It was the most important Italian bomber of World War II, this tough three-engined aircraft established a reputation that contrasted with most Italian weapons of the day, and it was flown with courage and skill. SM.79s served widely in the normal bombing role; but it is as a land-based torpedo bomber that the type deserves its place in military aviation history, being regarded by many as one of the finest torpedo bombers of the war.

The prototype appeared in late 1934 and subsequently had a varied career, setting records and winning races with various engines and painted in civil or military markings. The basic design continued the company’s tradition of mixed construction with steel tubes light alloy wood and fabric (this being the only way to produce in quantity with available skills and tools); but compared with other designs it had a much more highly loaded wing which demanded long airstrips,

The prototype SM.79 had flown on 2 September 1935, powered by three 750 hp AlfaRomeo 125 RC.34 engines, and so following the Regia Aeronautica’s preferred tri-motor formula. About 1,300 production models were built over a nine year period. They had internal provision for 2,750 lb (1,250 kg) of bombs, supplemented by under fuselage racks for a pair of heavy bombs, or two torpedoes in the case of the SM.79-II and SM.79-III.

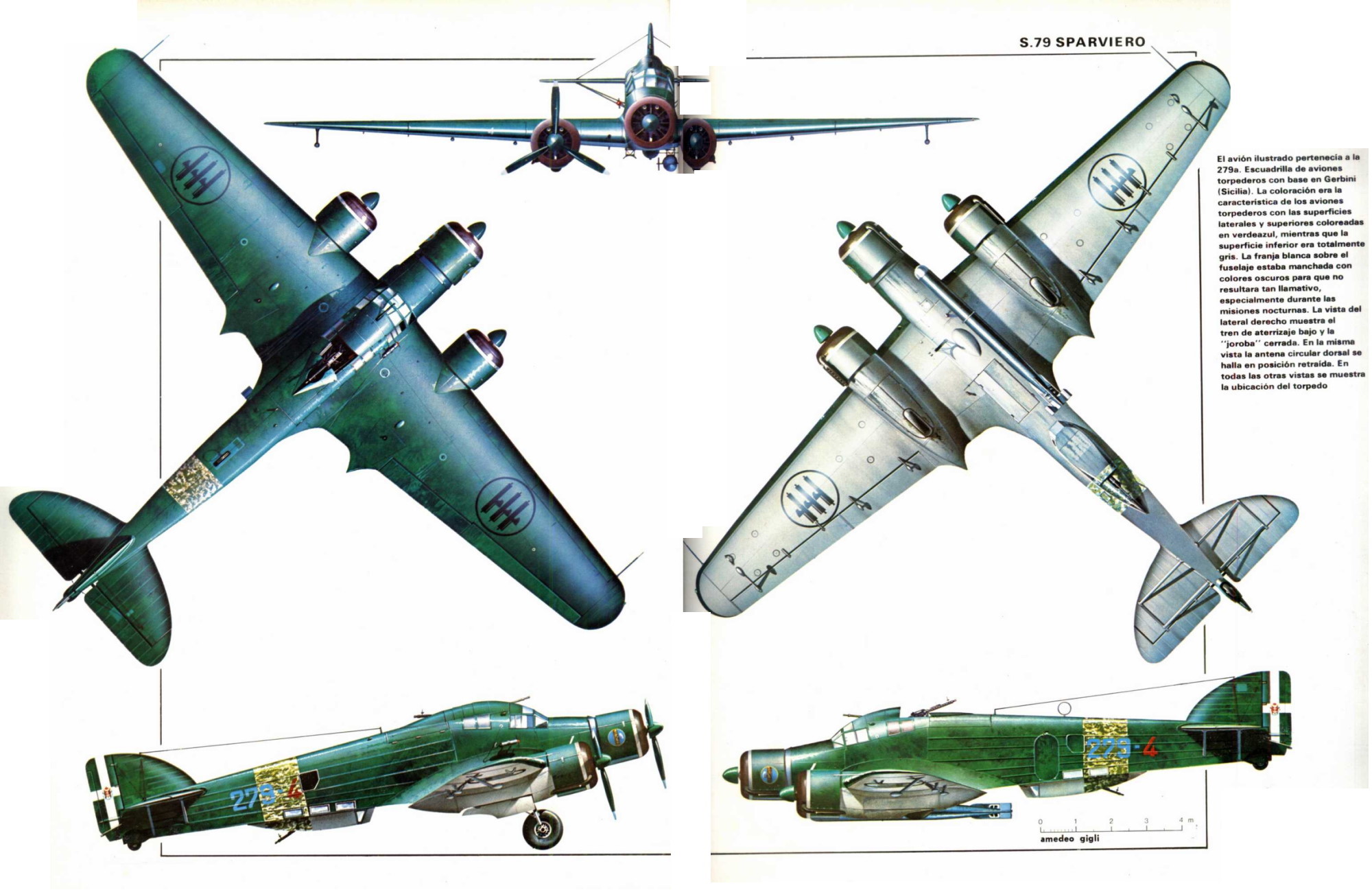

The SM.79 had a distinctive ‘hump’ on the upper forward fuselage, which housed both the fixed forward-firing heavy machine-gun and the dorsal gunner’s position. Its appearance earned the aircraft the nickname ‘Gobbo Maleditto’ (‘Damned Hunchback’). In spite of its cumbersome appearance and outdated steel tube/wood/fabric construction, the S.M.79 was a rugged, reliable multi-role medium bomber which did quite a bit of damage in the face of heavy opposition.

Developed from a civil airliner, the first Sparvieros entered service with the Regia Aeronautica in late 1936, just in time to fly combat over Spain with the Aviacion Legionaria, the Italian contingent fighting in support of the Nationalists. The SM.79-I established an excellent reputation in combat with the Aviacion Legionaria in Spain in 1936-1939. Its performance drew favourable comments from both sides, leading to a succession of export orders. The SM.79-I served with the Italian Aviazione Legionaria in support of Franco in the Spanish Civil War.

In October 1939 the Regia Aeronautica began to receive the 79-II with 745.2 kW (1,000 hp) Piaggio P.XI RC.40 engines (one batch had the Fiat A.80 of similar power) and this was the dominant version in action subsequently. About 1,200 served with the Regia Aeronautica including a handful of the III sub-type with forward-firing 20 mm cannon and no ventral gondola.

When Italy joined the war in 1940 its air force had nearly 1,000 bombers, of which well over half were Savoia-Marchetti S.M.79 Sparviero (Hawk) medium bombers. These trimotors, were thought by many to be among the best land-based torpedo bombers of the war. They could carry 1,250 kg (2,750 lb) of bombs internally or two torpedoes. Also active as a medium bomber around the Mediterranean and on anti-ship duties was the Cant Z.1007bis Alcione (Kingfisher) ,production of which began in 1939. It also was a trimotor, powered by 1,000 hp Piaggio radials, and it carried four machine guns for self-defence as well as up to 2,000 kg (4,410 lb) of bombs or two torpedoes.

In the summer of 1942, Allied efforts to relieve beleaguered Malta culminated in ‘Operation Pedestal’, when 14 merchantmen with heavy Royal Navy escort left Gibraltar on August 10. Among the enemy aircraft sent against them were 74 Sparvieri (Sparrow Hawks), a number of which had already scored hits on the battleship HMS Malaya and the carrier HMS Argus. ‘Pedestal’ eventually got through to Malta, but at the cost of one carrier, two cruisers, a destroyer and nine merchant ships, many of them having been hit by torpedoes from the S.M.79s.

The more powerful SM.79-II served in North Africa, the Balkans, and Mediterranean during the Second World War, while other units called Aerosiluranti (aerial torpedoes) pioneered use of these large fast bombers in the anti-shipping role. When the Italians surrendered on September 8,1943, it did not end the combat record of the SM.79, and a new version, the SM.79-III torpedo-bomber, was placed in production by the RSI, the fascist government in northern Italy.

An effective torpedo bomber as well, the S.M.79 served in the air forces of Brazil, Iraq, Yugoslavia, Romania and Spain, some right up to the end of the war. The Romanians flew them on the Russian front from 1941 to 1944, an unprecedented record for an aircraft designed in the early 1930s. Though known as a tri-motor, several versions were built as twin-engined aircraft using a number of different powerplants, including Junkers Jumo 211 D 1,220 hp inlines. Regardless of the version, its handling pleased most pilots and its ability to come home with extensive damage endeared it even more. Used throughout North Africa and the Mediterranean until the Italian surrender in September 1943, the Sparviero remained flying with both the Italian cobelligerent forces fighting alongside the Allies and the surviving pro-Nazi units.

About 100 were exported to Brazil Iraq and Romania – all of the twin-engined S.M. 79B variety. Romania built the 79JR under license with two 894 kW (1,200 hp) Junkers Jumo 211Da liquid-cooled engines. These were used in numbers on the Eastern Front; initially as bombers with visual aiming position in the nose and subsequently mainly as utility transports.

Post-war surviving SM.79s were converted into various versions of utility transports during the last phases of the war and survived in that role until 1952.

OPERATIONS

One area in which the Italian air force excelled was the torpedo-bomber. Although use of this plane was hindered by interservice rivalry before the war, the torpedo-bomber was deployed to units by late 1940. German air units later successfully emulated Italian torpedo-bombing tactics and purchased torpedoes from Italy. Yet the Italians chose simply to adapt a three-engine SM-79 level bomber for torpedo bombing rather than design a true torpedo-bomber.

1940

The Sparviero began its torpedo bomber (Aerosilurante in Italian) career on 25 July 1940 when a new unit was established after several years of experiments. The “Special Aerotorpedoes Unit” was led by Colonel Moioli. After having ordered the first 50 torpedoes from Whitehead Torpedo Works, on 10 August 1940 the first aircraft landed at T5 airfield, near Tobruk. Despite the lack of an aiming system and a specific doctrine for tactics, an attack on shipping in Alexandria was quickly organized. There had been experiments for many years but still, no service, no gear (except hardpoints) and no tactics were developed for the new speciality. This was despite previous Italian experiments into the practice of aerial torpedoing in 1914, 26 years earlier.

The first sortie under way on 15 August 1940 saw five SM.79s that had been modified and prepared for the task sent to El Adem airfield. Among their pilots were Buscaglia, Dequal and other pilots destined to become “aces.” The journey was made at an altitude of 1,500 m (4,920 ft) and after two hours, at 21:30, they arrived over Alexandria and began attacking ships, but unsuccessfully. The departure airport had only 1,000 m (3,280 ft) of runway for takeoff, so two of the fuel tanks were left empty to reduce weight, giving an endurance of five hours for a 4.33 hour journey. Only Buscaglia and Dequal returned, both aircraft damaged by anti-aircraft fire. Buscaglia landed on only one wheel, with some other damage. The other three SM.79s, attacking after the first two, were hindered by a fierce anti-aircraft defence and low clouds and returned to their base without releasing their torpedoes. However, all three ran out of fuel and were forced to jettison the torpedoes which exploded in the desert, and then force-landed three hours after the attack. Two crews were rescued later, but the third (Fusco’s) was still in Egypt when they force-landed. The crew set light to their aircraft the next morning, which alerted the British who then captured them. These failures were experienced within a combat radius of only about 650 km (400 mi), in clear contrast with the glamorous performances of the racer Sparvieros just a few years before.

Many missions followed, on 22–23 August (Alexandria), 26 August (against ships never found), and 27 August (Buscaglia against a cruiser). The special unit became known as the 278th Squadriglia, and from September 1940 carried out many shipping attacks, including on 4 September (when Buscaglia had his aircraft damaged by fighters) and 10 September, when Robone claimed a merchant ship sunk. On 17 September, after an unsuccessful day attack, Buscaglia and Robone returned at night, attacking the British ships that shelled Bardia. One torpedo hit HMS Kent, damaging the heavy cruiser to the extent that the ship remained under repair until September 1941. After almost a month of attacks, this was the first success officially acknowledged and proven. After almost a month of further attacks, a newcomer, Erasi, flew with Robone on 14 October 1940 against a British formation and hit HMS Liverpool, a modern cruiser that lost her bow and needed 13 months of repair. After several months, and despite the losses and the first unfortunate mission, the core of the 278th was still operating the same four aircraft. The last success of this squadron was at Souda Bay, Crete, when Buscaglia damaged another cruiser, HMS Glasgow, despite the anti-torpedo netting surrounding the ship, sending it out of commission for nine months while repairs were made. The aircraft continued in service until a British bomb struck them, setting off a torpedo and a “chain reaction” which destroyed them all.

1941

The year started out badly, but improved in April when many successes were recorded by SM.79s of the 281st and 280th . They sank two merchant ships, heavily damaged the British cruiser HMS Manchester (sending it out of service for nine months) and later also sank the F class destroyer HMS Fearless. However, one SM.79 was shot down 25 nmi (46 km) north west of Gozo on 3 June, landing in the sea and staying afloat for some time. Further Italian successes came in August, when the light cruiser HMS Phoebe was damaged. The large merchant ship SS Imperial Star (10,886 tonnes/12,000 tons) was sunk by an SM.79 in September. The 130th and 132nd Gruppi were also active during the autumn. On 24 October, they sank the Empire Pelican and Empire Defender, on 23 November they sank the Glenearn and Xhakdina, and on 11 December they heavily damaged the Jackal.

The year ended with a total of nine Allied ships sunk and several damaged. The Italians had lost fourteen torpedo bombers and sustained several damaged in action. This was the best year for the Italian torpedo bombers and also the year when the SM.84, the SM.79’s successor was introduced. Overall, these numbers meant little in the war, and almost no other results were recorded by Italian bombers. Horizontal bombing proved to be a failure and only dive bombers and torpedo-bombers achieved some results. The damaging of the British cruisers was the most important result, but without German help, the Italians would have been unable to maintain a presence in the Mediterranean theatre. The 25 Italian bomber wings were unable to trouble the British forces, as the Battle of Calabria demonstrated. Almost all of the major British ships lost were due to U-Boat attacks, with the damaging of HMS Warspite, and the sinking of HMS Barham and Ark Royal. The British fleet was left without major ships in their Mediterranean fleet leaving the Axis better situated to control the sea.

1942

The Axis’ fortunes started to decline steadily during 1942. Over 100 SM.79s were in service in different Italian torpedo squadrons. In addition to its wide-scale deployment in its intended bomber-torpedo bomber role, the Sparviero was also used for close support, reconnaissance and transport missions. In the first six months of 1942, all the Italo-German efforts to hit Allied ships had only resulted in the sinking of the merchant ship Thermopilae by an aircraft flown by Carlo Faggioni.

The Allies aimed to provide Malta with vital supplies and fuel through major convoy operations at all costs. Almost all Axis air potential was used against the first Allied convoy, Harpoon. 14 June saw the second torpedoing of Liverpool, by a 132nd Gruppo SM.79, putting it out of action for another 13 months. Regardless of where the torpedo struck, (amidships in the case of Liverpool, aft as for Kent, or forward as happened to Glasgow) the cruisers remained highly vulnerable to torpedoes, but no Italian air attack managed to hit them with more than one torpedo at once. On the same day the merchant ship Tanimbar was sunk by SM.79s of the 132nd, and finally the day after HMS Bedouin, a Tribal-class destroyer, already damaged by two Italian cruisers, was sunk by pilot M. Aichner, also of 132nd Gruppo. For years this victory was contested by the Italian Navy, who claimed to have sunk Bedouin with gunfire.

August saw heavy attacks on the 14 merchant ships and 44 major warships of the Operation Pedestal convoy, the second Allied attempt to resupply Malta past Axis bombers, minefields and U-boats. Nine of the merchant ships and four of the warships were sunk, and others were damaged, but only the destroyer HMS Foresight and the merchant ship MV Deucalion were sunk by Italian torpedo bombers. Although damaged, the tanker SS Ohio, a key part of the convoy, was towed into Grand Harbour to deliver the vital fuel on 15 August 1942 to enable Malta to continue functioning as an important Allied base, a major Allied strategic success.

By winter 1942, in contrast to Operation Torch, 9 December was a successful day when four SM.79s sank a Flower class corvette and a merchant ship, with the loss of one aircraft. Carlo Emanuele Buscaglia, another prominent member of the Italian torpedo-airforce who was credited with over 90,718 tonnes (100,000 tons) of enemy shipping sunk, was shot down the day after saying “We will probably all be dead before Christmas”. The risks of attempting to overcome the effective defences of allied ships were too great to expect much chance of long-term survival, but he was later rescued from the water, badly wounded.

Despite the increased activity in 1942, the results were considerably poorer than those of the previous year. The efforts made by the bombers were heavily criticized as being insufficient. Many debated the possibilities of torpedo manufacturing defects or even sabotage: the first 30 used in 1940 had excellent reliability, but a number of later torpedoes were found to be defective, especially those made at the Naples factory. During Operation Harpoon, over 100 torpedoes were launched with only three hitting their targets.

1943

The year opened with attacks against Allied shipping off North Africa, but still without much success. In July, the Allies invaded Sicily with an immense fleet. The Sparvieri were already obsolete and phased out of service in bomber Wings and its intended successors, the SM.84 and Z.1007, were a failure, while the latter were not produced in enough numbers. As a consequence, the latest version of the Sparviero was retained for torpedo attacks, being considerably faster than its predecessors.

Before the invasion, there was a large force of torpedo aircraft: 7 Gruppi (groups), 41, 89, 104, 108, 130, 131 and 132nd equipped with dozens of aircraft, but this was nevertheless an underpowered force. Except 104th, based around the Aegean Sea, the other six Gruppi comprised just 61 aircraft, with only 22 serviceable. Almost all the available machines were sent to the Raggruppamento Aerosiluranti. But, of the 44 aircraft, only a third were considered flight-worthy by 9 July 1943.

Production of new SM.79s continued to fall behind and up to the end of July only 37 SM.79s and 39 SM.84s were delivered. Despite the use of an improved engine, capable of a maximum speed of 475 km/h (295 mph), these machines were unable to cope with the difficult task of resisting the invasion. The size of these aircraft was too large to allow them to evade detection by enemy defences, and the need for large crews resulted in heavy human losses. In the first five days, SM.79s performed 57 missions at night time only and failed to achieve any results, with the loss of seven aircraft. Another three aircraft were lost on 16 July 1943 in a co-ordinated attack with German forces on HMS Indomitable. that was eventually hit and put out of combat for many months.

SM.79s were not equipped with radar, so the attacks had to be performed visually, hopefully aided by moonlight, while the Allies had ship-borne radar and interceptor aircraft. Despite their depleted state, the Regia Aeronautica attempted a strategic attack on Gibraltar on 19 July with 10 SM.79GAs, but only two managed to reach their target, again without achieving any result.

The last operation was in September 1943, and resulted in the damaging of the LST 417, on 7 September 1943. On 8 September, when the Armistice with Italy was announced, the Regia Aeronautica had no fewer than 61 SM.79s, of which 36 were operational.

Following the Armistice, the SM.79s based in southern Italy (34 altogether) were used by the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force as transports in support of the Allies; those that remained in the North (36) continued to fight along German forces as part of the Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana or were incorporated into the Luftwaffe. A small number of SM.79s remained in service in the post-war Aeronautica Militare, where they served as passenger transports into the early 1950s.

Specifications:

Savoia-Marchetti S.M.79 Sparviero

Dimensions:

Wing span: 69 ft 6 1/2 in (21.2 m)

Length: 53 ft 1 3/4 in (16.2m)

Height: 13 ft 5.5 in (4.1 m)

Weights:

Empty: 16,755 lb (7,600 kg)

Operational: 24,192 lb (11,300 kg)

Performance:

Maximum Speed: 270 mph (434 km/h)

Service Ceiling: 23,000 ft (7,000 m)

Range: 1,243 miles (2,000 km)

Powerplant:

Powered by three 559 kW (750 hp) Alfa-Romeo 126 RC.34 radials. Later three Piaggio P.XI RC40 1,000 hp 14-cylinder radial. The twin-engined S.M. 79B variety. Romania built the 79JR under license with two 894 kW (1,200 hp) Junkers Jumo 211Da liquid-cooled engines.

Armament:

It carried a 12.7 mm Breda-SAFAT gun firing ahead from the roof of the cockpit humpback that enabled bullets to clear the nose propeller; a second firing to the rear from the hump; a third aimed down and to the rear from the gondola under the rear fuselage; and often a 7.7 mm firing from each beam window. this needing a crew of at least five. The bombardier occupied the gondola with his legs projecting down in two retractable tubes during the bombing run. Up to 1,000 kg (2,205 lb) of bombs were carried in an internal bay; alternatively two 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedoes could be hung externally.