William of Normandy’s own history to some extent mirrored that of his elder cousin in England, Edward the Confessor. Like Edward, William had been orphaned at an early age. His father, Robert of Normandy, had died in 1035, returning from a penitential pilgrimage to the Holy Land, when William was only seven or eight. Like Edward, William was dependent during his youth upon much older and more powerful men. Like Edward, William clearly suffered his own share of indignities, not least the murder of some of his closest counsellors in the ducal court, acts of public violence which suggest, like the murder in England of Edward’s brother or the upheavals of 1051–2, not only a society loosely governed under the law, but one in which the ruler struggled hard and often ineffectively to make his rulings stick. Such was the fear of assassination that William himself had to be hidden by night in the cottages of the poor, to escape the plots of his enemies.

Here, however, the comparisons between England and Normandy end and the contrasts begin to assert themselves. The rulers of Normandy, like those of England, exercised the same late-Roman proofs of public authority: for example, jurisdiction over roads, public crimes such as murder, rape or arson, the minting of coins and the disposal of treasure. Even today, much of the authority invested in the person of Queen Elizabeth II – over the Queen’s highway, treasure trove, the Queen’s counsels and the law courts in which they act, the royal mint – derives from far more ancient precedents than the Roman emperors or even the rulers of ancient Babylon might have recognized as specifically ‘royal’ prerogatives. Yet, in the eleventh century, there was a considerable contrast between Normandy and England, both between the extent to which such prerogatives were exercised and between the instruments by which they were imposed.

Normandy could boast nothing like the wealth of England. The English coinage, for example, with its high silver content, stamped with a portrait of the reigning English King, regularly renewed and reminted as part of a royal and national control over the money supply, has to be contrasted with the crude, debased and locally controlled coinage of pre-Conquest Normandy, at best stamped with a cross, at worst resembling the crudest form of base-metal tokens, the sort of token that we would use in a coffee machine rather than prize as treasure. In Normandy, the dukes had local officials, named ‘baillis’ or bailiffs, but nothing quite like the division of England into shires, each placed under a shire-reeve in theory answerable to the King for the exercise of royal authority through the meetings of the shire moot, the origins of the later county courts. In particular, whilst in England kings communicated directly with the shire by written instruments, known as writs, instructing that such and such an estate be granted to such a such a person, or that justice be done to X or Y in respect of their claims to land or rights, there is no evidence that the dukes of Normandy enjoyed anything like this sort of day-to-day control of local affairs. Not until the twelfth century were writs properly introduced to the duchy, fifty or more years after the Conquest and in deliberate imitation of more ancient English practice. Norman law itself was for the most part not customized or written down into law codes until at least the twelfth century. Above all, perhaps, the dukes of Normandy were not kings. Although they underwent a ceremony of investiture presided over by the Church, intended to emphasize their divinely appointed authority, they were not anointed with holy oil or granted unction as were the kings of England, raising kings but not dukes to the status of the priesthood and transforming them into divinely appointed ministers of God. The Bayeux Tapestry shows William of Normandy wielding the sword of justice, sometimes seated upon a throne, sometimes riding armed into battle. By contrast, both in the Tapestry and on his own two-sided seal, Edward the Confessor is invariably shown seated, enthroned, carrying not the sword but the orb and sceptre, far more potent symbols of earthly rule. William had to do his own fighting. Edward the Confessor, as an anointed king, had others to fight for him.

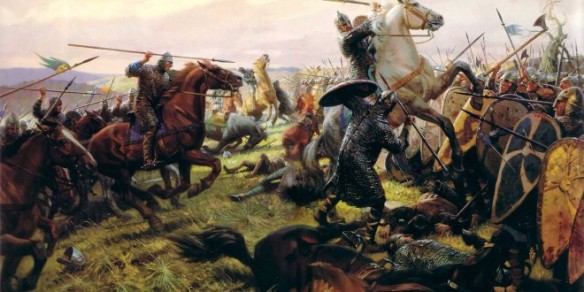

Thus far, the contrasts between England and Normandy seem all to be to the advantage of England, a much-governed and more ancient kingdom. Yet there is another side to the story. Precisely because they were newcomers, parvenus, risen from the dregs of a Viking pirate army, the heirs of Rollo were spared much of the dead weight of tradition that tended to gather around any long-established dynasty. To take only the most obvious example here, in England no king could afford to ignore the established power of the great earldoms of Mercia, Wessex and Northumbria. Earls were in theory the appointed delegates of the King. In practice, when Edward the Confessor attempted to appoint his own men to earldoms – Ralph of Mantes to Herefordshire, Odda of Deerhurst to western Wessex, Tostig to Northumbria – the fury of local reaction was such that these appointments were either swiftly revoked or risked head-on confrontation with local interests. Normandy had a secular aristocracy, but it was one that had emerged much later, for the most part in direct association with the ruling dynasty, in most instances from the younger sons and cousins of the ducal family. By the 1050s, under William, most of the higher Norman aristocracy were the duke’s own cousins or half-brothers. This tended to intensify the rivalries within a single, all powerful family, and William faced far fiercer and more frequent rebellions against his rule than ever Edward the Confessor faced from the English earls. Yet the very ferocity of this competition tended to focus attention and an aura of authority upon William himself as successful occupant of the ducal throne. The more fighting there is over a title, the greater the authority that such a title tends to acquire. From both of the great crises of his reign, in 1046 when there was concerted rebellion against his rule in western Normandy, and again after 1051, when the malcontents within Normandy threatened to make common cause with outside forces including the counts of Anjou and the King of France, William emerged victorious. At the battles of Val-ès-Dunes in 1047, Mortemer in 1054, and Varaville in 1057, he himself triumphed over his enemies, in the process gaining not just an aura of invincibility but significant practical experience of warfare. Edward the Confessor, by contrast, for all his fury and petulance, had never fought a battle and emerged in 1052 from the one great political crisis of his reign with his authority dented rather than enhanced. There was no Norman equivalent to the Godwins, threatening to eclipse the authority of the throne.

William of Normandy enjoyed distinct advantages, not only in respect of the secular aristocracy, but in his dealings with the Church. In England kings were anointed as Christ’s representatives on earth. Patronage of the greater monasteries and the appointment of bishops were both distinctly royal preserves. King and Church, Christian rule and nationhood had become indivisibly linked. Even in his own lifetime, Edward was being groomed for sanctity. As early as the 1030s, there is evidence that the King, by simple virtue of his royal birth, was deemed capable of working miracles and in particular of touching for the king’s evil (healing scrofula, a disfiguring glandular form of tuberculosis, merely by the laying on of his royal hands). There was nothing like this in Normandy. William, as contemporaries were only too keen to recall, was descended from ancestors who had still been pagans almost within living memory. Ducal patronage of the Church was itself a fairly recent phenomenon: William’s tenth-century ancestors had done more to loot than to build up the Norman Church. And, yet, in the century before 1066, it was this same ducal family that went on to ‘get religion’ and in the process refound or rebuild an extraordinary number of the monasteries of Normandy, previously allowed to collapse as a result of Viking raids.

They also introduced new forms of the monastic life, above all through their patronage of outsiders: men such as John of Fécamp who wrote spiritual treatises for the widow of the late Holy Roman Emperor, and the Italian Lanfranc of Pavia, one of the towering geniuses of the medieval Church, first a schoolmaster in the Loire valley, later prior of Bec and abbot of St-Etienne at Caen in Normandy, promoted in 1070 as the first Norman archbishop of Canterbury.

In England, the West Saxon kings might have their own royal foundations and their own close contacts with monasteries such as the three great abbey churches of Winchester, or Edward’s own Westminster Abbey, but members of the ruling dynasty were not promoted within the church. To become a bishop, a man had first to accept the tonsure, the ritual shaving of a small patch of scalp. Perhaps because the tonsure was associated with the abandonment of throne-worthiness (in the Frankish kingdoms it had been the traditional means, more popular even than blinding or castration, of rendering members of the ruling dynasty ineligible for the throne), there is little sign that any West Saxon prince was prepared to accept it.

In Normandy, by contrast, William not only patronized the church and founded new monasteries, but promoted members of his own family as bishops. At Rouen, for example, the ecclesiastical capital of the duchy, Archbishop Robert II (989–1037), son of Richard I, Duke of Normandy, and founder of a dynasty of counts of Evreux, was succeeded by his nephew, Archbishop Mauger (1037–54), himself son of Duke Richard II. William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Odo, was promoted both as bishop of Bayeux, in all likelihood future commissioner of the Bayeux Tapestry, and as a major figure in ducal administration. As the Tapestry shows us, not only did Odo bless the Norman army before Hastings, but he rode into the battle in full chain mail. For priests to shed blood was regarded as contrary to their order. Odo therefore went to war brandishing not a sword or spear but a still very ferocious looking club. The Tapestry shows him at the height of battle, as its contemporary inscription tells us ‘urging on the lads’. In the aftermath, Odo was appointed Earl of Kent. His seal showed him on one side as a bishop, standing in traditional posture, tonsured, dressed in pontifical robes and carrying a crozier. On the other side, however, he is shown as a mounted knight riding into battle with helmet, lance and shield, unique proof of the position that he occupied, halfway between the worlds of butchery and prayer.

William himself might not have been anointed as Duke of Normandy, but in the eyes of the Church he commanded perhaps an authority not far short of that wielded by the saintly Edward the Confessor. In particular, the fierce penitential regime of William and his father lent an aura of religiosity to what might otherwise be construed as their purely secular acts of territorial conquest. William’s father, Duke Robert, died whilst returning from a penitential pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the ne plus ultra for anyone concerned to advertise their Christian piety and remorse. Jerusalem at this time, of course, was still firmly under Islamic rule. To visit it, and to walk in the places where Christ had trod, was both an arduous and an expensive undertaking. William himself, by marrying his own cousin, Matilda of Flanders (thereby forging an alliance with the greatest of the magnates on Normandy’s northern frontier), was obliged to undergo penance by the Church. It was penance, however, that both broadcast a particularly powerful image of the duke himself and paved the way for further acts of territorial expansion. To atone for his sins, William built the massive Benedictine monastery of St-Etienne at Caen. Matilda, at the same time, paid for the construction of a sister house, a no less massive monument on the other side of Caen, intended for nuns, the abbey of La Trinité. In the space between these two great monasteries, William laid out a vast ducal castle, surrounded by ramparts, the whole complex of abbeys and castle itself surrounded by a new town wall. As an advertisement of ducal power, the planning and construction of Caen took place on a truly epic scale. To lead his new abbey, William promoted the outsider Lanfranc: a clear bid to demonstrate his commitment to the reforming party within the Church as a whole, and a means of strengthening ties between Normandy and the reforming Church in Rome.

By the 1060s, the Norman Church basked in papal approval. The English Church, however, became ever further severed from continental tendencies, not least through the promotion by Queen Edith of Stigand, Bishop of Winchester and a member of the Godwin affinity, as Archbishop of Canterbury. Thereafter he ruled both Canterbury and Winchester as a pluralist, against the dictates of the Church, and, more seriously still, blessed as archbishop of Canterbury not by the rightful pope of the reforming party but by a rival, whom the Roman aristocracy had briefly established on the papal throne. In the eye of the papacy, Stigand was a scandal. William of Normandy, by contrast, was later to claim that his invasion of England was undertaken as a holy war, intended to cleanse the polluted Anglo-Saxon Church and to bring enlightenment to a nation sunk in sin. The Pope, Alexander II, certainly sent William a banner, as a token of friendship and special favour. Whether Alexander realized that William would use this banner to lead his men in the conquest and slaughter of fellow Christians across the English Channel is another matter entirely. The banner, like William’s close relations with Rome, was a powerful tool of propaganda. Propaganda itself, however, does not necessarily accord with ‘truth’.

Preparations for Invasion

In Normandy, meanwhile, the preparations for invasion involved an immense expense of money and effort. Alliances with other French lords had to be negotiated to secure an army sufficient to the task. One modern commentator has calculated that an army the size of William’s represented a logistic miracle. Allowing for 10–15,000 men, and 2–3,000 horses, the force that waited throughout August and early September on the estuary of the river Dives to the north of Caen would have consumed a phenomenal quantity of grain and other foodstuffs. Had the troops slept in tents, then these alone would have required the hides of 36,000 calves and the labour of countless tanners and leather workers. The horses would have produced 700,000 gallons of urine and 5 million tons of dung. We seem to be back in the world of the tannery, far from the more exalted claims that were advanced on William’s behalf and a long way from the shadow of the papal banner under which William’s army is supposed to have marched. Even if we treat these figures as inflated or wildly speculative, the sheer scale of the operation cannot be ignored. That there was indeed an epic quality to William’s preparations is suggested by the Life of William by William of Poitiers, which deliberately echoes the words of both Julius Caesar and Virgil in its account of William’s Channel crossing, here likened to the expedition of Caesar to conquer Britain, and to Aeneas’ flight from Troy to Rome, to the foundation of a new world order.

An even more ancient myth may have been present in William’s own mind. In June 1066, shortly before embarking for England, William had offered his own infant daughter, Cecilia, as a nun at the newly dedicated abbey of La Trinité, Caen. Was he thinking here, perhaps, of the sacrifice of a daughter by an earlier king, by Agamemnon of his daughter Iphigenia, intended to supplicate the Greeks and hence to supply a wind to speed the Greek expedition against Troy? If so, then by associating himself with the Greeks, outraged by the abduction of Helen, William not only broadcast his own sense of injury against the treacherous King Harold but trumped even Virgil in his appeal to classical mythology. Aeneas had founded Rome as an exile from ravaged Troy. William would be the new Agamemnon, precursor to the exploits of Alexander, fit conqueror not just of Troy or Rome but of the entire known world.

Medieval rulers were rarely blind to the classical footsteps in which they trod, or blithely unconscious of the epic nature of their deeds, and the Norman Conquest of England was certainly an expedition of epic scale. Having mustered his army in early summer, and camped at the mouth of the river Dives for over a month, presumably on the river’s now vanished inland gulf, protected from attack by sea, some say waiting for a wind, others for news that Harold’s fleet had dispersed or been diverted northwards, William moved his army to St-Valéry on the Somme and from there set sail on the evening of 27 September, hoping that a night-time crossing would enable his fleet to slip past whatever English force was waiting for them in the Channel. Once again, it was surely no mere coincidence that his landing at Pevensey took place on 28 September, the vigil of the feast day of Michaelmas, commemorating the same warrior Saint Michael, the scourge of Satan, whom Edward the Confessor had honoured thirty years before, while in exile in Normandy, in the hope of Norman support to secure him the English throne.

The Normans in England

The ensuing campaign, in so far as there was one, can be briefly told. William immediately embarked on a scorched-earth policy, harrying and foraging as was the general rule for medieval warfare, burning villages, terrorizing the local population, advertising his own position and at the same time assembling the sort of resources in food and provender that would be required to maintain his vast army should the enemy refuse immediately to engage. The harvest was newly gathered in, so resources were not hard to find. But the prospects, if the English held back, were not propitious. A Norman occupation of Sussex might dent Harold’s pride, not least because his own family stemmed from precisely that part of England, but would not in itself have delivered a fatal blow to the English state. By contrast, the chances that William’s army could be held together for any period of time without proper supplies and without engaging the enemy, were slim indeed. Even the greatest warriors have to eat, and no lord in the eleventh century could afford to leave his own estates unprotected for long, especially at harvest time when the pickings were richest. The Norman army was now in entirely foreign territory. Very few, even of its leaders, had any experience of England. Without the benefit of Ordnance Survey maps or signposts, they would have depended entirely upon local spies and intelligence-gathering, but the local people no more spoke French than William’s soldiers could read Anglo-Saxon.

William moved east towards Hastings, building a temporary castle at Hastings itself, positioning his own army across the main road to London. Hastings was already a major centre of English naval operations, and its occupation was to some extent equivalent to the later seventeenth-century Dutch burning of the Medway dockyards. But this in itself was not sufficient to provoke Harold to battle. Rather, hubris persuaded Harold, having just marched his army southwards from Yorkshire, to leave the safety of London and immediately embark upon another campaign, risking the third pitched battle in three weeks. Perhaps precisely because battle was so rare, and because Stamford Bridge had proved so total a victory, Harold, the experienced commander of more than a decade of warfare in Wales, believed himself invincible.

Myths of the Conquest

The first is that mercenaries or knights serving for money fees played no real role in English military organization prior to the late thirteenth century. On the contrary, not only were large numbers of mercenaries maintained even for William of Normandy’s army of conquest in 1066, but thereafter the mercenary was a standing feature of most armies. A list of the payments made from the household of William de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, as early as the 1180s, records a whole series of money fees paid as annual retainers to unlanded knights, conveniently divided between those attached to the earl’s household either in England or in France, supplying yet further proof of the tendency, within a century of the Conquest, for the two parts of the Norman empire to go their own separate ways. Secondly, although, after 1066, the baronial honour and its court served as a significant instrument of social control, and although, on a local scale, such courts functioned in many ways as royal courts in miniature, we should not exaggerate either their cohesion or their sense of group loyalty. Once a generation had passed, the original loyalties upon which they had been formed soon dissolved in forgetfulness and changeability. Like all revolutions, the Norman Conquest of 1066 did not establish an unchanging social order of its own. On the contrary, it led inexorably towards yet further and more profound social change.