OPERATIONS FLOWN

LIST OF Operations flown by the Corpo Aereo Italiano:

24 October – night raid – Felixstowe and Harwich

27 October – night raid – Ramsgate

*29 October – daylight raid – Ramsgate

1 November – daylight fighter sweep over Kent

5 November – night raid – Felixstowe and Ipswich

8 November – daylight fighter sweep over Kent

10 November – night raid – Ramsgate

11 November – daylight raid – Harwich

17 November – night raid – Harwich

20 November – night raid – Norwich

23 November – daylight fighter sweep over Kent*

25 November – daylight fighter sweep over Kent

27 November – night raid – Ipswich

28 November – daylight fighter sweep over Kent

29 November – night raid – Ipswich and Harwich

5 December – night raid – Ipswich

13 December – night raid – Harwich

21 December – night raid – Harwich

22 December – night raid – Harwich

2 January 1941 – night raid – Harwich

*This was the only other raid intercepted in strength by Fighter Command. Twelve Spitfires of 603 Squadron attacked off Folkestone claimed seven CR.42s shot down and two probables. Two CR.42s were actually shot down and several others damaged. (Coincidentally, it was also the day that Belgium formally declared war on Italy.)

The Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) was instructed by Mussolini in 1940 to send a force to northern Europe to `assist’ the Luftwaffe in its campaign against Britain – unfortunately Göring and the Luftwaffe High Command were not so enthusiastic and reasoned that they could probably manage without them. Even so, a force named the Corpo Aereo Italiano was formed under the command of Generale sa Rino Corso- Fougier in September 1940.

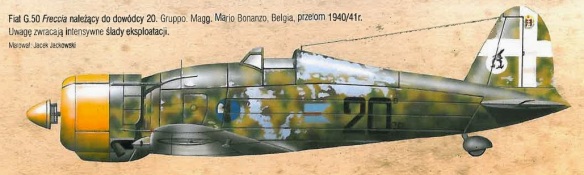

The organisational structure of the Regia Aeronautica was broadly similar to the RAF, comprising `Stormo’ (Wings) which had a number of `Gruppo’ (Groups) which, in turn, consisted of several `Squadriglia’ (Squadrons). The formation had two `Stormo’ of Fiat BR. 20 twin- engined bombers; the 13 th and 43rd. There was also one `Stormo’ of fighters, the 56 th , which had two `Gruppo’. The 18 th `Gruppo’ was made up of three `Squadriglia’, equipped with Fiat CR. 42 bi-planes, and the 20 th `Gruppo’ with three `Squadriglia’ of Fiat G. 50 all-metal monoplanes. Finally, there was an assortment of transport, communications and reconnaissance machines; in total, a force of around 200 aircraft.

DESTINATION BELGIUM

In late September, under orders to commence operations against mainland Britain, the Corpo Aereo Italiano headed north to their assigned bases in Belgium. First to leave Italy were the Fiat G. 50 fighters. After heading off on 22 September they landed at their first stop-over at Treviso, where they remained until 6 October having been delayed by fog. Next stop was Bolzano, where they spent 11 more days waiting again for suitable weather, this time in order to attempt a crossing of the Alps, then on to Munich, Frankfurt and finally Ursel. The Fiat CR. 42 bi-planes made the journey with comparative ease.

A total of 77 Fiat BR. 20 bombers attempted the four-hour flight over the Alps and direct to Belgium on 27 September, but only 60 made it all the way. Two aircraft were completely destroyed and the remaining 15 were scattered along the route, having landed due to mechanical failures.

The men and machines were a strange sight to the Germans, the men having been issued with newly designed Luftwaffe-style uniforms to replace their First World-War style tunics and `breeches’. However, their machines retained the bright `camouflage’ which was rather better suited to the sunnier climes of the Mediterranean.

When news of Corpo Aereo Italiano’s arrival reached the Belgian Government, now exiled in London, they declared war on Italy. The Corpo Aereo Italiano came under the command of the Luftwaffe’s Fliegerkorps 2 and was allocated the area from Ramsgate to Harwich over which to operate. On the evening of 24 October 1940 the first attack was launched – a night raid by 18 BR. 20 bombers on Harwich and Felixstowe. Only minutes after take-off one of the BR. 20s crashed, killing its six crew. Ten crews reported that they had successfully bombed the target, but on their return two aircraft were wrecked and one badly damaged.

The first daylight raid was made on 29 October. This was an elaborate and large-scale raid on Ramsgate in Kent made by 15 BR. 20 bombers with a fighter escort of 39 CR. 42s, 34 G50s and a few Me109s from the Luftwaffe. The armada flew along the Channel and then swung in over the coast at 10,000 feet near Ramsgate – all in formation as if at an air show. On the ground the anti-aircraft gunners were at first baffled by the sight and the unusual `rattling’ noise that the engines made – quite unlike RAF or Luftwaffe aircraft – but after further deliberation began firing anyway. 75 bombs fell in the area and the Italian press could be truthfully told that their air force had indeed attacked England. Remarkably, and most fortuitously for the Italians, Fighter Command did not appear in the sky. Five bombers were hit by the gunners, but all returned to Belgium.

On November 11 at midday ten BR. 20s, each loaded with three 250kg bombs, took off from Chievres with the intention of attacking Harwich. They were to be escorted by a strong fighter force of 42 CR. 42s, 46 G. 50s and a few Me109s from the Luftwaffe, but almost immediately the G. 50s and Me109s turned back in the face of bad weather, leaving the ten bombers and 42 CR-42 bi-planes to carry on.

By the time the raid was nearing the English coast heavy cloud and poor visibility had scattered the aircraft into small groups spread over several miles, each unable to see the others.

In England the coastal Chain Home and Chain Home Low radar stations had spotted the incoming raid and 12 Group scrambled the Hurricanes of 17 and 257 Squadrons. Flights from two already airborne squadrons, 46 and 249, were also vectored towards the incoming raid.

257’s nine Hurricanes, Red, Blue and Green sections, were led by the Canadian Flight Lieutenant HP `Cowboy’ Blatchford, `Red 1′ who sighted the bombers flying on a north-north-west heading at 12,000 feet some 10 miles east of Harwich. 17 Squadron, with which they were to rendezvous, was spotted 7,000 feet below and took no part in the engagement. As Blatchford led his squadron to gain more height, two formations of fighters were seen some miles away, one above and one below the bombers. `Cowboy’ Blatchford later recalled his part in the battle for a BBC broadcast:

“When we were about 12,000 feet up, I saw nine planes of a type I had never seen before, coming along. Bombers, big and fat, like flying slugs. They were in a tight V formation. I didn’t like to rush in bald-headed until I knew what they were, so the squadron went up above them to have a good look. Then I realised that at any rate they were not British and they were armed and that was good enough for me. I led the boys in from the back, line abreast. We went into attack starting with the rear starboard bomber and crossing over to the port wing of the formation. It was then, when we got in close, that I saw the Italian markings.

“They kept their tight formation and were making for the thick cloud cover at 20,000 feet, their gunners firing all the way. But our tactics were to break them up before they could reach the clouds and we succeeded at the second pass. Two of them were badly shot up and when they dropped out the others started turning in all directions. I singled out one of the enemy and gave him a burst. Immediately he went he went straight up into a loop. I thought he was foxing me – trying to make me break off – as I had never seen a bomber do anything so violent before. He was right on his back. I thought to myself the crew must be rattling around inside there like peas – unless, of course, they were strapped into their seats. Anyhow, I followed him when he suddenly went into a vertical dive. I still followed, waiting for him to pull out. Then I saw a black dot move away from him and a puff like a white mushroom – someone baling out. The next second the bomber seemed to start crumpling like a wet newspaper and it suddenly burst into hundreds of small pieces. They fell down to the sea like a snowstorm.

“I think my burst must have killed the pilot. I think he fell back, pulling the stick with him – that’s what caused the loop. Then when the plane fell off the top of the loop, he probably slumped forward again, the weight of his body putting the plane into an uncontrollable dive. She kept on building up speed. What usually happens then is that the wing or tail falls off, and it was a surprising sight to see the plane just burst into small pieces.”

MERRY-GO-ROUND

The CR. 42 fighters had now caught up with the bombers and Blatchford began to engage one of them in a quarter-attack:

“We did tight turns, climbing turns and half-rolls ’till it seemed we would never stop. That Italian could certainly fly! Neither of us was getting anywhere until one of my bursts seemed to hit him amidships and for just a moment he looked to be `waffling’. Suddenly he did something like an `Immelmann’ turn and came in at me head-on. I went into a diving turn and we started all the merry-go-round business all over again. I got in two or three more bursts and this time knocked some fair sized chunks out of his wings and fuselage. Then my ammunition ran out. That put me in a bit of a fix and I didn’t know what to do next. I was afraid if I left his tail he would get on mine the moment I broke off. So we kept on this turning and twisting routine until suddenly – more by luck than judgement – I found myself bang on his tail only 30 yards ahead and a few feet higher.

“If I had even a dozen bullets I could have finished him off easily. It was enough to make anyone swear. In a flash I decided that if I could not shoot him down, I would try and knock him out of the sky with my aeroplane.

“I went kind of haywire. It seemed to me that the biplane was only made of boxwood and string and could not possibly damage a Hurricane. But just as I started to close with him, I had second thoughts and decided I would just try scaring the living daylights out of him. I aimed for the centre of his top main- plane, did a quick little dive and pulled up just before crashing into him. The idea was to pass very close over his head and maybe send him into a spin. I felt a very slight bump and a shudder and reckoned I must have misjudged. I climbed and circled, but I never saw him again. Somehow, I don’t think he got back.”

`Cowboy’ Blatchford knew his Hurricane was damaged for the engine and airframe were vibrating badly, so he set off back to Martlesham Heath. However, his day wasn’t over:

“As I was flying back, keeping a good look-out behind, I saw a Hurricane below me having the same kind of affair with a Fiat as I had just had and run out of ammunition. I went down and did a dummy head-on attack on the Italian. At around 200 yards he turned away and headed out to sea. Again I thought: `Good! I really can go home this time’ but just before I got to the coast, still keeping a good look-out behind, I saw another Hurricane with three Fiats close together and worrying him. So I went down again, feinting another head-on attack, and again when I was about 200 yards away the Italian broke off and headed for home.”

When 257 Squadron’s Intelligence Officer, Flt Lt Geoffrey Myers, compiled the squadron’s report of the action he added: `On landing, two blades of Flt. Lt Blatchford’s machine had 9 inches missing and the propeller was found splashed with blood’.

Blatchford’s actions that day, particularly in coming to the assistance of the two Hurricanes whilst being out of ammunition, led to the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

TUCK’S LUCK AND MACARONI BOMBERS

On hearing of 257 Squadron’s success a press photographer was sent to RAF Martlesham Heath in order to take a series of photos recording the historic engagement with the Italians. Prominent among the resulting images is Squadron Leader Robert Roland Stanford Tuck DFC, the enigmatic CO of 257 Squadron at the time.

However, Tuck took no part in the combat of 11 November whatsoever. On that day he was suffering from ear-ache, caused by problems with an ear-drum, and the squadron’s Medical Officer had grounded him. Tuck therefore set off to hunt a few rabbits nearby and saw `his’ Hurricanes fly over him as they were scrambled. Already, Tuck had developed a reputation for considerable good fortune and his various adventures and hair’s-breadth escapes had led to the sobriquet `Lucky Tuck’. Today, though, his `luck’ had deserted him and he was grounded and unable to join what he later called a `turkey shoot’.

The newspapers, though, were not necessarily specific that Bob Tuck had not taken part. Indeed, in The People journalist Arthur Helliwell reported on `Chianti Tuck’ and went on to make a racially disparaging remark about Italians before announcing that: `For weeks he and his men had been waiting for just such an opportunity. They descended upon the Macaroni airmen like avenging furies and played swift havoc among these ancient `planes from Rome. `They were easy’ he (Tuck) said `Just dead meat of the skies.’

Later, Tuck would profess to have been embarrassed by this embellishment of facts although it has to be said that he exhibited no shyness or reticence when it came to posing with his pilots and their trophies that had been `liberated’ from the downed Italian machines.

AERIAL PICNIC

As a BR. 20 had fallen close by, `Cowboy’ Blatchford, Bob Tuck and Karol Pnaik immediately set off in a car to have a look. It is widely reported that the crew were still at the crash site under guard of the local police and that the body of Armando Paolini, the wireless operator, was still in the wreck. This was certainly how things are recorded in Tuck’s biography by Larry Forrester `Fly For Your Life’:

`Just inside the door the top gunner was still in his harness, swinging gently, and full of bullets. The harness creaked faintly and the floor beneath him was slippery. They had to flatten themselves against the side of the fuselage to wriggle past. On the way Tuck looked up and saw a holster at the gunner’s waist. He reached up, extracted a Beretta automatic and stuck it in his pocket. Since ten years of age he’d been a keen collector of firearms, he still couldn’t resist a chance to augment his personal armoury.

`In the waist they found two hampers, large as laundry baskets. One was stuffed with a variety of foods – whole cheeses, salami, huge loaves, cake, sausages and several kinds of fruit. The other held still more food, and over a dozen straw- jacketed bottles – Chianti.’

Two steel helmets and a bayonet were added to the collection, and finally they cut four badges from the aircraft’s twin tails with the bayonet, the resulting holes clearly visible in `photos of the wreck. Meanwhile, the triumphant RAF pilots headed back to their airfield with this aerial picnic. The day’s events were surely going to be celebrated in style.

Whilst the British press made much of the Italian’s use of apparently `outdated’ bi-plane aircraft, and just a few hours after the Italian air force had ventured to attack the British port of Harwich, Britain launched its own attack on shipping in an Italian port, also using bi-planes. This, of course, was the port of Taranto, and the bi-plane torpedo bombers were Fairey Swordfish of the Fleet Air Arm. Three Italian battleships were put out of action, and in one night the Italian fleet had lost half its complement of capital ships.

The tables had certainly been turned, and in a fashion so spectacular that it only served to highlight the miserable and embarrassing failure that had been the Italian raids over Britain’s east coast. Prime Minister Winston Churchill was later prompted to comment of the Corpo Aereo Italiano’s attempted interference in Britain’s domestic affairs by saying: “They might have found better employment defending their fleet at Taranto.”

Despite the fact that British newspapers of the period rather poked fun at this Italian escapade and intimated that the Italians had run for home at the first sight of opposition, this was certainly not the case. The intercepting RAF pilots noted that their opponents flew skilfully and with spirit and courage, particularly in the face of superior opposition. `With Valour To The Stars’ is the Italian Air Force’s motto. They had certainly flown with valour albeit they hadn’t reached Harwich, let alone the stars, that day.

COMBAT THE FINAL TALLY OF PILOT CLAIMS CAME TO:

BOMBERS: Seven BR. 20s destroyed

FIGHTERS: Five CR. 42 destroyed, Three probables, One damaged

Although referred to by some of the Hurricane pilots as a `turkey shoot’ they would have been amazed to know the true number of aircraft lost. According to Italian records, only three BR. 20s and three CR. 42s were actually brought down in the engagement, although `misclaiming’ of this nature was quite normal, for all sides, particularly in large-scale aerial engagements.

Of the BR. 20s, MM22267 of 242 Squadriglia flown by Sottotenente Enzio Squazzini and MM22620 of 243 Squadriglia flown by Sottotenente Ernesto Bianchi crashed into the sea. As parachutes had been reported the Aldeburgh lifeboat was launched, but found only one empty parachute.

MM22621 of 243 Squadriglia flown by Sottotenente Pietro Appiani made a crash landing near Woodbridge.

The CR. 42s were MM6978 of 83 Squadriglia flown by Sergente Enzo Panicchi, which went into the sea. MM6976 of 85 Squadriglia flown by Sergente Antonio Lazzari, which crash landed near Corton Railway Station, and MM5701of 95 Squadriglia flown by Sergente Pietro Salvadori which landed near Orfordness.

The worsening weather caused further losses on their return to Belgium. Four BR. 20s crash landed near the coast and 18 CR. 42s made emergency landings with varying degrees of damage. Sergente Mario Sandini wandered over Amsterdam, where he crashed into a town square and was killed.