The Russian army was a peasant army – serfs and state peasants were the main groups subject to the military draft – and that was its main problem. It was by far the biggest army in the world, with over a million infantry, a quarter of a million irregulars (mainly Cossack cavalry) and three-quarters of a million reservists in special military settlements. But even this was not enough to defend the enormous borders of Russia, where there were so many vulnerable points, such as the Baltic coast, or Poland, or the Caucasus, and the army could not recruit more without running down the serf economy and sparking peasant uprisings. The weakness of the population base in European Russia – a territory the size of the rest of Europe but with less than a fifth of its population – was compounded by the concentration of the serf population in the central agricultural zone of Russia, a long way from the Empire’s borders where the army would be needed at short notice in the event of war. Without railways it took months for serfs to be recruited and sent by foot or cart to their regiments. Even before the Crimean War, the Russian army was already overstretched. Virtually all the serfs eligible for conscription had been mobilized, and the quality of the recruits had declined significantly, as landowners and villages, desperate to hold on to their last able farmers, sent inferior men to the army. A report of 1848 showed that during recent levies one-third of the conscripts had been rejected because they had failed to meet the necessary height requirement (a mere 160 centimetres); and another half had been rejected because of chronic illness or other physical deficiencies. The only way to solve the army’s shortages of manpower would have been to widen its social base of conscription and move towards a European system of universal military service, but this would have spelled the end of serfdom, the foundation of the social system, to which the aristocracy was firmly committed.

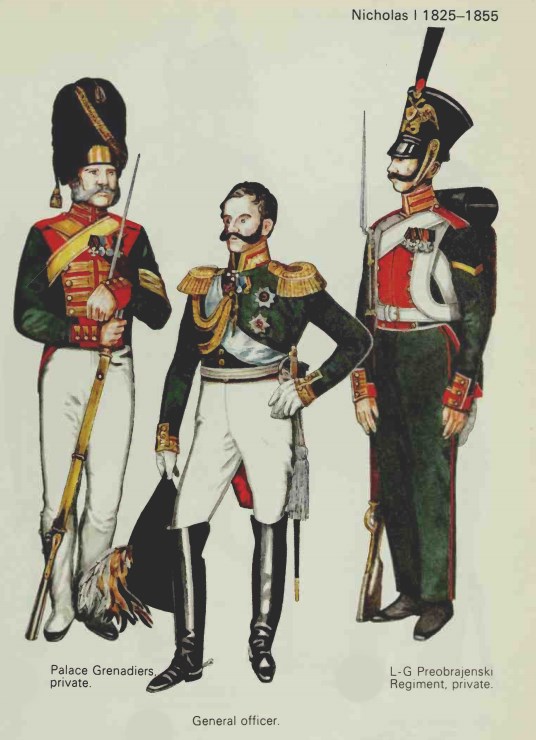

Despite two decades of reform, the Russian military remained far behind the armies of the other European states. The officer corps was poorly educated and almost all the troops illiterate: official figures of the 1850s showed that in a group of six divisions, numbering approximately 120,000 men, only 264 (0.2 per cent) were able to read or write. The ethos of the army was dominated by the eighteenth-century parade-ground culture of the tsarist court, in which promotion, to quote Karl Marx, was limited to ‘martinets, whose principal merit consists of stolid obedience and ready servility added to accuracy of eyesight in detecting a fault in the buttons and buttonholes of the uniform’. There was more emphasis on the drilling and appearance of the troops than on their battleworthiness. Even during fighting there were elaborate rules for the posture, length of stride, line and movement of the troops, all set out in army manuals, which were quite irrelevant to the actual conditions of the battlefield:

When a battle formation is advancing or retiring it is necessary to observe a general alignment of the battalions in each line and to maintain correctly the intervals between battalions. In this case it is not enough for each battalion separately to keep alignment, it is necessary that the pace be alike in all battalions, so that the guidon sergeants marching before the battalions shall keep alignment among themselves and march parallel to one another along lines perpendicular to the common formation.

The domination of this parade culture was connected to the backwardness of the army’s weaponry. The importance attached to keeping troops in tight columns was partly to maintain their discipline and prevent chaos when there were large formations on the move, as in other armies of the time. But it was also necessitated by the inefficiency of the Russian musket and the consequent reliance on the bayonet (justified by patriotic myths about the ‘bravery of the Russian soldier’, who was at his best with the bayonet). Such was the neglect of small-arms fire in the infantry that ‘very few men even knew how to use their muskets’, according to one officer. ‘With us, success in battle was entirely staked on the art of marching and the correct stretching of the toe.’

These outdated means of fighting had brought Russia victory in all the major wars of the early nineteenth century – against the Persians and the Turks, and of course in Russia’s most important war, against Napoleon (a triumph that convinced the Russians that their army was invincible). So there had been little pressure to update them for the needs of warfare in the new age of steam and the telegraph. Russia’s economic backwardness and financial weakness compared to the new industrial powers of the West also placed a severe brake on the modernization of its vast and expensive peacetime army. It was only during the Crimean War – when the musket was shown to be useless against the Minié rifle of the British and the French – that the Russians ordered rifles for their own army.

Of the 80,000 Russian troops who crossed the River Pruth, the border between Russia and Moldavia, less than half would survive for a year. The tsarist army lost men at a far higher rate than any of the other European armies. Soldiers were sacrificed in huge numbers for relatively minor gains by aristocratic senior officers, who cared little for the welfare of their peasant conscripts but a great deal for their own promotion if they could report a victory to their superiors. The vast majority of Russian soldiers were not killed in battle but died from wounds and diseases that might not have been fatal had there been a proper medical service. Every Russian offensive told the same sad tale: in 1828–9, half the army died from cholera and illnesses in the Danubian principalities; during the Polish campaign of 1830–31, 7,000 Russian soldiers were killed in combat but 85,000 were carried off by wounds and sickness; during the Hungarian campaign of 1849, only 708 men died in the fighting but 57,000 Russian soldiers were admitted to Austrian hospitals. Even in peacetime the average rate of sickness in the Russian army was 65 per cent.

The appalling treatment of the serf soldier lay behind this high rate of illness. Floggings were a daily aspect of the disciplinary system; beatings so common that entire regiments could be made up of men who carried wounds inflicted by their own officers. The supply system was riddled with corruption because officers were very badly paid – the whole army was chronically underfunded by the cash strapped tsarist government – and by the time they had taken their profit from the sums they were allowed to buy provisions with, there was little money left for the rations of the troops. Without an effective system of supply, soldiers were expected to fend largely for themselves. Each regiment was responsible for the manufacturing of its uniforms and boots with materials provided by the state. Regiments not only had their own tailors and cobblers, but their own barbers, bakers, blacksmiths, carpenters and metal workers, joiners, painters, singers and bandsmen, all of them bringing their own village trades into the army. Without these peasant skills, a Russian army, let alone an army on the offensive, would not have been feasible. The Russian soldier on the march drew on all his peasant know-how and resourcefulness. He carried bandages in his knapsack so that he could treat himself for wounds. He was very good at improvising ways to sleep in the open – using leaves and branches, haystacks, crops, and even digging himself into a hole in the ground – a crucial skill that helped the army to go on long marches without the need to carry tents.