Addendum

Ju 86s participating in the airlift operation:

The Ju 86s that were sent to the Eastern Front to participate in the Stalingrad airlift operation, formed KGrzbV 21 and KGrzbV 22. They were subordinated to Oberst Hans Förster, who commanded the Ju 52s at Tatsinskaya.The Ju 86 “RB+NI” piloted by KGrzbV 22’s Unteroffizier Erlbeck the first Ju 86 be lost in the Stalingrad area on December 12, 1942. This Ju 86 was shot down en route from Tatsinskaya to Pitomnik probably by 9 GIAP’s Starshiy Leytenant Arkadiy Kovachevich, who filed this “rare bird” as a “Do 215” (also a twin-boom aircraft).

The city of Stalingrad was not one of Germany’s military goals when Hitler’s Wehrmacht launched its summer offensive in Russia in June of 1942. The goal was to capture the Caucasus, which accounted for 70 percent of Russia’s oil production, and 65 percent of its natural gas. The assault on Stalingrad began on 13 September; the Russians were forced to retreat into the heart of the city, where the battle degenerated into house-to-house fighting. After a protracted period of heavy fighting within the city, the Russians launched a massive counteroffensive northwest of Stalingrad on 19 November. The Rumanian Army on the Don was shattered and retreated. The next day the Russians breached the Axis flank south of Stalingrad, threatening to encircle the Fourth Panzer and the Sixth Armies in two giant pincer movements.

Hitler organized the Army Group Don, under the command of Field Marshal von Manstein, to launch a relief effort. He asked Colonel-General Hans Jeschonnek, chief of the Luftwaffe General Staff, if the air force could assist in attempted breakout or relief operations of the Sixth Army. Jeschonnek, who apparently understood that Sixth Army’s encirclement would be a short-term situation, assured Hitler that if transport and bomber aircraft were used, and if adequate airfields inside and outside the encircled area were available, the Luftwaffe could airlift adequate supplies to the army (Hayward, 1998:235). On 22 November, the Russian pincers closed the ring near Kalach, thereby encircling Sixth Army in the land bridge between the Volga and the Don (Jukes, 1985:107). Some 250,000 German soldiers were trapped.

The re-supply effort would require the air force to deliver 750 tons of supplies per day (a figure soon reduced to 500 tons per day). Lieutenant-General Martin Fiebig, commander of Fliegerkorps VIII, the Luftwaffe corps responsible for air operations in the Stalingrad sector, warned Major-General Schmidt, Sixth Army’s chief of staff, that supplying an entire army by air was impossible, particularly when most transport aircraft were already heavily committed in North Africa. Fiebig’s superior, Colonel-General Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, agreed that the idea was infeasible, and tried to convince the German leadership that the necessary transport resources were not available (Hayward, 1998: 236). Many army and air force officers advocated that the Sixth Army attempt to break out of the Russian ring as soon as possible.

Jeschonnek quickly realized that adequate logistical support of Sixth Army by air would not be possible, even with favorable weather and no interference from the Russian air force. The standard “250kg” and “1000kg” air-supply containers on which he had based his original airlift calculations actually carried only approximately two-thirds of those loads; the weight categories were derived solely from the size of the bombs they replaced on the racks, not from the weight of the payload they could carry (Hayward, 1998: 240-1). When Jeschonnek tried to explain to Hitler that his earlier assessment had been made in haste, Hitler informed him that Reichsmarschall Goring had given his personal assurance that the air force could meet the army’s needs. In addition, Hitler had publicly announced on 8 November that he was “master of Stalingrad,” a statement that became his policy: to hold on to Stalingrad (Hayward, 1998: 215).

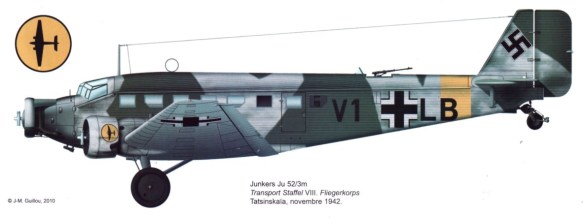

The necessary aircraft and crews for the Stalingrad airlift were assembled on short notice from the advanced flight training schools, using mostly Ju-52 and He-111 aircraft (Boog, 1978: 142). The Ju-52 carried about two and a half tons of cargo, and the He-111 could carry only two tons. Von Richthofen began airlift operations as ordered on 24 November. Approximately 320 Ju-52 and Ju-86 transports located at Tazinskaya and approximately 190 He-111 bombers at Morosovskaya were available to conduct the airlift. Neither transport type could trade much fuel for freight, because the distance from Tazinskaya to Pitomik, the main airfield at Stalingrad, was 140 miles (Whiting, 1978: 114). The primary load delivered to Stalingrad was ammunition, which the Germans desperately needed to withstand the Russian attacks. The Germans had previously agreed to slaughter and eat the horses that had carried their supplies when they first arrived in Stalingrad. But eventually even the horses were gone.

Fortunately for the Germans, the Russian air force only sporadically interfered with the airlift effort (Whiting, 1978: 113). The Russian Army continued to widen the corridor over which the German transports had to fly, and installed increasing numbers of anti-aircraft guns in it. A greater problem than the Russian aircraft and anti-aircraft fire, however, was the winter weather; the aircraft had to stand down for days, as temperatures reached 30 degrees below zero. In such appalling weather, the crews delivered only ninety-four tons daily (Mason, 1973: 367). The high point of the airlift occurred when 700 tons was delivered between 19 and 21 December—that is, 700 tons for all three days combined (Whiting, 1978: 114).

The supply airfields at Tazinskaya [24th DEC] and Morosovskaya fell into Russian hands on 22 December, increasing the distance the transports had to fly from 140 to 200 miles.

A total of 124 transport planes—108 Ju 52s and 16 Ju 86s were able to take off and escape destruction at Tatsinskaya when General-Mayor Badanov’s 24th Tank Corps reached that place in the early morning hours of December 24, 1942. At least 50 aircraft were run over by Badanov’s tank troops at Tatsinskaya – 24 Ju 86s, 22 Ju 52s, 2 I./KG 51 Ju 88s, and 2 planes from 3.(F)/10. The Soviets also captured hundreds of tons of supplies — including 300 tons of gasoline and oil, and five complete ammunition stores, according to Soviet accounts – and valuable equipment such as engine-warming wagons, and tank trucks.

Manstein gave up hope of relieving Stalingrad on 23 December (Jukes, 1985: 125). Pitomik airfield was overrun on 16 January, and the smaller auxiliary airfield at Gumrak was seized on 21 January (Whiting, 1978: 115). The Sixth Army was split into two pockets by the Russian Army, with no hope of relief or resupply. Paulus, in the southern pocket, surrendered on 31 January, but the German troops in the northern pocket held out for two more days. German radio reported the fall of Stalingrad on 3 February.

As a result of the defeat, the German Army lost enough material to equip a quarter of the German Army. There were approximately 150,000 dead, and another 90,000 taken prisoner, including 24 generals and 2,000 officers. Of these, only about 6,000 returned home. The Luftwaffe lost approximately 488 aircraft and 1,000 air crew (which includes only transport losses) during the Stalingrad airlift (Mason,1973: 367; Hayward, 1998: 310). The decision to support Stalingrad by airlift was a costly one, and it proved to be a turning point in the war.

On 14 January 1943 Pitomnik airfield was captured by the Russians. This had been a vital base for the Stalingrad airlift, so many supplies had to be parachuted in. The last 40,000 German troops surrendered on 2 February. The German losses at Stalingrad had been 110,500 killed, 50,000 wounded and 107,500 taken prisoner. The Russians lost 750,000 troops and 250,000 civilians killed. The Luftwaffe lost 266 Ju52s, 165 He111s, 42 Ju86s, 9 FW200s, 5 He177s and a single Ju290 in the air lift. KG55 lost 59 aircraft, but evacuated 9,161 troops from November to the fall of Stalingrad.

November 29 ’42 – Feb 3 ’43

Total sorties: 2,566

Effective sorties: 2,260 (91%)

Deliveries:

Provisions: 1,541.4

Ammunition: 767.50

Misc.: 99.16

Total 2,407.80 tons

Fuel in cubicm

B 4 609.07

“Otto” 459.35

Diesel 42.60

1,111.02 cubicm = 887.00 tons

Grand Total: 3,294.80 tons

Return flights of transports carried out of the pocket:

- 9,208 Officers and Other ranks

- Empty containers 2,369

- Sacks of Mail 533

From a report of Transport Command 1 commanded by Colonel Ernst Kühl. He was responsible only for He 111 formations. Ju 52 and other formations were under command of Transport Commander 2.

On November 28 3 Yak-1s of 287th fighter regiment shoot down 4 Ju 52 transports, two days later five more Ju 52s and a Me 109 are downed by the 283rd fighter division out of 17 transport planes and four Me 109 escorts. December the 2nd saw 17 transports destroyed on the ground while unloading supplies. Eight La-5s and nine Yak-1s attack 16 Ju 52s escorted by four Me 109s on December 11th scoring nine kills.

At the end 109 Ju 52s and 16 Ju 86s managed to escape from Tazi (Tatsinkaya) as shells from Soviet tanks rained down on the field. 60 wrecked transports remained at Tatsinkaya.

Total losses in this desperate attempt at supplying 6th army from the air amounted to 266 Ju 52s, 165 He 111s, 42 Ju 86s, 9 Fw 200s, seven He 177s and one Ju 290.