s cavalry consisted of 4,500 troopers versus Sheridan’s 10,000. Grant believed that menacing Richmond would force the outnumbered Stuart to fight and to lose. When Stuart was beaten, a gap would open up in the lines around Richmond, and then Lee would have no choice but to break off the battle at Spotsylvania Court House, withdraw closer to the capital, and thereby allow an additional Union advance.

Sheridan considered the size of the Army of the Potomac Cavalry Corps to be a great asset, but he soon discovered that it was also a liability, since it made it impossible for him to mask its movement from Jeb Stuart’s prying eyes. Seeing the approach—riding four abreast, the Union cavalry column extended about thirteen miles—Stuart decided to ambush Sheridan at Yellow Tavern, an abandoned inn six miles north of Richmond. He deployed his troopers in strong defensive positions, and he motivated them by explaining that they—and they alone—were all that stood between Grant and the capital city of their Confederacy.

Sheridan’s men rode into the trap—though it was sprung only on the leading edge of the Union column. The Battle of Yellow Tavern (May 11, 1864) raged for three hours before Sheridan pulled back, but not before one of his troopers shot Jeb Stuart, who died two days later. As with the loss of Stonewall Jackson to friendly fire at the Battle of Chancellorsville a year earlier (wounded on May 2, he died on May 10, 1863), the death of Stuart was a blow from which there could be no recovery. Like Jackson, Stuart was irreplaceable.

In the meantime, Grant repeatedly struck at Lee’s flank, only to be repulsed each time. At last, however, he was convinced he had found a vulnerability. He ordered Major General Winfield Scott Hancock and 20,000 men to engage Ewell’s Corps. The Confederate general had deployed his line in a salient—entrenchments bulging toward the Union lines in a pattern that gave the rebels a 180-degree field of fire. To Hancock’s men, it resembled an upside-down “U,” which they called Mule Shoe. By the end of May 12, Mule Shoe would acquire a new name: Bloody Angle.

Hancock was one of the most admired officers in the Union army. At Gettysburg, he was among the most aggressive commanders, and, as Grant expected him to do on May 12, he pushed everything he had against Mule Shoe. Beginning well before dawn, at 4:30 in the morning, Hancock began punching through Ewell’s line, breaching several places by five. Ewell, however, was not one given to panic. He sent every man he could to plug the breaches and, before noon, had managed to halt Hancock’s advance.

At this point, the manner of the fighting changed. It was no longer something out of the industrial mid-nineteenth century—massed musket fire. It was primitive, hand-to-hand, the men fighting with fists or, grasping their muskets by the barrel, using the butt as a club. Grant’s own aide-de-camp, Horace Porter, reported seeing “opposing flags … thrust against each other, and muskets … fired with muzzle against muzzle.” He spoke of men ramming their swords and their bayonets “between the logs in the parapet which separated the combatants” blindly stabbing at the enemy. By day’s end, a torrential rain began, but the fighting continued. Even darkness, which usually brought an intermission in battle, did not stop what Porter called “the fierce contest, and the deadly strife did not cease till after midnight.”

Lee saw the Bloody Angle as the battle’s crisis and, ignoring the entreaties of his officers and men, rode down to it, intending to command its defense in person. The men at the front threatened to mutiny if Lee, so important to them, refused to withdraw. At length, he did. Inspired nevertheless, his soldiers finally managed to beat back Hancock’s assault, and thus the action at the Bloody Angle came to an end.

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House would not end until nine days later—and then inconclusively. As before, Grant refused to withdraw. As before, he would side-slip his men and edged them closer to Richmond. On May 11, he telegraphed the War Department in Washington that he had suffered heavy losses. Eventually, these would be tallied as 18,399 killed, wounded, captured, or missing—a casualty rate of nearly 18 percent. In raw numbers, Confederate losses were 12,687 killed, wounded, captured, or missing. But this was out of a strength half that of the Army of the Potomac and amounted to a casualty rate of 23 percent. Grant concluded his telegram by declaring, “I … propose to fight it out on this line, if it takes all summer.”

His next major move came on May 31. Mindful of what it had cost when Lee beat him to the crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, he was determined to reach the next crossroads, Cold Harbor, before him. Because it was a mere half-dozen miles northeast of Richmond, Grant was certain Lee would do battle here. Yet again, however, Lee outguessed his opponent. When Grant arrived at Cold Harbor, Lee was waiting for him. The battle commenced on May 31, reached its height on June 2, and then petered out through June 12. This time, it ended in a frank defeat for the Army of the Potomac, which suffered nearly 13,000 casualties (killed, wounded, captured, or missing) to about 5,300 for the Army of Northern Virginia. Grant responded to this truly terrible defeat by continuing his advance despite a renewed public outcry in the North for his removal. Under his command in the Overland Campaign, 50,000 Union soldiers had been killed, wounded, captured, or had simply gone missing. This was 41 percent of the force (continually replenished) with which he had begun the campaign. Lincoln agreed with the public, including those who called for Grant’s dismissal. These losses were indeed unthinkable. But then he pointed out that the losses among the Army of Northern Virginia amounted to 46 percent. The Army of the Potomac could be restored to its full strength. The Army of Northern Virginia could not. Robert E. Lee was losing the war.

And so Grant once again slipped his army out of Cold Harbor, doing so this time by night, and crossing the Chickahominy. Lee watched. Lee knew what it meant. Grant was continuing on to Richmond. The Confederate commander realized that, short of surrender, he had no choice but to fight again. He did not believe Grant would ever quit. His only hope was that the people of the North would elect a new president, come November, who would quit—right out from under their general. But, right now, under Lincoln, Grant would not turn back. He would fight again. There was no question about that, Lee knew. The only question Lee must have asked himself was whether the Army of Northern Virginia could possibly last to November.