Burgoyne now confronted a serious situation. Howe was not going to appear south of Albany to relieve the pressure on his army from the swelling numbers of colonial militia in their path. The losses to the army at the Battle of Bennington had been heavy, nearly one thousand men, or somewhere between 15 and 20 percent of the troops Burgoyne had available along the Hudson. Moreover, the defeat at Bennington had underlined that foraging for supplies would not be in the cards, since any unit engaged in such activities away from the army’s main body was going to be gobbled up by American militia. And to cap it all off, Burgoyne’s supply lines to Canada were tenuous and now open to attack by the Americans. Bennington had demonstrated clearly that the Americans were going to be tough fighters on their own ground. At that point, Burgoyne should have pulled back at the minimum to Ticonderoga, where logistical difficulties would have hampered the colonists from following him while his own supply problems would have eased.

But Burgoyne, ever the gambler, had no intention of withdrawing to Ticonderoga or Canada, since anything less than success would have ruined his military career. Instead, he remained confident that with his professional army he could fight his way through to Albany, where either the colonials would collapse or perhaps Major General Henry Clinton, now in command in New York, could get reinforcements up the Hudson River. Where Clinton was going to mobilize such a force with Howe’s army off in Philadelphia never appears to have entered into Burgoyne’s thinking. It is also likely that since the Bennington disaster had largely involved German troops, Burgoyne believed the Americans could not stand up to the cold steel and fire discipline of British regulars in an open fight.

What he did not realize, since his intelligence was weak, was that the American militia and Continentals defending Albany now numbered more than nine thousand, with their ranks growing daily as new units steadily joined the colonists’ northern army. Their commander was General Horatio Gates, a former British officer who had served in the same British regiment with Burgoyne over thirty years earlier. Gates was a cautious, conservative general, who later in the war would suffer a stinging defeat at the Battle of Camden at the hands of Lord Cornwallis. He would display little initiative in the coming battles near the present-day town of Saratoga Springs. Throughout the Saratoga campaign he argued for a defensive strategy, despite his superiority in numbers, which increased as the days shortened into October. But Gates possessed several aggressive subordinates, most notably Benedict Arnold, perhaps the most competent battlefield commander the colonists would have during the war. These subordinates and Burgoyne’s actions would force the American commander’s hand during the upcoming battles.

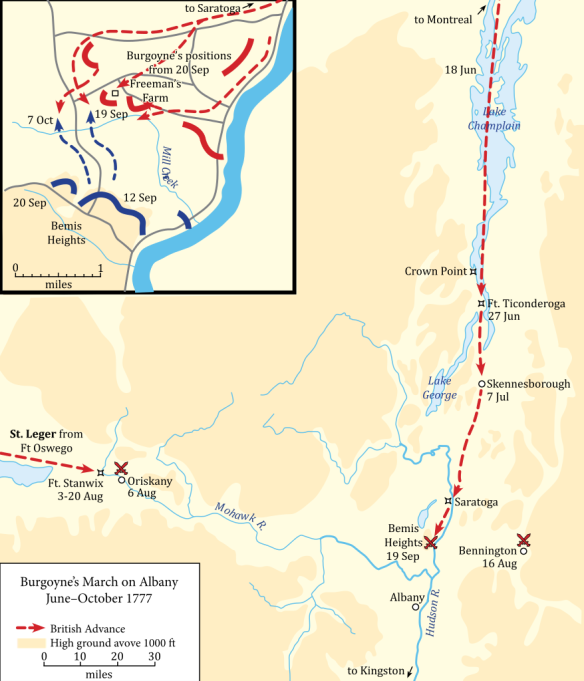

On September 7, Gates ordered his troops to march north from their encampment near Albany. Upon reaching a set of bluffs that faced north ten miles from Saratoga, he had the army halt and construct a set of impressive fieldworks designed by the émigré Thaddeus Kosciusko. The position on what was known as Bemis Heights was close to impregnable, while to the west further bluffs and heavily forested terrain represented an almost impassable barrier to British advance in that direction. The position along the bluffs covered the only track leading south that ran along the Hudson’s riverbank. Ten days later, the British had advanced just to the south of Saratoga within four miles of the American positions, but such was the denseness of the forests lying between that neither side had a clear idea about the location or strength of their opponents. By now, Burgoyne’s forces had declined to barely seven thousand soldiers.

As the two armies prepared for battle, the fall colors of northern New York added a touch of brightness to the grim business of war. Whatever his sense of British superiority, or reports that the colonials were gathering in substantial numbers, Burgoyne knew he must act quickly before his supplies ran out. On September 19, he launched a major attack. His plan called for a feint toward the main American positions on Bemis Heights close to the Hudson, while the attack force swung out to the west and then moved toward the American left flank. Burgoyne’s plan resembled what Howe had done against Washington’s ill-prepared troops in the Battle of Brooklyn the year before. Lord Howe had fixed the Americans in front and then launched a devastating flank attack that had come close to destroying Washington’s army of militiamen. But Howe’s army had been far larger than the one Burgoyne possessed, while the terrain had been relatively open farmland, unlike the forestland of northern New York, which had few open spaces for soldiers to deploy. Moreover, ravines and small brooks cut up the landscape, which would make the movement of artillery pieces difficult.

Brigadier Simon Fraser commanded the attacking force, which consisted of Burgoyne’s best regiments. Its mission was to outflank the Americans, while Burgoyne led the center division both to support Fraser and to provide the final punch, should the Americans come out and fight. Finally, General Friedrich Baron von Riedesel, commander of the German mercenaries, would feint at the main American positions along the river and then move west to support Burgoyne. It all looked clear on paper, but things began to fall apart almost from the moment the British moved into the woods and the trackless terrain inland from the Hudson.

Unfortunately for Burgoyne, the Americans were prepared to meet his effort to outflank their defenses along Bemis Heights. Arnold had persuaded Gates to deploy a portion of the American regiments on the western flank, where a British attack was likely. In fact, Arnold had wanted to push forward most of the American forces on the left wing and fight an attacking, aggressive battle against the British. There, deep in the forest, they could force the British to fight on terrain that would prove thoroughly disadvantageous to European tactics. Gates demurred, preferring to remain behind the fortifications his troops had constructed. In the end, the American commander partially relented and allowed Arnold to push Daniel Morgan’s sharpshooters and Henry Dearborn’s regiment of light infantry forward, where they might be expected to run into the British. Indicative of George Washington’s more acute understanding of the war’s strategic framework had been his willingness to send north a number of Continental regiments, including the two led by Morgan and Dearborn, even as Washington faced Howe’s great army. Here in the northern woods, Morgan’s riflemen pushed forward until they reached the southern outskirts of a centrally located farm belonging to John Freeman (a loyalist, supporting the British), which provided excellent cover to discern any British attempt to outflank the American positions.

The length of the barely cleared farmstead hardly reached one hundred yards from southern to northern edge. Morgan’s men did not have long to wait. In the early afternoon, the skirmishers of Fraser’s flanking troops emerged from the forest gloom into the northern side of Freeman’s cleared acreage. There, they met the murderous fire of Morgan’s sharpshooters, who with precise shots and little smoke at the battle’s beginning picked off nearly every one of the British officers and sergeants. But Morgan’s men then made the mistake of pursuing the routed British skirmishers and ran straight into the main body of Fraser’s advancing troops. The intense firing on the American left led Gates to release a number of militia regiments to support those engaged. Arnold was already leading colonial soldiers in a rush to the front. There was a short pause while both sides reorganized their frontline troops and brought up reinforcements. Then an even fiercer fight exploded as militia regiments arrived on the colonial side, while Burgoyne brought up his main force from the center to reinforce Fraser.

There now ensued a violent struggle over the cleared areas of Freeman’s farm. The center of attention on both sides proved to be the relatively few light artillery pieces the British had dragged through the forest. Always willing to set an example for his troops, Burgoyne, dressed in the spectacular full regalia of a British general, was far enough forward so that colonial sharpshooters were able to pick off his aide and narrowly miss the general. As an experienced soldier, he displayed not the slightest alarm and in fact kept his troops steady and firm in the furious firefight.

The battle lasted for somewhere between three and four hours, with heavy losses on both sides. With little generalship of the classic kind, what had begun as a skirmish devolved into a contest between individual soldiers and small-unit leaders. In the end, Burgoyne had to call on Riedesel to bring as many of his Germans forward as he dared onto the plateau where Freeman’s farm lay, thereby exposing the main British and German camps to an American assault along the Hudson from Bemis Heights. True to form, Gates remained on the defensive while allowing Arnold to conduct the main fight. Later, however, he took most of the credit for the American success, which further exacerbated the tension between the American commander and his overly ambitious but highly competent subordinate.

At the end of the day, the Americans fell back in relatively good order from Freeman’s farm, taking most of their wounded with them. Thus, Burgoyne could proclaim the initial encounter as a British victory, since his troops held the ground at the end of the day. But it was truly a Pyrrhic victory: the British had failed to break into the open and push the American army back on Albany. Their supply situation was now verging on desperate, since there was nothing but dark, forbidding forest in the neighborhood of the British camp. Moreover, combined British and German losses came close to seven hundred men, approximately 15 percent of Burgoyne’s forces—soldiers he could not replace. Although the American losses were slightly heavier, they could be easily replaced, especially as news got around about how the colonial militia had stood up to and battered Burgoyne’s best units.

For Burgoyne, the hard question was what next. His so-called victory had done nothing to improve his strategic position. Certainly the situation was clearer than in the days immediately after Bennington. His army was desperately short of supplies and had shrunk to barely five thousand soldiers. The Americans were far more numerous, with somewhere between nine thousand and twelve thousand available, while Freeman’s farm had indicated that they were tough as well; if they were smart, they would soon use their numbers as well as their knowledge of the terrain to cut the British supply lines to Canada.

Finally, given the British officers’ familiarity with one another, Burgoyne had to know that Clinton would not risk coming north with the minimal forces left to him in New York after Howe had taken the bulk of the army to Philadelphia. At best, Burgoyne could hope that a small raiding force might move up the Hudson to distract the Americans. In such circumstances, most commanders would prudently conclude that there was no other choice but to pull back to Ticonderoga and probably Canada. But “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne was not the sort to risk his reputation by retreating. Rather, he would attack and, if he lost, lose his reputation by way of the vagaries of war.

Matters were not entirely smooth on the American side. Gates and Arnold involved themselves in a fiery quarrel, driven largely by the former’s envy and the latter’s aggressive personality. Arnold was particularly furious that in his report to Congress Gates had taken credit for the fighting at Freeman’s farm and had not even bothered to mention Arnold. In fact, Gates had sat in his tent while Arnold had commanded throughout the engagement. The upshot was that Gates removed Arnold from command and waited for Burgoyne, with whom he had served in the British Army, predictably to attack. Arnold then demanded permission to leave the army, but such was his reputation that every general, save Arnold’s replacement, Benjamin Lincoln, signed a petition asking Gates to allow Arnold to remain.

On October 4, Burgoyne placed his army on short rations, underscoring the precariousness of the British position. He also held a council of war with his senior commanders. He proposed leaving a fifth of the army to guard the camp, while the remainder of the British and German regiments moved out to the west once again to attack the Americans on their flank, a plan he quickly abandoned in the face of the objections raised by his subordinates and the reality of the situation—a situation in which his army had now declined in strength to barely five thousand men, while the American strength was swelling toward twelve thousand militia and Continental soldiers as more and more units arrived from New England and southern New York.

The next day, Riedesel suggested pulling back to the army’s original position on the Hudson and, if relief did not appear from New York, retreating to Ticonderoga and eventually Canada, options Burgoyne had already rejected. That was certainly not to Burgoyne’s liking. Instead, “Gentlemen Johnny” decided on a reconnaissance in force to feel out American positions directly to the south in front of his army. That force would consist of two thousand men—fifteen hundred British regulars and the rest Indians and Loyalists—including artillery, which the attackers would again drag through the woods. Riedsel did not like the proposed operation, arguing correctly that the force was too large to gather useful intelligence, while it was too small to make a successful stand if it came up against significant numbers of Americans. But Riedsel was not in command.

On the morning of October 7, Burgoyne launched his reconnaissance in force, leading it himself and again placing himself in great danger as an example to his soldiers. The movement issued on the far right flank, where the British and German troops had constructed two redoubts to cover the army’s western flank. The redoubts were named for the commanders who had built them, Breymann and Balcarres, and would play major roles in the disaster that was about to enfold British arms. Once again, Fraser led the way. It was a crisp, clear day, with the northern fall foliage still out in all its glory. The combined force, slowed by the fact that it had to build small bridges for the cannons, dragged itself through the woods. It finally arrived at the north end of farmer Barber’s wheat field in the early afternoon, while Burgoyne and his senior officers discussed what to do next.

American scouts had already picked up the movement. Gates then ordered Morgan and his Virginia riflemen, accompanied by Dearborn’s light infantry, to advance north toward the British. Shortly thereafter, Arnold appeared at Gates’s headquarters and asked permission to go forward to see what was occurring. Gates allowed him to do so, but only after extracting Arnold’s promise that he would behave himself, not act rashly, and remain under the direction of General Lincoln. But when Arnold and Lincoln returned, Arnold coldly informed Gates that the riflemen and light infantry were not sufficient to hold the British. Gates exploded and informed Arnold that he had no business with the army and to leave it immediately. Lincoln, however, was able to persuade Gates to commit a larger force. The plan now was for Generals Enoch Poor and Ebenezer Learned to advance their brigades and attack the left (eastern) side of the British line, while Morgan and the light infantry circled around to the west and hit Burgoyne’s right flank. Altogether, more than eight thousand Americans were to be engaged over the course of the fighting—a force far superior to what the British brought to the fight. Helping the Americans even more than their numbers was the fact that much of the fighting would take place in forested and semiforested areas where American tactical skills played to their advantage, while British artillery and close-order volleys lost much of their potency against an enemy that was hard to see and always moving.

The initial American attacks succeeded beyond expectations and quickly collapsed both flanks of Burgoyne’s reconnaissance force. There matters would have remained, with Burgoyne rebuffed but no serious damage done. But then Arnold arrived on the field, having ignored Gates’s order to leave the army. In fact, he had galloped off to the sound of guns as soon as the firing began. Gates sent an officer after Arnold with the order that he was to return immediately. That officer, however, was unwilling to catch Arnold, who had headed straight to the front lines, since, as he later commented, he had no desire to follow a general who was behaving “more like a madman than a cool and discreet officer.”

On arriving at the front, Arnold once again displayed that innate ability that only great combat leaders possess to assess a situation and then act with a ruthless disregard for danger. He promptly grabbed Learned’s brigade and led the militiamen in a smashing charge at the center of what was left of Burgoyne’s line. In the confused fighting, “Gentleman Johnny” had his horse shot from underneath him, while two other bullets pierced his hat and coat. Fraser, the most inspirational of the British officers, went down with a stomach wound that proved mortal that night. The entire British line collapsed, with the survivors falling back on the redoubts, which under normal circumstances should have held against any American attack.

But these were not normal circumstances. Arnold was on the field. At this decisive moment, he first led a charge against the southernmost of the British defensive positions, the Balcarres redoubt. After perceiving that the Balcarres position was too strong, he galloped without suffering a scratch across the entire field in plain view of both sides. Upon reaching the Breymann redoubt, he led Learned’s brigade in a charge that took the redoubt from the rear, while Morgan’s men assaulted it from the front. The position collapsed, and Burgoyne’s army was now in danger of being entirely swamped by the Americans. At last, however, one of the German soldiers managed to wound Arnold in the leg, while another shot his horse from underneath him. With Arnold’s wounding, the impetus went out of the American attack. In every respect, Arnold had been the sole author of the greatest American success of the war. Burgoyne had suffered a devastating defeat. Considering the dwindling numbers left in his army, his casualty figures were dauntingly heavy—British: 184 killed, 264 wounded, 183 taken prisoner; Germans: 94 killed, 67 wounded, 102 taken prisoner—nearly 20 percent of the combined British-German force.

The next evening, the British and their German allies began a dismal retreat. They were in desperate straits, even leaving their wounded behind. Yet instead of speeding the retreat, Burgoyne dallied. For a while, he hoped to cross to the Hudson’s east bank so that the army could retreat to Fort George. However, he soon discovered the colonists were on the east bank in strength. In the face of the American superiority, the fact that there was no clear route of retreat remaining, the lack of rations, and the arrival to the north of the British Army of John Stark and one thousand of his New Hampshire militiamen, where they seized a strong position north of the Batten Kill, the result was inevitable. On October 17, Burgoyne surrendered himself and his troops to their conquerors, the American colonists. As the British and German soldiers passed between the lines of grim-faced American militiamen, the more observant of the British officers noted that while their captors’ clothes were an odd assortment of styles and their bearing was anything but military, they were larger and better framed than their captives and they looked on the beaten with the eyes of hard, proud men.

The surrender of Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga has echoed through American history. Its short-term impact was immediate and obvious. In terms of the strategic and political situation in North America, it ended whatever possibilities the British had to suppress the rebellion. For them, the strategic issue now was not whether they could regain control of their rebellious colonies, but whether they could hold on to the remainder of their empire, especially the sugar islands of the West Indies, which were already fueling the first stirrings of what historians now call the Industrial Revolution. In 1780, Lord Cornwallis would lead an army in the American South with considerable success. Yet it was all a hopeless venture that hardly touched on the strength of the rebellion.

For the Americans, Saratoga would mean immediate aid from France, the leaders of which welcomed the opportunity to pay back their ancient adversaries for the damage the British had inflicted on the French nation in the Seven Years’ War. That aid and the French declaration of war allowed the Americans to place the British on the defensive throughout New England and the Middle American colonies. Moreover, substantial French ground forces in combination with the French fleet played a major role in the second great American victory at Yorktown, which finally forced George III and his ministers to recognize American independence.

The aftereffects of the American triumph would reverberate throughout the world. For France, the cost of a great world war against the British pushed the monarchy’s finances over the brink into bankruptcy. That in turn forced Louis XVI and his ministers to convoke the Estates-General, which had not met for 175 years, exacerbating an increasingly revolutionary political situation that soon overthrew the monarchy and eventually led to a disastrous quarter century of war in Europe. Out of that terrible interlude would emerge the modern state system. Significantly, Ho Chi Minh, the child of both French and Vietnamese nationalism, would draw extensively from the American Declaration of Independence when he declared Vietnam’s independence in 1945.

The long-term consequences of Yorktown would eventually dwarf those of the immediate present. But one should not underestimate the electrifying effect of the victory at Saratoga. Unlike the relative successes of the Concord and Lexington fights and the Battle of Bunker Hill, the victory at Saratoga was a success that involved soldiers and militia from New England, the Middle Atlantic states, and even Virginia. It was in fact the first American victory. And that success would help create a united nation, that great experiment that has now lasted for well over two centuries.