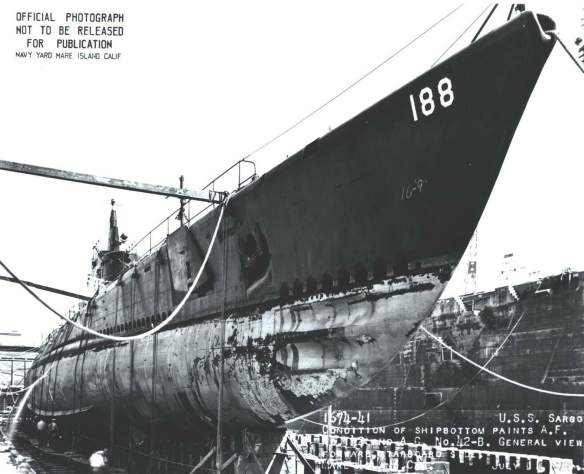

Condition of Sargo’s (SS-188) bottom prior to a paint job at the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, July 1941.

With much of the American Navy in tatters, with American airpower reduced to nearly nothing, and with American ground forces dying, retreating, or surrendering in droves throughout the Pacific, there seemed to be little hope for a major counteroffensive against the Japanese anytime soon.

The United States had but one force left in the Pacific capable of taking the fight to the enemy-the Submarine Force. Small though that force was-an army of ants trying to stop a stampeding herd of elephants- brave and sometimes foolhardy attempts were made by the submariners to interrupt Japan’s drive to dominate the Pacific.

During the remaining three weeks of December 1941, thirty-nine American submarines sailing from Pearl Harbor, Fremantle, and the Philippines conducted their first war patrols; fourteen went on their second; and one-Adrian Hurst’s Permit (SS-178)-went on its third. The results of the patrols were not just disappointing-they were downright appalling.

Swordfish in 1939

There were a few successes, however. Three Manila-based submarines did manage to draw blood. On 16 December, Chester C. Smith’s Swordfish (SS-193) sank a transport, while another enemy freighter was sent to the bottom by Wreford G. Chappie’s S-38 (SS-143) on 22 December; a third freighter was destroyed by Kenneth C. Hurd’s Seal (SS-183) the following day.

USS Swordfish underway off San Francisco, California, 13 June 1943

Seawolf underway off the Mare Island Navy Yard, California on 7 March 1943

Frederick B. Warder

During those final three weeks of December 1941 at least eleven other subs sighted targets, fired their torpedoes, but had no confirmed hits. 2 On 14 December 1941, Frederick B. Warder’s Seawolf (SS-197), normally based at Manila, slipped unnoticed into the harbor at Aparri, on the east coast of Luzon, where a small Japanese force had landed the day before. Seeing a seaplane tender at anchor, Warder fired a spread of four Mark XIV torpedoes armed with the new magnetic detonators-but there were no explosions. Somehow the torpedoes had either missed their targets entirely or their detonators failed to detonate. On his way out of the harbor, Warder fired four more torpedoes, but again, nothing. As Clay Blair notes, “Warder was furious. He had penetrated a harbor, fired eight precious torpedoes, achieved zero results.”

Sadly, most of the other American submarines had no better luck; their skippers’ patrol reports read like a laundry list of missed opportunities and heartbreaking failures. Near Formosa, Bill Wright’s Sturgeon, based in Fremantle, Australia, made a surface attack against a sitting duck cargo ship; all four torpedoes either missed or misfired. From Manila, Ted Aylward’s Searaven (SS-196) attacked two freighters, also near Formosa, without inflicting damage, while David Hurt, in Perch (SS- 176), with a good-size convoy in his sights, could not verify that any torpedoes struck home. Snapper (SS-185), under Hamilton “Ham” Stone, took on a cargo ship; it escaped unscathed. Pickerel (SS-177), with Barton E. Bacon Jr. at the helm, shot five torpedoes worth $10,000 apiece at a patrol boat; none hit it. Roland F. Pryce’s Spearfisb (SS-190) attacked an enemy submarine with four torpedoes, again without result.

Skipjack (SS-184), commanded by Charles L. Freeman, had a similar disappointing patrol. Spotting the choicest of targets-a big, fat Japanese aircraft carrier-Freeman closed in for the kill, fired three torpedoes, and got that sick feeling in his gut when none of them exploded. On Christmas day, Freeman tried again, this time at point-blank range against a heavy cruiser; as with the carrier, the target lived to fight another day. On New Year’s Eve 1941, Tarpon (SS-175), under Fewis Wallace, went after a light cruiser, but there was no New Year’s celebration because no hits were scored. After firing at least seventy torpedoes-$700,000 worth-Freeman and Wallace reported that in December they had sunk twenty-one enemy ships for a total of 120,400 tons. However, postwar records, compiled once access was gained to Japanese naval records, showed that only six ships, totaling 29,500 tons, were actually sunk. Not an auspicious beginning.

Even at this early stage of the war, and despite the many problems being encountered, legends of the submarine service were being created. One of the most unusual was that of the “red submarine.” When the Japanese struck Cavite Naval Base in the Philippines on 8 December, William E. “Pete” Ferrall’s Seadragon was undergoing an overhaul, including a complete repainting. There was no time to finish the paint job, so Seadragon set sail with just her red-lead undercoating showing.

The radio propagandist Tokyo Rose got wind of this unusual-color boat and soon was broadcasting to her listeners that America had a fleet of “Red Pirates” that were plundering Japanese shipping lanes; she promised that these criminal pirates would be executed when caught. Teaming of the broadcast, Ferrall’s men had a good laugh.

Although badly outnumbered, America’s antiquarian submarines were doing their best to make the Japanese warlords think twice before believing they had free rein in the Pacific. On 2 January 1942, Lieutenant Commander Edward C. Stephen of Grayback, sailing from Pearl Harbor, sank the 2,180-ton monster submarine 1-18 in the Solomons. On 24 January, as Japanese troops were preparing to land at Balikpapan, on Borneo’s southeast coast, a task force of four American destroyers and seven submarines, including William L. Wright’s Fremantle-based Sturgeon (SS-187), attacked and disrupted the amphibious operation, sinking four of the sixteen transports. Although the invasion was not halted, the damage done marked the first American naval “victory” of the war. It was small, it was insignificant, but it represented the tiniest glimmer of hope.

Hope would have been greater had the torpedoes been reliable. America’s submarines were armed with the latest Mark XIV steam-powered torpedoes equipped with Mark VI influence exploders. The failure of many torpedoes to detonate upon contact or within proximity of their targets was not the only problem; other torpedoes, for mysterious reasons, exploded prematurely, either just seconds after being launched or partway to the target.

Tyrell D. Jacobs, commander of the Manila-based Sargo (SS-188), experienced both vexations on one patrol. Encountering a large convoy near the major Japanese port at Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina (later Vietnam) on 14 December 1941, Jacobs launched a torpedo; it exploded eighteen seconds after leaving the firing tube and nearly wrecked the sub. On the twenty-fourth, Jacobs fired five torpedoes at three heavily laden transport ships north of Borneo without recording any hits. Three days later, Sargo went after two more freighters and a tanker; again, zero hits.

A total of thirteen torpedoes that had cost American taxpayers $130,000 had been fired on Sargo’s first war patrol, and not one of them had so much as knocked the paint off an enemy vessel. Sargo might as well have been firing spit wads for all the good they were doing. Jacobs had a well-trained crew, so he knew the chances for “operator error” were slight; it had to be the “tin fish” themselves. He analyzed the data, did the math, and concluded that the Mark XIVs were running ten feet deeper than their settings indicated and passing too far beneath the enemy hulls to set off the magnetic exploders. Jacobs compensated by instructing his torpedomen to set the depth shallower, but he knew he was only guessing at a solution.

A few days later, Jacobs spotted a slow-moving tanker, had one torpedo set to run at a depth of just ten feet, and fired. The gunnery officer, after calculating range and torpedo speed, stood by in the control room with his stopwatch, marking off the seconds until the torpedo, if it was working correctly, would detonate. At the moment he should have heard an explosion, there was only silence. Jacobs upped the periscope to see the tanker continuing on its merry way, oblivious to the fact that it had just escaped destruction.

Angry and frustrated, Jacobs reported the problem of the malfunctioning torpedoes to higher command; the torpedo problem soon would become a scandal of major proportions within the Navy.

It did the American war effort little good for submarine commanders to risk their boats and crews’ lives by traveling thousands of miles into enemy-controlled waters to locate a target, fire their torpedoes, and then watch in helpless frustration as the intended targets sailed away unharmed. But that is exactly what was happening, and on a large scale.

The number of ships sunk by American submarines in January 1942 was woefully insignificant. Of the six boats that sailed from Pearl Harbor that month, only three of them reported hitting anything-just four enemy vessels worth 23,200 tons. Pollack, commanded by Stan Mosely, sank a merchantman near Tokyo Bay on 5 January, and David C. White’s Plunger lived up to its name, sending a cargo ship plunging beneath the waves near Kii Suido on 18 January. Grenfell’s Gudgeon sank the enemy submarine 7-173, on 27 January in empire waters. Eight additional American subs departing their Australia and Java bases did little better, sinking but six ships during the entire month, for a total of only 23,000 tons.

The scarcity of sinkings was due not only to the unreliability of the torpedoes but also to their scarcity. Admiral Thomas Withers, Commander of Submarines, Pacific, or ComSubPac, criticized boat commanders who “wasted” torpedoes on targets. If a commander shot a second fish at a target that had been hit by the first one, Withers would dash off a withering note condemning the “profligate expenditure” of precious munitions. And, in January 1942, the torpedoes were precious-only 101 were in reserve at Pearl Harbor. Clay Blair notes, “According to prewar production schedules, [Withers] was to receive 192 more by July-about 36 a month. However, his quota had been recently cut to 24 a month. At the rate his boats were expending torpedoes, he would need more than 500 to reach July. There was no way the production rate could be drastically increased to meet this demand. Unless his skippers were more conservative, Pearl Harbor would soon run out of torpedoes.”

The submarine force, then, faced two equally important problems- a physical shortage of torpedoes and torpedoes that, when they were fired, rarely sank anything.

There are three main reasons why torpedoes might not sink their intended targets.

First, getting the torpedoes’ firing platform-the submarine-into firing position without being spotted and attacked by the enemy is not always easy. Second, the range is important; the closer the submarine is to the target, the more likely the chance of a hit. Conversely, the farther away, the less likely it is that the torpedo will strike home. Finally, a stationary target, obviously, is much easier to hit than a moving one. If the target is zigzagging or employing some other type of evasive maneuver, the chance of hitting it is even more remote.

In many instances, the submarine captain would fire a “spread” of torpedoes-usually three torpedoes fired within a few seconds of one another-in the hope that at least one of them would hit. And hitting a target presenting its broad flank to the submarine-and thus making for a larger target area-is preferable to trying to put a torpedo “down the throat” (a head-on shot at a target coming toward the submarine) or “up the skirt” (shooting at the rear of a ship as it is steaming away).

Setting the correct information into the torpedo’s guidance system is also critical. For best results, a torpedo should explode just beneath the centerline of a ship; the detonation will usually be enough to “break her back” and cause immediate sinking. If set to run too deeply, the torpedo will glide completely beneath the target’s hull; if set too shallow, it will strike just below the waterline and not cause enough damage to ensure a sinking.

What must never happen is that, after maneuvering carefully into a good firing position, taking steady aim, dialing the correct information into the torpedo, and firing at the proper moment, the torpedo itself malfunctions. Unfortunately, malfunctioning torpedoes were all too often a curse that plagued American submariners, especially during the first half of the war.

During the First World War, only one manufacturing facility made torpedoes for the United States Navy-the Alexandria Torpedo Station of Alexandria, Virginia. The armistice of 1918 had led to the closure of that station for, after all, the Great War was supposed to have been the “war to end all wars.” The Washington and London Naval Treaties also put a damper on torpedo development, for the nations of the world fully believed that it was possible to outlaw war and the tools of war. As history proved, their idealism could not have been more misplaced.

In the 1930s, with obvious signs that civilization was marching in lockstep toward a new world conflict, the U. S. Naval Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island, which had been established in 1869 as the Navy’s experimental station for torpedoes and torpedo equipment, explosives, and electrical equipment, went into the full-time manufacture of the underwater missiles; political wrangling delayed the reopening of the Alexandria facility until July 1941. In addition to these two, five more facilities-in Forest Park, Illinois; St. Louis, Missouri; Keyport, Washington; the Pontiac Division of General Motors in Michigan; and the International Harvester Corporation-received contracts to build torpedoes, not only for submarines but also for destroyers and aircraft. By the end of the war, over 57,000 torpedoes would be built. But the end of the war was a long way off. The torpedoes were needed now.

Even if there had been no torpedo shortage, the fact that the tin fish were so unreliable did not boost anyone’s confidence. Who in their right mind would want to sail into enemy-controlled waters and risk their boats and the lives of their crews with so little assurance that their torpedoes, once fired, would actually work?

And no matter how many submarine skippers sent in reports detailing the torpedo-detonation problem, there was no indication that anyone at ComSubPac or BuOrd or anywhere else was the slightest bit interested in acknowledging that a problem existed or that they wanted promptly to fix it. Just as maddeningly, the problem was intermittent; sometimes the torpedoes worked fine and sometimes they didn’t. How could anyone isolate a problem if the problems weren’t consistent?

The situation allowed innumerable enemy ships to escape destruction, and doubtless contributed to the prolongation of the war in the Pacific and the loss of many American lives.