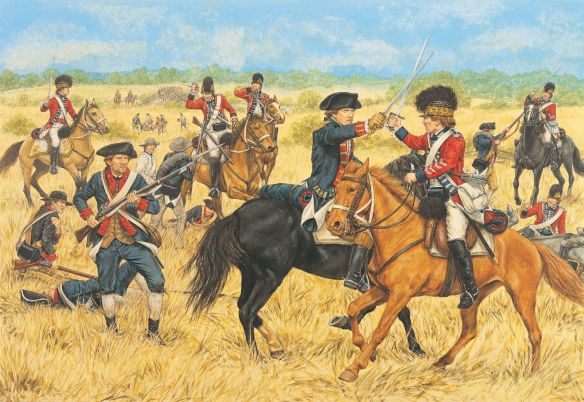

The capture of Lt. Colonel Ramsey at the Battle of Saratoga 1777.

Benedict Arnold in the Breymann Redoubt at the Battle of Saratoga 1777.

Burgoyne’s Surrender at Saratoga, Percy Moran, artist, c 1911.

On July 4, 1776, in a mood of immense enthusiasm and optimism, the representatives of the thirteen American colonies had signed the Declaration of Independence. Thirteen months earlier, the militia of New England, reinforced by volunteers from as far away as Virginia, had shot to pieces British regulars at the Battle of Bunker Hill; only the fact that the colonists ran out of ammunition had prevented them from winning a crushing victory. By spring 1776, the British had had to withdraw from Boston. But almost immediately after the Continental Congress declared the colonies’ independence from Great Britain, the nascent nation’s strategic situation collapsed in a welter of defeats. The British Army, under the command of General Sir William Howe, had badly battered the Americans in late summer and fall 1776, driving them from Brooklyn, then Manhattan and Westchester, and finally from what were then called the Jersies. At times, it seemed as if the British redcoats were going to entirely destroy the colonists’ ill-equipped, ill-trained army of amateurs.

As 1777 dawned, the political and strategic situation of Britain’s rebellious colonies appeared desperate. Admittedly, the Americans’ leading general, George Washington, had won several small skirmishes at the turn of the year, but the victories at Trenton and Princeton were hardly sufficient to encourage Britain’s European enemies to help the rebels. And now the British were concentrating their military power, intent on ending the rebellion that year. The major British force in North America, occupying New York City, could choose from a number of strategic options: It could move directly through the Jersies to strike at the colonists’ capital at Philadelphia; it could strike north along the Hudson River; or it could use the Royal Navy to transport it to virtually any point along the coasts of the rebellious colonies.

Equally threatening in spring 1777 was the large army that the British had built up in Canada, this one under the command of “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne, playwright and sometime general. For all his posturing, Burgoyne was a serious student of military affairs who had for his time an enlightened view about how officers should treat their soldiers. Not surprisingly, unlike most British officers, he had an excellent rapport with the common soldiers, who regarded him with both respect and admiration. Nevertheless, he also had a British aristocrat’s contempt for the plebeian, common Americans, who had dared rebel against the crown. Burgoyne’s army was now poised to drive up the Richelieu River from Montreal, cross Lake Champlain, and then drive down the Hudson from Lake George to Albany. A combined offensive by Burgoyne and Howe, with their two armies meeting at Albany, could thereby seize control of the Hudson River valley. Strategically, such a campaign, if successful, would split the New England colonies from the other colonies and allow the British to divide and conquer their rebellious subjects.

However, the British generals failed to cooperate in their efforts in 1777. Much of the confusion in British strategy had to do with personalities, both those in London and those in command of British forces in North America. The tyranny of distance was also a contributing factor. A crossing of the Atlantic took on average six to eight weeks, if one was lucky; important dispatches could take four to five months to reach their intended recipient. Under such circumstances, cobbling together and maintaining a coherent strategic approach between London and British forces in North America was next to impossible. In his last speech before the House of Commons, William Pitt, Britain’s great strategist during the Seven Years’ War and severe critic of George III’s policy of intimidation toward the American colonies, had warned Lord North’s government: “Three thousand miles of ocean lie between you and them. No contrivance can prevent the effect of this distance in weakening government. Seas roll, and months pass, between the order and the execution; and the want of a speedy explanation of a single point is enough to defeat the whole system.”

Equally important in the failure of the British strategy was the fact that two of the principal actors in the development of that strategy—Lord Germain, secretary of state for the American Department, who was responsible for the running of the war among King George III’s ministers; and “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne—had little understanding of the difficulties the American wilderness would pose, not only to the advance of a European-style army, but to its logistical support as well. Germain had never been to the colonies, while Burgoyne’s experience had been limited to short periods in Boston, when the colonists had besieged the town in 1775, and in Canada after the British had abandoned that city and New England in 1776. Moreover, like most members of the British upper classes, both considerably underestimated the willingness and ability of the colonists to fight in defense of their recently proclaimed independence.

After the British withdrawal from Boston in April 1776, Burgoyne had moved to Canada to become the chief subordinate of General Sir Guy Carleton, the governor in chief, but had then returned to London at the end of the year. There he persuaded Germain to place him in command of an army in Canada that would drive south from Montreal to Albany and meet up with Howe’s army moving north from New York City. Unfortunately for British fortunes, Burgoyne’s underlying assumptions about his proposed campaign were to prove disastrously faulty. The logistical difficulties were by themselves daunting. The terrain through which the British would move would favor the colonists, a factor that anyone who had been involved in Jeffery Amherst’s British and colonial efforts in the area during the Seven Years’ War would have known. Moreover, Burgoyne and Germain believed, as was to be the case with virtually every British commander in the war, that only a small portion of the population supported the rebellion and that a substantial reservoir of Tory sentiment would rally to the British Army once it arrived.

Finally, and most disastrous, Burgoyne and Germain assumed Howe would move north to meet the invading force from Canada. It would not be until he reached Saratoga that “Gentleman Johnny” would learn that Howe had set off on an extended campaign to seize Philadelphia and destroy Washington’s Continental army. In fact, Howe failed to support the move from Canada because Germain neglected to inform him that the government expected him to support Burgoyne. To get to Pennsylvania, Howe decided not to advance across the Jersies, because he believed the logistical difficulties of supporting a campaign from New York into Pennsylvania would prove too great. Instead he took his army all the way south by sea to the entrance to the Chesapeake before landing in Maryland and marching from that point on Philadelphia. British forces remaining in New York under Sir Henry Clinton were insufficient to mount a major campaign to support Burgoyne. At best they could launch a raiding force up the Hudson, which they were eventually to do. Although that force enjoyed some success, capturing West Point and reaching and burning Kingston, then the capital of the colony of New York, it could reach no farther and eventually had to fall back to New York City, then consisting only of a small portion of the island of Manhattan.

And so Burgoyne would end up going it alone. Although he was not informed that Howe planned to move against Philadelphia, it is doubtful Burgoyne would have changed his plans, such was his confidence in his army and contempt for the martial qualities of the colonists. Burgoyne arrived in Canada in early May 1777 to inform Carleton that he was not to command the army to invade the colonies, but rather would remain in Canada to command the troops Burgoyne, having chosen the best regiments, would leave behind.

The majority of Burgoyne’s army consisted of British regulars, men who had enlisted for a number of reasons: for drink, to escape the boredom and poverty of their life, and in many cases to avoid the hangman’s noose—in eighteenth-century Britain there were more than three hundred crimes for which one could be hanged. The discipline imposed on the enlisted ranks was savage, brutal, and swift for even the most minor offenses. The other portion of the army consisted of German mercenaries, recruited from the minor states of Brunswick and Hesse. Frederick the Great was so contemptuous of the minor princes hiring out their subjects to the British that he imposed a cattle tax on the troops that crossed his territory on their way to North America. The Germans were under the same harsh discipline as British soldiers. Whatever merciless regime they were subject to, the British and German soldiers formed highly trained, cohesive, and responsive combat units of the highest quality. But Burgoyne’s soldiers had been trained to fight in the open, on relatively flat terrain. In such circumstances they would be virtually unbeatable—if they could find such locations in the wilderness of the northern colonies.

Burgoyne’s plan to reach Albany had two major components. The main force, under his command and totaling approximately seven thousand British and German soldiers, with a sprinkling of Indians and Tories, would follow the route up the Richelieu River and then use Lakes Champlain and George and the Hudson River to reach Albany. These numbers would begin to shrink before his troops engaged in serious combat with their American enemies, since as he moved south, he would have to garrison the major points his army captured, such as Forts Ticonderoga and Edwards. At the same time a second force, approximately one thousand men under Barry St. Leger consisting of a mixture of Tories, regulars (two hundred British and more than three hundred Germans), and Indians, moved from the west using Lake Ontario and the Mohawk River to join Burgoyne at Albany. Colonists under the future traitor and brilliant soldier Benedict Arnold defeated that arm of the British advance with relative ease.

In late spring, Burgoyne and his army began their march south. As his British and Germans proceeded, Burgoyne, displaying the qualities of a bad playwright rather than a general, issued a histrionic proclamation that announced his intention to liberate the colonists from “the unnatural rebellion” under which they were suffering. Nevertheless, if the colonists failed to greet their liberators with proper respect and affection, he continued, “I have but to give stretch to the Indian forces under my direction, and they amount to thousands, to overtake the hardened enemies of Great Britain and America. I consider them the same wherever they might lurk. The messengers of Justice and Wrath await them in the field; and devastation, famine, and every concomitant horror that a reluctant but indispensable prosecution of military duty must occasion, will bar the way to their return.” Burgoyne could have produced no tract better calculated to stoke the anger as well as the fear of the Americans than to indicate that the British were unleashing the fury of an Indian war not only on the frontier, but deep into settled areas of the colonies as well. The reverberations of Burgoyne’s missive echoed and reechoed deep into New York and New England, even reaching Maryland and Virginia.

The campaign opened with what appeared to be brilliant success. By late June, Burgoyne’s forces, shielded by their Indian allies, had reached Fort Ticonderoga. The defenders were thoroughly ill prepared; the fort itself had been badly placed, so that if an enemy gained the heights of Sugar Loaf Mountain and placed artillery on those heights, the fort itself would become indefensible. The Americans failed to guard the mountain, the British pushed artillery to the heights, and Ticonderoga fell without a fight. Burgoyne then sent a detachment under Brigadier General Simon Fraser in pursuit of the routed rebels.

But in a nasty little fight at Hubbardton, the Americans put up stiff resistance against Fraser’s troops. The fight was definitely not out of the Americans. While the colonials suffered heavier casualties, they inflicted losses on the British that in the long run Burgoyne could not afford. Moreover, again distance and the necessity to maintain contact with Canada had a significant impact on the British. Burgoyne had to leave four hundred soldiers to garrison Crown Point to guard his ammunition supplies and another nine hundred to ensure that Ticonderoga would remain in British hands to protect his lines of communication.

The question now confronting Burgoyne was how to conduct the next stage of the advance on Albany. There were two possible routes, both with their defects. Originally, he had planned to move from Lake Champlain across to the northern portion of Lake George and utilize that body of water to move south to the Hudson. This presented several difficulties. First, there was no road between the two lakes; second, the rough terrain between the two virtually precluded the timely construction of a road and the easy movement of the army and its supply train. The other option was the route that ran between Skenesborough and the Hudson. Several factors led Burgoyne to choose this route. First was the fact that the lead elements of his army had already reached Skenesborough. Choosing the Lake George route would have forced him to pull the army back a considerable distance. Second, it was only sixteen miles from Skenesborough to the Hudson, a much shorter distance than the first route. It seemed a simple matter of having the army cut its way through the forest and construct a road to ease the passage of artillery and supply wagons. Surely such a task would represent no great difficulty?

What looked straightforward on the maps turned out to be a nightmare born of Burgoyne’s ignorance of American terrain. Those sixteen short miles consisted of pure, primeval wilderness. To add to the challenges involved in building a road in such trackless terrain, the Americans, as they retreated south, cut down huge trees into tangles of branches and trunks into which they rolled boulders, dammed up streams, and caused other mischief along the route the British had chosen. Nature with its insects, heat, humidity, rain, and dark, wild forests made its contribution to ensuring that the task of those cutting their way south with axes and saws was a dismal one indeed. While the British, now moving at a snail’s pace, chopped their way through to the Hudson, the colonials were gathering their forces.

Nevertheless, when the British arrived on the Hudson, the troubles they had encountered thus far seemed to owe more to the terrain and distance than to the Americans. Matters were soon to change. War parties of Indians joined up with the British at Skenesborough on July 17, where Burgoyne unleashed them in the belief that his army could control them. In fact, the Indians waged war as they always had, scalping, killing, and raping anyone unfortunate enough to cross their path, including a certain Jane McCrea, the beautiful fiancée of a Tory officer in Burgoyne’s army. Several Indians captured her and her companion and murdered, scalped, and stripped her. Jane’s fiancé then recognized her scalp on the belt of one of the Indians. Burgoyne attempted to punish the murderers but met with little success. Outraged that the British chief wanted to subject them to the white man’s laws, large numbers of the Indians proceeded to desert. On the other side, the incident was a windfall for colonial propagandists. Within a matter of weeks, the story had spread all the way to Virginia.

On August 3, Burgoyne at last received the extraordinary news of Howe’s movements. According to a message smuggled through the lines, Howe was not advancing up the Hudson to meet the invading army from Canada in Albany. Instead, he was taking himself and his army off to Pennsylvania by way of the Chesapeake. Here was Burgoyne’s opportunity to change his plan of campaign. Supplies were already running short as the logistical lines to Canada lengthened. The Americans were hastening reinforcements northward from as far away as Virginia. Nevertheless, Burgoyne resolved to proceed southward as if nothing had changed.

Ensconced in his new position at Fort Edwards on the Hudson, “Gentleman Johnny” decided to launch a foraging expedition eastward into Vermont and Massachusetts and then down the Connecticut River. His initial plan called for a jaunt that would have been almost two hundred miles in length. The purpose of the raid was twofold. First, it was to forage extensively to strengthen the army’s supply base and capture horses for the German cavalrymen who had arrived in Canada with no mounts. Equally important in Burgoyne’s calculations was the belief that a large number of Tories would rally to the British forces marching through the countryside. Nothing better illustrates the extent to which the British underestimated the colonists as well as their misconceptions about the political attitudes of the population they intended to bring to heel.

Piers Mackesy, the great historian of the British side of the war, acidly dissected the expedition’s composition:

The commander [whom Burgoyne] chose was a brave German dragoon called Colonel Baum who qualified for marching through a country of mixed friends and foes by speaking no English. His force was remarkable. He had 50 picked British marksmen and 100 German grenadiers and light infantry; 300 Tories, Canadians, and Indians; to preserve secrecy, a German band; to speed the column, 170 dismounted German dragoons in search of horses, marching in their huge top boots and trailing their sabers. They were reinforced on the march by 50 Brunswick Jäger and 90 local Tories.

The expedition was about to run into a buzz saw of opposition. New England and New York were up in arms at the threat of Indian massacres that Burgoyne had raised at the beginning of his march, fear and anger that the murder of Jane McCrea had served only to exacerbate.

Moreover, one of the most competent battlefield commanders the colonies were to throw up during the war, a certain John Stark, was leading a substantial number of New Hampshire militia toward Bennington as Baum moved out from the Hudson. Stark was hard-core indeed. He had been captured by the Indians before the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War and then had so impressed the Iroquois by his bravery that they had made him a member of the tribe. Stark returned home, and with his knowledge of the Indians along with a natural talent for leadership, he subsequently became one of the most effective lieutenants in Rogers’ Rangers during the Seven Years’ War. At Bunker Hill, he led his militia regiment with exceptional skill in holding the far left of the line. At Trenton, it was his troops who broke the Hessians’ last attempt to stand with several well-timed volleys. Yet the Continental Congress failed to promote Stark to brigadier general, instead advancing a politically connected individual from New Hampshire who had little military experience. An infuriated Stark resigned his commission and returned home to his farm. Burgoyne’s threat to New England combined with his promise to unleash the Indians brought Stark back to lead the troops the state’s legislature called up. The only requirement Stark levied on the legislature in accepting his commission was that he would be responsible only to New Hampshire and not to the Continental Congress or its officers. A hard man, John Stark.

Several thousand New Hampshire men promptly joined up with Stark to fight the invaders. The men Stark was leading represented an interesting military force. Although the young farmers among them were inexperienced in military affairs, their leaders were not. Eighteen years earlier, the British had mounted a major military effort up the Hudson River valley and on to Montreal to drive the French from Canada. Their regulars had borne the bulk of the fighting, but supporting them was a large force of militia units drawn from New England and upstate New York. The soldiers in the militia regiments had experienced the rigors of campaigning, observed the strengths and weaknesses of the “lobsterbacks,” learned a modicum of drill, and occasionally fought short, sharp skirmishes with the French and Indians. Those men now served not only as the top leaders of the Revolutionary army, but as junior officers and sergeants buttressing the militia units that had begun to gather as soon as the colonists had received word of the British invasion from Canada. Thus, the militia facing Burgoyne’s army was much more than a mob of hardscrabble farmers; they were made of tough, proud men led by individuals with considerable military experience.

The target for the British raid, selected by Burgoyne largely because it was the agricultural center of southern Vermont, was Bennington. As Baum advanced at a maddeningly slow pace, Stark and his New Hampshire militia arrived in the town to find a swelling number of militia units from the other New England states. Alarmed by his first contact with the colonists, who were gathering in larger numbers than expected, Baum requested reinforcements. Burgoyne then dispatched another contingent of Germans under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Breymann, a military pedant of the worst sort. Constantly ordered by Breymann to order and reorder their ranks, his soldiers failed to reach Baum before the fighting began.

Meanwhile, Stark assumed de facto command of the colonial troops, and the two forces ran into each other in a pouring rain on August 15. As the weather cleared on August 16, Stark announced to his troops: “There are the redcoats and they are ours, or Molly Stark sleeps a widow tonight.” A combination of superior numbers and broken, wooded terrain gave the Americans a distinct advantage. That afternoon, Stark struck. His militia units outflanked Baum’s force after pinning the German grenadiers in their redoubt. Following some stiff fighting along the center of Baum’s line, the German defenses collapsed under attack from both their flanks and front, with the remnants fleeing back the way they had come. The routed British and German soldiers then ran into Breymann’s soldiers slowly approaching the battlefield. The colonials proceeded to maul that force badly, although darkness prevented them from destroying the second German force as they had Baum’s. The Germans, Tories, and British scrambled through the darkness back to the safety of the main army.