The Manchurian Campaign

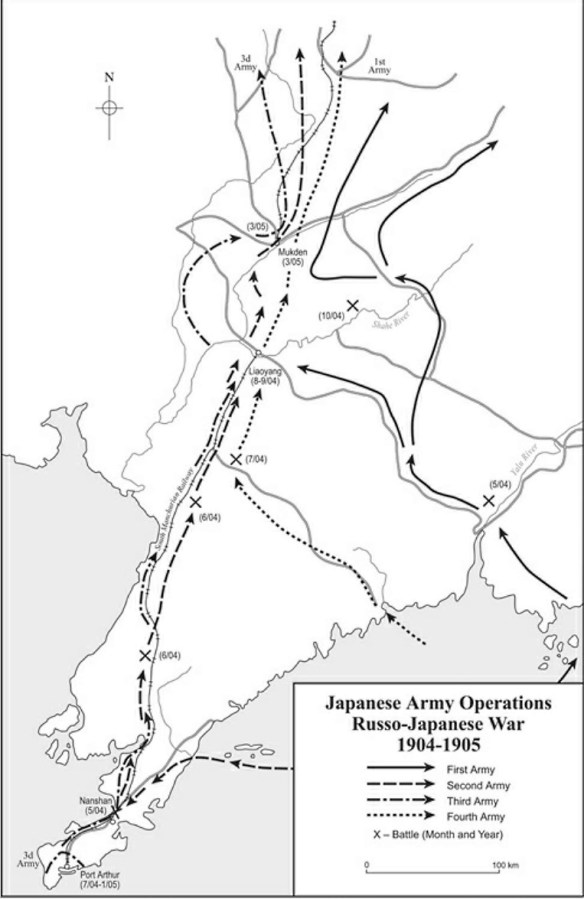

The Manchurian Army, consisting of the First and Second armies, would advance along the South Manchurian Railroad to Liaoyang, where the First Army would envelop the enemy’s right flank, destroy the Russian field army, and open the way to Mukden and the decisive battle before Russia could mobilize its full military strength. Simultaneously, the Third Army would attack Port Arthur and after taking the fortress rejoin the field armies near Mukden. The Russian commander, however, fought a series of skillful delaying actions in June and July to buy time for reinforcements to arrive from European Russia. Port Arthur was left isolated and besieged by the recently arrived Third Army.

General staff officers had not originally considered seizing the port and were unaware of the extent of Russian improvements to the fortress’s defenses. Russian military engineers had shrouded their work in tight security, and Japanese spies lacked the technical expertise to determine the strength of the improved concrete-and-steel fortifications. As a consequence, they reported that the Russians had merely extended existing trench lines, leaving the impression that Port Arthur was weakly defended as it had been during the Sino-Japanese War.

On August 19 the complexion of the war changed dramatically when the Third Army commander, Lt. Gen. Nogi Marasuke’s, ill-conceived frontal assault against Port Arthur cost at least 16,000 killed and wounded, a disaster compounded by his stubborn refusal to halt the futile attacks. A few days later Ōyama’s armies suffered more than 23,000 casualties during the seven-day battle for Liaoyang (August 25–September 3). The First Army struck the Russian center while the Second and Fourth armies turned the enemy’s eastern flank. Unable to encircle the Russians, the Japanese resorted to costly frontal attacks.

Though the army publicly glorified the efforts of the so-called human-bullets to sustain home-front morale, more responsible commanders were appalled at the needless slaughter. Junior officers blamed the “big-shot tacticians” for stubbornly applying textbook tactics that needlessly threw away soldiers’ lives. Ōyama relieved three major generals, all brigade commanders, because their inflexibility caused unnecessary casualties.

The combination of heavy losses and the inability to encircle and destroy the enemy field army shook Japanese regimental and division commanders’ self-confidence. At the height of the Liaoyang fighting, Tokyo newspaper editorials confidently predicted another Sedan, a reference to the Prussian army’s encirclement and destruction of the French army in 1870. Self-confident and certain of the outcome, the First Army’s officers and men anticipated truce talks after the battle. Morale plummeted as the realization sunk in that they faced renewed fighting. Replacements for Nogi’s Third Army at Port Arthur lost heart when battle-toughened veterans dismissed them as cannon fodder. The commander of a Guard infantry brigade wrote to the vice chief of staff that just declaring morale was high did not necessarily make it so. Discipline suffered, and the army resorted to field gendarmes to drive reluctant troops forward, at least in one case at bayonet point.

Although the army had steadily expanded from 123,000 officers and men in 1896 to 191,000 in 1903 and increased its reserves proportionately, it could not compensate for the unexpectedly high attrition during the opening engagements. These battles made clear that more troops were needed. Immediately after the Liaoyang fighting, the emperor, at IGHQ’s request, on September 29 activated four new divisions, doubled the second reserve obligation to ten years, extended the age limit for the first reserve term from 32 to 37 years old, and added forty-eight infantry battalions to the second reserve. The new provisional divisions would be organized by February 1905, but they would not be trained and ready for operations until late May at the earliest. By the time the first of the new formations was activated on April 15, 1905, the major fighting was over.

The Vladivostok naval squadron added to the overall sense of gloom and anxiety in Japan. On the morning of April 26, Russian warships surprised and sank a small Japanese ship carrying a 200-man infantry company. The soldiers refused surrender or rescue and went down with their sinking ship. Army authorities stoked patriotic home-front fires by portraying the act as a deliberate decision to avoid the shame of surrender and the debasement of captivity. Russian raiders continued to cruise the Sea of Japan, picking off victims, spreading panic among Japanese coastal towns, and provoking public criticism of the military’s incompetence.

In mid-June the Vladivostok squadron sank a large army troop transport carrying almost 2,000 soldiers and irreplaceable artillery and stores. When the admiral charged with protecting the convoy could not find the Russian warships to retaliate, angry Tokyoites stoned his house, denounced him as a Russian agent, and demanded his suicide. Wild rumors about the Vladivostok fleet terrified civilians and forced the cabinet to order an emergency reinforcement of coastal defenses in Tokyo Bay and Tsushima Island.

While the Russian squadron rampaged seemingly at will and Nogi’s Port Arthur offensive collapsed, the northern front stabilized around Liaoyang. By the end of September the army had committed three divisions to Port Arthur, sent eight to Liaoyang, and mobilized 65,000 replacements to fill the losses in its infantry divisions. In addition, field army commanders wanted the two divisions remaining in the homeland strategic reserve, but IGHQ insisted that they were needed for coastal defense against a possible Russian landing. Emperor Meiji intervened in the dispute between the field army and IGHQ by deciding that one homeland division would deploy to Liaoyang.

In early October a Russian offensive surprised the Second Army at the Shahe River, about 45 miles northeast of Liaoyang, and in the week-long battle that followed, three Japanese armies again failed to envelop the Russian flanks. Losses were heavy: more than 41,000 Russian and 20,000 Japanese fell. By this time, sickness was ravaging the field armies as beriberi, typhoid, and dysentery incapacitated thousands more troops. Ōyama halted his armies to regroup.

While Ōyama reconstituted his battered forces, imperial headquarters, reacting to the navy’s demands that Port Arthur be taken quickly, again ordered Nogi to attack the fortress. After his first setback, IGHQ had reinforced the Third Army with heavy artillery in hopes of breaching the Russian defenses. Higher headquarters grasped that artillery observers atop the dominating heights of Hill 203 could direct accurate plunging fire onto Port Arthur and its harbor, making them untenable. Nogi and his staff, however, had never been to the front lines and regarded the heights, particularly Hill 203, as secondary to the Third Army’s objective of capturing the town.

After a council with IGHQ liaison officers on September 5, the Third Army staff agreed to attack Hill 203. Assaults two weeks later seized outposts on Hill 203 but could not take the crest. Although Nogi had received reports from the front that parts of Port Arthur could be seen from recently captured hills, the full impact of this intelligence escaped him, and he suspended the offensive on September 22 after suffering 5,000 casualties.

The well-publicized struggle for Port Arthur captured world attention, and the western press popularized Nogi for its readers as the personification of the samurai warrior, who uncomplainingly endured hardship and suffering. Kodama and other senior commanders, however, were appalled by Nogi’s incompetence, which had shifted the strategic focus of the war, cost tens of thousands of unnecessary casualties, consumed vast quantities of scarce war material, and achieved nothing. The Third Army opened its third major offensive on November 26 and the next day finally captured Hill 203. The fortress and naval base were defenseless and soon surrendered. More than 59,000 Japanese casualties paid for Nogi’s victory.

In late January 1905, Russian forces tried to drive the Japanese back to Liao-yang and inflict as many casualties as possible. Fighting in bitterly cold weather near San-de-pu, the Japanese stopped the counterattack—at a cost of more than 9,000 casualties. Next followed the epic struggle from February 22 through March 10 for Mukden, a battle that pitted almost 300,000 Russians against slightly more than 200,000 Japanese. The Japanese again tried a sweeping double envelopment but could not close their pincers in time to trap the retreating Russian armies. Despite losses of 70,000 Japanese and almost 90,000 Russians, the battle was indecisive and the ground war in Manchuria was stalemated.

Tokyo misread these results. On March 11, Katsura and Terauchi proposed new offensives to Yamagata, who in turn forwarded their recommendations to Ōyama. Responding from Manchuria a few days later, Ōyama described Mukden as indeed a great victory, but he dwelled on his heavy casualties and exhausted supplies. He needed time to rebuild his logistics network and wanted the cabinet’s guidance in the form of a unified military-diplomatic policy on whether to pursue the Russians or switch to a protracted war strategy.

Ōyama’s sobering assessment convinced Yamagata and Terauchi that Japan had no means of forcing the Russians to capitulate, short of attacking Moscow or St. Petersburg, which of course was impossible. The Manchurian Army could not even attack Harbin some 250 miles away because of recent personnel losses, especially among officer ranks; ammunition shortages; logistics deficiencies; and transportation problems, including a requirement for extensive railroad construction to build a line for transporting supplies to forward units. Taking this into account, on March 23 Yamagata requested the cabinet end the war by diplomatic means.

IGHQ recalled Kodama to Tokyo at the end of March for discussions on whether to continue a protracted war or sue for peace. Kodama’s outspoken criticism of the general staff’s ineptitude peaked when he called the vice chief of staff a fool for starting a fire without knowing how to put it out. At an April 8 meeting, the senior statesmen and major cabinet ministers resigned themselves to the possibility of a protracted war unless diplomatic measures could achieve satisfactory peace terms.

In mid-October 1904 the Russian Baltic Fleet had sortied from its home port for an eight-month, 10,000-mile voyage via the Cape of Good Hope to reinforce the Russian Far Eastern squadrons and relieve Port Arthur. The adventure ended on May 27, 1905, in the Tsushima Strait, where Vice Adm. Tōgō Heihachirō’s combined fleet sank twelve first-line Russian warships and captured four more. Antiwar demonstrations erupted in Russia, where the crew of the battleship Potemkin mutinied. Internal unrest, the gloomy military situation, and the czar’s concern about a possible invasion of Sakhalin made the Russians amenable to negotiations. Japan’s leaders, aware that their armies and resources were exhausted, were likewise anxious for talks and secretly approached U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt to mediate. After a month of discussions at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, mainly about Russian refusal to consider indemnities or territorial concessions, on September 5 the Russians grudgingly agreed to cede southern Sakhalin Island to Japan. In addition, Japan received exclusive rights in Korea and control of Russian railroad lines in southern Manchuria. But there was no indemnity.

During the lead-up to war, the army appealed to an increasingly literate public and conscript force with themes of Japan’s uniqueness by virtue of the unbroken imperial line. Pamphlets subsidized by the war ministry explained in simple language that the army protected Japan from foreign threats, much like the wall around a storehouse kept wild animals or thieves from stealing treasures. Essays popularized notions that seishin and the intangible factors of battle were responsible for tiny Japan’s victory over the enormous Chinese Empire and that Japan had to fight Russia to save China from itself and prevent a collapse of the international order.

Building on that foundation, wartime propaganda had concealed Japan’s military weaknesses to manufacture an unprecedented national commitment to the war across the society. The potent combination of prewar indoctrination and wartime propaganda raised popular anticipation that shared hardships would entitle everyone to benefit from the fruits of victory. With these unrealistic expectations, the Japanese people were infuriated that the treaty contained no indemnity and doled out seemingly paltry rewards for such great sacrifices. Anti-treaty rioting and popular demonstrations erupted in Tokyo as the public directed its fury against the civilian cabinet. It might better have targeted the army.

An Assessment

Despite its extensive planning, modern weaponry, and expanded force structure, the 1904 army was still an amateurish one, characterized by regional cliques, favoritism, incompetence, and nepotism. In 1901, for example, the staff college had reorganized its curriculum to prepare officers for command of large units (brigade and higher echelon) and educate them with the latest technological principles. Instruction, however, remained rooted in tactics, and the curriculum stressed individual initiative that taught officers to command by resolute action and not get bogged down in details. Staff officers assigned to the respective armies in the Russo-Japanese War were expected to be decisive, but they lacked practical experience and tended toward doctrinaire staff college solutions, regardless of circumstances. An uncritical adherence to the norm pervaded the officer corps.

Many senior officers had made their rank and reputations as young soldiers in the restoration wars of the 1860s or the Satsuma Rebellion of the mid-1870s. Too many were autodidacts, ill prepared to encounter the rapid advances in early twentieth-century technology, military professionalism, and warfare. Nogi, for instance, a veteran of the restoration wars, the Satsuma Rebellion, and the Sino-Japanese War, was stumped when looking at a topographic map of the Port Arthur defenses. Unable to understand terrain contours or elevations, he concluded the shortest distance between two points was a straight line and ordered an attack into the most difficult and best-defended terrain, where his troops suffered enormous and unnecessary losses.

Nogi’s selection for high command also illustrated the regional biases and web of personal connections that hampered the creation of an effective professional officer corps. The army originally recalled Nogi from retirement in February 1904 to command a reserve Guard division. Two of the three serving army generals (Oku and Kuroki Tamemoto) were slated to command the First and the Second armies. The third, Sakuma Samata, had retired in October 1902 and at age 61 was judged too old to withstand the rigors of field campaigning. Yamagata then selected the 55-year-old Nogi to command the Third Army and assigned him the responsibility for Port Arthur because Nogi had captured the fortress in 1895. Nogi’s Chōshū lineage and long-standing acquaintance with Yamagata made him acceptable to the Chōshū clique that dominated the army; in addition, Nogi was on friendly terms with many senior naval officers, making him a suitable liaison for a joint campaign. But Nogi was a martinet and an aesthetic who carried his notions of a samurai code to extremes and had never psychologically recovered from losing his battle standard during the Satsuma Rebellion. Yamagata and the other generals recognized his limitations, but they still agreed that Nogi could handle what was planned as a minor secondary operation to isolate Port Arthur.

The army selected Maj. Gen. Ijichi Kōsuke as Nogi’s chief of staff. Ijichi was a superannuated artillery officer and former instructor at the staff college. He hailed from Satsuma, the cradle of many naval officers, making him acceptable to the navy and serving the army’s desire to balance its regional cliques. He was also Ōyama’s son-in-law. Though army authorities did not think much of Ijichi’s abilities, they considered him at least capable of conducting a siege. Neither Ijichi nor Nogi, however, understood modern fortifications, and Nogi’s lack of self-confidence allowed Ijichi to make operational decisions. Ijichi was incompetent, opinionated, but cautious, and he deferred to his overworked deputy, Lt. Col. Ōba Jirō, a Chōshū native, and a very aggressive personality.

In this dysfunctional headquarters, staff officers displayed little ability or initiative, leaving Ōba, an infantry officer unacquainted with siege tactics, to handle most planning. The army’s expert of fortifications and siege warfare was Maj. Gen. Uehara Yūsaku, a French-educated engineer officer. But Uehara’s father-in-law was Lt. Gen. Nozu Michitsura, the 64-year-old commander of the Fourth Army, who insisted on Uehara for his chief of staff. Unfortunately Nozu’s difficult personality made it all but impossible for anyone but his son-in-law to work with him. Personal relationships were no better in the two main armies.

Lt. Gen. Kuroki, a 60-year-old Satsuma native, commanded the First Army. He had led a division in the Sino-Japanese War, cultivated a rude and simple lifestyle, and loved good cigars. Despite appearances, he was a bookish officer, fond of history, and not a risk-taker. His chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Fujii Shigeta, was mean-spirited, nasty, and ignorant of the working of a headquarters staff. He had been the commandant of the staff college, and after it closed for the duration of the war he was assigned to Kuroki. Fujii proved inflexible, indecisive, and continually at odds with his highly talented deputy. Vice Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Nagaoka Gaishi regarded Fujii and Ijichi as equally dangerous incompetents whom the army would be better off without.

Lt. Gen. Oku Yasukata, commander of the Second Army, was barely on speaking terms with his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Ochiai Toyosaburō. A protégé of the late Tamura, Ochiai had headed the general staff’s fifth (war history) department and served as an instructor at the staff college. He had a flair for map maneuvers and tabletop tactics, but in actual operations he proved stubborn, inflexible, and ignorant of logistics as well as rear area security requirements. Ochiai handpicked his subordinates from the ranks of staff college instructors, and, like their mentor, they were fixated on map exercises and theory, unable to adapt swiftly to rapidly changing battlefield conditions of real warfare.

Intelligence collection and analysis was also personality-driven and idiosyncratic. Maj. Gen. Fukushima was the chief of the intelligence department of the general staff. Col. Matsukawa Toshitane, an infantry officer and director of the first (operations) department, however, relied on his own intelligence sources, splitting the general staff into fiercely competitive Matsukawa and Fukushima factions. The general staff’s arrogance so alienated the foreign ministry that diplomats refused to share the intelligence that they gathered in the United States or Europe, leaving the army without strategic data regarding domestic unrest in Russia, manipulation of radical elements there, or the Port Arthur defenses. At the operational level, officers treated intelligence casually because the top graduates of the staff college invariably went into combat arms—infantry, artillery, cavalry—and were taught to and preferred to make their own assessments.

Operational intelligence repeatedly ignored inconvenient discoveries that might disrupt planning already in progress. After the Liaoyang battle, the long-serving military attaché in London, Lt. Col. Utsunomiya Tarō, received intelligence from British sources that the Russian Second Army was about to counterattack the Japanese right flank. Imperial General Headquarters decided that the Russians could not move large formations through the rugged, mountainous terrain and did not pass on the warning. Oku was thus surprised on October 5 when the Russians struck his exposed right flank to open the Battle of Shahe.

In mid-January 1905 Utsunomiya and the military attaché to Berlin, Lt. Col. Ōi Shigemoto, reported that Russians planned to attack the left flank of Ōyama’s Manchurian Army along the Shahe River. Manchurian Army staff officers insisted that the bitter cold and deep snow made a major offensive impossible. When eight Russian divisions attacked in the middle of a late January snowstorm, Ōyama’s headquarters dismissed the offensive as a minor reconnaissance-in-force.

The displacement of IGHQ to Hiroshima a decade earlier had been disruptive because the government ministries remained in Tokyo, requiring extensive and expensive coordination that resulted in frequent delays. This time the emperor stayed in Tokyo to coordinate civil government as well as military affairs. Senior officers then complained that IGHQ was too far removed from the front lines to act as an operational headquarters, and in March 1904 Vice Chief of Staff Kodama suggested a supreme command headed by a crown prince be established in Manchuria.

Ōyama, the newly appointed commander of the field armies in Manchuria, insisted on total control of the overseas forces, including logistics and personnel matters. War Minister Terauchi rejected the general staff’s proposal to grant Ōyama such sweeping authority because it would turn IGHQ into a cipher. Furthermore, Terauchi and Prime Minister Katsura—the latter acting as a general, not as the prime minister—wanted IGHQ to coordinate the joint campaign against Port Arthur directly from Tokyo. Based on Yamagata’s counsel, on May 25 the emperor instructed Terauchi and Ōyama to establish a senior field headquarters to command Manchurian armies and gave Ōyama operational control of the field forces.

On June 20, the war ministry activated the Manchurian Army Headquarters, appointed Ōyama as supreme commander, promoted Kodama to general, and reassigned him as Ōyama’s chief of staff. Yamagata became chief of staff (rear) with control of logistics, personnel, and administrative matters at IGHQ; Nagaoka Gaishi was the vice chief of staff (rear). The brightest young officers were assigned to the Manchurian Army while recalled officers or senior statesmen staffed Imperial General Headquarters. Friction quickly developed between the Manchurian Army and IGHQ, especially over the development of the Port Arthur campaign, the deployment of strategic homeland reserves to Manchuria, and the mobilization of new divisions.

Dysfunctional personalities, a cumbersome command-and-control network, and a poorly integrated imperial headquarters exacerbated the army’s fundamental problem: it was essentially refighting its last war, having projected casualty rates, ammunition consumption, and logistics requirements based on its Sino-Japanese War experience.

After driving the Russians from Nanshan, IGHQ expected to systematically isolate Port Arthur, causing it to fall. As mentioned, the second department’s outdated intelligence underestimated the much-improved fortress defenses that skillfully blended formidable new strong points into the hilly topography. Based on shopworn intelligence, in late February 1904 Maj. Ōba Jirō and Maj. Tanaka Giichi (both then concurrently general staff and IGHQ staff officers), among others, recommended seizing the seemingly weak fortress before reinforcements arrived from western Russia. Kodama wanted to keep his armies intact and thought it better to isolate Port Arthur rather than storm it. Once the navy closed the harbor entrance, the Russians would be isolated and the Third Army could prevent the garrison from threatening the First Army’s rear areas. Port Arthur would wither on the vine.

Because the navy failed to close the harbor, it had to blockade Port Arthur and patrol the nearby waters to prevent the escape of the Russian naval squadron. Put differently, the Russian fleet-in-being at Port Arthur tied down a goodly part of the combined fleet. To unleash the fleet, the navy pressed IGHQ to order the army to capture the fortress, which would also neutralize the Russian fleet. Under mounting pressure from the navy, on June 24 IGHQ ordered Nogi to attack Port Arthur as soon as possible. A few weeks later, intelligence reported that the Russian Baltic fleet was making preparations to sortie. Tōgō then requested via the naval chief of staff on July 12 that the army attack Port Arthur without delay to allow the navy the time it needed to refit before arrival of the Baltic fleet. Whatever Nogi’s faults—and they were many—he was the only field commander subjected to repeated operational interference by Imperial General Headquarters and the navy.

IGHQ hoped to avoid a frontal attack by maneuvering the Third Army farther west to take the fortress from the rear. Nogi and his staff complained that repositioning the troops and artillery would take too much time and pull the Third Army farther from its railhead supply point. He understood his mission was to capture the city, not the defensive outposts on the high ground overlooking it, and, as mentioned, was unable to read topographic maps so chose the shortest direct route to Port Arthur.

A two-day bombardment by Nogi’s light artillery did not seriously damage the concrete-and-steel–reinforced bunkers. Russian machine-gun crews secure inside their fortifications raked the massed attackers, who became snarled in barbed-wire entanglements. Faulty intelligence that the Russian line had broken prompted Nogi to renew the costly attacks. By the time he called off the assaults, the Third Army had suffered almost 16,000 casualties, including more than 5,000 killed in action. An Osaka-based regiment refused to attack after suffering heavy losses and was escorted to the rear under guard.

Losses among officers were extremely heavy because tactical commanders followed their training and led from the front. The 44th Infantry Regiment, for instance, had two of its three battalion commanders killed and the third wounded; it lost all twelve of its company commanders, eight killed and four wounded; and thirty-five of forty lieutenants were killed or wounded. Nogi’s losses and the subsequent 23,000 casualties suffered at Liaoyang precipitated a chronic replacement crisis that was exacerbated by the lack of tactical skills and leadership ability among many replacement reserve officers and NCOs.

Government authorities tried to conceal the magnitude of Nogi’s defeat through a combination of strict censorship, tight restrictions on war correspondents, and control of battlefield news releases. Army service regulations issued in January 1904 to protect military secrets complemented home ministry restrictions on newspaper articles enacted the previous year to stifle dissent. Police censors paid special attention to articles that they thought might lower the morale of soldiers’ families.

At the opening of the Russo-Japanese War, the government mobilized patriotic associations to organize nationwide relief campaigns to assist families of soldiers serving overseas and send troops small packages of sundries. Officials also diverted public attention from battlefield realities by publicizing real or imagined heroism and tales of glorious death in battle. Official propaganda unintentionally inflated popular expectations, working the public into a patriotic fervor that backfired when unrealistic goals could not be met. For instance, in August the government-sponsored preparations were under way nationwide to celebrate the anticipated fall of Port Arthur, but popular enthusiasm soon waned when victory was not forthcoming. After another Tokyo pro-war rally degenerated into a brawl that left thirty-nine people dead or injured, even “spontaneous” victory parades fell under greater police scrutiny.

Despite government and army propaganda, Nogi too fell under a cloud of growing criticism. Irate citizens denounced him as a butcher, stoned his home, and threatened his wife. Nor could the government’s upbeat official version of events conceal the grievous losses from the Japanese public. Hospital trains departed nightly from Ujina, and by mid-September the sight of caravans of wounded soldiers passing through the Tokyo streets to hospitals was commonplace. Letters from frontline soldiers and stories from replacements reached home with tales of heavy casualties, widespread illness, and war weariness. Inflation, numerous new special taxes on land and consumables to pay for the war, the continual reserve mobilizations of replacements, and rumors of terrible casualties weighed heavily on popular morale.