The prestige of Roman arms was at an all-time low and the situation was made even worse by the fact that the power-hungry Roman generals everywhere rose in revolt against Gallienus (253–268), the son and co-emperor of Valerian. With prestige low and civil wars being fought, the enemies of Rome seized their opportunity and broke through the frontiers everywhere. In Gaul Postumus created a separatist Gallic Empire, which weakened Gallienus’ position even further and led to the development of separate military organizations in the different parts of the Empire. And this was not the only revolt Gallienus was facing. It was symptomatic of the situation that Gallienus had to grant Odaenathus, the Arab prince of Palmyra, the command of all loyal Roman forces in the east with the title Corrector Totius Orientis against the Roman forces of the usurping family of the Macriani in Asia, while his own forces engaged their main army.

Gallienus could not trust any native Roman with the command of an army against Roman usurpers, but his emergency measure led to further troubles. Its by-product was the short-lived Palmyran Empire, and one can say with very good reason that the father of the Palmyran Empire was Gallienus. Odaenathus’ role in the defeat of Shapur I in 260 and in subsequent events has been overstated. Odaenathus had merely raided Shapur’s personal retinue in 260 while the divisions of Shapur’s army were actually defeated by the Roman forces which consisted of those sent by Gallienus (the fleet under Ballista) and those who had survived the fall of Valerian. It was this army that the Macriani then turned against Gallienus.

In the West, the Dunkirk II marine transgression beginning in c.230 had led to the abandonment of the forts at the mouth of the Rhine, which the Franks had exploited by beginning to conduct piratical raids alongside their land operations. In 260 the Franks penetrated all the way to Spain before being defeated by Postumus, who then duly usurped power. The earliest recorded piratical raid of the Saxons occurred slightly later in the 280s, but it is possible that they too had started this activity earlier because a new set of fortifications was built on both sides of the Channel between c.250–285 that we today know with the name of the Saxon shore. The Roman coastal defences and fleets had proved incapable of protecting the coasts of Britain, Gaul and Spain.

Elsewhere, the Alamanni had been able to march into Italy before being defeated by Gallienus; the Goths and Heruls had ravaged Asia Minor, the Balkans and even the Mediterranean before being defeated through the combined efforts of three successive emperors – Gallienus, Claudius II and Aurelian; the Persians had ravaged Asia Minor and Syria; and the Berbers had raided Mauritania Tingitana. Similarly, further east other Berbers (Quinquegentanei, Bavares and Faraxen/Frexes) had ravaged the North-East of Mauritania Caesariensis and the North-West of Numidia from 254 to 259.

During Claudius II’s reign the Blemmyes had ravaged Egypt and the Marmaridae had ravaged Cyrenaica, and the Palmyran Arabs and their Roman auxiliaries had been able to conquer most of the east. Even the Isaurians had revolted and started raiding.

Gallienus did not only fight these enemies, but concluded treaties with the Franks, Marcomanni and Heruls. He was desperately short of manpower, and was therefore ready to use a combination of force and diplomacy. This policy allowed him to pacify whole sectors of the frontier and it also gave him access to a pool of auxiliaries and Foederati that he could employ against other foreign or domestic enemies. It was highly symptomatic of the situation that foreigners were needed for the fighting of civil wars.

However, eventually after many years of fighting, Gallienus managed to stabilize the situation partly thanks to the many reforms he made, partly thanks to his own superb generalship, partly thanks to the efforts of others (Postumus, Odaenathus, generals), partly by treaties, and partly thanks to the temporary abandonment of terrain to the enemy. Gallienus was faced with an unenviable situation, and therefore instituted many changes and reforms to save the situation: for example, he granted religious freedom to the Christians to gain their support, especially in the east.

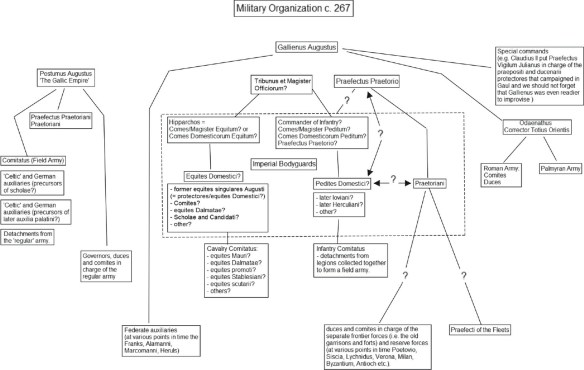

It should be stressed, however, that the reforms of Gallienus concerned only that part of the empire which was ruled by him. For example, in the Gallic Empire the usurper Postumus had to bolster his military strength by employing a great number of auxiliary troops consisting of ‘Celts’ (Germans or Gauls?) and Franks (SHA Gall. 7), who may have been the precursors of the Late Roman auxilia. In contrast, Gallienus created a personal field army comitatus consisting of a mix of new recruits and existing units and their detachments. The core of this army was based on cavalry that Gallienus grouped together. Foreigners did play a role in his army too, but mainly as allied forces.

The most famous of Gallienus’ reforms was the creation of the first separate mobile cavalry army, the Tagmata, in Milan as a rapid reaction force against threats from Gaul, Raetia and Illyria. The evacuation of the Agri Decumantes by Postumus opened Italy to invasions through Raetia. What was novel about the Tagmata was that the legionary cavalry forces had been separated from their mother units and joined together with the auxiliary cavalry units to form the first truly separate and permanent cavalry army (that is, it was not a temporary grouping) under its own commander. This army consisted of cavalry units/legions about 6,000 strong, the equivalent of infantry legions. But this was not the whole extent of the reform. Gallienus also separated the infantry units and detachments into their own separate 6,000-man ‘legions’. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that John Lydus (De magistratibus 1.46, p.70.3–4) also refers to the existence of separate 6,000-man infantry legions, and 6,000-man cavalry legions (i.e. the equivalent of later mere/meros) in the past, the practice of which I date to Gallienus’ reign.

According to the sixth-century author Lydus (De Magistr. 1.46), the professional Roman army consisted of units (speirai) of 300 aspidoforoi (shield-bearers185) called cohorts; cavalry alae (ilai) of 600 horsemen; vexillationes of 500 horsemen; turmae of 500 horsemen and legions of 6,000 footmen and the same numbers of horsemen. On the basis of the fact that this list fails to mention the limitanei or comitatenses and includes the praetoriani, it is clear that the names must predate the reign of Constantine. However, Lydus’ referral to the cohorts of 300 aspidoforoi should be seen as a referral to the use of the legions as phalanxes consisting of 320-man units. It is of course possible that this is a mistake resulting from his misunderstanding of the structure of the republican era manipular legion of principes, hastati, and triarii, which Marius had changed to include the light-armed velites for a total of 480 men. If Lydus is correct then the ‘cohort’ in question could be a second- to third-century detachment that consisted of only the four centuries of shield-bearers (à 80) for a total of 320 men (depth four to eight men), in addition to which came the light-armed (lanciarii, sagittarii, verutarii, funditores, ferentarii for a total of 160 men, deployed two to four deep). That is, with the inclusion of the light-armed this cohort retained the old strength of 480, but it was still smaller than the ‘old cohort’, because it had included in addition to the 480 legionaries 240 light-armed troops. This alternative receives support from the fact that the units would not have marched to war in their entirety, which would have made necessary the use of the abovementioned smaller cohorts. The other alternative is that we should identify the 300-man cohorts with the 256-man tagmata of the former legions mentioned by the Strategikon (12.B.8.1) so that each detachment (1024 men) consisted of four such and 256 light-armed men grouped separately. However, this seems to refer to the situation after the reforms of Constantine.

The creation of a separate independent cavalry Tagmata and commander (Aureolus in Zonaras 12.25: ‘archôn tês hippou’) can be seen as a precursor for the later division of the armed forces under a Magister Equitum and a Magister Peditum, as the title ‘Commander of the Cavalry’ also implies that there must have been a separate commander for Gallienus’ infantry forces. In fact, it is obvious that Gallienus’ infantry detachments, drawn from all over the Empire – including the areas under Postumus – required a new administrative system at the head of which must have been some commander for the infantry. It should be kept in mind, however, that on the basis of a papyrus dating from 302 the cavalry was not yet regarded as fully independent. That is, each legionary cavalry unit retained its connection with their infantry unit for administrative purposes until the reign of Diocletian (Parker, 1933, 188–9), but it is also possible that one of Gallienus’ successors reattached the cavalry back to the legions. Unfortunately, we do not know the title of the infantry commander that is likely to have existed for the infantry detachments. He may have been Comes or Magister Peditum, or Comes Domesticorum Peditum, or Praefectus Praetorio.

It is suggested that the Tribunus et Magister Officiorum was actually the overall commander of all Protectores, because according to Aurelius Victor 33, Claudius II, who was the most important man right after Gallienus in 268, had only the title of tribunus in 368. This would equate with the title of Tribunus et Magister Officiorum (note also SHA Elagab. 20.2). Gallienus was quite prepared to create large military commands for his trusted men. Of note is Gallienus’ creation of regional commands in the same manner as Philip the Arab had done. For example, the former ‘Hipparchos’ Aureolus served as Dux per Raetias in 267–268 with command of all of the forces facing Postumus and Alamanni in Italy and Raetia. The largest command was granted to Odaenathus who held the position of Corrector Totius Orientis, with the powers to command all of the forces of the East, but in this case Gallienus probably had little choice. It should be noted, however, that for the creation of the supreme command of the eastern armies there were also precedents, for example from the reign of Philip the Arab and even before that from the early Principate.

One of Gallienus’ more important reforms was the exclusion of senators from positions of military leadership (tribuni, duces, legati) in order to limit their possibility for usurpation. Obviously this did not concern every senator, only those who did not have Gallienus’ trust. Gallienus’ favourite senators still continued to hold on to and to receive new military appointments. Similarly, this exclusion did not concern the position of governorship. Gallienus’ reform meant that henceforth Roman generals would consist of duces (dukes), comites (counts) and praefecti (prefects), all appointed by the emperor, and no longer of the senatorial legates as before. Unsurprisingly, it was during this period that the senatorial legati stopped being commanders of legions. Henceforth the legions were commanded by professional military men of equestrian rank who had risen to higher commands through service in the ranks.

The dux (leader, duke) was originally a temporary command, but thanks to the fact that temporarily-created forces like Gallienus’ Comitatus and Tagmata were constantly operating together, the position became a regular one. Besides his command duties, the dux was also in charge of recruiting, training, and supply. The comes (companion, count) was originally a member of the emperor’s entourage, which now became a permanent title for a great variety of offices. Militarily the most important offices were the Comes Domesticorum (commander of the Protectores Domestici) and Comes rei Militaris (general). The inscription (PLRE 1 Marcianus 2) AE 1965, 114 Philippolis (Thrace) confirms the existence of comes or magister as military commander for the reign of Gallienus. It runs as follows: “ho diasêmotatos, protector tou aneikêtou despotou hêmôn Galliênou Se(bastou), tribounos praetôrianôn kai doux kai stratêlatês”. Dux and stratelates (comes or magister) are clearly two separate posts. The closeness of the comites to the emperor ensured better chances of promotion, just like with the protectores (see below). The importance of the temporary position of praepositus also increased and became semipermanent in many cases. The significance of the tribune also increased, the highest ranking of them being in charge of the units of bodyguards and the lesser in charge of the cavalry vexillations, legions and auxiliary cohorts.

Further, Gallienus increased the importance of the institutions of Protectores/Protectores Domestici (protectors/protectors at home/court), which may have been created by him or by Caracalla, and the Frumentarii (postmen/spies/assassins) as instruments of imperial security.

The exact status of the protectores/domestici is not known. There were also three or four types of protectores: those who had been posted in the provinces and whose origin probably lay in the governors’ bodyguards (equites and pedites singulares); those who stayed with the emperor and came to be called Protectores Domestici or Domestici (these latter were also later sent on missions as deputati); and those who had received the honour of simply being given the title. According to one view the protector was originally an honorary title that was then extended to men who acted as the emperor’s bodyguards/staff college from which the men received appointments to other higher positions, and/or the title was given to all officers who had reached a certain rank to make them more loyal to the emperor. According to this view the protectores were not really a military bodyguard unit, but simply men with the officers’ rank that acted simultaneously as the emperor’s bodyguards and staff-college and from which they could be seconded to special missions or for duty in the generals’ staffs.

According to another view there were two separate entities of protectores, the first of which was the staff-college/military intelligence staff and the second of which was an actual imperial bodyguard unit. According to this version, the latter protectores were formerly called either speculatores (300 ‘scouts’ stationed in the same camp as the Praetorians) or they consisted of the former equites singularis Augusti (c.2000 horsemen).

The suggestion is that there were ‘three’ bodyguard units of protectores/domestici: 1) the former speculatores who performed simultaneously the functions of bodyguards, military intelligence gathering, acted as sort of political commissars who kept their superiors in check, and acted as a staff-college for the emperor who could then use these officers for special missions; 2) military units like the equites singulares Augusti and Scholae/Aulici commanded by these protectores and which were also collectively called protectores; and 3) the former bodyguards of the governors and were now only renamed as protectores.

There are several reasons for this conclusion. The protectores were later used as commanders and officers of (for example) the Scholae of Constantine, which points to the likelihood that the protectores probably commanded different units under each different emperor. Many of these units would also have consisted of barbarians or other ethnic groups, just like the case with the equites singulares Augusti or Caracalla’s Leones. Consequently, during Gallienus’ reign the cavalry protectores probably consisted of the Equites Singulares Augusti, Scholae, Equites Dalmatae (and possibly also of the Comites, Equites Promoti and some other units) while its infantry counterparts would probably have been some palatine units like those later known as the Ioviani and Herculiani. Notably, the Equites Dalmatae formed Gallienus’ retinue at the time of his murder.

It is further important to note that besides being bodyguards, just like the praetorians and all those garrisoned at castra peregrinorum in Rome, the protectores were also used as spies and imperial assassins, and it is also known that Gallienus sometimes even spied upon people in person in disguise at night. As Frank has pointed out it is probable that the protectores also served as the military equivalent of the civilian agentes in rebus (successors of the Frumentarii) in the staffs of the period commanders. That is, the protectores performed military intelligence gathering missions which included spying on superiors and on foreigners. The messenger/inspector Frumentarii were by no means the only imperial special agents. It is not known whether Gallienus also used priests, astrologers and fortune tellers as informers just like the earlier emperors, but one may make the educated guess that such practices were also continued alongside the other systems.

Among the greatest successes of Gallienus can be counted that in his own portion of the Roman Empire he created and trained a highly efficient and mobile army commanded by equally gifted men of lowly Illyrian origin all of whom had risen through the ranks. It was this army and its leaders that breathed new life into the Roman Empire. It is true that the final mopping up of the Gothic and Herulian invading forces was left for Claudius and Aurelian (Aurelianus) to complete during the years 269–271, but it was still primarily thanks to the valiant efforts of Gallienus in 267–268 that the terrible migration/invasion of the Eastern Germans was stopped. The destruction of the Gothic and Herulian fleets, together with a sizable portion of their manpower and population, caused a temporary collapse of Gothic power in the Black Sea region with the result that, for example, the Sarmatians were able to regain control of the Bosporan kingdom. The same victory also secured to the Romans the control of the allied Greek cities of the North Black Sea such as Olbia and Chersonesus, the latter of which proved instrumental in warfare against the Bosporans. It is of course possible that the Romans never lost the control of these cities, but the crushing defeat of the Goths in 267–271 certainly secured these for the Romans. It is also probable that it was then at the latest that the ‘Huns’ moved westward to occupy lands north of the Caucasus previously under the control of the Goths, unless of course the reason for the Gothic invasions/migrations had not been their attack to begin with rather than the arrival of the plague with the lure of easy booty – additional details are included later in the narrative.

Despite all the frantic efforts of Gallienus, at the time when he was murdered by his own officers the Roman Empire was still effectively divided into three parts: 1) the Gallic Empire under the usurper/emperor Postumus; 2) the Roman Empire under the legitimate emperor Gallienus; and 3) the Palmyran Empire, still nominally ruled by Gallienus but already in practice by Zenobia, the widow of the murdered Odaenathus. The revolt of Aureolus and the murder of Gallienus had also meant that the mopping up of the Gothic invaders had been left unfinished, as a result of which Claudius’ short reign was entirely spent on dealing with the Goths, while the Palmyrenes rose in revolt against him. The Palmyrene takeover of the East and Egypt caused serious but not permanent damage to the classes Syriaca/Seleuca and Alexandriana both of which, however, appear to have managed to survive by fleeing to Roman territory. The end result of this was the resurgence of the problem of Isaurian piracy. The fleets as such survived and took part in the reconquest of the East during the reign of Aurelian.

Thanks to the fact that Gallienus’ almost only available recruiting area was Illyricum, he had brought the Illyrians to the dominant position among the military. The Illyrians were tough soldiers but only semi-civilized in Roman eyes. It was largely thanks to this that, after the murder of Gallienus by Illyrian officers, the Empire was effectively ruled by the ‘Illyrian Mafia’, at least until the downfall of the Constantinian Dynasty.