GALLIPOLI 1915 Two Rolls-Royce cars of the Armoured Car Section of the Royal Naval Division, under Lieutenant Commander, Wedgwood, in the shelters dug to minimise the risks from shell fire.

Vice Admiral Carden received orders to begin his campaign against the defenses guarding the Dardanelles Straits on February 5, 1915. Churchill ordered two battalions of the Royal Marine Light Infantry—the Chatham and Plymouth Battalions—to join Carden’s fleet on February 6 for service ashore. The plan was for them to land and demolish any guns in the Turkish forts that the battleships could not.

An Admiralty memorandum was issued on February 15 that stressed the need for ground troops if the Royal Navy was unsuccessful. Thus, Kitchener agreed to make the army’s Twenty-Ninth Division available. This was the army’s only regular division not yet engaged on the western front, and his decision was a controversial one. Field Marshal Sir John French, commander in chief of the British army in France and Flanders (the British Expeditionary Force [BEF]), had been promised the division as a reinforcement, and he argued strenuously for it. His argument went unheeded, but he persisted, and on February 19 Kitchener reversed his decision. At the same meeting he suggested that the First Australian Division and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade should be sent to support the fleet instead.

On February 18 Churchill ordered the Royal Naval Division (RND) to the Aegean, and the French government dispatched a division of French and Colonial troops—to be called the Corps Expéditionaire d’Orient (CEO)—to assist. The divisions sailed for the Greek island of Lemnos, fifty miles from Gallipoli. There, what would become known as the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) established its forward base at Mudros, which has a natural harbor capable of handling a large number of ships. Two days later troops from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) that were training in Egypt were also ordered to Mudros. It was a surprise for them because they thought they were going to fight in France. Kitchener had no faith in the ability of either the RND or the “Anzacs,” as the Australians and New Zealanders were called. In fact, when Prime Minister Asquith asked him if he felt it would be wiser to use these colonial troops to support the navy instead of the Twenty-Ninth Division, he replied, “Quite good enough if a cruise in the Sea of Marmora was all that was contemplated.” The coming campaign would prove that his lack of faith was unwarranted. The Anzacs and naval infantrymen would be every bit as capable as the professional soldiers of the Twenty-Ninth.

The Royal Naval Division was an anomaly. It was Churchill’s brainchild. As first lord of the Admiralty, he found himself with more marines and reservist sailors than he had ships on which they could serve. So, he decided to turn them into infantrymen. The division consisted of twelve infantry battalions: four of Royal Marines and eight of men from the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, strengthened by stokers already serving in the navy and veterans recalled from the Royal Naval Reserve, who would serve as the battalions’ non-commissioned officers. The Royal Marine battalions were named after their home stations—Chatham, Deal, Plymouth, and Portsmouth. The RN battalions were named after admirals of the Napoleonic Wars—Anson, Benbow, Collingwood, Drake, Hawke, Hood, Howe, and Nelson. The battalions were supported by units of the Royal Marines—cyclists, medics, and engineers—but had no artillery directly assigned to them. Few of the men had seen action, and most of the sailors, having enlisted after the outbreak of war, had never even been to sea. Many had never even seen it. The division first saw action during the siege of Antwerp in October 1914, but far more men were captured by the Germans than were killed in combat. In fact, roughly half of the men in the division were taken prisoner and interned for the duration of the war. Those who made it out of Antwerp returned to England, and the division was hastily strengthened with new recruits.

The Landings of April 25, 1915—Helles

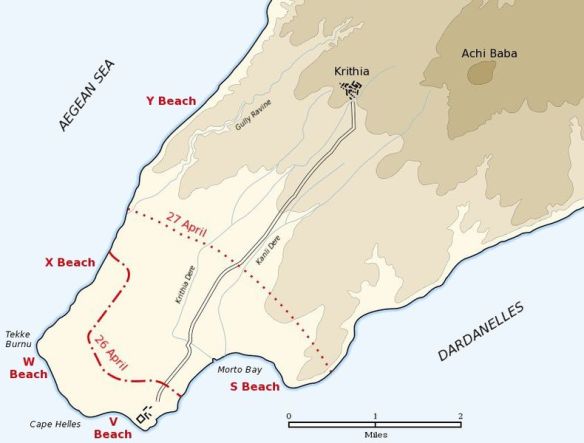

The landings at Helles were planned on a smaller scale than those at Anzac, but their combined objective was no less grand. The ultimate goal was the capture of a six hundred-foothigh hill called Achi Baba, north of the village of Krithia. As at Anzac, a covering force was to secure the ground ahead of the main landing areas, and the main body would advance through it to secure the hill.

The plan called for a covering force consisting of the British army’s Eighty-Sixth Brigade to land at the three beaches in the center of the landing area: V on the tip of the peninsula, W along the western edge, and X to the north of that. Two battalions and one company of the Eighty-Seventh Brigade, along with one battalion of Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI), were to capture Y (two miles north of X) and S Beaches (northeast of V). The Eighty-Eighth Brigade would then land at V Beach. With the covering force, it would advance north until its flanks linked up with the troops at Y Beach on its left and S Beach on its right. When this was accomplished, the other two battalions of the Eighty-Seventh Brigade would land at X Beach. After linking up with the two battalions from Y and S, they would move through the Eighty-Eighth Brigade to capture Achi Baba. The division’s only reserve was two infantry battalions that would land behind the covering force at X. In an effort to fool the Turks into thinking that a landing was also occurring on the other side of the peninsula, part of the Royal Naval Division (RND) would make a diversionary landing there, at a place called Bulair. The French would land at Kum Kale on the Asiatic side, both as a diversion and to keep Turkish troops there from reinforcing their troops on the peninsula. They also wanted to keep the mobile guns and the guns collectively referred to as “Asiatic Annie” from firing into the backs of the British landing at V Beach.

According to the plan, the landings would begin at five in the morning, and the area surrounding the beaches would be secured by eight. By noon the British would arrive at Krithia, and by evening Achi Baba would be theirs. This low hill, with its commanding view of the area, was important because as long as the Turks held it, they would be able to look down on the invaders and guide their artillery onto them.

This plan incorporated some major deficiencies. First, it allowed only for success; no consideration was given to the possibility of a delay at any of the beaches or that any of the landings might fail. Second, the planners did not believe that the Turks could mount a serious, coordinated defense. They did.

V Beach

While the assault on S Beach was a rapid success, V Beach was just the opposite. The defenders nearly drove the invaders back into the sea, and the Royal Navy did little to help the vulnerable infantry.

V Beach is a natural amphitheater. A cliff is on the right of the beach, high ground lies in front, and, perched on a rise to the right, is Fort Sedd-el-Bahr. The enemy covered the beach from this higher ground. The British knew it was heavily defended and that their only hope of success was to get a large number of men ashore quickly following a naval bombardment. For that reason Cdr. Edward Unwin, commanding officer of the communications yacht Hussar, made a novel suggestion. He proposed converting the collier River Clyde into a kind of Trojan horse in which troops could be moved quickly to shore. The idea was an ingenious one and would provide the necessary means for conveying a large number of men to the largest of the three main beaches. They could reinforce the first wave of a covering force, which would land before them from tows. According to Unwin’s plan, two large sally ports would be cut into either side of the ship, aft of the port and starboard bows. From these openings gangways lowered with ropes would provide the soldiers with their means of egress. Because the collier would ground a short distance from shore, a steam hopper called the Argyll would provide a bridge from the Clyde to the beach. This vessel was towed alongside the collier, and its momentum, once released, was meant to carry it to shore. As it glided forward, its crew of six Greeks, under the direction of Midshipman George Drewry and Seaman George Samson, would steer it in front of the Clyde. Once there, the gangways would be dropped, and the twenty-one hundred soldiers inside would rush across the Argyll and onto the beach. In the event Unwin’s calculations were off, he arranged for the Argyll to tow three modified rowboats to make up for any gap between ship and shore. He seemed to have thought of everything.

Among the units that landed at V Beach was the First Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. Half of the men of W Company were detailed to land at the Camber, a piece of dead ground below Sedd-el-Bahr Village, directly across the peninsula to the east. Their goal was to capture the village. At V Beach proper the first wave consisted of three companies of the First Dublins, along with fifty men of the Royal Naval Division’s Anson Battalion. These two groups would land first, from five tows pulled toward shore by the minesweeper Clacton. Each tow consisted of four rowboats pulled by a steam pinnace, each rowboat manned by a midshipman and six sailors from the battleship Cornwallis. After this group landed, the Clyde would be grounded and its troops landed. The soldiers would be covered by eight Maxim machine guns operated by men of No. 3 Squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service’s Armoured Car Division, who were stationed around the collier’s bridge. On board were the other half of W Company and the entire First Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers. The Dublins, along with Z Company of the Munsters, were to help the Dublins who landed at the Camber take Sedd-el-Bahr Village. They would then move on to take Hill 114, which stands behind the village and had a small fort and barracks on top. These men would exit the Clyde from the starboard (right) side, which would face the village. X Company of the First Munsters would exit from the port side. They were to take Fort No. 1, which stood atop the cliffs to the left of the beach and had been destroyed in the earlier naval bombardments. The Munsters’ other two companies, W and Y, were to remain in reserve. Also in reserve were two companies of the Second Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment and the 1/1st West Riding Field Company of the Royal Engineers. No. 13 Platoon of the Anson Battalion was to carry stores to shore once a successful landing had been made. Medical treatment would be provided by men of the Royal Army Medical Corps’s Eighty-Ninth (1/1st Highland) Field Ambulance.

The troops destined for V Beach began their journey to Gallipoli on the afternoon of April 23, when they moved to Tenedos. They were tense and displayed none of the joviality that some of the others felt as they departed for their meeting with destiny: “We left [Mudros] at 5.30 p.m. on April 23rd for the great adventure … A perfect evening, as we steamed stealthily out on H.M. [sic], H.M.T. ‘CALEDONIA,’ an incident memorable for its solemnity and one might say grandeur. Men-of-war, transports and ships of every sort ‘Dressed Ships.’ All the crews cheering us on our way, and those with bands playing us a farewell … What struck me most forcibly was the demeanour of our own men, from whom, not a sound, and this from the light-hearted, devil may care men from the South of Ireland. Even they were filled with a sense of something impending which was quite beyond their ken.”

The next day the Dublins and Ansons who would land in the open boats transferred to the Clacton, and those who would land on the Clyde boarded it. Early on the morning of the twenty-fifth the Ansons and Dublins were awoken and given a hot meal, then they climbed down the rope ladders and into the rowboats tied to the sides of the pinnaces. The sailors from the Cornwallis were already onboard, having spent a cold night sleeping in their boats. The men on the Clyde were also awoken and given a cup of hot cocoa before the vessels sailed for Gallipoli.

The rowboats were supposed to land first, following an hour-long bombardment by the battleship Albion. The pinnaces towing the rowboats met with the same problem as those that landed at S Beach: a stronger-than-expected current. They did not arrive until after 6:30 a.m., so the Albion continued firing on the area behind the beach. And there was another problem. At 6:10 a.m. the Clyde, which should have grounded after the tows had landed, found itself far ahead of them. Unwin thus decided to circle the Argyll in an effort to follow the original plan. In doing so, the khaki-painted vessel lost some of the momentum necessary to propel it forward to form the bridge. The collier grounded at 6:22 a.m. without so much as a jolt, eight minutes before the rowboats arrived. But it grounded much farther out than Unwin had planned—one hundred yards—and the Argyll beached fifteen yards away, too far to be of any use. The men onboard waited anxiously for the first wave to land.

The pinnaces cast off their boats fifty yards from shore, and the starboard tow headed for the Camber. As the remaining tows neared shore, Albion shifted its fire farther inland to avoid hitting the infantrymen. It ceased firing before they landed. The Turks, who had deserted their positions when the bombardment began, filed back to their trenches, unseen, and held their fire until they saw the boats cast off. Most of their positions did not appear on British maps and were so well concealed that Albion’s observers missed them. The two forts, which had been partially destroyed in the March bombardments, provided excellent cover for some of the defenders. The thick barbed wire—there were three strong belts in front of the trenches—was also visible. Yet Albion was stationed too far out to sea—approximately 1,450 yards—to be able to target the defenses accurately. When it did fire, its gunners were further hampered by the smoke and debris thrown up by the explosions. They were firing blind but managed to knock out two of the Turks’ four pom-poms. Unfortunately, the barbed wire was largely untouched, and the Ottomans were anything but demoralized by the bombardment. The damage was slight, and the invaders would pay for it with their lives.

When the pinnaces released their boats, all hell broke loose: “At this moment the Turks, whom everyone had thought were dazed and routed by the preceding naval bombardment, opened fire with everything they had, the range was short—something like one hundred yards frontally and up to three hundred yards on the flanks—for the cove where the landing was taking place was roughly bow shaped and quite small.”18 The Turks opened fire on the boats and took an awful toll. The heavily equipped soldiers, packed tightly into the narrow wooden craft, slumped forward and back as they were hit, making it difficult for the sailors to row. Some were burned as their boats caught fire. Craft were holed and began to sink. Others drifted aimlessly, the men inside all dead or wounded. One of those hit as his boat moved toward shore was the First Dublin’s second-in-command, Maj. Edwyn Fetherstonaugh. The commanding officer, Lt. Col. Richard Rooth, was killed instantly as the boat he was in hit the beach.

In some cases the men leaped out of their boats as they neared land. Many either slipped or failed to gain a footing and went under. They sank like stones in the three-foot-deep water under the weight of their equipment. Some jumped out of the boats as they grounded and hid behind them in the shallows. One of those was Stoker 1st Class William Medhurst. When the boat he commanded grounded, he yelled, “Jump out, lads, and pull her in!” All but one of the other sailors in his boat had been killed and all but three of the Dublins. Medhurst leaped out one side and the other sailor out the other. Both took cover, the seaman with two of the soldiers. As the tide pushed the boat’s stern, Medhurst was exposed to the Turks’ fire and was killed. He left a wife, already a widow with three children. Eighty years later the only memory their daughter had of her daddy was seeing him off at the train station at the outbreak of war. Of the soldiers it was estimated that more than half of the seven hundred men were killed or wounded in their boats. The surf was literally red with blood, and bodies and boats moved aimlessly with the tide: “As the RIVER CLYDE came inshore a very heavy fire from rifles, machine guns & pom poms was directed at her & also on the boats’ tows that ran in alongside soon after. This fire was so accurate that those in the boats were practically wiped out & very few got ashore. Wounded men jumped from the boats & took cover on the far side but were all eventually shot down & drowned.”

Among the casualties was Father William Finn, Catholic chaplain to the First Dublins. The morning before the landing he heard his men’s confessions, said Mass, and gave Holy Communion while their transport was anchored off Tenedos. On April 25, before the Dublins destined to land in the first wave departed, he asked Rooth for permission to join him so that he could minister to the casualties. Rooth reluctantly agreed, and a place was found for the padre in his boat. It was a fatal request. The brave chaplain was wounded in the right arm just after jumping out of the boat, but he continued on to the beach. After making it to land, he began ministering to the wounded but had to hold his injured arm with his left hand in order to give absolution. He was suffering great pain. While blessing a dying Dublin, he was hit in the head by a piece of shrapnel and killed. He had joined the army the previous November from his tiny parish in Market Weighton, Yorkshire, and his were brave actions for a man who was not a career soldier. Days later, when the fighting was over, he was buried. A simple cross was made from the slats of an ammunition crate with the inscription “To the memory of Father Finn” and placed over his grave.

Finn was popular with the other chaplains. In 1916 his friend the Rev. Oswin Creighton, the Eighty-Sixth Brigade’s Church of England chaplain, wrote:

I have … heard that Father Finn asked to be allowed to land with his men, and had been put into one of the first boats, and was shot either getting off the boat or immediately after getting ashore. The men never forgot him and were never tired of speaking of him. I think they felt his death almost more than anything that happened in that terrible landing off the River Clyde. I am told they kept his helmet for a very long time after and carried it with them wherever they went. It seemed to me that Father Finn was an instance of the extraordinary hold a chaplain, and perhaps especially an R.C. [Roman Catholic], can have on the affections of his men if he absolutely becomes one of them and shares their danger.

At a chaplains’ meeting held some weeks later, two, a Presbyterian and an R.C., undertook to see that Father Finn’s grave was properly tended. He was buried close to the sea on “V” beach, and a road had been made over the place. I think they managed to get the grave marked off with a little fence.

The survivors made for a five-foot-high sandy bank, a few yards from the water’s edge, that ran for several yards along the beach. At about that time the River Clyde lowered its gangways, and the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS) machine gunners opened fire against targets they could not see. Drewry and Samson on the Argyll began dragging the lighters towed by their vessel toward the bow of the Clyde. The collier had beached to the left of a rock spit. So, Unwin ordered one of the pinnaces to maneuver the boats into position next to the spit to form a bridge. When the pinnace backed off for fear of grounding, Unwin and Able Seaman William Williams dived in to finish the job. Drewry, who had made it to shore, removed his belt, revolver, and tunic and waded out to help. Together Unwin and Williams pulled on a rope to steady the lead lighter. After forming a precarious bridge with two of the boats, a ship’s cutter, and some planks, Unwin called for the disembarkation to begin: “Within five minutes of the ‘CLYDE’ beaching ‘Z’ Coy. [Company] got away on the Starboard side. The gangway on the Port side jammed, and delayed X Company for a few seconds, and out we went, the men cheering wildly, and dashed ashore with Z Company.”

As the Munsters stepped onto the gangways, they were met with a hail of fire from the ruined forts on their flanks and the trenches in front. Those who were hit fell into the sea or in heaps on the lighters. Bullets also entered the ship through the portals, ricocheting off the steel plates. Some of those hit on the gangways fell backward, knocking the heavily laden men behind them into the sea to drown in the shallow water below: “I sent out my first 2 companies, X under Capt GEDDES & Z under Capt HENDERSON, X on the port side & Z on the starboard. Z got away a little before X. They were to go out by platoons so that there should be no crowding on the lighters. These companies were very gallantly led by their officers. The fire directed on the exits from the vessel being very accurate & men were hit before they left the vessel.”

Capt. Eric Henderson was hit twice on the gangway. Geddes made it to the beach unscathed, but the forty-eight men behind him were felled by machine gun fire. The few who survived made their way to shore to join the Dublins. Together they huddled in a mass under the burning sun, without food and only the tepid water in their quart-sized water bottles to slake their thirst: “We all made, Dublins and all, for a sheltered ledge on the shore which gave us cover. Here we shook ourselves out, and tried to appreciate the situation, rather a sorry one. I estimated that I had lost about 70 percent of my company, 2/Lieuts. Watts and Perkins were wounded and my CQM Sgt. [company quartermaster sergeant] killed. Henderson was wounded. He died from his wounds later. Lieut. Pollard killed, and 2 Lieuts. Lee and Lane wounded, all of Z. Company. Capt. Wilson, the Adjutant, and Major Monck-Mason were wounded on the Clyde itself.”

The plight of those unfortunate Irishmen was watched by men on the transports that were waiting to come ashore. The sight was a distressing one, even from a distance of a thousand or more yards. At 8:30 a.m. on that terrible day, Maj. John Gillam, destined to land at W Beach that afternoon, noted in his diary: “It is quite clear now, and I can just see through my glasses the little khaki figures on shore at ‘W’ Beach and on the top of the cliff, while at ‘V’ Beach, where the River Clyde is lying beached, all seems hell and confusion. Some fool near me says, ‘Look, they are bathing at “V” Beach.’ I get my glasses on to it and see about a hundred khaki figures crouching behind a sand dune close to the water’s edge. On a hopper [Argyll] which somehow or other has been moored in between the River Clyde and the shore I see khaki figures lying, many apparently dead. I also see the horrible sight of some little white boats drifting, with motionless khaki freight, helplessly out to sea on the strong current that is coming down the Straights [sic].”

After an hour of maintaining the floating bridge, a shell exploded, and Williams was hit by a piece of shrapnel. He released his grip on the rope, and Unwin was no longer able to steady the lead boat. It began to drift. He dropped the line in an attempt to save Williams, who died in his arms. Later Unwin would have to be pulled out of the water, the fifty-one-year-old mariner totally exhausted from his exertions. Both men, along with Midshipman Drewry, were awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions that day. For the time being no more troops would leave the collier. It was not until 8:00 a.m., after Drewry and a few others managed to form a bridge between the lighters and the stranded hopper, that men were able to begin landing again. Maj. Charles Jarrett led half of Y Company of the Munsters out of the Clyde and across the new bridge. So many of his men were hit, however, that he sent one of his officers, Lt. Guy Nightingale, from the beach back to the collier to request that Tizard cease the operation. He agreed, and no more troops were sent ashore.

Inside the River Clyde those who had so far been spared the hell of almost certain death on the gangways were not safe either. Despite the navy’s best efforts to silence the guns on the Asiatic side, they failed to hit at least one:

Three shells hit the ship, and then one of the battleships put the gun out of action. The first shell went in the boiler room without killing or wounding anyone; the second hit the ship aft, crashed through No. 4 hold, came through the upper deck, then on the main deck, port side, and took off the legs of two soldiers. They died after about twenty minutes. I was only two yards away from these dear men. The hold was packed with troops as thickly as ever you could stow men together, and the terrible sights and the cries of the wounded will never be forgotten by those who are alive to tell the tale. I often think it was good that one like myself was there, as I did not lose my nerve under fire, and helped to prevent the men from being panic-stricken. I now went down to my men, who were in No. 4 lower hold, and I addressed them, and told them to keep cool, to try and keep their heads as I did …

While I was talking to the platoon another shell came in and killed three of them. This was the second shell I had seen explode within a few minutes; it was rather bad, especially for young lads like these, but I knew I was there to show them an example and take care of them. I have often wondered since what would have happened had that gun not been put out of action when it was; they had the correct range.

Although no more troops landed from the River Clyde that morning, casualties continued to occur. The Dublins who landed at the Camber had done so unopposed, but they were nearly wiped out when they moved into Sedd-el-Bahr Village. The survivors were forced to retreat. With all of their officers gone, most were evacuated by a boat from the Queen Elizabeth. A party of fourteen unwounded survivors linked up with Captain Geddes and two men approaching from the left, but they found that the ruined Fort Sedd-el-Bahr was heavily defended by riflemen and machine guns. They did not attempt to attack. Instead, they moved back to the little bit of cover afforded by the sandy bank on the beach.

At 10:00 a.m. the gun firing on the Clyde was silenced. It was then possible to evacuate wounded off the ship’s stern and for reinforcements to board. At that hour the second wave also started to come ashore. It was composed of men of the Fourth Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, and the other two companies of the Second Hampshires. With them was the commanding officer of the Eightieth-Eighth Brigade, Brig. Gen. Henry Napier, and his brigade major, Maj. John Costeker, Distinguished Service Order (DSO). They traveled in the same boats used by the Dublins three hours earlier, and the awfulness of their journey was clearly evident: “The four boats had already been used that morning. From them some of the Dublin Fusiliers had landed. The boats were much damaged by fire, and blood mixed with sea water ran over the boots of the troops as they sat packed in the laden boats.”

The boats were towed toward the Clyde by a steam launch, which steered toward the starboard side of the collier and the bridge of lighters. As they approached the shore, bullets pierced the sea around them. Men were hit, but not so many as in the first wave. As they neared the lighters, they could see the heaps of dead and dying Munsters piled on them, the mounds of flesh being repeatedly riddled as the Turks fired at the gangways and sally ports. Lt. Col. Herbert Carrington Smith, the commanding officer of the Second Hampshires, called down from the bridge of the River Clyde for the pinnace to take the boats over to the port bow. There they were tied to the lighter nearest the collier. The boats carrying the Hampshires tied up on the starboard side, and the men made it to cover behind the sandbank with only fifteen hit out of fifty.

Arriving at the makeshift bridge, Napier, Costeker, and the Worcesters climbed out of their boats and onto one of the lighters. But they encountered a problem. The lighter nearest the shore had drifted with the current, and the bridge was broken. They were stopped short of landing, and as they stood in the open, wondering what to do next, the Turks took advantage of the inviting targets. The Englishmen could only lie flat and hope to avoid the hail of bullets. Many were hit, including Napier and Costeker. They had gone first into the River Clyde, then returned and tried to cross to shore via the Argyll: “I saw General Napier killed. He went down the gangway just in front of me followed by his Brigade Major Costello [sic]. He was hit in the stomach on the barge between our ship and the beach. He lay for half an hour on the barge and then tried to get some water to drink but the moment he moved the Turks began firing at him again and whether he was hit again or not I do not know, but he died very soon afterwards, and when I went ashore the second time, I turned him over and he was quite dead. Costello was killed at the same time.” So many of the Worcesters were hit that the remainder of the battalion was diverted to W Beach. Those who were not killed trying to land on V were led into the Clyde by their senior surviving officer, Maj. H. A. Carr.

Although the Hampshires suffered only a few casualties and those on the River Clyde were relatively safe, they did suffer two fatalities that day, most notably Carrington Smith. He was hit by a Turkish bullet at about 3:00 p.m. as he stood on the bridge: “Colonel Carrington Smith, who took over command of the Brigade when General Napier was killed, was looking round the corner of the shelter of the bridge through glasses [binoculars] at the Turkish position on shore when he was caught by a bullet clean in the forehead and died instantly.”

The landing at V Beach was ultimately successful, but the loss in men was staggering. What had begun as a creative endeavor turned into a rescue operation by late morning. Men from the Clyde worked to recover the wounded under fire, and more were killed. Sub-Lt. Arthur Tisdall, a platoon commander in the Anson Battalion, led some of his men and RNAS machine gunners into the water to bring in the wounded. Tisdall survived the day and was awarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery. He would be killed on May 6, however, when he exposed his head over the top of a trench. He never knew that he had won Britain’s highest gallantry decoration.

Darkness allowed those still on the Clyde to join the men already ashore, still sheltering behind the sandy bank. It also allowed the wounded to be evacuated. Many would die in the overcrowded, understaffed hell of the hospital ships. First, they were moved to the holds of the Clyde, then evacuated off the stern of the ship. The night was an awful one. Men continued to fall to Turkish bullets, and they had almost nothing to eat or drink. To make matters worse, it rained.

The men of the Twenty-Ninth Division hailed from all over the United Kingdom. They were missed not only by their families and friends but also by the municipalities in which they had been trained and housed. Places such as Coventry and Nuneaton, where the Munsters and Dublins had respectively trained, were particularly hard hit by the V Beach massacre. The colorful career soldiers were popular with the locals and were mourned for years afterward. One story, which appeared in Coventry’s Evening Telegraph of March 7, 1985, epitomizes the feeling of loss that was felt:

Mrs. Procter has unearthed photographs of that time [when the First Royal Munsters were billeted in Earlsdon, Coventry, before departing for Gallipoli] because this year is the 70th anniversary of the disastrous Gallipoli landings of the First World War.

Two of the soldiers became friendly with her parents, who gave them hospitality. They had come in tropical kit straight from Egypt, and found Coventry cold and bleak.

Mrs. Procter, who still has a photograph of the two men, Martin O’Malley and his friend (whose name she cannot recall) and remembers the day they were issued with new boots, when Martin regarded them and said quietly: “I expect they are for my grave.”

Shortly afterwards, the soldiers, who had become part of the Earlsdon scene, having been made welcome by the people with whom they were billeted, marched away.

Everyone waited for news of the Fusiliers, and then came the tragedy of the landings.

Yes, their friend Martin was killed and among his effects was found a photograph of 10-year old Elsie on her cycle.

It was returned to the family with a covering letter and her father had the letter and photograph framed.

Mrs. Procter concludes: “Rather a sad little story serving to illustrate the horror and futility of war.”

Pvt. Martin O’Malley of the First Battalion, the Royal Munster Fusiliers, was from Limerick and was eighteen years old. He was one of those who landed with Major Jarrett and was likely buried in the mass grave filled in by men of the Anson Battalion. After the war his was one of many thousands whose graves could not be identified.

Due to the threat of Turkish snipers and because the men fit for action were needed for the fighting inland, it was not possible to collect the dead for burial until April 28: “I remember that on Wednesday, April 28th, I and a party of men picked up all the dead on the beach and from the water; we placed in one large grave two hundred and thirteen gallant men who gave their lives for their country.”

Maj. John Gillam visited V Beach two days after the landings and arrived there as the Ansons’ burial party was at work:

We dip down to “V” Beach, a much deeper and wider beach than “W,” and walk towards the sea. Then I see a sight which I shall never forget all my life. About two hundred bodies are laid out for burial, consisting of soldiers and sailors. I repeat, never has the army been so dovetailed together. They lie in all postures, their faces blackened, swollen, and distorted by the sun. The bodies of seven officers lie in a row in front by themselves. I cannot think what a fine company they would make if by a miracle an Unseen Hand could restore them to life by a touch. The rank of major and the red tabs on one of the bodies arrests my eye, and the form of the officer seems familiar. Colonel Gostling, of the 88th Field Ambulance, is standing near me, and he goes over to the form, bends down and gently removes a khaki handkerchief covering the face. I then see that it is Major Costeker, our late Brigade Major. In his breast pocket is a cigarette-case and a few letters; one is in his wife’s handwriting. I had worked in his office for two months in England, and was looking forward to working with him in Gallipoli.

It was cruel luck that he was not even permitted to land, for I learn that he was hit in the heart shortly after Napier was laid low. His last words were, “Oh Lord! I am done for now.” I notice also that a bullet has torn the toe of his left boot away; probably this happened after he was dead.

I hear that General Napier was hit whilst in the pinnace, on his way to the River Clyde, by a machine gun bullet in the stomach. Just before he died he said to Sinclair-Thomson, our Staff Officer, “Get on the Clyde and tell Carrington Smith to take over.” A little while later he apologized for groaning. Good heavens! I can’t realize it, for it was such a short while ago that we were all such a merry party at the “Warwick Arms,” Warwick.

The River Clyde remained at V Beach until long after that fateful April day. Later it was towed off and repaired and went on to sail again after the war. The valiant ship’s life ended in 1966, when it was sold for scrap. It was an unfitting end for one of the heroes of the campaign.