Swedish instructors in white tropical helmets (at left and right) training artillerymen of the Persian Gendarmerie.

In Viking times there were Scandinavian warriors, Varangians, in the Byzantine lifeguard. Since that time Swedes have served in many other foreign armed forces. They have done so for economic gain as well as for the sake of military experience, to escape boredom, and even some through forced enrollment. With the coming of the 1800s political ideas became an important factor.

From the tenth century until the thirteenth century warriors from the Scandinavian lands traveled to Miklagård, the Viking name for the Byzantine city of Constantinople, today’s Turkish Istanbul. They wanted to be Varangians and be enrolled into the prestigious Väringjalid (the Varangian guard). Scandinavians, with their exotic weapons, were seen as the best guarantee for the security of the Byzantine leadership. In Persia (Iran) between 1910 and 1920 and in Ethiopia and Spain during the 1930s, Swedes came to be seen with the same great trust and confidence as the Varangians had been. Before we report on the twentieth century Varangians, however, we need to give an overview of their predecessors during the previous three centuries.

Up to 1814, the last time Sweden as a nation was at war, Swedes in the armed forces of foreign states were not an unknown phenomena, but because Sweden’s own military was more active in that period, there were fewer Swedes who joined the military of other states. In those days it was necessary to occasionally resort to the enrollment of thousands of German, Scottish, Irish, and Swiss mercenaries to reinforce the Swedish Army. Paradoxically enough, even at this time, Swedish units could be hired out by the Swedish Regent to foreign princes during a lull in the Swedish campaigns!

A rather exotic example of a Swede who himself chose to serve in foreign uniform during Sweden’s Great Power epoch is Nils Matsson Kiöping, who in 1650 went into the service of the Persian Shah and took part in his campaign against Afghanistan.

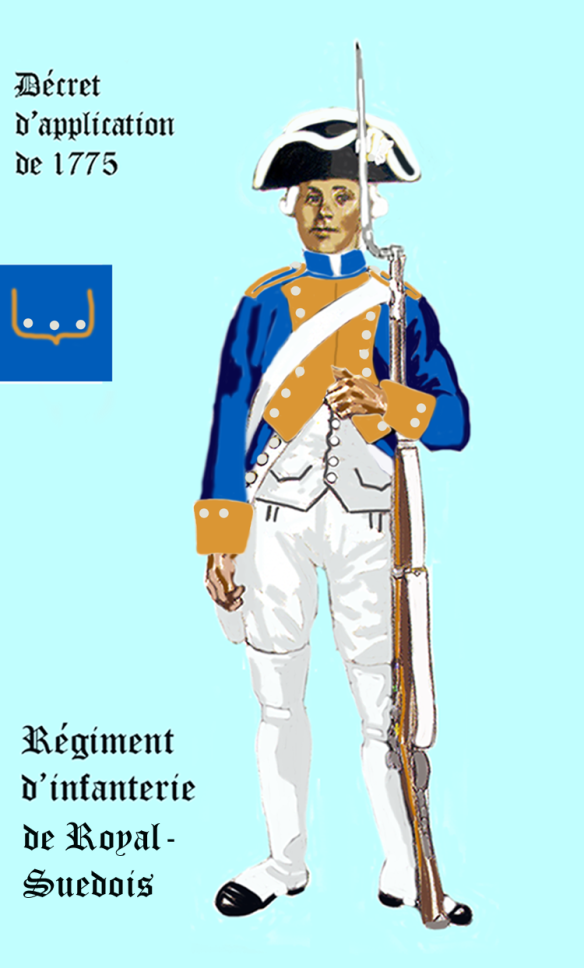

During the following century over 400 Swedish officers fought under the French flag. In the beginning they were mainly Swedish prisoners of war who in accordance with the custom of the time were offered to change prisoner status for war service. Later young Swedish officers came voluntarily to France to join a Swedish-led regiment there, that from 1742 was called “Royal Suédois” (Royal Swedish). At that time France led the world in military theory and the regiment also offered ample opportunities for practicing the art of war. Royal Suédois participated in the battle at Gibraltar in 1782, that strangely enough, was part of the American Revolutionary War.

Two Royal Suédois colonels were even more involved in the war that led to the foundation of the United States of America. Colonel Curt von Stedingk distinguished himself in close combat during the invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada in 1779. The Colonel and Count Axel von Fersen fought from 1780 to 1782 on the American side in the staff of French General de Rochambeau. The count then marched over 1,000 kilometers with the French forces in America. In October 1781 he took part in the capture of Yorktown. As General de Rochambeau’s personal interpreter he worked with General George Washington on three occasions. Today, however, he is more famous for his relationship with French Queen Marie Antoinette. Both von Fersen and von Stedingk were honored by General Washington himself with the hereditary Order of the Cincinnati.

Some 250 Swedish colleagues of the two colonels fought on the American side in French, Dutch, and local uniforms, to a great extent out of sympathy for the American rebels in their conflict with the British Empire.

Georg von Döbeln, future Swedish national hero, was also on his way to the American Revolutionary War, but the ship he sailed with changed its destination en route and sailed off to Asia. He thus had to content himself with fighting the British in India! During this same period at least 2,000 Swedes served as officers and crew within the Royal Navy of Britain and the British Merchant Fleet. It was not as a result of great sympathy for the politics of the British that led the Swedes to these ships, however, but rather the pay as well as professional interest.

The new category of Swedes in foreign war service—the ideologically motivated—appeared most clearly in the two Danish-German wars of 1848 to 1850 and 1864 when university students entered the battlefield under idealism’s banner. In the war fought from 1848 to 1850 some 260 Swedes fought on the side of Denmark. Barely half were career military. In the second phase of the clash, in 1864, almost twice as many Swedes served, and only one-fourth of them were military men. Not a single Swede is known to have fought on the German side in these wars.

During the Danish-German wars there was a craze for Scandinavia, called “Scandinavianism,” centered around Scandinavian history and unity. It was a deciding factor for many Swedes to sign up. This romantic idea of history is reflected very clearly in the medal that was struck in 1850 for former Swedish volunteers. It had a Viking motif on both the front and back side of the medal. In the second of the Danish-German wars the Swedish and Norwegian volunteers were assembled into a special unit called Strövkåren (Wandering corps). One of the Corps’ two companies was led by the future, very influential, Chief of the Swedish General Staff, Hugo Raab. A remnant of the strong Scandinavianist spirit of the mid-nineteenth century can be heard in the Swedish national Anthem words “I want to live, I want to die in Norden” (Norden being synonymous with the Nordic countries, that is, Scandinavia plus Finland and Iceland).

Even more Swedes participated in the Civil War in America. Over 3,500 served in the Union Army while several hundred were with the Confederates. These statistics, however, ought to be seen in the light of the fact that almost all were Swedish immigrants and many of them were offered rather impressive sums for enlistment. Forty Swedish officers, sergeants, and cadets did leave Sweden after the start of the war to join the military forces of the Northern States, though, among them a captain with the Dalarna Regiment, Ernst von Vegesack. He was much appreciated on the US side of the Atlantic and was made a brigadier general there (as was fellow Swede Charles Stohlbrand). After having become an American military hero at Antietam and Gettysburg, Ernst von Vegesack returned to Sweden and became chief of a military district.

The southern states also had two Swedish-American brigadier generals. Roger “Old Flintlock” Hanson was a Confederate brigadier of Swedish stock. Hanson commanded the 1st Kentucky Orphan Brigade and was mortally wounded on the last day of the battle of Stone’s River (Murfreesboro). Charles Dahlgren raised the 3d Brigade, Army of Mississippi, by his own means. When the war ended his slaves were taken from him and set free and he was not able to retain his plantation. Things went a lot better for his brother, Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, who chose to fight for the opposite side!

The total number of Swedes killed in action during the American Civil War is not known. Three of them are forever honored in Sweden, however, at the Military Academy Chapel in the Karlberg Castle, because they had completed training at that institution.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 attracted a group of Swedes to sign up for France. Their total number has not been ascertained, but they were perhaps a dozen or two. What is known about them is that several of them were veterans of the Danish-German war of 1864 and at least three of them were career officers. Only a single Swedish volunteer on the German (Prussian) side has been identified.

In the next war with Swedish participation there were two new phenomena which we rather associate with the epoch of the World Wars: concentration camps and commando troops. Both of these innovations saw the light of day not in Europe during WWII, but four decades earlier in South Africa. In the beginning of October 1899, immediately after the start of the so-called Boer War in South Africa between Great Britain and the two Boer Republics, a group of Scandinavian guest workers, seamen, and immigrants in Pretoria decided to organize a common free corps against the British. This initiative was led by a Swedish railway engineer, Christer Uggla. A total of 113 men joined, of which forty-five were Swedes, twenty-four Danes, eighteen Finns, thirteen Norwegians, and thirteen “others.” Johannes Flygare, the son of a missionary, was appointed captain of the unit. Even though he was a civilian, he had some war experience from the Zulu War. His deputy was First Lieutenant Erik Stålberg from Sundsvall, the only Swede on the Boer side with proper military leadership training—he was a Swedish first sergeant.

The Corps was organized like most Boer units; as mounted infantry. The Transvaal Government supplied ox-drawn baggage trains, provisions, weapons, and ammunition. The participants were promised citizenship and some form of payment in the event of victory. Lieutenant Stålberg got a week to teach the men the essentials of military life. The majority of the Scandinavians had no experience with weapons or even in horsemanship.

The Scandinavian Corps carried out sabotage against the railroad lines and on 24 October hastily moved to storm the fortified city of Mafeking, where the defense was led by Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, later the founder of the scout movement. The attack failed because of the lack of combat experience, and because of the machine guns of the British. Shortly thereafter, however, the Scandinavian volunteers were able to seize a British forward position outside the city, but they were unable to exploit this success.

At the end of November 1899 the Corps was sent to the south together with other Boer troops to stop a brigade of British elite troops—Scottish Regiments—on the way to relieve the besieged city of Kimberley. The Boers positioned themselves along the high ground called Magersfontein, to block the British advance. In the evening of 10 December most of the Scandinavians were placed a kilometer from the high ground in order to guard the main defensive force from a surprise attack. When the Boer General Piet Cronjé got information at three o’clock in the morning that the British were on the march directly towards his position, he ordered all his forward guard posts to be drawn back. The word did not reach the Scandinavians, however, and the result was a minor modern Thermopylae.

Despite an overwhelming superiority of forces and a monopoly on the machine guns it took the British several hours to take the Scandinavian position. There they found two who were not wounded, nineteen dead, and twenty-two wounded of whom a third were dying. In front of the Scandinavian position lay 279 dead and wounded British, mainly Scots. The British found it very hard to believe that the Scandinavians had so few men. In fact, they had had only seven more, who had succeeded in fighting through to the main position.

The remarkable stand of the Scandinavians was the result of an error. Had the order to retreat reached them they would presumably not have stood their ground, but this small battle contributed to stopping the British advance. That this did not change the outcome of the war was considered wholly unimportant, at least in Sweden. A hero cult arose around the Corps. The Swedish newspaper, Social-Demokraten, commented on the official Boer report about the Magersfontein front, “War is a calamity, wicked, but it would be foolish hypocrisy to not confess that we read with joy the lines…that deal with our Nordic countrymen.” Even The Times of London respectfully described the enemy Scandinavian Corps.

One of about ten Swedes on the other, that is, British, side during the Boer War was career officer Erland Mossberg. Completely in the spirit of the times it was Mossberg who took the initiative to erect a monument for the Scandinavian Corps—his former enemies—at the place where their greatest action took place.20 The Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet supported the project. A seven-meter-high granite Old Norse Memorial Stone (Menhir) was presented by a Finnish company and decorated with a runiform ornament, an engraved valkyrie. Four smaller stones were placed around the pillar. The names of the fallen are listed on the warrior shields. The stone stands there to this day, on the hill called Magersfontein.

The Boer War, with the Scandinavian Thermopylae as a climax, captivated the Swedes and the action blended an admiration for “Swedish war bravado” with a broad European enthusiasm for the Boers, an anti-British sentiment, and a sense of Nordic unity. But the most significant aspect of the Scandinavian Corps is that not a single Swedish professional officer (not even a former one) joined the Boers. The Corps was made up of Swedish civilians (albeit one a reserve officer) who were sympathetic towards Boer Nationalism. Moreover, Swedish women, for the first time, appeared in foreign war service. Three South African War Participant medals were given to Swedish nurses who belonged to the Scandinavian Ambulance. The ambulance followed the Scandinavian Corps and was virtually part of it. The ambulance personnel were not only fired upon, but also taken prisoner by the British.

The contrast between the Swedish officers in the Royal Suédois and the amateurs of the Scandinavian Corps is great, but both came to have successors during World War I and II.