Siege of Enniskillen, February 1594, as drawn by John Thomas. English forces besiege a castle on the southern tip of Lough Erne held by Hugh Maguire, an ally of Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell. The siege equipment is much the same as that used seven years later at Kinsale. This picture is full of interesting details, among them Captain Dowdall’s Irish horseboy carrying his shield (centre foreground); the mobile ‘sow’ designed to cover the advance of ’30 men; the entrenched artillery positions; and the boats fitted with scaling ladders. Rowed boats continued to be important in conflict in the Western Isles of Scotland and northern Ireland in the sixteenth century, with the long-established Viking tradition of longship building continuing in the Isles. Galleys were also used by the English, as here at Enniskillen. Conflict in Ireland in the 1590s demonstrated the strength of the Irish combination of traditional irregular tactical methods with modern firearms, but also the advantages the English had when up against defensive positions.

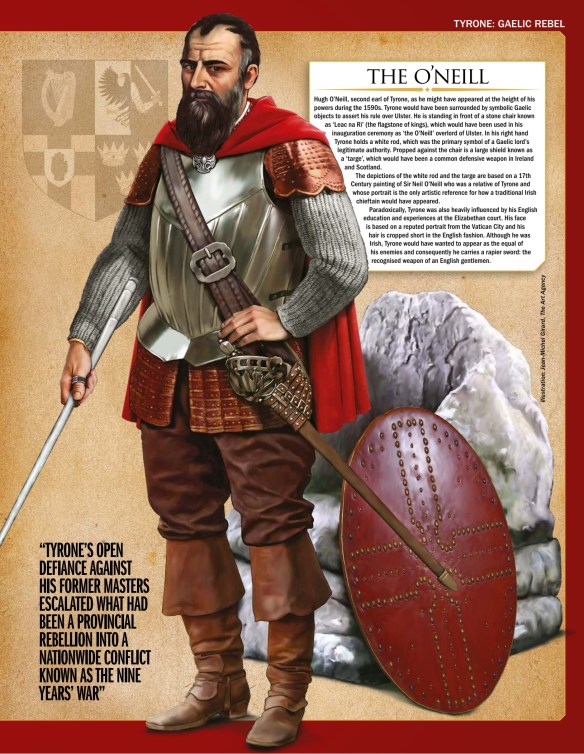

By the time war with Spain began in 1585, Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone (ca. 1550–1616), known as the Great O’Neill, the most powerful sept leader in Ulster, felt himself and his position particularly isolated and threatened by the Dublin government. Fearful of an English attack, Tyrone struck first, seizing Enniskillen in the west and Blackwater Fort in the east in the winter of 1594–5. Hugh O’Neill was a supremely canny operator – a master at wrong-footing his opponents with sleight of hand – reflected in his initially low-key campaign for the territory of Fermanagh in Ulster. When an English sheriff was imposed there in 1593, O’Neill was determined to resist – but by stealth. He fought a proxy war, pretending to be a supporter of the crown while directing a military campaign against it. When his brother Cormac defeated an English attempt to resupply its garrison at Enniskillen, Hugh absolved himself of responsibility by claiming he was unable to control his followers. Yet he was reported as arriving soon afterwards to divide up the spoils.

Knowing full well that he was in a fight for his life against a relatively wealthy and well-organized State, Tyrone sought the assistance of Old English Catholics, the pope, and the Spanish king by appealing to anti-English and anti-Protestant sentiment. At one point the rebels offered the crown of Ireland to Philip II. But many Old English remained aloof, suspecting that O’Neill intended to establish Gaelic domination. The Spanish eventually mounted an expedition in 1596, but another “Protestant wind” destroyed it. They tried again in 1597 and 1599; but each time bad weather thwarted their plans.

Still, England’s forces were already overextended in the Netherlands and France, so Elizabeth and her Privy Council first tried negotiation. Tyrone demanded much: full pardons for the rebels, de facto religious toleration, and recognition of an autonomous Ulster under O’Neill control. Rebel victories in 1598, as well as the slaughter of English settlers in Munster, made the English situation critical. The queen responded by dispatching an army of 16,000 men and 1,300 horse under the command of her favorite, the earl of Essex. As Leicester’s stepson, Essex had inherited not only the former’s standing with the queen, but also his vast clientage network. Like Leicester, he was brave and chivalrous. But he was also impulsive, prideful, and, worse – again like his stepfather – a poor general. Essex landed in the spring of 1599. Rather than take the war to Tyrone’s stronghold in the north, he wasted about £300,000 in five months marching aimlessly around the south of Ireland. In September he agreed to peace talks with Tyrone that were technically treasonous and in which the latter outmaneuvered him. Finally, when it became clear that Essex had botched the campaign, he left his army in Ireland and returned to London, without orders, in order to defend his reputation against the whispering at court. Tyrone took this opportunity to march south and burn the lands of English loyalists. The queen took the same opportunity to replace Essex in February 1600 with a much more effective soldier, Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy (1563–1606). Mountjoy eventually succeeded in suppressing the rebellion, but not before one last Spanish invasion attempt. In 1601 Philip III (1578–1621; reigned 1598–1621) sent about 3,400 crack troops to seize the southern port of Kinsale. In fact, this force was too small to help Tyrone; instead, it increased his obligations. By laying siege to Kinsale, Mountjoy drew Tyrone out from his northern stronghold and routed the Irish relief forces on Christmas Eve, 1601. The Spanish surrendered a week later. Mountjoy accepted the earl’s submission on March 30, 1603, ending this Nine Years’ War just days after Elizabeth’s death.

Much treasure and many lives had been lost in bitter guerilla warfare in the bogs of Ireland. The campaign had cost £2 million and left Ulster devastated, Munster and Cork depopulated, trade ruined, and famine stalking the land. As many as 60,000 Irish died, perhaps 30,000 English. One of Mountjoy’s lieutenants, Sir Arthur Chichester (1563–1625), summed up the devastation as follows: “we have killed, burnt and spoiled all along the lough [Lough Neagh, the largest lake in Ulster]. … We spare none of what quality or sex soever, and it have bred much terror in the people.” Mountjoy’s ruthless “pacification,” initiated on Elizabeth’s orders, was successful in its own terms, but its legacy of sorrow and bitterness further divided Irish from English and Irish from Irish.