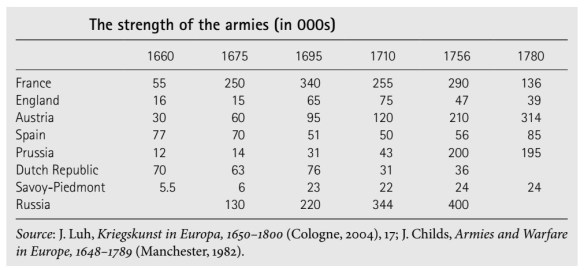

Yet the transformation most evident in Ancien Régime armed forces was that of numbers and scale. Even the most exaggerated assertions about the size of armies raised in the century before 1650-most of which have no foundation in army rolls or muster details, and all of which ignore fluctuations between and within campaigns-are still dwarfed by the scale of the war effort sustained by armies and navies from the 1690s onwards.

To some extent the technological and consequent organizational change indicated above could account for an upward pressure on the scale of armed forces, and perhaps especially the size of forces concentrated on the battlefield. But it would not of itself have generated the growth in military establishments on the scale seen in the decades from the 1680s to the eighteenth century. The great increases in this period were not primarily driven by military factors and their implications, but were a consequence of the conduct of international politics. Louis XIV’s inept and threatening diplomacy throughout the 1680s drew France inexorably towards a war against a coalition of every other major west-central European power. Holding her own against this alliance after 1688 required an unparalleled military effort. France’s enemies responded with a scale of mobilization which would collectively match and surpass the 340,000 soldiers and 150,000 tonnes of naval force that France managed to throw into the struggle. Military expansion moved eastwards in the mid-eighteenth century, where the triangular contest between Prussia, Austria, and Russia in the decades after 1740 had the same effect on army growth. Frederick II inherited an army of 80,000 in 1740, but the wars over Silesia pushed this up to 200,000. Austrian military expansion following the disasters of the 1740s was no less impressive, while exploitation of lifetime conscription ensured that Russia overtook all other European states in military manpower. The final driver of military-this time naval-expansion was European colonial and trade rivalry and warfare, and above all the determination of the British to maintain oceanic naval supremacy over any other European power. The Royal Navy, which reached a peak of 196,000 tonnes in 1700, underwent progressive increases through the 1750s when the total rose through 276,000 tonnes up to 473,000 tonnes by 1790. This increase in the size of British naval force was not surpassed by any other European power, but the attempt to build forces that were at least comparable stimulated naval growth throughout the eighteenth century. Whether this reflected the ambition of combined French and Spanish Bourbon fleets to challenge the British in the Atlantic, or concerned the exercise of naval power by Russia and the Scandinavian powers in the Baltic, the net effect was a steady growth in the size of naval forces, and for most states this naval growth moved in step with demands for massive land forces.

Yet European powers in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries proved able to sustain these increases; states did not collapse under the burden of maintaining armed forces. It is not easy to explain this in terms of rising prosperity, demographic, or economic growth. For in west-central Europe the biggest military increases coincided with a long period of economic stagnation from 1650 to 1720/30. In this later seventeenth and early eighteenth century, Britain and the United Provinces were exceptional in achieving broad-based economic growth. France and the German or Italian states saw ever-more troops and revenues being extracted from peoples barely able to meet these demands. In contrast, it was certainly the case that from the 1730s European rulers began to benefit from economic and demographic growth. Economic progress fostered technological improvement and cheaper production of military goods such as reliable cast-iron cannon for both navies and land armies. A mid-century transformation of agriculture allowed more efficient land-use, which had effects on military operations through a steady growth in the populations which provided army and navy personnel. But the largest military expansion had occurred before these advantages came into play, in states whose economies remained depressed and limited.

Because the huge growth in military force achieved by rulers like Louis XIV, Charles XI of Sweden, Frederick-Wilhelm I of Prussia could not be attributed to expanding economic and demographic potential, a traditional and now easily-derided response was to shroud the process in a mysterious and frequently circular set of assertions about the personal power and capability of `absolutist’ monarchs. A slightly more plausible interpretation argued that this military growth was the result of growing bureaucratic and governmental effectiveness. Better-assessed taxes collected under the threat of military coercion allowed further tax increases, which in turn made possible further growth in the armed forces. Armed forces and central authority are assumed to grow in a single, internally-cohesive process. It is indisputable that the character of Ancien Régime armies would have been very different without the developing administrative competence and greater coercive power of the states concerned. The Austrian military reforms of the 1740s were the result of military experience working within an increasingly effective administration, while Frederick II’s comments on the differences between Prussia and (unreformed) Austria stress the importance of administrative capacity: `I have seen small states able to maintain themselves against the greatest monarchies, when these states possessed industry and great order in their affairs. I find that large empires, fertile in abuses, are full of confusion and only are sustained by their vast resources, and the intrinsic weight of the body.’

Nevertheless, improvements in administration, better accountability, and more efficient collection and use of tax revenues would not alone have allowed Louis XIV in the early 1690s to support an army of 340,000 men and a navy of at least 30,000 sailors, any more than in 1740 would it have allowed Frederick William I of Prussia to maintain a standing army of 80,000 troops. Substantial elements of the costs of war were still met by extorting war taxes from occupied lands and from foreign subsidies such as those provided by Britain to Frederick William I. Both helped to maintain larger forces than could have been supported from native resources, but for the most part they were factors that operated only in wartime. And as the Swedes discovered to their cost in the aftermath of 1648, supporting troops at the cost of neighbouring states or through subsidies from powerful, self-interested paymasters, could involve a heavy political and military price.