In 1806 Prussia’s foreign policy dilemma remained unsolved. ‘Your Majesty,’ Hardenberg warned in a memorandum of June 1806, ‘has been placed in the singular position of being simultaneously allied with both Russia and France [… ] This situation cannot last.’ In July and August feelers were put out to the other north German states with a view to establishing an inter-territorial union; the most important fruit of these efforts was an alliance with Saxony. But the negotiations with Russia advanced more slowly, partly because of the sobering effect of the still-recent disaster at Austerlitz and partly because it took time for the confusion generated by the months of secret diplomacy to clear. Little had thus been done to build a solid coalition when news reached Berlin of a further French provocation. In August 1806, intercepts revealed that Napoleon was engaged in alliance negotiations with Britain, and had unilaterally offered the return of Hanover as an inducement to London. This was an outrage too far. Nothing could better have demonstrated Napoleon’s contempt for the north German neutrality zone and the place of Prussia within it.

By this point, Frederick William III was under immense pressure from elements within his own entourage to opt for war with France. On 2 September, a memorandum was passed to the king criticizing his policy thus far and pressing for war. Among the signatories were Prince Louis Ferdinand, popular military commander and a nephew of Frederick the Great, two of the king’s brothers, Prince Henry and Prince William, a cousin and the Prince of Orange. Composed for the signatories by the court historiographer Johannes von Müller, the memorandum pulled few punches. In it, the king was accused of having abandoned the Holy Roman Empire and sacrificed his subjects and the credibility of his word of honour for the sake of the policy of ill-conceived self-interest pursued by the pro-French party among his ministers. Now he was further endangering the honour of his kingdom and his house by refusing to take a stand. The king saw in this document a calculated challenge to his authority and responded with rage and alarm. In a gesture evocative of an earlier era when brothers wrestled for thrones, the princes were ordered to leave the capital city and return to their regiments. As this episode reveals, the factional strife over foreign policy had begun to drift out of control. A determined ‘war party’ had emerged that included members of the king’s family, but was centred on the two ministers Karl August von Hardenberg and Karl vom Stein. Its objective was to put an end to the fudges and compromises of the neutrality policy. But its means implied the demand for a more broadly based decision-making process that would bind the king to a collegial deliberative mechanism of some kind.

Although the king resented deeply the impertinence, as he saw it, of the memorandum of 2 September, the charge of prevarication unsettled him deeply, sweeping aside his instinctive preference for caution and delay. And so it was that the Berlin decision-makers allowed themselves to be goaded into precipitate action, although the preparations for a coalition with Russia and Austria had scarcely begun to take concrete shape. On 26 September Frederick William III addressed a letter full of bitter recriminations to the French Emperor, insisting that the neutrality pact be honoured, demanding the return of various Prussian territories on the lower Rhine and closing with the words: ‘May heaven grant that we can reach an understanding on a basis that leaves you in possession of your full renown, but also leaves room for the honour of other peoples, [an understanding] that will put an end to this fever of fear and expectation, in which no one can count on the future.’ Napoleon’s reply, signed in the imperial headquarters at Gera on 12 October, reverberated with a breathtaking blend of arrogance, aggression, sarcasm and false solicitude.

Only on 7 October did I receive Your Majesty’s letter. I am extraordinarily sorry that You have been made to sign such a pamphlet. I write only to assure You that I will never attribute the insults contained within it to Yourself personally, because they are contrary to Your character and merely dishonour us both. I despise and pity at once the makers of such a work. Shortly thereafter I received a note from Your minister asking me to attend a rendezvous. Well, as a gentleman, I have kept to my appointment and am now standing in the heart of Saxony. Believe me, I have such powerful forces that all of Yours will not suffice to deny me victory for long! But why shed so much blood? For what purpose? I speak to Your Majesty just as I spoke to Emperor Alexander shortly before the Battle of Austerlitz. [… ] Sire, Your Majesty will be vanquished! You will throw away the peace of Your old age, the life of Your subjects, without being able to produce the slightest excuse in mitigation! Today You stand there with your reputation untarnished and can negotiate with me in a manner worthy of Your rank, but before a month is passed, Your situation will be a different one!

Thus spoke the ‘man of the century’, the ‘world soul on horseback’ to the King of Prussia in the autumn of 1806. The course was now set for the trial of arms at Jena and Auerstedt.

For Prussia, the timing could hardly have been worse. Since the army corps promised by Tsar Alexander had not yet materialized, the coalition with Russia remained largely theoretical. Prussia faced the might of the French armies alone, save for its Saxon ally. Ironically, the habit of delay that the war party so deplored in the king was now the one thing that could have saved Prussia. The Prussian and Saxon commanders had expected to give battle to Napoleon somewhere to the west of the Thuringian forest, but he advanced much faster than they had anticipated. On 10 October 1806, the Prussian vanguard made contact with French forces and was defeated at Saalfeld. The French then pushed past the flank of the Prussian armies and formed up with their backs to Berlin and the Oder, denying the Prussians access to their supply lines and routes of withdrawal. This is one reason why the subsequent breakdown of order on the battlefield proved so irreversible.

On 14 October 1806, the 26-year-old Lieutenant Johann von Borcke was posted with an army corps of 22,000 men under the command of General Ernst Wilhelm Friedrich von Rüchel to the west of the city of Jena. It was still dark when news arrived that Napoleon’s troops had engaged the main Prussian army on a plateau near the city. The noise of cannon fire could already be heard from the east. The men were cold and stiff from a night spent huddled on damp ground, but morale improved when the rising sun dispelled the fog and began to warm shoulders and limbs. ‘Hardship and hunger were forgotten,’ Borcke recalled. ‘Schiller’s Song of the Riders rang from a thousand throats.’ By ten o’clock, Borcke and his men were finally on the move towards Jena. As they marched eastward along the highway, they saw many walking wounded making their way back from the battlefield. ‘Everything bore the stamp of dissolution and wild flight.’ At about noon, however, an adjutant came galloping up to the column with a note from Prince Hohenlohe, commander of the main Prussian army fighting the French outside Jena: ‘Hurry, General Rüchel, to share with me the half-won victory; I am beating the French at all points.’ It was ordered that this message should be relayed down the column and a loud cheer went up from the ranks.

The approach to the battlefield took the corps through the little village of Kapellendorf; streets clogged with cannon, carriages, wounded men and dead horses slowed their progress. Emerging from the village, the corps came up on to a line of low hills, where the men had their first sight of the field of battle. To their horror, only ‘weak lines and remnants’ of Hohenlohe’s corps could still be seen resisting French attack. Moving forward to prepare for an attack, Borcke’s men found themselves in a hail of balls fired by French sharp-shooters who were so well positioned and so skilfully concealed that the shot seemed to fly in from nowhere. ‘To be shot at in this way,’ Borcke later recalled, ‘without seeing the enemy, made a dreadful impression upon our soldiers, for they were not used to that style of fighting, lost faith in their weapons and immediately sensed the enemy’s superiority.’

Flustered by the ferocity of the fire, commanders and troops alike became anxious to press ahead to a resolution. An attack was launched against French units drawn up near the village of Vierzehnheiligen. But as the Prussians advanced, the enemy artillery and rifle fire became steadily more intense. Against this, the corps had only a few regimental cannon, which soon broke down and had to be abandoned. The order ‘Left shoulder forward!’ was shouted down the line and the advancing Prussian columns veered to the right, twisting the angle of attack. In the process, the battalions on the left began to drift apart and the French, bringing up more and more cannon, cut larger and larger holes in the advancing columns. Borcke and his fellow officers galloped back and forth, trying to repair the broken lines. But there was little they could do to allay the confusion on the left wing, because the commander, Major von Pannwitz, was wounded and no longer on his horse, and the adjutant, Lieutenant von Jagow, had been killed. The Regimental Colonel von Walter was the next commander to fall, followed by General Rüchel himself and several staff officers.

Without awaiting orders, the men of Borcke’s corps began to fire at will in the direction of the French. Some, having expended their ammunition, ran with fixed bayonets at the enemy positions, only to be cut down by cartridge shot or ‘friendly fire’. Terror and chaos took hold, reinforced by the arrival of the French cavalry, who hoed into the surging mass of Prussians, slashing with their sabres at every head or arm that came within reach. Borcke found himself drawn along irresistibly with the masses fleeing the field westwards along the road to Weimar. ‘I had saved nothing,’ Borcke wrote, ‘but my worthless life. My mental anguish was extreme; physically I was in a state of complete exhaustion and I was being dragged along among thousands in the most horrific chaos…’

The battle of Jena was over. The Prussians had been defeated by a better-managed force of about the same size (there were 53,000 Prussians and 54,000 French deployed). Even worse was the news from Auerstedt a few kilometres to the north, where on the same day a Prussian army numbering some 50,000 men under the command of the Duke of Brunswick was routed by a French force half that size under Marshal Davout. Over the following fortnight, the French broke up a smaller Prussian force near Halle and occupied the cities of Halberstadt and Berlin. Further victories and capitulations followed. The Prussian army had not merely been defeated; it had been ruined. In the words of one officer who was at Jena: ‘The carefully assembled and apparently unshakeable military structure was suddenly shattered to its foundations.’ This was precisely the disaster that the Prussian neutrality pact of 1795 had been designed to avoid.

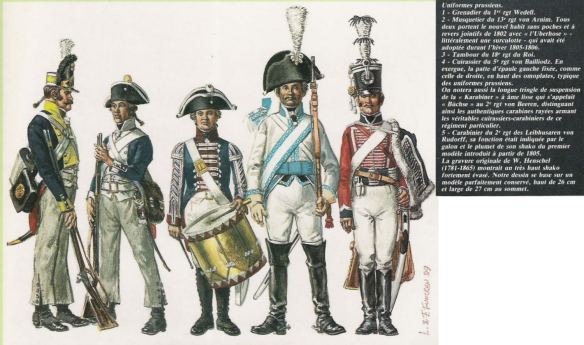

The relative prowess of the Prussian army had declined since the end of the Seven Years War. One reason for this was the emphasis placed upon increasingly elaborate forms of parade drill. These were not a cosmetic indulgence – they were underwritten by a genuine military rationale, namely the integration of each soldier into a fighting machine answering to one will and capable of maintaining cohesion under conditions of extreme stress. While this approach certainly had strengths (among other things, it heightened the deterrent effect upon foreign visitors of the annual parade manoeuvres in Berlin), it did not show up particularly well against the flexible and fast-moving forces deployed by the French under Napoleon’s command. A further problem was the Prussian army’s dependence upon large numbers of foreign troops – by 1786, when Frederick died, 110,000 of the 195,000 men in Prussian service were foreigners. There were very good reasons for retaining foreign troops; their deaths in service were easier to bear and they reduced the disruption caused by military service to the domestic economy. However, their presence in such large numbers also brought problems. They tended to be less disciplined, less motivated and more inclined to desert.

To be sure, the decades between the War of the Bavarian Succession (1778–9) and the campaign of 1806 also saw important improvements. Mobile light units and contingents of riflemen (Jäger) were expanded and the field requisition system was simplified and overhauled. None of this sufficed to make good the gap that swiftly opened up between the Prussian army and the armed forces of revolutionary and Napoleonic France. In part, this was simply a question of numbers – as soon as the French Republic began scouring the French working classes for domestic recruits under the auspices of the levée en masse, there was no way the Prussians would be able to keep pace. The key to Prussian policy ought therefore to have been to avoid at all costs having to fight France without the aid of allies.

From the beginning of the Revolutionary Wars, moreover, the French had integrated infantry, cavalry and artillery in permanent divisions supported by independent logistic services and capable of sustaining autonomous mixed operations. Under Napoleon, these units were grouped together into army corps with unparalleled flexibility and striking power. By contrast, the Prussian army had scarcely begun to explore the possibilities of combined-arms divisions by the time they faced the French at Jena and Auerstedt. The Prussians were also a long way behind the French in the use of sharp-shooters. Although, as we have seen, efforts had been made to expand this element of the armed forces, overall numbers remained low, the weaponry was not of the highest standard and insufficient thought was given to how the deployment of riflemen could be integrated with the deployment of large troop masses. Lieutenant Johann Borcke and his fellow infantrymen paid dearly for this gap in tactical flexibility and striking power as they stumbled on to the killing field at Jena.

Frederick William III had initially intended to open peace negotiations with Napoleon after Jena and Auerstedt, but his approaches were rebuffed. Berlin was occupied on 24 October and three days later Bonaparte entered the capital. During a brief sojourn in nearby Potsdam, he made a famous visit to the tomb of Frederick the Great, where he is said to have stood deep in thought before the coffin. According to one account, he turned to the generals who were with him and remarked: ‘Gentlemen, if this man were still alive, I would not be here.’ This was partly imperial kitsch and partly a genuine tribute to the extraordinary reputation Frederick enjoyed among the French, especially the patriot networks that had helped to revitalize French foreign policy and had always seen the Austrian alliance of 1756 as the greatest error of the French ancien régime . Napoleon had long been an admirer of the Prussian king: he had pored through Frederick’s campaign narratives and had a statuette of him placed in his personal cabinet. The young Alfred de Vigny even claimed with a certain amusement to have observed Napoleon affecting Frederician poses, ostentatiously taking snuff, making flourishes with his hat ‘and other similar gestures’ – eloquent testimony to the continuing resonance of the cult. By the time the French Emperor stood in Berlin paying his respects to the dead Frederick, his living successor had fled to the easternmost corner of the kingdom, evoking parallels with the dark days of the 1630s and 1640s. The state treasure, too, was saved in the nick of time and transported away to the east.

Napoleon was now ready to offer peace terms. He demanded that Prussia renounce all its territories to the west of the river Elbe. After some agonized wavering, Frederick William III signed an agreement to this effect at the Charlottenburg palace on 30 October, whereupon Napoleon changed his mind and insisted that he would agree to an armistice only if Prussia consented to serve as the operational base for a French attack upon Russia. Although the majority of his ministers supported this option, Frederick William sided with the minority who preferred to continue the war at Russia’s side. Everything now depended upon whether the Russians would be able to put sufficient forces in the field to halt the momentum of the French advance.

During the months from late October 1806 to January 1807, French forces had steadily advanced through the Prussian lands, forcing or accepting the capitulation of key fortresses. On 7 and 8 February 1807, however, they were repulsed at Preussisch-Eylau by a Russian force with a small Prussian contingent. Sobered by this experience, Napoleon returned to the armistice offer of October 1806, under which Prussia would merely give up its West-Elbian territories. Now it was Frederick William’s turn to refuse, in the hope that renewed Russian attacks would push the balance further to Prussia’s advantage. These were not forthcoming. The Russians failed to capitalize on the advantage gained at Preussisch-Eylau and the French continued throughout January and February to subdue the Prussian fortresses in Silesia. In the meanwhile, Hardenberg, who was still operating the pro-Russian policy with which he had triumphed in 1806, negotiated an alliance with St Petersburg that was signed on 26 April 1807. The new alliance was short lived; after a French victory over the Russians at Friedland on 14 June 1807, Tsar Alexander asked Napoleon for an armistice.

On 25 June 1807, Emperor Napoleon and Tsar Alexander met to begin peace negotiations. The setting was unusual. A splendid raft was built on Napoleon’s orders and tethered in the middle of the river Niemen at Piktupönen, near the East Prussian town of Tilsit. Since the Niemen was the official demarcation line of the ceasefire and the Russian and French armies were drawn up on opposite banks of the river, the raft was an ingenious solution to the need for neutral ground where the two emperors could meet on an equal footing. Frederick William of Prussia was not invited. Instead he stood miserably on the bank for several hours, surrounded by the Tsar’s officers and wrapped in a Russian overcoat. This was just one of the many ways in which Napoleon advertised to the world the inferior status of the defeated King of Prussia. The rafts on the Memel were adorned with garlands and wreaths bearing the letters ‘A’ and ‘N’ – the letters FW were nowhere to be seen, although the entire ceremony was taking place on Prussian territory. Whereas French and Russian flags could be seen everywhere fluttering in the mild breeze, the Prussian flag was conspicuous by its absence. Even when, on the following day, Napoleon invited Frederick William into his presence on the raft, the resulting conversation had the flavour of an audience rather than a meeting between two monarchs. Frederick William was made to wait in an antechamber while the Emperor saw to some overdue paperwork. Napoleon refused to inform the king of his plans for Prussia and hectored him about the many military and administrative errors he had made during the war.