The rulers of the western delta city of Sais were the great survivors of ancient Egyptian history. Over the course of two centuries, they plotted, schemed, and muscled their way into a position of dominance, not just in their Lower Egyptian homeland but throughout the Nile Valley. Starting with the prince of the west, Tefnakht, in 728, the canny Saites had refused to kowtow to a rival dynasty from Nubia and had remained a thorn in the side of the Kushites for seventy years. They had then used Assyrian protection to widen their power base in the delta, finally throwing off their vassal status and claiming the prize of a united monarchy. As the ruling dynasty of Egypt, they had proved equally astute, siding with the Assyrians to counter the mutual threat from Babylonia. Honoring the native gods while buying the support of Greek mercenaries, the house of Psamtek succeeded in maintaining Egypt’s status and independence in an increasingly uncertain world.

But even the Saites were not invincible. Within a decade of repelling a Babylonian invasion, they found themselves facing an even more determined and implacable foe—an enemy that seemed to come out of nowhere.

In 559, a vigorous young man named Kurash (better known as Cyrus) acceeded to the throne of an obscure, insignificant, and distant land called Persia, then a vassal of the powerful Median Empire. Cyrus, however, had ambitions and soon rebelled against his overlord, dethroning him and claiming Media for himself. The Egyptian pharaoh showed little interest in all of this. It was a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom he knew nothing. Yet Egypt would come to rue its complacency. Within two decades of coming to power, Cyrus had conquered first the Anatolian kingdom of Lydia and then Babylonia, to become the undisputed ruler of an empire stretching from the shores of the Aegean to the mountains of the Hindu Kush. Suddenly, out of the blue, there was a frightening new superpower in the region with a seemingly relentless appetite for conquest.

All Ahmose II could do was hire more Greek mercenaries, build up his naval forces, and hope for the best. Cyrus’s death in 530, while fighting the fierce Scythian nomads of Central Asia, seemed to offer a glimmer of hope. However, any thought of a reprieve was swiftly dashed by events in Egypt itself. King Ahmose, with his army background and strategic ability, had successfully held the line for four decades. So his demise in 526 and the accession of a new, untried, and untested pharaoh, Psamtek III (526–525), dealt the country a blow. The death of a monarch was always a time of vulnerability, but with an aggressor on the doorstep, it was nothing short of a disaster for Egypt.

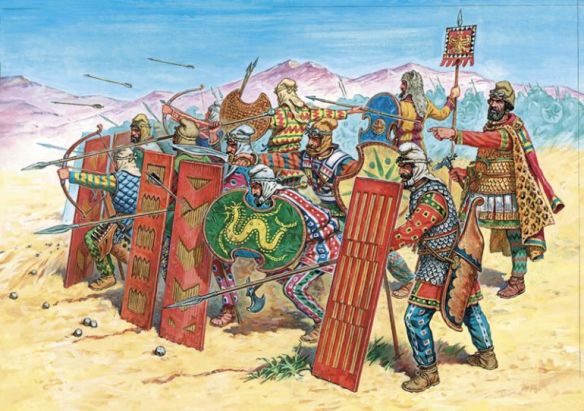

The new great king of Persia, Cambyses, saw an opportunity and seized it. Within weeks of receiving the news of Ahmose’s death, he was on the march and heading for the delta. In 525, his forces invaded Egypt, captured Memphis, executed Psamtek III, and forcibly incorporated the Two Lands into the growing Persian realm.

Cambyses lost no time in imposing Persian-style rule on his latest dominion. He abolished the office of god’s wife of Amun, denying Ahmose’s daughter her inheritance and pushing aside the incumbent god’s wife of Amun, Ankhnesneferibra, who had been in office for a remarkable sixty years. There would be no more god’s wives to act as a focus for native Egyptian sentiment in Upper Egypt. Not that every Egyptian official saw the Persian takeover as a calamity. Some found it only too easy to change allegiance when faced with the new reality. One such was the overseer of works Khnemibra. Coming from a long line of architects that stretched back 750 years to the reign of Ramesses II, Khnemibra—like his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather before him—bore an overtly loyalist name (in his case the throne name of Ahmose II), and he had served his pharaoh faithfully in the quarries of the Wadi Hammamat. But for all his professed loyalty to the Saite Dynasty, he showed no hesitation in accommodating himself to the Persian invasion. He not only survived the change of regime, he prospered, continuing to serve his new Persian masters and being rewarded for his trouble with a clutch of lucrative priestly offices. For many like Khnemibra, personal advancement trumped patriotism every time.

Others may have had slightly more altruistic reasons for collaborating with the Persians. For the Egyptian elite, nothing embodied their cherished culture and traditions better than their religion. Indeed, every prominent member of society took pains to demonstrate his piety to his town cult, and active patronage of the local temple was a prerequisite for winning respect in one’s community. When faced with alien conquerors who worshipped strange gods, some Egyptians decided not to fight but to try to win the Persians over—to the Egyptian way of doing things.

A native of Sais, proudest of delta cities, managed to do just that. Wedjahorresnet had all the right credentials. His father had been a priest in the local temple, and Wedjahorresnet had grown up with a deep devotion to the goddess Neith. Like many a Saite before him, he had pursued a career in the military, rising to the position of admiral under Ahmose II. His naval activities must have included sea battles against the invading Persians. He described the invasion as a “great disaster … the like of which had never happened in this land [before].” Yet within months of Cambyses’s victory, Wedjahorresnet had ingratiated himself with his new master, winning trust as a senior courtier and being appointed as the king’s chief physician, with intimate access to the royal presence. In public, Wedjahorresnet’s conversion was as thorough as it was rapid, and he showed no trace of embarrassment in lauding the Persian invasion in glowing terms:

The great leader of all foreign lands, Cambyses, came to Egypt, the foreigners of all foreign lands with him. When he had assumed rule over this land throughout its length, they settled there and he became great ruler of Egypt, the great ruler of all foreign lands.

Yet there was more than simple collaboration behind this astonishing volte-face. With his knowledge of Egyptian customs, Wedjahorresnet was in a unique position to guide the country’s new Persian masters and begin the process of Egyptianization, which would turn them into respectable, even legitimate, pharaohs. An important step in this process was the composition of a royal titulary for Cambyses, which Wedjahorresnet masterminded and no doubt strongly encouraged. Little by little, slowly but surely, the Persians were acculturated, following in the footsteps of previous foreign dynasties—Hyksos, Libyan, and Kushite.

Cambyses seems to have acquiesced to the process. With his vast and polyglot empire, he could ill afford to take a culturally purist view. Instead, he showed great tolerance for the different cultures and traditions within his realm. His predecessor Cyrus had released the Jews from their exile in Babylon, and Cambyses followed suit, protecting the large Jewish community in Egypt on the island of Abu. Elsewhere in the Nile Valley, he was perfectly willing to retain the services of Egyptian officials, and life for many people, especially in the provinces, continued much as before. Only in the military were Egyptian officers replaced and their leadership skills directed anew, as with Wedjahorresnet.

Having been forced to relinquish his naval command, the erstwhile admiral turned his talents to safeguarding and honoring his local temple. His position at court gave him special influence, and he set about using it to further the cult of Neith at Sais. First, he complained to Cambyses about the “foreigners” who had desecrated the temple by installing themselves inside its sacred precinct, and he persuaded his master to issue an eviction notice. After further lobbying, Cambyses ordered the temple to be purified, and its priesthood and offerings reinstated, just as they had been before the Persian invasion. As Wedjahorresnet explained, “His Majesty did these things because I caused His Majesty to understand the importance of Sais.” To set the seal on this “conversion,” Cambyses paid a personal visit to the temple and kissed the ground before the statue of Neith, “as every king does.” The Persian conqueror was well on the way to becoming a proper pharaoh.

The same pattern was followed at sites throughout Egypt. In the delta city of Taremu, the local bigwig Nesmahes used his influence—he was overseer of the royal harem—to enrich his community and its cult. It may have helped that the Persian kings readily identified with the power of the local lion god, Mahes, but, here as elsewhere, the determination of Egyptian officials to convert their new masters was a key factor behind developments in the First Persian Period. At Memphis, burials of the sacred Apis bulls continued without interruption, and the Egyptian responsible for the cult could even boast of proselytizing the country’s new rulers: “I put fear of you [Apis] in the hearts of all people and foreigners of every foreign land who were in Egypt.”

The Egyptians might have lost their political independence, but they were determined to maintain their cherished cultural traditions.