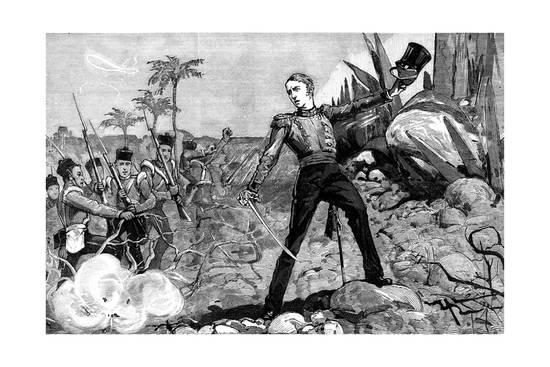

Storming Myat-Toon’s stronghold, February 1853, Burma, a biographical sketch of Lieutenant General Garnet Joseph Wolseley (1833-1913), illustration from the magazine The Graphic, volume XXVI, no 675, November 4, 1882.

In India, the years 1851–54 were full of minor campaigns and military expeditions: there were operations against the Waziris in 1851–52; there was an expedition to the Black Mountains to punish tribesmen for murdering two collectors of the salt tax, and two small expeditions against the hill tribes around Peshawar during 1852; and in 1853 there was an expedition against the Jowaki Afridis. And, of course, in 1854 there was the Battle of Muddy Flat in China. All in all, however, these were comparatively peaceful years for the Empire – except in Burma.

The cause of the Anglo-Burmese difficulty was similar to the cause of the Opium War. Burmese officials had insulted and abused British subjects. This, of course, was not to be tolerated. In a minute on the subject, Lord Dalhousie wrote that the Indian Government, meaning his own, could not ‘appear in an attitude of inferiority or hope to maintain peace and submission among the numberless princes and peoples embraced within the vast circuit of empire, if for one day it gave countenance to a doubt of the absolute superiority of its arms, and of its continued resolution to maintain it’. On 15 March 1852 Lord Dalhousie sent an ultimatum to the King of Burma. On 14 April Rangoon was taken by assault.

There had been considerable resistance to the British invasion of Burma and some sharp fighting had taken place in Rangoon, particularly around the beautiful golden-domed Shwedagon temple complex, but the Burmese army had been driven out and fled north. In December Dalhousie imperiously informed the King of Burma that he planned to annex the province of Pegu (Lower Burma), and that if the king objected the British would take over the entire kingdom. On 20 January 1853 Pegu was formally annexed to British India without even the usual treaty. So ended, at least officially, the Second Burmese War. A third war would be waged before the century ended, and between the wars there was a great deal of plain fighting, though not on a scale grand enough to be called war.

A subaltern still in his teens, Garnet Wolseley (1833–1913), arrived in Burma a few months after the annexation and here saw his first action. Although born into the British military caste, his family was poor and had not been able to buy him a commission. But his father and grandfather had had honourable military careers and because of this the Duke of Wellington had been persuaded to give him a commission when he was eighteen. He had the proper outlook for a young Victorian officer: the belief that ‘marriage is ruinous to the prospects of a young officer’, a fierce desire for military glory, and the conviction that all English gentlemen were born courageous.

Military glory is a ridiculous thing; it is also appalling. Yet it fascinates men, and its achievement is thrilling to those who pursue it and survive more or less intact. No man ever sought glory on the field of battle more assiduously than Wolseley. Sent to India, he ‘longed to hear the whistle of a bullet fired in earnest’, and at first was very much afraid that he would miss the Second Burma War. He need not have worried. Bands of guerrillas and dacoits still harassed the British forces and one of these, led by a chief named Myat Toon, was enjoying considerable success. To the British, Myat Toon was a bandit; to the Burmese he was a national hero. Such differences of opinion usually result in bloodshed. A naval and military force was sent to subdue him – or rather two forces, one military and the other naval; the navy captain and the army colonel, although marching by the same road, did not coordinate their plans. The result was a disastrous defeat. Naturally another expedition was called for to redeem British prestige; this time a larger force under the control of a single officer.

Brigadier Sir John Cheap of the Bengal Engineers was chosen to command this little expedition, which is remembered now only because young Wolseley took part in it. Cheap’s force of about one thousand men was made up almost equally of Indian and European troops. Although there were a few European regiments (composed of white Britons) in the army of the East India Company, most of the European regiments in Asia were ‘Queen’s Army’, meaning they were part of the British regular army on loan to the Government of India. ‘Queen’s officers’ tended to take a snobbish view of this distinction, looking down on ‘Company officers’ and doing everything possible to indicate their own superiority. Wolseley described a difference in dress:

The Queen’s Army took an idiotic pride in dressing in India as nearly as possible in the same clothing they wore at home. Upon this occasion [in Burma], the only difference was in the trousers, which were of ordinary Indian drill dyed blue, and that around our regulation forage cap we wore a few yards of puggaree of a similar colour. We wore our ordinary cloth shell jackets buttoned up to the chin, and the usual white buckskin gloves. Could any costume short of steel armour be more absurd in such a latitude? The officers of the East India Company were sensibly dressed in good helmets with ample turbans round them, and in loose jackets of cotton drill. As a great relaxation of the Queen’s regulations, our men were told they need not wear their great stiff leathern stocks. This was a relief to the young recruits, but most of the old soldiers clung to theirs, asserting that the stock protected the back of the neck against the sun, and kept them cool. I assume it was rather the force of habit that made them think so.

Thus dressed, General Cheap’s force left Rangoon at the beginning of March 1853 in river steamers. The trip up the Irrawaddy was disagreeable: the troops were crowded on the decks of the steamers and exposed to the fury of tropical storms and to swarms of hungry mosquitoes; they also passed a number of rafts fitted with bamboo frames on which were stretched in spread-eagle fashion the corpses of Myat Toon’s enemies. After a few days on the river the force landed and started the overland march to Myat Toon’s stronghold. There was some skirmishing along the way and Wolseley saw a man killed in action for the first time: ‘I was not at the moment the least excited, and it gave me a rather unpleasant sensation.’

On their first day ashore the troops bivouacked 500 yards from a stream where a detachment of Madras Sappers were building rafts while Burmese across the stream sniped at them. Wolseley, unable to resist the sound of the firing, went down to the stream to watch the sappers work and to see how he himself would react under fire. While there, a British rocket section opened up on the Burmese and the scream of the rocket caused some of the sappers’ cart bullocks to panic and stampede towards him. As he sprinted for the shelter of some carts, an old soldier, watching him run, called out, ‘Never mind, sir, you’ll soon get used to it.’ Young Wolseley was furious.

For twelve days the British moved forward through the jungle; the food was bad and scanty, and cholera pursued them. At last they reached Myat Toon’s stronghold, a fortified village, and a general assault was ordered. Unfortunately the 67th Bengal Native Infantry chose to lie down rather than advance. Ensign Wolseley gave one of the native officers a kick as he ran by him. Included in Cheap’s column were 200 men of the 4th Sikhs. Having finally conquered the Sikhs, the British had hastened to enlist these splendid fighters in their own army, and this was the first time they had been in action on the British side. According to Wolseley, ‘They were an example of splendid daring to every one present.’

The first attack on Myat Toon’s position failed. When volunteers were called for to form a storming party, Wolseley and another young officer quickly offered to lead it. ‘That was just what I longed for,’ Wolseley said. Many years later, when Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, full of years and honours, was asked if he had ever been afraid during a battle he had to admit that while there was not time to be afraid during the action he was sometimes nervous beforehand: ‘I can honestly say the one dread I had – and it ate into my soul – was that I should die without having made the name for myself which I always hoped a kind and merciful God might permit me to win.’ Such must have been the only fear of many a young British officer in the nineteenth century. It reflected an attitude that made Britain great and strong.

Collecting a party of soldiers, Wolseley led them cheering down a narrow nullah towards the enemy’s defences while the Burmese manning them cried, ‘Come on! Come on!’ For a few moments Wolseley was in a state of ecstatic excitement. Then he fell in a hole. It was a cleverly concealed man trap and he was knocked unconscious. When he recovered his senses and managed to crawl out, he found that the storming party had melted away and there was nothing for him to do but run back ignominiously. It was not glorious.

A second storming party was called for, and again Wolseley volunteered. Writing of his experiences more than forty years later, he described his emotions as he led this second charge:

What a supremely delightful moment it was! No one in cold blood can imagine how intense is the pleasure of such a position who has not experienced it himself; there can be nothing else in the world like it, or that can approach its inspiration, its intense sense of pride. You are for the first time being, and it is always short, lifted up from and out of all petty thoughts of self, and for the moment your whole existance, soul and body, seems to revel in a true sense of glory. … The blood seems to boil, the brain to be on fire. Oh! that I could again hope to experience such sensations! I have won praise since then, and commanded at what in our little Army we call battles, and know what it is to gain the applause of soldiers; but in a long and varied military life, although as a captain I have led my own company in charging an enemy, I have never experienced the same unalloyed and elevating satisfaction, or known again the joy I then felt as I ran for the enemy’s stockades at the head of a small mob of soldiers, most of them boys like myself.

This time the attack succeeded, but Wolseley fell when a large gingall bullet passed through his left thigh. He tried to stop the bleeding by putting his hand over the wound and saw the blood spurting between the fingers of his pipe-clayed gloves. Nevertheless, he cheered and shouted and waved his sword, urging his men to charge on. This was Wolseley’s last battle in Burma; he was invalided home, promoted to lieutenant, and recovered in time to serve in the Crimea.