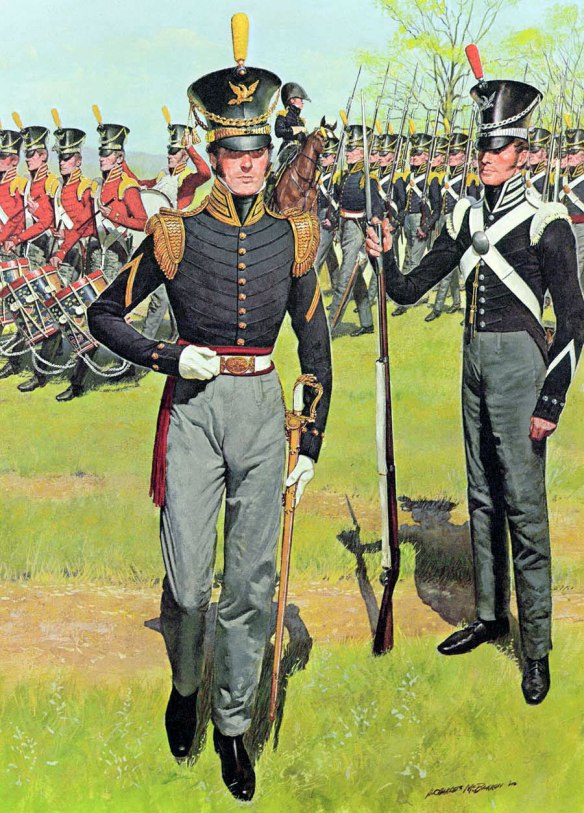

1827

1836

The United States Army had been in existence for nearly sixty years at the time of the Mexican War. During its history, the officers and soldiers had been called on to quell insurrection, repel invasion, and enforce the nation’s laws. Subjected to the whims of Congress, the regular army frequently underwent change. Crises always generated a flurry of legislation affecting the army, increasing or decreasing the number of officers and men to meet the needs of the moment. Once an emergency passed, the drive for economy and the fear of a standing army prompted Congress to slash the army’s budget, sometimes eliminating whole regiments at a time. In 1815, for example, Congress reduced the number of infantry regiments from forty-four to eight. If pressed for troops, the president could always call on the nation’s other military force, the militia.’

The basic structure of the American military was established during the early years of the Republic. The Constitution reserved the office of commander-in-chief for the president, a duty that President James K. Polk embraced during the Mexican War. Although his supporters called him “Young Hickory,” recalling his mentor Andrew Jackson, Polk lacked “Old Hickory’s” martial background. Despite his lack of experience in military affairs, Polk played an active role in planning the strategy of the Mexican War and in the war’s subsequent conduct.’

The nation’s founders placed the defense of the United States in the hands of the War Department. Officially created in 1789 as one of the three original executive departments, the department faced the immense task of overseeing all aspects of the nation’s military, both regular and militia. As secretary of war, the department’s chief occupied a seat in the president’s cabinet. William Learned Marcy filled the office from 1845 to 1849, consulting with Polk on departmental matters, the prosecution of the war in Mexico among them. Born in Massachusetts in 1786, Marcy had been admitted to the New York Bar in 1811. Active in state and national politics, he had held a number of governmental posts, including New York comptroller (1823- 29), New York associate supreme court justice (1829-31), U.S. senator (1831- 32), and governor of New York (1833-39), before joining Polk’s cabinet. Marcy is best remembered for his 1832 address regarding the spoils system, in which he remarked, “To the victor belong the spoils.” Such thinking would play an important role during the Mexican War.

Marcy could not exercise command in the field, as the War Department did not actually constitute part of the army; but through his office he issued the orders that implemented presidential directives and federal legislation that affected the mobilization, deployment, and maintenance of the U.S. Army. The War Department periodically issued guidelines, entitled General Regulations, that set forth the rules of organization and the operation of the military. The last prewar edition had appeared in 1841, but a new edition was published in 1847. In the preface to the new edition, Marcy states, “The General Regulations for the Army, revised and published in 1841, being exhausted, it is found necessary to publish a new edition, . . . so as to embrace alterations and amendments promulgated in orders, or taken from former Regulations, &c.” One major difference between the two editions of regulations is that the 1847 version omits many of the lengthy sections on the army’s staff department. In addition to the Army Regulations, troops were governed by another set of rules known as the Articles of War. Adopted by Congress in i8o6, the Articles of War laid down basic guidelines for behavior expected of officers and enlisted men. So important were these rules that the articles were supposed to be read to all enlisted men twice a year.

A specialized staff, divided into ten separate departments, assisted the secretary of war in managing the standing, or regular, army. The departments included the Adjutant-General’s Department, Inspector-General’s Department, Commissary Department, Medical Department, Ordnance Department, Pay Department, Quartermaster’s Department, Subsistence Department, Corps of Engineers, and Topographical Engineers. Each department oversaw some important aspect of arm’ life and was commanded by a career soldier. All the department chiefs had entered the service either prior to or during the War of 1812. In theory, the general-in-chief coordinated the activities of the departments; but in reality, the department heads often bypassed this link in the chain of command and communicated directly with the secretary of war.

Several categories of officers existed in the army: staff, field, and company. Staff officers planned and supervised strategic and logistical operations. Although the chief of each staff department held the rank of colonel, the ranks of other staff officers below him depended upon their level of responsibility. The second group of officers, called field officers because they were assigned to and commanded regiments in garrison and on campaign, consisted of colonels, lieutenant colonels, and majors. Company officers-captains and lieutenants-composed the third category and commanded the individual companies within each regiment. General officers, the highest ranking category of officers, exercised both staff and field duties.

The issue of rank caused much discord among the officer corps prior to the war and continued to be a sore spot when the army advanced against Mexico. One internal struggle within the corps was between officers of the line (those serving with regiments) and staff officers. Line officers often believed that staff officers received preferential treatment in such important matters as promotions and duty stations. Another equally contentious issue was that of brevet rank. Congress had the authority to bestow brevet, or honorary, rank upon an officer as a reward for good service or heroism in battle. Usually an officer with a brevet, although permitted to use the higher title, did not draw any more pay. However, he could receive the additional pay, as well as fulfill the duties commensurate with the higher rank, when an officer holding the actual rank was not present for duty. Brevet rank had been employed in the army since the War of 1812, and although not entitled to automatically assume the duties and privileges associated with the honor, many older officers had begun to claim that brevet rank actually superseded actual rank. When the army was at Corpus Christi, the debate became so rancorous that President Polk used his position as commander-in-chief to declare brevet rank inferior to actual rank. The decision reversed an early one made by the commanding general of the army, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott. Outraged by the ruling that determined that Col. David E. Twiggs actually outranked him, Bvt. Brig. Gen. William J. Worth left the army just prior to the commencement of hostilities, thereby missing the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. Worth quickly withdrew his resignation and returned to duty, reportedly vowing to earn either a grade or a grave.

Noncommissioned officers (NCOs) formed an important level in the army’s hierarchy. The army’s many sergeants and corporals composed this extremely important class of enlisted men. Noncommissioned officers held their rank at the discretion of their colonels and captains and did not receive a commission from Congress. Each company had five sergeants and eight corporals who supervised the privates while the latter performed their duties. Men who were appointed sergeants or corporals had proven themselves knowledgeable both in the drill and in army regulations. Many had chosen to make the military their career. In accord with their rank, NCOs were entitled to certain privileges, such as a mess separate from that of the privates. The regulations warned officers not to reprimand a sergeant or a corporal in public, as this lessened the NCO’s authority. The senior sergeant, or first sergeant, kept the company’s records, conducted roll calls, and assigned men to various details. The first sergeant also was known as the “orderly sergeant.”‘

Managing the army in war and peace required the coordinated efforts of the army staff departments. These departments kept the army fed, clothed, armed, nursed, and paid, so that it could perform its duties when called upon by the commander-in-chief. Under the direction of the secretary of war and the general-in-chief, the staff departments quietly conducted their operations, engendering cohesion and standardization throughout the military. The officers and men of these departments played a crucial role, albeit one that was unglamorous and often overlooked.

The Adjutant-General’s Department linked the various components of the army together by acting as a clearinghouse for all official correspondence. In addition, the members of the department kept track of the health and whereabouts of all army personnel. Official documents such as general and special orders, morning reports, and court-martial proceedings were deposited in the adjutant general’s office at Washington, D.C. Arms- recruiting also fell under this department’s jurisdiction. Col. Roger Jones, a distinguished veteran of the War of 1812, served as adjutant general.

The Inspector-General’s Department, the smallest of the staff departments, carried out the vital task of evaluating the army’s performance. Officers in this department were attached to the office of the general-in-chief. In peacetime, two permanent members traveled throughout the country inspecting forts and camps; checking on the condition of the buildings, personnel, and material; and evaluating the army’s overall state of readiness. The tasks made it necessary for field officers from permanent regiments (regimental officers with the rank of colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major) to be detached from their units periodically and sent on inspection tours. Although this helped the overworked inspector general, Col. George Croghan, the practice had a detrimental effect on regiments by causing their senior officers to be absent, a problem the army encountered when war broke out.

The Medical Department oversaw the army’s health. In addition to establishing hospitals and dispensing medicine to sick and wounded soldiers, the officers of the department supervised the selection of posts and camps, to insure salubrious settings. Medical officers periodically inspected army provisions for mold, weevils, and worms. Regulations also required army doctors to examine all recruits. The surgeon general, Col. Thomas Lawson, directed the efforts of the Medical Department. The army assigned one surgeon and two assistant surgeons to each regiment. Contract surgeons-civilian doctors hired by the army-sometimes filled vacant positions. The Medical Department consisted of personnel other than surgeons. Hospital stewards (enlisted men with the rank of sergeant) acted as apothecaries and supervised hospital wards in the surgeon’s absence. In times of medical crisis, such as during epidemics or following battles, soldiers were detailed from the ranks to serve as nurses. Women hospital workers, called matrons, cooked and washed for patients. U.S. Army hospitals in Mexico sometimes employed local Mexican women as matrons.”

The men and officers of the army eagerly looked forward to the arrival of the officers of the Pay Department. The paymaster general, Col. Nathan Townson, presided over eighteen paymasters. Although army paymasters held the rank of major, they were not entitled to field command. The department had jurisdiction over all sutlers, civilian shopkeepers whom the government licensed to accompany specific regiments. Although sutlers often inflated their prices, soldiers lined up to buy luxuries that the army did not supply. These government-licensed merchants, who extended credit to men without money, had the right to stand beside the paymaster on payday and collect payment from customers with tabs. Some sutlers followed their regiments to Mexico. Although payday was supposed to occur every two months, on the frontier or on campaign it was common for long interludes to pass between the paymaster’s visits. In such cases soldiers did without cash or had to find other forms of currency. In one instance, volunteers and New Mexican merchants employed buttons, needles, and tobacco as currency when a paymaster failed to visit Santa Fe.”

Soldiers relied upon the Quartermaster Department to fulfill basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter. A permanent staff of thirty-seven officers, headed by Brig. Gen. Thomas S. Jesup, strove to meet this monumental demand. The department’s duties included providing permanent and temporary shelter, as well as transporting and issuing provisions for man and beast. Civilian teamsters, hired to assist the overworked enlisted men assigned to the department, drove the caravans of wagons required to keep the army supplied. Besides American employees, the department hired hundreds of Mexican mule drivers to transport supplies into the Mexican interior. The Quartermaster Department contracted with private ship owners to carry equipment and provisions to Mexico, in addition to operating its own Net of sailing ships and steamboats along the Rio Grande and the Gulf coast. The department also supervised the government workshops and private manufacturers that produced uniforms, tents, knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, and other items for the army. Military storekeepers were quasi-military employees who kept stocks of army supplies, inventorying all goods received and issued at government storehouses. So important were the department’s duties that Quartermaster General Jesup spent several months in Mexico with the army inspecting its operations.”

Army procurement fell under the joint jurisdiction of the Quartermaster Department and the Subsistence Department. Quartermasters had the authority to make purchases in locations where troops were operating, in order to satisfy the army’s immediate needs. Quartermasters bought meat, vegetables, fodder, and draft animals at Mexican markets. Quartermaster funds also covered the cost of transportation and lodging. Bulk rations, such as hundred-pound barrels of beef, pork, flour, and hard bread, were purchased by the eight officers of the Subsistence Department, who tried to secure high-quality provisions at the lowest possible prices. Col. George Gibson, the commissary general of the army, supervised the activities of the Subsistence Department.

Arming the military was the responsibility of the Ordnance Department. In addition to issuing weapons to the army, the department also supervised the production of muskets, rifles, cannons, gunpowder, and accouterments. While the department contracted with some manufacturers to produce arms, it also operated its own arsenals turning out thousands of weapons complete with accessories. These important duties were the responsibility of Col. George Bomtord.”

Although their duties sometimes overlapped, two separate departments of army engineers existed. Officers and men attached to the United States Engineers established and maintained the nation’s permanent posts and fortifications. The corps numbered nearly forty-five officers and was commanded by the chief engineer, Col. James G. Totten. The military academy tell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Engineers. Col. John J. Abort held the office of Chief Topographic Engineer and directed the Topographic Engineers. Officers of this department surveyed routes for new roads and recommended sites for new posts. Active on the western frontier, the Topographic Engineers conducted many mapping expeditions throughout the mid-nineteenth century. Members of both corps figured conspicuously in fighting in Mexico, reconnoitering, marking trails, and supervising the placement of guns.”

Infantry, artillery, and dragoons formed the combat elements of the U.S. Army. On the eve of hostilities with Mexico, the army consisted of only eight infantry regiments, four artillery regiments, and two dragoon regiments. The various companies of these fourteen regiments of infantry, artillery, and dragoons were spread out across the nation at more than one hundred military posts. The war reunited some regiments whose individual companies had not served together for ten or more years.

According to one former army officer-turned-historian, Fayette Robinson, each regiment comprised “a miniature army,” as it contained all the elements of command and staff that existed in the army as a whole. The senior officers of the regiment-colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major and an appointed staff were responsible for the management of the regiment. Officers assigned to the regimental staff helped the colonel carry out his duties. Brevet second lieutenants fresh from West Point were assigned to regimental staffs, a duty that familiarized them with army operations while they gained experience supervising small details. The regiment’s quartermaster and commissary (officers such as the ones just described) provided for the immediate needs of the regiment. Another regimental staff officer, the adjutant, acted as the colonel’s secretary, freeing his commander from mundane paperwork. Selected from among the regiment’s more experienced and promising lieutenants, this important officer helped to mark the regiment’s place on the line of battle and on the march. He also trained the regiment’s noncommissioned officers in their duties and helped manage the regimental band. One surgeon and two assistant surgeons looked after the regiment’s health.”

A noncommissioned staff also assisted the colonel in running his regiment. At large posts, an ordnance sergeant repaired and maintained weapons and munitions in good condition and in working order. The sergeant major, the regiment’s senior enlisted man, acted as the adjutant’s aide. The chief musician-a sergeant-led the twelve-man regimental band that provided entertainment as well as the music to which the army marched and fought. A quartermaster sergeant assisted the regimental quartermaster.’”

Women played important roles in regimental life. Whenever possible, officers’ wives joined their husbands at permanent posts, allowing officers to maintain regular households with their families. Army regulations permitted each company to employ four laundresses to wash and sew for the amen. Like sutlers, laundresses attended payday to collect from soldiers to whom they had extended credit. Most women and children stayed behind when the troops marched off to Mexico; however, American women occasionally are mentioned in the letters and diaries of Mexican War soldiers. Writing on the first day of 1846, Col. Ethan Allen Hitchcock noted the lack of females with the army then camped at Corpus Christi, commenting dryly, “There are no ladies here, and very few women.”

A few women, disguised as men, made their way into the ranks of the American Army during the Mexican War. A woman in the ranks, however, was a rarity and caused a commotion whenever her disguise was penetrated. All known cases of women in the ranks involved volunteers who, unlike regulars, often did not have to undergo physical examination upon enlistment. One Alabama Volunteer passed off a female companion as his frail younger brother until the ruse was discovered. Caroline Newcome took the name “Bill” and served as a private in the Missouri volunteers until pregnancy betrayed her. A similar case occurred in the Mississippi volunteers. Popular attitudes of the day prohibited women from serving as soldiers, and all known cases of females found in uniform ended in disgrace for them and their accomplices.’

To facilitate management and deployment, regiments were divided into smaller components called companies. Ten companies, each commanded by a captain, constituted a regiment. Besides the captain, other positions of command within each company included one first lieutenant, one second lieutenant, five sergeants, and eight corporals. Sergeants performed the functions of quartermaster and commissary on the company level. Each company was divided further into two equal parts called platoons; the platoon, in turn, was divided into two smaller parts called sections. In 1842, Congress had established the maximum strength of each infantry and artillery company at forty-two enlisted men; but sickness, desertion, and detached duty caused the enrollment in companies to fall far below the prescribed number. Wartime legislation prescribed one hundred privates per company. Soldiers considered their company “hone” because they worked, played, ate, slept, and sometimes died within its familial environment. Each member of a company wore a letter denoting his company’s designation: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K. The letter J was omitted, as it was too easily confused with the letter I.

Companies, battalions, regiments, brigades, and divisions provided the army with a simple framework for both logistical and combat organization. The army’s basic building blocks-regiments and companies-could be arranged in various combinations. A military unit of more than one but less than ten companies was designated a battalion and usually was commanded by a lieutenant colonel or a major, depending upon the unit’s size. A battalion usually consisted of companies from the same regiment, but under special circumstances this custom was ignored. A unit larger than a regiment, called a brigade, could be produced by placing two or three regiments together under the command of a brigadier general. Two or more brigades could be placed together under the command of a major general and organized into a unit called a division. Both brigadier and major generals were aided by officers who performed the various duties of the army’s staff departments. Several divisions operating in one theater, commanded by the most senior officer present, comprised an army. The U.S. Army, however, did not retain organized brigades and divisions in peacetime and employed them only in time of war.