Clockwise from upper left: Brigadier General August V. Kautz, Brigadier General James H. Wilson, Confederate artillery firing across the river.

Union Army commander Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant did not want a siege, but the battle had proved unsuccessful. He had been through one siege already in this war, at Vicksburg. It had lasted 47 tedious days, and the inactivity had made it difficult to maintain discipline and morale in the ranks. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was stronger than Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton had been, and Petersburg was better defended, with several supply routes still open. A siege here would last much longer than at Vicksburg and would be more stubbornly contested. Nevertheless, on June 20 1864 Grant told Butler and others, “I have determined to try to envelop Petersburg.”

That same day he also set in motion one last attempt to force Lee out in the open. His army now lay across the Norfolk & Petersburg Railroad east of the city and was in striking distance of two more of Lee’s remaining sources of supply: the Weldon Railroad, which ran into North Carolina and on to the port of Wilmington, and the Southside Railroad, running west to Lynchburg. If he could cut these lines, even temporarily, Lee might be forced to attack him or to abandon Richmond and Petersburg altogether.

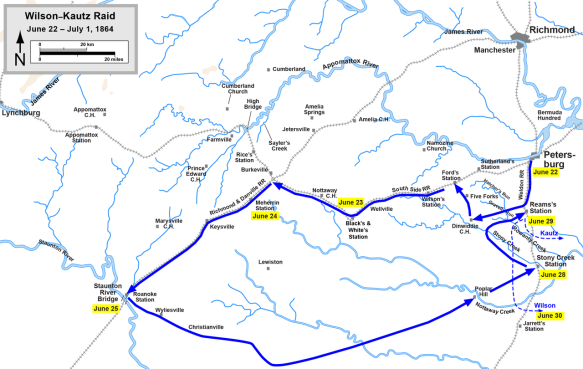

Grant ordered General Wilson to take his own cavalry division and Kautz’s on a wide sweeping ride around the enemy right. Grant wanted Wilson to cross the Weldon line as close to Petersburg as possible, cut it, then ride on to the Southside, once again as close to the city as practicable. Then he was to tear up track as far west as he could get, if possible the entire 45 miles to Burke’s Station, where the Southside intersected with the Richmond & Danville line.

From there, if still unmolested, Wilson and Kautz were to continue the destruction, moving southwest on the Richmond & Danville. If they were successful, only one line – the Virginia Central – would be left intact to serve the Army of Northern Virginia.

Grant expected that Sheridan, who was on his way back east from the Trevilian raid, would keep most of Wade Hampton’s cavalry occupied, though Rooney Lee’s mounted division would have to be dealt with. As further cover for the movement, Grant ordered Birney and Wright to move to their left, across the Jerusalem Plank Road and out to the Weldon line in the vicinity of Globe Tavern. They might do considerable damage to the railroad themselves, and they would also provide a screen behind which Wilson could get well on his way.

Wilson asked for two days to rest and refit his men. Then, before dawn on June 22, he set out with a total of about 5,000 troopers. By midmorning they had reached Reams’s Station on the Weldon line without opposition; they stopped briefly to burn the railroad buildings and uproot the tracks for a few hundred yards on either side. That done, the raiders moved on, and by afternoon they passed through Dinwiddie Court House, with Rooney Lee now snapping ineffectually at their heels.

Before nightfall Wilson and Kautz reached Ford’s Station on the Southside line, where they had the good fortune to find two loaded enemy supply trains. These they burned, along with the station buildings and everything else combustible. Then they headed west, tearing up the track as they went, heating it red-hot over fires fed with railroad ties and then twisting the rails out of shape to render them useless. Not until mid- night did the Federal raiders finally halt, more than 50 miles from their starting point. The exhausted men slept with their reins in their hands, lying in formation in front of their saddled horses.

The following morning, while Kautz’s men rode ahead toward the Richmond & Danville line, Wilson’s men continued their work, moving slowly west while Rooney Lee’s cavalry skirmished in their rear. “We had no time to do a right job,” a trooper complained. Now they simply overturned the rails and ties, which could be done quickly but was hardly a permanent form of destruction. The next day they reached Burke’s Station and met Kautz, who had reduced the depot to a charred ruin and had torn up the Richmond & Danville line for several miles in either direction.

Kautz took the advance again and headed out, reaching the Staunton River 30 miles southwest of Burke’s Station on the after- noon of June 25. Destruction of the bridge here would be a hard blow to the Confederates, but by now the raiders were expected. More than 1,000 home guards, supported by at least one battery, waited in earthworks on the far side of the river. When Kautz advanced to burn the bridge, the defenders opened a stubborn fire and drove the Federals back. At the same time, Rooney Lee was pressing Wilson’s rear guard. Wilson decided it was time to end the raid and return to friendly lines.

For several reasons, this was not going to be easy. Wilson was 100 miles from safety, with tired animals and worn-out men. General Hampton was on his way back to the Petersburg area with his two divisions of Confederate cavalry. And friendly lines were not where Wilson thought they were. Wright and Birney had moved their corps as ordered on June 22, but they had become separated in the woods, and A. P. Hill’s Confederates had shoved their way between them. Hill stopped Wright short and forced the Federals back. Then he struck Birney ferociously and threw him back to the Jerusalem Plank Road, taking 1,700 prisoners. As a result, the Weldon Railroad was still firmly in Confederate hands.

At midday on June 28, Wilson’s weary riders reached Stony Creek Depot, just 10 miles south of Reams’s Station, and presumed safety. But here they ran into Wade Hampton’s and Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry divisions. The dismayed Wilson could not break through; his line of retreat was cut off and he was in real trouble.

That night Wilson ordered Kautz to ride west and north, around the enemy divisions to Reams’s Station; Wilson would hold Hampton at Stony Creek. While Wil- son fought off a substantial attack, Kautz reached Reams’s Station the next day – only to discover, instead of the Federal II and VI Corps, part of Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry and two brigades of Hill’s Confederate infantry.

Increasingly desperate, Wilson next took his own command around the opponents facing him to rejoin Kautz west of Reams’s Station. But now the enemy was converging on him from three sides: Fitzhugh and Rooney Lee’s cavalrymen from the north, Hill’s infantry from the east, and Hampton’s riders from the south. There was no choice but to make a headlong run for it.

The Federals burned their wagons, spiked their guns, left their wounded behind and headed southwest. Before they could get away, the Confederates attacked and Kautz, in covering the escape of Wilson, became separated from him.

There was a large swamp on the enemy left flank, and Kautz thought he saw a chance to break through there. “It was our only chance,” wrote one of his troopers. In they plunged, the men riding past Kautz, who was sitting astride his horse, one leg slung over his pommel, with a pocket map of Virginia in one hand and a compass in the other. Looking at the sun for position, he pointed out their course. Incredibly, the troopers got through the swamp unopposed. Seven hours later, bone-weary and falling asleep in their saddles, they rode into friendly lines southeast of Petersburg.

Wilson’s men had it even tougher. For 11 hours they were pursued south, until they were nearly 20 miles farther away from Federal lines. Wilson allowed the men two hours’ rest, then he led them east, toward the James River. Riding all day June 30, with Hampton racing to cut them off, the Federals finally reached Blackwater River – seven miles south of the James – after midnight, on July 1.

There was no enemy on the other side of Blackwater River, but Wilson found the only bridge burned. Hastily the troopers made makeshift repairs and straggled across; that afternoon they reached the James and safety, having covered 125 miles in 60 hours. “For the first time in ten days,” Wilson wrote later, his men “unsaddled, picketed, fed, and went regularly to sleep.” Like most cavalry raids in this War, Wilson’s had been audacious, dramatic – and had yielded mixed results. Undeniably the destruction of more than 60 miles of railroad track was important. Years later Colonel Isaac M. St. John, who was in charge of Confederate ordnance supplies in Richmond, said that nine weeks passed before another train entered either Petersburg on the South-side Railroad or Richmond on the Richmond & Danville. The ensuing shortages forced Lee’s army to consume every bit of its commissary reserves, yet it was not forced out of Petersburg, much less Richmond. Meanwhile, Wilson had lost all of his artillery, wagons and supplies, along with one quarter of his command in casualties.