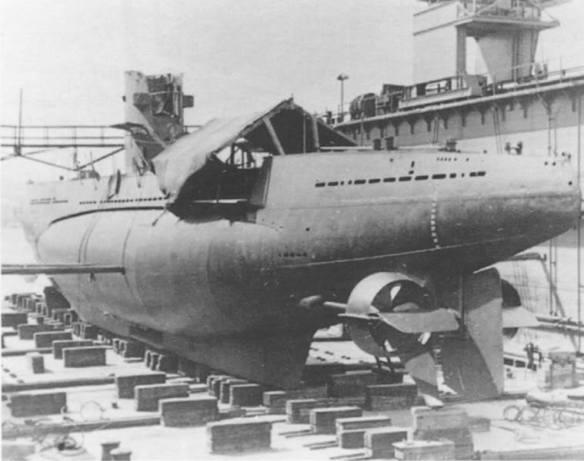

U-18 being re-assembled at Galați, Romania

Six U-boats were transported overland from Kiel on the Baltic to the Romanian Black Sea port of Constanta in 1942 to raid Russian shipping. Three were lost or scuttled in mid-1944, while the remainder were cut off from escape when Romania declared war on Germany in August 1944. They were scuttled in secret by their crews.

It was not until the middle of June that the 30th U-boat Flotilla was able to claim another confirmed success. Petersen’s U24 had sailed from Constanta to the waters between Tuapse and Cape Idokopas. There Petersen was ordered to attempt surprise attacks on towed convoys and coastal vessels proceeding under the lee of the coast, the aim being to force Soviet convoys to operate at night thereby restricting the effectiveness of escort vessels. Unsuccessfully bombed by two Soviet aircraft outbound, U24 reached its target area and attacked coastal freighters lying moored alongside jetties in the Mesib estuary, though the single G7e fired failed to detonate. Petersen opted to move on rather than potentially waste a second valuable torpedo. A pair of Il-2 ground-attack aircraft and an MBR-2 seaplane sighted U24 and attacked with nine bombs as U24 submerged – Soviet motor torpedo boats TK12 and TK32 and the patrol boat SKA062 later also detecting the boat on sonar and inflicted minor damage with twenty-eight depth charges. Finally, after avoiding what he believed to be a Q-ship, and missing an opportunity to attack a high-speed destroyer, Petersen torpedoed 441-ton minesweeper BTSC-411 Zashchitnik (No. 26), hitting the stern and sending the small ship under in ninety seconds after the hull fractured in two.

Two days later Petersen’s lookouts sighted what they believed to be U20, later discovering the boat to have been Russian as U20 was confirmed elsewhere. Determined not to make the same mistake again, U24 reported another submarine encounter to headquarters by short signal 28 miles south-west of Sukhum, shadowing while transmitting signals to U19, though the latter was too distant to attack. At 8.04 a.m. Petersen fired a single torpedo, but missed as he had underestimated the target speed: losing contact shortly thereafter. With a single torpedo left Petersen was ordered to close the Soviet coast and use it before returning to Constanta. Depth charged once again on 25 June off Tuapse, U24 reached Feodosia the following day to refuel before returning to Constanta without encountering any further enemy vessels.

U18 and U19 had both departed Constanta on 16 June, the former proceeding to the area north of Tuapse via the northern route that skirted the Crimean peninsula – the latter taking the southern route near Turkey to reach Batum. Fliege’s U18 sighted a surfaced Soviet submarine at 0.30 a.m. on 19 June, but struggled to obtain a firing position, dangerously silhouetted by the setting moon behind the boat. As the Russian submerged, Fliege was ordered to make a hydrophone search until 6.60 a.m., but could not regain contact.

On 20 June Luftwaffe reconnaissance reported a tanker convoy headed to Tuapse. U18 was ordered to engage but the message reached Fliege too late as he cruised submerged near the Soviet coastline during daylight. Three days later he sighted a convoy of two steamers, one motor minesweeper and an escort vessel, 20 miles south-east of Tuapse sailing south-east at moderate speed. Fliege fired two magnetic torpedoes but was unable to observe the result as retaliatory depth charges forced the boat deep. Two torpedo detonations were heard through the water as U18 slipped away. Two days later V.A. Gustav Kieseritzky (Admiral Black Sea since 28 February 1943) recorded that:

We have still not been able to establish the whereabouts of the steamer which U18 torpedoed on 23 June. At 0455hrs Luftwaffe reconnaissance sighted a convoy of two small freighters 5 miles west of Gagri and at 0529hrs another convoy consisting of a freighter of 1,000 tons, one motor minesweeper and one escort vessel between Ochomchiri and Poti; both course, southeast. According to dead reckoning, either convoy might be the one which had been attacked by U18. In the first case, the convoy would have sailed at a speed of 4.3 knots, allowing the torpedoed steamer to proceed at slow speed or in tow. In the latter case, the torpedoed steamer must have sunk and the remaining convoy’ would then have proceeded at 7.8 knots. At 0812hrs U18 contacted the first convoy again and reported the position to U24, However, either U24 did not receive the radiogram or defences prevented her from gaining an attacking position before the convoy put in to port, U18 was also unable to take the offensive, probably on account of the strong air patrols. At the end of the pursuit, both U-boats were ordered to new operational areas.

Fliege was credited by the Kriegsmarine for hitting and sinking the 1,783-ton steamer Leningrad, although this ship was still under repair in Batumi at that time after damage by the Luftwaffe. It is probable that the ship attacked was the steam tug Petrash which escaped unscathed, the torpedo detonation possible ‘end of run’ explosions.

Fliege moved on and attempted to torpedo a large tanker moored alongside the sunken floating dock at Sokhumi but was prevented by strong defences: U18 detected and subjected to four hours of depth charges. Fliege again managed to extricate his boat from the area and attempted to shadow tanker traffic heading south but lost contact. Finally, on 28 June, U18 reported sinking an unidentified lighter estimated at 1,000 tons with a spread of two torpedoes near Cape Pitsunda. Despite depth charge pursuit, Fliege escaped again. Low on diesel and ammunition he was ordered to the battered city of Sevastopol to take on fuel and torpedoes. It was the first time that the port was utilised by U-boats carrying out small repairs and replenishment rather than the trek back to Constanta, allowing the boat to return to the operational area for a further ten days.

Following a machinery overhaul, U18 was back at sea, escorted from harbour by R33 and R166 and bound once again for Tuapse. On 17 July U18 reported that it had torpedoed and sunk the 3,908-ton steamer Voroshilov travelling in convoy with two minesweepers, although it now appears that the target ship was actually Traktorist, missed by the attack. Depth charged as he slowly slipped away, Fliege first put into Feodosia to refuel before heading to Constanta, arriving on 20 July. In the shipyard a new Wintergarten was installed behind the conning tower with twin 20mm flak weapons. The increase in Soviet air activity was tangible and U-boats were increasingly attacked by heavily armoured fighter-bombers: aircraft becoming the primary threat as in the Atlantic battle itself thousands of miles away.

Although Fliege’s patrol had appeared the most effective thus far of the 30th U-boat Flotilla, he had sunk only a single patrol ship. The newly promoted Petersen’s U24 had achieved the most notable victory thus far on 30 July. After sailing on 24 July, Petersen had headed for the southern route to the coast off Sokhumi. U24 (Kaptlt Petersen) reported by radiogram at 8.40 p.m.:

Fired two torpedoes at a damaged tanker in Sokhumi. Depth charges. Tanker was 7,000 GRT, loaded or flooded, sea force 1, depth-setting 5.5 meters with magnetic firing pistol. Two hits were scored and the target broke apart. Three torpedoes left, 18m³ fuel, position air grid square 0326.

The third U-boat attempt to sink 7,886-ton Emba had been successful. The tanker had already absorbed much punishment: bombed and heavily damaged by Luftwaffe attack off Kamysh-Burun during January – the engine room was beyond repair. Towed to Sokhumi, and further damaged by mine while en route, she was anchored 300m from the coast and served as a fuel store. Emba was finally destroyed by Petersen after both U18 and U23 had failed in their attempts.

The redeployment of U24 that followed marked a shift in tactics used within the Black Sea. With little success enjoyed thus far, the tactical method of the U-boat group (famously called Wolfpacks) had been proposed by Admiral Kurt Fricke, (MGK Süd), although Kieseritzky (Admiral Black Sea) and Rosenbaum objected. A compromise was finally reached with attempts to form patrol lines rather than relying on lone-wolf sailings:

Appendix to War Diary of 6 August, 1943.

Copy: Admiral, Black Sea

To: Naval Group South, Sofia.

Copy to 30th U-Boat Flotilla, Constanta.

Subject ; U-boat pack tactics in the Black Sea

The suggestions made by Group South … for a new form of U-boat operations in the Black Sea have already been thoroughly examined here, but the attempt to develop pack tactics has been abandoned as a result of the commanders’ experiences in such operations.

Further considerations are as follows:

- Pack tactics were developed by the U-boat command in the Atlantic as an answer to the increased defences of the convoys there, when it became impossible for a single boat to attack. The idea was to dispose a concentration of boats against concentrated escort forces and massed targets. Half the boats would engage the escort forces and keep them busy, while the other half was able to attack.

- Conditions in the Black Sea area are totally different from the Atlantic. Here, there is no question of U-boat warfare in free sea areas against concentrated, strongly escorted targets. In the Black Sea we have a purely coastal war against coastal vessels which sail very close to the coast or against single, escorted freighters which are only encountered occasionally – at irregular intervals. In the Mediterranean where conditions have hitherto been similar, we do not use pack tactics. Admiral, Black Sea is planning a special form of joint operation, whereby several boats will form a mobile reconnaissance line with position lines parallel to the coast. Depending on the operational numbers, the boats will cover an area up to 12 miles from the coast. Thus they will harass stationary anti-submarine patrols by continuously altering position and at the same time will be free to operate against any targets within range reported by reconnaissance.

The three boats coordinated into Rosenbaum’s first attempt at a patrol line were U19, U23 and U24.

On the night of 6 August U19 began shadowing an escorted enemy tanker headed south-east near Sokhumi. In pursuit, the boat periodically lost contact, a Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft detailed to help regain the small convoy. Gaude was ordered to report the convoy’s presumed position so as to bring U24 into action. Petersen, having lost his Obersteuermann who had been taken ill aboard and transferred to a homebound U20, joined the hunt and shadowed the ships, unable to reach an attacking position before they disappeared, presumably into Sokhumi harbour. He received orders to penetrate the harbour and attack, the Luftwaffe once again involved in an effort to confirm the tanker’s presence. Shortly afterward Petersen spotted the tanker headed south once more towards Poti. With constant air cover, and lying too far astern of the ships, there was no chance for Petersen to haul ahead of the tanker and lie in wait – the chase abandoned and U24 returning to the patrol line near Tapir. By 11 August, U24 had sighted another Soviet convoy of towed lighters, but was sighted in turn, Russian patrol boat SKA0111 launching twenty-three depth charges that damaged U24. U19 was ordered to close the enemy ships but was unable to make contact. Shortly afterward Gaude reported that owing to a lack of potash cartridges and oxygen, U19 could only remain in the operational area until 14 August and Rosenbaum ordered the boat to Feodosia that evening, the patrol line held solely by U23 and U24:

It is regrettable that the effectiveness of this first attempt at a joint operation by three U-boats along the Caucasus coast should be reduced by this unexpected event, which leaves only two boats for the task. According to the last reports from these boats, they have enough fuel and ammunition and there was no mention of any scarcity of potash cartridges or oxygen. Both Command and the boats will have to learn from this experience.

The next day U24 also reported her oxygen supply depleted, compelled to head to Feodosia and leaving only U23 patrolling off Cape Pitsunda. The first joint U-boat operation within the Black Sea was officially abandoned while S-boat S26 sailed from Constanta carrying potash cartridges and oxygen bottles for the two U-boats.

A second attempt at combining the three was undertaken after U19 and U24 had resupplied. Starting at 3 a.m. on 20 August U19, U23 and U24 were to patrol for seventy-two hours in a single reconnaissance line close to the Caucasus coast between Lasarevskaya and Sochi. U19 and U23 were then ordered, on 25 August, to commence their return passages to Constanta in a reconnaissance line via the northern route to search for enemy submarines close to the Crimean coast and in the Cape Sarich/Constanta area.

Finally the tactic worked when Petersen intercepted and began shadowing two small 7-ton landing craft – DB36 and DB37, both empty apart from three-man crews – towed by patrol boat SKA0188. The landing craft’s shallow draught made them impractical to torpedo and so U24 surfaced at 1.24 a.m. and attacked the convoy with machine-gun and cannon fire. SKA0188 was claimed sunk by Petersen though the patrol boat returned fire, dropped the tow lines and escaped undamaged. Both landing craft were then left to U24, which approached them and attacked with gunfire and ten hand grenades after the 20mm jammed. DB36 was soon sinking in flames, all three crew captured, whereupon U24 concentrated on DB37, her crew surrendering. The vessel was sunk with demolition charges laid by two U-boat men that leapt aboard the damaged craft as the three prisoners were taken below decks on U24. Four of the six Russians had been wounded and Petersen sailed for Feodosia where they were put ashore as prisoners of war. Their interrogation revealed that the small convoy had been proceeding from Poti to Gholonjik in stages. Each landing craft – made from 5mm thick steel with a closed foredeck – was capable of carrying fifty men in full assault gear, reaching a speed of 6 knots under its own petrol-engine power. At least ten such vessels were known to have been shipped to Poti by railroad and planned for use in supplying the Myshako beachhead. From Feodosia, U24 then returned to Constanta.

Kapitänleutnant Wahlen’s U23 also sank an enemy vessel, the boat’s first Black Sea success. On 24 August at 8 p.m. Wahlen engaged the 35-ton former pilot boat and hydrographic vessel Shkval with gunfire, attempting to ram the Soviet ship as crewmen fired machine guns, cannon and threw hand grenades. With three Soviet crewmen killed the remaining seven abandoned ship in a lifeboat as Shkval sank in flames, helped on its way by demolition charges thrown aboard.

Wahlen could not repeat his success when ordered to join U18 in contact with a Soviet convoy near Pitsunda Point. Fliege had been driven away by searchlights and artillery fire as a Luftwaffe aircraft equipped with Lichtenstein radar on patrol near Kerch was diverted to help regain contact. Despite the electronic assistance, the enemy was not found. Wahlen sighted what he believed to be a 500-ton Soviet Q-ship at 1.50 p.m. on 25 August, stalking the target before firing three torpedoes, all of which missed as the U-boat was detected and attacked with seven depth charges. Wahlen later radioed his report to 30th U-boat Flotilla headquarters:

Presumably the Q-ship was the same ship as was encountered on the first enemy operation … stopped, now and then zigzagging to make smoke. Firing range 800 meters, angle of spread 4°, angle on the bow 90°, length of target 60 metres, torpedo ran 20 meters ahead of the bow. Clear location. Diesel engines. Accurate depth charges.

Following a rendezvous with U18 two days later, Wahlen observed three fast-moving minesweepers but was again unable to attack. On 2 September the boat docked at Feodosia, refuelling as Rosenbaum came aboard to greet the crew and talk with the young skipper. A week later, U23 was back in Constanta.

Fliege in U18 achieved some success during his patrol that had begun on 21 August: attacking what he recorded as an 800-ton Q-ship with a single torpedo on 29 August; the 400-ton minesweeping trawler TSC-11 Dzhalita hit under the aft mast and sinking within two minutes, stored depth charges detonating as she went down with fifteen out of the thirty-eight crew killed. The following day U18 attacked and damaged the 56-ton patrol boat SKA-0132 with gunfire near the coast at Ochamchire, forced to break off the attack when searchlights from shore dazzled the U-boat crew. The patrol boat was left burning as Fliege retreated to open water.

The U-boat was forced to make a detour to Feodosia to disembark an ill crewman – MaschMt Rolke – returning to action after also refuelling and reprovisioning. A final success was the reported torpedoing of an unidentified 800-ton vessel with one of two shots fired. Fliege observed the ship sinking through his periscope until depth charges from accompanying minesweepers forced Fliege to dive deeper.

Luftwaffe reconnaissance detected a destroyer with steam up, a 7,000-ton tanker, torpedo boat and several merchants in Tuapse harbour, drawing U18 to a position south of Tuapse boom to lie in wait for the tanker. At 9 a.m. Fliege attacked her as she sailed accompanied by a freighter, five torpedo boats and minesweepers with five circling aircraft overhead. Two TIII torpedoes were fired which missed all targets after which U18 was sighted, shelled and attacked with numerous depth charges: an ignominious end to the patrol that terminated at Constanta on 24 September. Nevertheless, on 8 October 1943, Fliege was awarded the German Cross in Gold.

Before Fliege reached the Romanian port he also discharged a single EMS mine into the water near Tuapse to counter the expected ASW hunt for him. The Einheitsmine Seehrohr Treibmine (EMS) ‘periscope drift mine’ was designed to resemble the periscope of a submerged U-boat. Laid from the deck of a surfaced boat, it floated for fifteen minutes before arming and automatically sank seventy-two hours later if unsuccessful. Allied escort vessels had a propensity for ramming submerged U-boats in an effort to destroy them and the 14kg warhead of the EMS mine would be triggered by contact with a ship’s hull and detonate. Later a different version of the EMS mine was developed that had no periscope but instead was topped by a plexiglass dome such as that used on the Neger and Marder human torpedoes. Marinegruppenkommando Süd had suggested that the mines be laid as U-boats departed their operational zones in the south-eastern Black Sea. The aim was twofold: to disable or destroy ASW ships and also to give the appearance of greater U-boat numbers. Soviet ASW forces would be divided as they hunted phantom boats that were in fact EMS mines, possibly even relaxing their search for genuine U-boats after the mines were discovered.

Kapitänleutnant Schmidt-Weichert’s U9 had also returned to action after repairs in Galati. Originally earmarked for minelaying operation, the unexpected breakdown of both U19 and U24 necessitated U9 mounting another torpedo patrol. Rosenbaum received instructions to instead prepare the next available boat, U20, for minelaying, a second special mission, the landing of agents behind enemy lines, also postponed due to a hold-up in the production of forged papers for the agents. Carrying a full torpedo load, and a single EMS mine, Schmidt-Weichert slipped from Constanta on 26 August at 1.38 p.m. under minesweeper escort, headed for the southern route towards Batum. Two days later U9 hunted three Soviet destroyers reported by a Bv138 flying boat, but failed to reach attack position, the submerged boat repeatedly ‘cutting under’, obscuring the periscope view. For this mission U9 had taken aboard a new LI as well as nine inexperienced new crewmen. Loaded with enough provisions to last thirty days, rather than the standard twenty-four, as well as carrying new equipment installations, U9 was heavier than normal and difficult to control for the new LI. At 1.50 p.m. Schmidt-Weichert attempted to attack a zigzagging destroyer but the boat dipped at the moment of firing, using an incorrect gyro-angle setting. The torpedo missed and the target was lost as it made off at high speed. Abandoning the pursuit, U9 resumed her march toward its operational zone. There, sailing between Batum, Poti and Sokhumi, U9 found nothing except air patrols which dropped bombs and brought ASW ships to the area to subject the submerged boat to depth charges, damaging hydrophones and the air search periscope. U9 managed to shake off its pursuit, later leaving behind an EMS mine with a two-day fuse running.

The boat suffered continual serious mechanical malfunctions, which forced a breakaway toward Sevastopol. By 4 September the hydrophones, navigation periscope and both compasses had broken down, the magnetic compass already malfunctioning after only two days at sea. Navigating by the stars, U9 sailed for the Crimean peninsula making accurate landfall on 6 September and escorted into Sevastopol by two Kriegsmarine artillery barges. Refuelling from the tanker Shell, U9 returned to Constanta in convoy with other ships, arriving as the Romanian harbour came under attack by Soviet torpedo aircraft. Four aerial torpedoes were launched, one of which hit the main mole causing damage and another fired at U9, but a ground runner that missed. The U-boat was hit by machine-gun fire and buffeted by bombing near misses, but suffered no appreciable damage as the U-boat crew returned fire with all available weapons. Four of the six attacking aircraft were brought down by the combined anti-aircraft defences within Constanta.

It was the end of Schmidt-Weichert’s tenure as part of the 30th U-boat Flotilla. He was transferred back to Germany for unspecified health reasons to take command of a company of the 1st UAA training unit, later posted to the staff of the 22nd U-boat Flotilla. In his stead as commander of U9 was ObltzS Heinrich Klapdor, previously IWO aboard U9 while it was still a training boat. The boat did not sail again until October, by which time the war in Russia had deteriorated once more.

On land, German forces were in retreat. February had seen the defeat at Stalingrad. During July and August the ambitious German offensive code-named Zitadelle, centred on cutting off and destroying huge Soviet forces in the Kursk salient, had failed. The last great strategic offensive that the Germans were capable of mounting on the Eastern Front ended following a titanic armoured battle that ultimately destroyed the backbone of the panzer forces. The military impetus now lay squarely with the Soviets who launched their own summer counter offensives.

As the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS was pushed west, the German foothold on the north-eastern Black Sea coast came under increasing pressure. On 5 May Soviet troops captured Krymsk, north-east of Novorossiysk, weeks later beginning an offensive against German units isolated between the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. By 7 September the battered 17th Army finally began to evacuate the Kuban bridgehead; on 27 September Temryuk fell to the Soviets and by 9 October the Kuban bridgehead had been destroyed. The final German and Romanian units evacuated to Crimea left the small island of Kosa Tuzla in the Kerch Strait at dawn that day. Although it could not be claimed a victory, the Kriegsmarine had successfully evacuated 97,941 tons of war material, 12,437 wounded, 6,329 soldiers, 12,383 civilians, 1,195 horses, 2,265 head of livestock, 260 motor vehicles, 770 horse-drawn vehicles and 82 guns between 7 September and the end of the withdrawal. Before long the Axis forces on the Crimean peninsula would be isolated as Soviet advances to the north cut off land access: now more than ever the land battles dependent on Kriegsmarine supply capabilities.