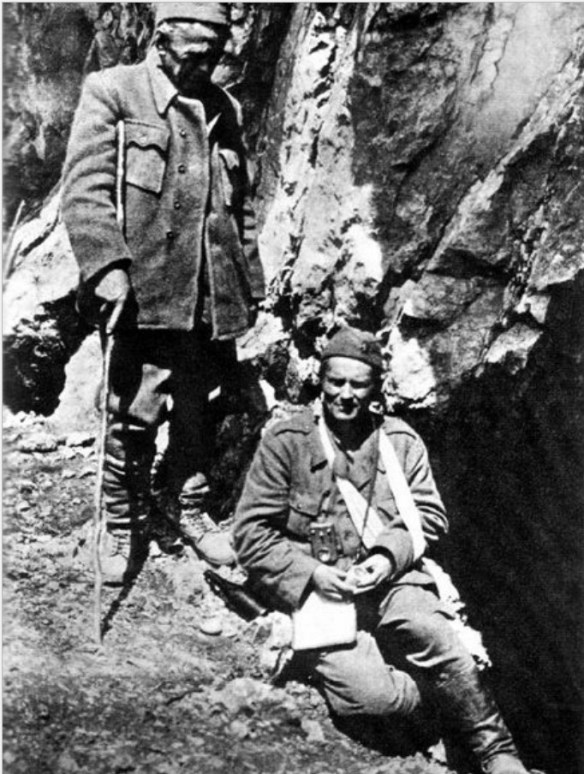

Tito the Partisan leader, his arm in a sling, is pictured with fellow Partisan Ivan Ribar on June 13, 1943, during the Battle of Sutjeska in German-occupied Yugoslavia (today southeastern Bosnia).

Born Josip Broz in the Croatian village of Kumrovec, near Zagreb, on May 7, 1892, Tito—it was a pen name he began using in 1934 in his writing for Communist Party journals—was one of fifteen children in a peasant family. His father, Franjo Broz, was a Croat, and his mother, Marija Javeršek, a Slovene. Both the regions known as Croatia and Slovenia were, at the time, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The family’s farm was not successful, and Josip spent his preschool years mainly in the care of his maternal grandparents. He began school at the age of eight but completed only four grades—repeating the second grade—before leaving school in 1905 when he was thirteen. He moved about sixty miles north, to the town of Sisak, where he worked briefly in a restaurant before apprenticing himself to a locksmith. The Czech who owned the shop, Nikola Karas, encouraged his young apprentice to celebrate May Day and to read a socialist newspaper, Free Word. Broz not only read it, he began selling it.

Broz completed his three-year apprenticeship in 1910 and found work in Zagreb, where he joined the Metalworkers Union and became a labor activist and a member of the Social-Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. After returning briefly to his hometown, he traveled about central Europe as a metalworker and sometimes organized labor actions at major factories, including the Skoda Works in Pilsen, Bohemia, and the Benz auto factory in Mannheim. In October 1912, he lived for a time in Vienna, staying with his older brother, before going to work for Daimler at Wiener Neustadt. Here he gained considerable experience with automotive technology, and he became a notable fencer—as well as a dancer. More important, he expanded his cultural outlook, learning both German and Czech.

Broz was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army in the spring of 1913 and was granted permission to serve with a unit of the Croatian Home Guard, garrisoned in Zagreb. The army sent him to learn to ski during the winter of 1913-1914, at which he became skilled, and he was sent for training at a school for non-commissioned officers in Budapest. He was promoted to sergeant-major of his regiment, the youngest soldier to achieve that rank in the history of the regiment. He further distinguished himself by winning fencing championships in Budapest in the spring of 1914.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 interrupted his socialist activism, and he accompanied his regiment in a march to the Serbian border—to fight Serbia, against which the Austro-Hungarian Empire had declared war. While on the march in August, Broz was arrested on charges of sedition for disseminating antiwar propaganda. He was imprisoned in the Petrovardian Fortress at Novi Sad but was released in January 1915 when the charges were dropped. The details of this incident are unclear, since Broz, in later life, told three distinct versions: he had threatened to desert to the Russians, he was overheard expressing the hope that the Empire would be defeated, he was the victim of a simple clerical error.

He was sent back to his regiment on the Carpathian front and then to the Bukovina front, where his regiment saw heavy action. He showed talent and initiative in action behind enemy lines when he led a scout platoon that captured eighty Russian soldiers. But on March 25, 1915, he was severely wounded by a Circassian cavalryman’s lance, which penetrated his back. Captured, he was held in various Russian POW camps after spending thirteen months in a makeshift hospital in a monastery at Sviyazhsk on the Volga. He survived his wound as well as pneumonia and typhus, and he took the opportunity to learn Russian with the help of two schoolgirls, who had volunteered to nurse the wounded.

Broz was at hard labor in a camp near Perm, working on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and was put in charge of his fellow POWs. When he discovered that Red Cross parcels sent to the camp were being stolen by the Russian staff, he protested, was brutally beaten, and put in a separate prison. At this point, the February Revolution (March 8-March 16, 1917) broke out, and an insurgent mob liberated Broz and returned him to the labor camp. There he met a Bolshevik, who helped him to escape to Petrograd (today St. Petersburg). Later, as Tito, Broz explained that he wanted to join the communist revolution, which he regarded as also a revolution against Austro-Hungarian domination of Croatia. Some historians claim, however, that Broz was simply looking to sit out the war. He did join in the July Days uprising against the Russian Provisional Government that followed the overthrow of the Czar Nicholas II, after which he attempted to escape to Finland, from which he planned to make his way to the United States. Apprehended by agents of the Provisional Government, he was imprisoned in Petrograd and then sent back to the labor camp near Perm but escaped at Ekaterinburg and made his way, by train, to Omsk in Siberia, which he reached on November 8, 1917. Police questioned him there but were deceived by his flawless Russian accent. He joined the Bolsheviks and fought in the Red Guard during the Russian Civil War (1917-1922) before making his way back home in 1920.

The Croatia to which Josip Broz returned was now part of Yugoslavia, the independent nation created by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I. He identified himself as a confirmed Communist, and he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY). In contrast to many of his counterparts in Russia, however, he was a political moderate. This differentiation between his concept of communism and the more radical and absolutist communism promoted by Vladimir Lenin would mark his increasingly profound differences with the Soviet Union throughout the rest of his life and career. He never lost his independence of thought.

The CPY was outlawed in August 1921, Broz was fired from his job as a metalworker because of his overt communist activities, but he continued to work—illegally—for the party. Installed in the CPY district committee, he was arrested in 1924—but acquitted, because the prosecutor, an anti-Catholic, hated the priest who had turned him in. From this point on, however, he and his family were continually harassed by government authorities. He began working in a shipyard in Croatia but was arrested again in 1925 and sentenced to seven months’ probation. The ceaseless government harassment only strengthened his resolve, and he now began a rapid climb up the communist hierarchy, gaining membership in the Zagreb Committee of the CPY in 1927, and in 1928 becoming deputy of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPY, as well as secretary general of the Croatian and Slavonian committees. In August 1928, Broz was again arrested. At trial, he defiantly declared that the tribunal had no right to judge him. As if by way of response, he was sentenced to a prison term of five years.

After his release in 1934, Broz traveled throughout Europe on behalf of the party and wrote for communist journals using the pen name Tito, which, for security reasons and in an effort to protect his family, he adopted and used thereafter. He moved to Moscow in 1935 and was assigned to the Balkan section of the Comintern, the organization of international Communism. In August 1936, Tito was named organizational secretary of the CPY Politburo.

The next year, 1937, was the midpoint of the Moscow Trials (1936-1938), the infamous show trials by which a ruthlessly paranoid Joseph Stalin purged the Soviet communist party. Prominent Yugoslav Communists were among those marked for “liquidation,” some eight hundred Yugoslavs disappearing in the Soviet Union. Action by the Comintern saved the hard-hit CPY from total dissolution, and Tito, a member of the Comintern staff, not only escaped the purge, but, by the end of 1937, was named secretary general by the Executive Council of the Comintern. He returned to Yugoslavia to reorganize the CPY there and was formally named secretary general of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in October 1940.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact—a non-aggression alliance between Stalin and Hitler—was signed on August 23, 1939, stunning the international communist movement, which saw it as a betrayal of communism’s unshakable opposition to fascism and Nazism. Yugoslavia itself was officially neutral when Hitler’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, began World War II, but the religious and ethnic gulf dividing Croat and Serb widened. The Serbs, who made up the majority of the armed forces, were pro-Allied, but the Croats and others, although not opposed to the Allies, were unwilling to challenge the Axis. Ultimately, the issue of Yugoslav neutrality became moot because Germany not only dominated the country’s foreign trade, it also owned a controlling share of its important non-ferrous mines. Early in the war, Yugoslavia’s head of state, Prince Paul (who served as regent to the underage King Peter) repeatedly gave in to German demands for the cheap export of agricultural produce and raw materials. Paul also yielded to Hitler on the matter of Jewish policy, instituting a government program of anti-Semitic discrimination and persecution.

Yugoslavia was in a poor position for opposing Hitler’s juggernaut. Its neighbors, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, had already entered the Axis orbit, and neither Britain nor France could offer military aid for a resistance movement. Yugoslavia was surrounded by Axis powers, continuing to exist at the mercy of Hitler and his fascist ally Benito Mussolini. Indeed, Hitler saw in Yugoslavia an important source of agricultural produce and strategic ores, including copper, chrome, lead, zinc, and bauxite (aluminum ore). Moreover, the nation was geographically positioned to serve as a route of rapid traverse across the entire Balkan region. On March 25, 1941, Prince Paul added his signature to the Tripartite (Axis) Pact, making Yugoslavia an official German ally.

Signing onto the Axis Pact hardly stabilized the country. Serbian nationalists took to the streets and joined various elements of the military to stage a coup on March 27. Prince Paul was overthrown, and a new government was formed under the presidency of General Dušan Simović. The coup, however, failed to end the alliance with Germany, as the Croats, who were part of the new coalition government, demanded that Yugoslavia continue to adhere to the Axis Pact. Fearing a German invasion, the Serb majority agreed—only to be confronted by Hitler, who issued “Directive 25,” ordering an end to Yugoslavian sovereignty.

On April 6, 1941, Germany invaded Yugoslavia, starting with the bombing of Belgrade and followed by ground operations. Government-organized resistance rapidly crumbled, and Yugoslavia surrendered on April 17. Hitler appointed General Milan Nedić to head a puppet government, which administered a program to “Germanize” Yugoslavia, beginning with the genocide of Croatia’s Serb minority as well as Jews, Gypsies, and others the Nazis deemed “undesirable.” Hitler suborned Croats to carry out these programs—an action that instantly and at last galvanized the Serbian will to resist the Axis. A Serb uprising erupted, which was soon organized into a widespread and quite effective Partisan movement.

While the Partisans began their military resistance, King Peter (now free of Prince Paul’s regency) arrived in London in June 1941 and proclaimed a government in exile. Winston Churchill, however, recognized that neither Peter nor his government-in-exile had popular support. Someone on the ground was needed, and, guided by Churchill, the Allies threw their support not behind Peter but behind the communist Partisan leadership of Tito. Churchill intervened to create a coalition between Tito and King Peter by broadly hinting to Tito this would put him into position to take control of most of Yugoslavia after the Germans had been ejected. Churchill was anti-communist to the core, but the war made strange bedfellows indeed, and he knew an effective leader when he saw one. He had no compunction about buying Tito’s cooperation.

It was a spectacularly good bargain for both the Allies and Tito, who led—personally and from the field—his followers in a well-coordinated campaign of sabotage and resistance against the occupying Germans. Not only charismatic and politically astute, Tito was a well-trained military leader and a natural tactician, well-practiced in working behind enemy lines. His Partisan-conducted sabotage and outright combat missions in a political and military movement was so successful that, in the summer of 1942, Tito was able to organize an offensive into Bosnia and Croatia. This forced Hitler to commit disproportionately large numbers of troops in an effort to disrupt the Partisans. Against this counteroffensive, Tito’s Partisans held their own, so that, in December 1943, he was able to credibly announce the formation of a provisional Yugoslav government, with himself as president, secretary of defense, and marshal of the armed forces. By this time, Tito’s forces were a substantial army of about 200,000 men, far larger than the military assets of any other anti-German resistance force in any other occupied European country. This army had succeeded in pinning down thirty-five Axis divisions, about three-quarters of a million soldiers, who would otherwise be fighting the Western Allies in Italy or the Soviet Red Army on the Eastern Front.

With the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, Tito went about the business of establishing his government on a permanent basis. He formed a Politburo within the CPY and held Soviet-style elections in November 1945. In the manner of Lenin and Stalin, he promulgated a Five Year Plan for economic recovery and development. In these efforts, he was greatly aided by his nearly universal popularity as a war hero and patriot. It was, however, the very qualities Stalin both envied and feared. Unlike communist leaders in other countries adjacent to the Soviet Union, it became abundantly clear to Stalin that Tito had no intention of governing Yugoslavia as a Soviet satellite. Tito defined himself as, first and foremost, a Yugoslav nationalist. Only secondarily was he committed to communism.

Tito’s clear defiance of Stalin further enhanced his popularity, not only in Yugoslavia, but in the democratic West. “Titoism” became a new postwar coinage to describe opposition by Iron Curtain countries to Soviet domination. When he died on May 4, 1980, just short of eighty-eighth birthday, he was a living legend in Yugoslavia and around the world. He guided Yugoslavia to economic and ideological coexistence with capitalist nations, which resulted in a standard of living higher than elsewhere in the communist sphere of influence. Nevertheless, his death brought the rapid dissolution of Yugoslavia, as the former ethnic, religious, and local nationalist drives brought about a series of brutal conflicts—especially the Bosnian War (1992-1995) and the Kosovo War (1998-1999)—which were characterized by “ethnic cleansing” and outright genocide.