Fallujah was strategically important because the main Baghdad–Habbaniya road, 4 miles west of Fallujah, had been flooded over a stretch of 2 miles, presenting an impassable obstacle. The British needed, therefore, to approach Baghdad by way of Fallujah’s bridge over the Euphrates, a steel-girder structure of five spans’ width, 177 feet in length. The British troops assaulting it were divided into five small columns of about 100 each with supporting weapons, one being a section of RAF armoured cars and another including captured artillery. One was to move up along Hammond’s Bund, wading through the waters of the breach, three to cross the Sin al-Dhibban ferry with guns and armoured cars, the fifth to be landed by four Bombays and two Valentias at dawn in a position astride the road, to cover the main Fallujah–Baghdad artery with fire. This would seal all roads from Fallujah bar the track leading south-east to the Abu Ghuraib regulator, and this track was to be covered by a Kingcol troop of 25-pounders.

Once the columns were in position around Fallujah, air attacks commenced at 0500 on 19 May. During the day an RAF aircraft cut all telephone communications with the town, the crew landing, chopping down poles with hatchets and using wire clippers to cut the lines. Pamphlets calling for surrender were then dropped after an hour’s bombing, though they failed to induce the Iraqis to give up. Thus it was decided to try to capture the bridge using the column facing it from the west. The town was subjected to dive-bomb attacks, 134 sorties dropping 10 tons of bombs. The position was secured after it was bombed, machine-gunned and shelled by 25-pounders and the town was captured, together with 300 prisoners of war.

The British propaganda machine set to work immediately: ‘The rebel Iraq Army fled in disorder from Fallujah yesterday when they were attacked from three sides by British and loyal Arab troops,’ the British-controlled Basrah Times declared. ‘There were no British casualties. The inhabitants of Fallujah welcomed the troops and the restoration of law and order.’ ‘Things were beginning to look a lot more promising,’ wrote Freya Stark: at four o’clock on 20 May, news was received in the embassy compound that ‘Fallujah is taken, bridge, town and all. Thank God.’

But the Iraqis were not done yet. As the British cleared over 1,500 civilians from key parts of the town, on 22 May they launched a counterattack with the 6th Iraqi Brigade supported by Fiat tanks. Their main purpose was to blow the bridge to prevent the British advancing on the capital. Imperial forces in the town had been reduced since its capture and some intense combat followed, including house-to-house fighting, in which the King’s Own Royal Regiment suffered fifty casualties. A lorry containing gun cotton intended for the destruction of the bridge was hit and ‘blown to minute fragments’. The RAF Iraq Levies were to the fore in this engagement, with the role of the Assyrian soldiers particularly noted by their commander. D’Albiac told the British ambassador that the ‘determination of the Assyrians at FALLUJAH when a weak company defied an ‘Iraqi Brigade, supported by tanks, and one platoon counter-attacked and cleared the town when full of ‘Iraqi soldiers was one of the most important factors in breaking the morale of the ‘Iraqi army which certainly was broken at Fallujah’. The fighting had been hard. ‘In daylight,’ wrote de Chair, ‘the damage to the town, after consistent shelling by both sides, was an impressive sight and recalled pictures from youthful memory of the battered towns of Flanders in the Great War’.

Victory at Fallujah was a campaign turning point. Demonstrating the disconnect between German grand strategy and operations on the ground, it was not until the fourth week of the conflict that Hitler articulated his ambitions for Iraq. Directive 30, issued on 23 May, stated that:

The Arab Freedom Movement is, in the Middle East, our natural ally against England. In this context, the uprising in Iraq is of special importance. This strengthens the forces which are hostile to England in the Middle East, interrupts the British lines of communication, and ties down both English troops and English shipping space at the expense of other theatres of war. For these reasons I have decided to push the development of operations in the Middle East through the medium of going to the support of Iraq. Whether and in what way it may later be possible to wreck finally the English position between the Mediterranean and Persian Gulf, in conjunction with an offensive against the Suez Canal, is still in the lap of the gods.

The directive promised to help support the Iraqis with an air contingent, a military mission and arms deliveries. In addition, a German-led Arab Brigade would be formed using volunteers from Iraq, Syria, Palestine and Saudi Arabia. This was an extension of Sonderstab F (Special Staff F – ‘F’ standing for its commander, Hellmuth Felmy), a German–Arab unit for deployment in Iraq and elsewhere in the Arab world in conjunction with invading German armies, with a prospective strength of 6,000.

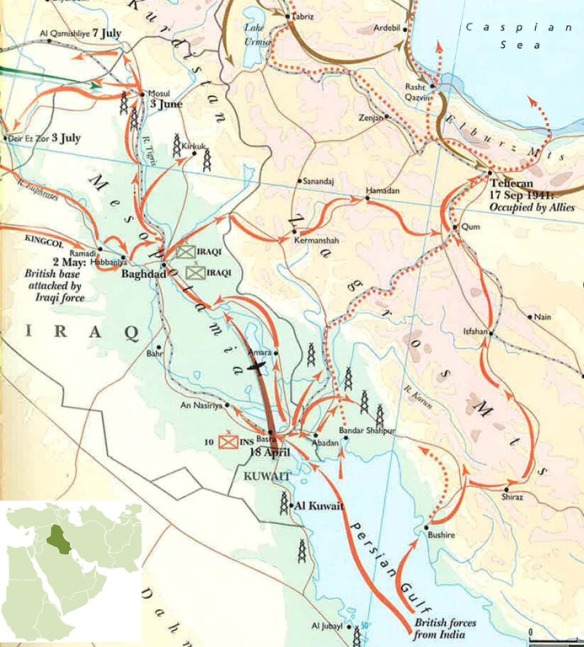

But ideas and plans for the future were one thing. What the Iraqis needed was immediate military assistance. The problem for the Germans was that they were too confident of eventual success in the war to invest properly in this operation. And, like the British, they were also hampered by distance, terrain and the demands upon resources. The Luftwaffe had strafed Fallujah on 23 May, but to little effect, and the Iraqis were mounting little more than nuisance raids and employing delaying tactics. On 21 and 22 May, for instance, they made an attempt, ‘frustrated by our patrols, to breach the bunds protecting Ashar [the business district of Basra] and Shuaiba aerodrome’. An operation on 25 May by a British battalion with Royal Navy and RAF support was successfully mounted against enemy troops 6 miles up the Tigris from Basra as efforts continued to push Iraqi forces back from the port. All of this ground activity was accompanied by ceaseless RAF sorties, recorded in the daily operational summaries. On 25 May Habbaniya-based aircraft flew 82 sorties, dropping 8 tons of bombs in the Ramadi area and bombing Mosul aerodrome. On the same day, 94 Squadron mounted standing patrols over Habbaniya and fighter escorts over Ramadi, and machine-gunned Iraqi vehicles discovered on the Baghdad road. Four enemy aircraft were machine-gunned at Mosul, and two of the five seen at Baqubah set on fire in a low attack. Habbaniya itself, meanwhile was bombed on that day by two Heinkel He 111s and three Messerschmitt Bf 110s. A successful attack on the Iraqi army and air force reserve petrol dump at Cassels Post destroyed a million gallons of fuel.

#

On 29 May Kingstone’s troops were engaging Iraqi positions in front of Baghdad.55 Fortunately, Iraqi opposition was only slight and by nightfall on 30 May the column had reached a point only 3 miles from the iron bridge over the Washash Channel on the outskirts of Baghdad West. It had been assisted by constant air reconnaissance and occasional close support bombing, and on 30 May very heavy bombing attacks with screaming bombs were launched on the Washash and Rashid camps, and on Iraqi troop positions in the vicinity of the Kadhimain railway station.

Air power remained a decisive factor. The RAF’s close air support had been vital in the campaign so far, and had had a devastating effect on morale as Iraqi resistance weakened. On 29 May there was some air combat and enemy transports north-west of Ramadi were machine-gunned, along with boats observed on Lake Habbaniya. On the following day RAF Habbaniya flew forty-two sorties, bombing troop concentrations and transports around Kadhimain in support of forward British formations on Baghdad’s outskirts. There was a mass leaflet drop over the capital, and a large fire was started at the motor transport depot at Rashid airbase. On 30 May Habbaniya’s aircrew flew twenty-nine sorties concentrating on a heavy bombing attack on Rashid and Washash, attacks made with screaming bombs ‘which proved most effective’, with aircraft of 94 Squadron escorting the bombers. 84 Squadron, meanwhile, performed reconnaissance flights over Ramadi, Hit, Mahmudiya, Musayyib and Karbala, and conducted a photo reconnaissance of Mosul and the K2 pumping station.

As British forces approached the capital, the rebel Iraqi regime disintegrated. With the city seemingly surrounded, Rashid Ali, the Grand Mufti, Grobba and the officers of the Golden Square scattered. It was left to the Mayor of Baghdad to sue for peace, and wireless sets were returned to the embassy. ‘After this,’ wrote Freya Stark, ‘in a sort of golden mist of sunset our bombers and fighters came sailing: they came in troops and societies, their outline sharp in the luminous sky: they separated and circled and dived, going vertically down at dreadful speed, like swordfish of the air’. A message was received at RAF Habbaniya from the British Embassy, just reconnected, requesting that an Iraqi flag of truce accompanied by an embassy representative should be received as soon as possible at the iron bridge. ‘As soon as we got this message,’ wrote Smart, ‘both the GOC [General Clark] and I decided to go ourselves to the Iron Bridge to meet the Iraqi Envoys’, the commanding officers keen to be in at the kill. A signal was sent to the ambassador fixing a time of 0400 on 31 May for the car with the flag of truce to be at the rendezvous. It was in this vehicle that de Chair entered the capital and pulled up at the embassy. Cornwallis, stirred from sleep, greeted him in his dressing gown and cummerbund, but he was soon kitted out in a white drill suit topped with solar topee and they were speeding back to the iron bridge.

The Mayor of Baghdad led the Iraqi delegation, accompanied by Cornwallis. In the cold light of dawn, the terms of the armistice were agreed. The Iraqi army was permitted to retain its weapons though was to return forthwith to its normal peacetime stations, and Ramadi was to be evacuated. All POWs and civilian internees were to be released, and all German and Italian personnel and equipment were to be detained by the Iraqi government. Fighting ceased at 0430, and the armistice was signed. Prince Regent Abdulillah and his entourage had already returned to Iraq in a procession of vehicles purchased in Palestine with the intention of drumming up support for his return to Baghdad, and were waiting in the wings at RAF Habbaniya, where the party was billeted in the Imperial Airways building that had been smashed up by the Iraqi army. Now, Abdulillah returned to Baghdad and resumed the regency. The Iraqi army was allowed to retire, ‘many of them deceived by their leader and not in fact disloyal’. This was a wise move, and made ensuing relations better than they might otherwise have been.

Knabesnhue reported on events to Washington. At 1430 on 30 May the Mayor of Baghdad ‘telephoned to inform me Rashid Ali and Axis group had left Iraq and that he headed a temporary Government to bring [the] conflict to an end’. He invited foreign diplomatic chiefs to his office. ‘I went first accompanied by Commandant Police to see the British Ambassador and thence with his Counsellor to the Mayor’s office.’ At the British Embassy, the armistice led to an ‘absolute orgy of activity all over the Chancery with typists flying in and out’. The embassy resembled ‘a railway station: officers from Habbaniya, colonels from Basra, Cawthorn from Cairo, Iraqis, people here leaving, cars scrunching, cawasses returning’. Members of the embassy community were told to wear their solar topees, presumably in an attempt to bolster British prestige rather than as a precaution against sunstroke.

Captain Sowerby of the 2nd Battalion the Essex Regiment, part of Habforce, had what he termed an ‘exciting night’ on the day the armistice was signed. In a letter to a friend he boasted that he ‘had had the satisfaction of being blooded in this war, though against the Iraqi rebels and not the Hun’. Arriving in Iraq his battalion had marched 50 miles in three days in full service marching order. ‘Then we had a few weeks of civilization and when the Iraqi show burst forth we were the first Company away and left barracks within an hour of receiving notice and were front line troops until after Rutbah and again later on . . . We had several scraps with very few casualties.’ On the eve of the armistice, Sowerby:

had to get a message to the Hq outside Baghdad, with the instructions for the reception of the envoys. I had two hours to do 25 miles of desert and 8 miles of flooded tarmac and then find the Hq which I was given to understand would probably be near the road and somewhere near Baghdad! Just as I got into the floods an outpost sentry told me that the road had been under heavy shell and MG fire all day, to cheer me up I suppose! I nearly overshot our front line but luckily spotted an Ambulance in time.

Finally locating the headquarters, Sowerby ‘panted in to the Brigadier’, Joe Kingstone, only to discover that his message had already been received as wireless communications had been re-established. ‘I managed to scrounge some tea though!’ he wrote.

Sowerby’s cheery tone reflected the fact that imperial ground forces had had a relatively easy campaign and suffered minimal losses. ‘For us it was but another campaign along the eastern marches of our Empire,’ wrote de Chair; ‘for them it was a war against the whole distracted might of Britain.’ British land and air forces had carried the day through resolute action, speed and deception. The armistice was finally forced by the small British contingent of approximately 1,400 men that had come from Habbaniya to Baghdad, with very little artillery or armour. As Freya Stark wrote, ‘we have done this with only two battalions’: the battle had been won by a ‘colossal bluff’.

#

Though Baghdad had been taken by legerdemain, the British had fought an excellent campaign and many factors accounted for the final result. The campaign’s most striking feature was the remarkable stand of the RAF’s No. 4 Flying Training School at Habbaniya. Using obsolete aircraft, a handful of experienced pilots and their inexperienced pupils lifted a siege by about 9,000 Iraqi troops, crippled German aircraft sent to the country and destroyed most Iraqi air assets before taking the fight to Baghdad via Fallujah. By holding out and then going over to the offensive, RAF Habbaniya bought crucial time for imperial relief forces from Palestine and India to concentrate and then deploy. In achieving this, Habbaniya was ably assisted by the air assets based at RAF Shaibah: the RAF had flown 1,600 sorties. Special forces had also played a role, with agents from the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and Special Operations Executive (SOE), and even Palestinian Jews recruited by SOE from the Irgun, undertaking sabotage missions: fuel dumps were targeted and sixteen newly arrived, American-built Northrop aircraft belonging to the Iraqi air force were destroyed on the ground. The Arab Legion played an unobtrusive but important role:

Glubb’s desert patrol was a talisman among the bedouin [sic], who would otherwise have molested our straggling supply column, thin-drawn out across the blinding desert, and have raided our solitary outposts along the route. In the event, we had no trouble from the tribes, who remained amicable with so many cousins under our flag, while the town dwellers of Iraq were loathing us with deadly passion.

To stand any chance of winning, the Iraqis needed to have eliminated the British at Habbaniya. As it was, though the airbase’s Assyrian and British churches were damaged along with messes and billets, the all-important water tower and power generator escaped unscathed and RAF aircraft never ceased using its runways for offensive purposes. Perhaps more importantly, if the Iraqis could have removed the British from Basra and blocked the Shatt al-Arab, they could have prevented British reinforcement by sea. Mahmood al-Durrah, a member of Rashid Ali’s government, ascribed defeat to a range of interconnected factors. The four members of the Golden Square, each in command of a major army unit or air force group, had pursued their own political ambitions and tribal interests. ‘As there was no overall command and control of Iraqi forces,’ he wrote, ‘their military fate was sealed.’ There was then the fact that no clear objectives had been provided to army group commanders except to be prepared to defend their regions. In contrast ‘the British had clear objectives that included securing Basra first and secondarily the airfield at Habbaniya’. There were other reasons for defeat, stemming in part from ministerial indecision at the beginning of May, which enabled the British to break out of Habbaniya before the Germans arrived. The Germans had warned Ali that they could not act to full effect before they had wound up their occupation of Crete and built up their air force and associated supply lines to Iraq. This indecision was caused by a split in the Iraqi ruling clique and also within the army. Essentially, the Iraqis went to war a month too early, and thus had to do without the German assistance that they were depending upon. Al-Durrah also highlighted the quality of British intelligence about the Iraqi forces, particularly as British officers had been employed in the army and air force as advisers and instructors until only weeks before fighting broke out.

A mordant critic of the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, Rashid Ali was later to write that he saw German battlefield success as a golden opportunity. ‘Believe me, I was ready for an alliance with the devil to get hold of the weapons I needed for the army to fight British troops.’ But he blamed failure on the lack of Axis support, and ‘bitterly concluded that as a puppet in Germany’s game he was not even of sufficient importance to receive her whole-hearted support’.