The Battle of Biscay, 28 December 1943.

In the wake of the disaster at Narvik on 13 April 1940, the four existing Z-Flottillen were disbanded and reformed under a caretaker FdZ, Fregattenkapitän Alfred Schemmel, between 18 April and 14 May 1940. Kapitän zur See Erich Bey was appointed on the latter date, and he held the post until his death aboard the battleship Scharnhorst on 26 December 1943.

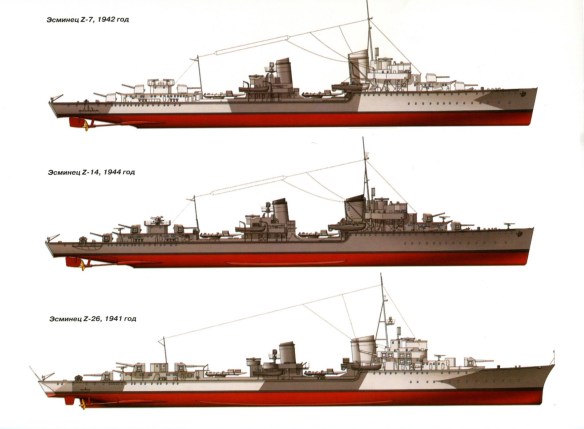

The two new flotillas were numbered 5 and 6. 5. Z-Flottille consisted of the former 1. Z-Flottille based at Swinemünde—Z 4 Richard Beitzen, Z 14 Friedrich Ihn, Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck and Z 16 Friedrich Eckholdt. 6. Z-Flottille comprised the remaining survivors, Z 5 Paul Jacobi, Z 6 Theodor Riedel, Z 7 Hermann Schoemann, Z 8 Bruno Heinemann, Z 10 Hans Lody and Z 20 Karl Galster. These flotillas had little real significance because the small number of ships and their lack of operational readiness led to units being sent wherever the necessity for them arose. During 1940 three new destroyers, Z 23, Z 24 and Z 25, entered service, but they were not combat-ready until March 1941.

No destroyer operations were carried out in the Baltic east of the Kattegat in 1940, and there were no further German destroyer losses during 1940.

The immediate priority following the occupation of Norway was to close down the Skagerrak, and on 28 April Z 4 Richard Beitzen and Z 8 Bruno Heinemann took part in the first day’s operation to lay the Sperre 17 mine barrage in company with the minelayers Roland, Kaiser, Preussen and Cobra. The torpedo boats Leopard, Möwe and Kondor were also present, though Leopard was sunk in a collision with Preussen. After an improvement in the weather, the work was completed on 17 and 19 May, Z 4 being accompanied by Z 7 Hermann Schoemann on these two latter occasions.

At the beginning of June an operation codenamed ‘Juno’ was begun, the objective of which was to penetrate to the end of Andfjord and attack the town of Harstad, which British forces had invested as a naval base with a view eventually to re-taking Narvik. At 0800 on 4 June a German formation led by the battleship Gneisenau, flagship of Admiral Marschall, set out northwards from Kiel. In line astern followed the battleship Scharnhorst, the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and the destroyers Hans Lody, Hermann Schoemann, Erich Steinbrinck and Karl Galster. The attack on Harstad was planned for the early hours of 9 June, but once it had been confirmed that the British and French occupation force had abandoned the town, and a full evacuation from Norway was in progress, Gruppe West ordered Marschall to attack a reported convoy instead. A scouting line with 10nm between each ship was formed, and at 0605, in position 67°20’N 04°00’E the sweep encountered a westbound tanker, Oil Pioneer (5,666grt), escorted by the 530-ton ‘Tree’ class corvette Juniper—’an unwelcome stop in our search for the valuable convoy with its cruiser and destroyer escort’, Marschall recorded. While Gneisenau dealt with the tanker, leaving Hermann Schoemann to rescue the eleven survivors, Admiral Hipper finished off the corvette. Juniper’s depth charges exploded as she sank, leaving only one survivor to be picked up by Hans Lody.

The search line re-formed, and shortly after 1000 Lody reported smoke from several ships to the north which proved to be the hospital ship Atlantis, which was allowed to proceed unmolested, and the empty troop transporter Orama (19,840grt). The latter was suspected to be an AMC, and when, at 1104, movement on deck was interpreted as an attempt to man her guns, Hipper turned broadside-on and opened fire with tailfused salvos from all her main turrets at a range of 13,000yds. Lody began shooting at the same time, and, just as she was being ordered via ultra-short wave radio to cease firing, Hipper’s, foretop rangefinder operator reported that the Orama had struck her flag and was being abandoned by her crew. Lody had the Orama on a bearing from which it was not possible to see the transport’s lifeboats being lowered—and her ultrashort wave radio was not functioning. She therefore received neither the order from Hipper to cease firing nor one from the fleet commander not to fire torpedoes. Hans Lody unfortunately continued to shell the stricken ship and, to hasten her demise, loosed off two torpedoes. Both of these were rogues, but although one was a surface-runner which hit a loaded lifeboat at 40 knots and failed to explode, the other deviated and detinated prematurely close to Hipper. At 1220 the Orama sank by the stern, leaving fourteen survivors to be picked up by the heavy cruiser and 98 by the destroyer. An hour later the cruiser and destroyers were sent into Trondheim to refuel.

On 10 June the cruiser sortied in company with the battleship Gneisenau and the same four destroyers— Z 7, Z 10, Z 15 and Z 20—to attack British shipping, but as a result of adverse Luftwaffe reconnaissance reports were back at their moorings the next day. Bomber aircraft attacked the German units on several occasions.

Between 14 and 17 June, in an operation codenamed ‘Nora’, the cruiser Nürnberg, Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck and a minesweeping flotilla escorted the troopship Levante with 3. Gebirgsjager Division from Trondheim to Elvegardsmoen in Narvikfjord, returning with the paratroop force relieved there.

On 20 June the battleship Scharnhorst, which had been torpedoed during the action in which she and her sister-ship Gneisenau sank the aircraft carrier Glorious and three destroyers, left Trondheim for Kiel flanked by Z 7 Hermann Schoemann, Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck, Z 10 Hans Lody and several torpedo boats; that same evening Admiral Hipper and Gneisenau sailed from Trondheim escorted by Z 20 Karl Galster and a seaplane on an operation to ‘roll up’ the British Northern Patrol, this having the secondary purpose of distracting attention from the departure of Scharnhorst. Shortly before midnight, at the entrance to Trondheimfjord, the submarine Clyde torpedoed Gneisenau forward of ‘A’ turret and the German force had to turn back.

On 25 July Hipper left Trondheim in company with the homebound damaged Gneisenau and her escort, consisting of the cruiser Nürnberg, Z 5 Paul Jacobi, Z 14 Friedrich Ihn and Z 20 Karl Galster. As arranged, Hipper was soon detached and steered north alone for anti-contraband reconnaissance in polar waters, and the force for Kiel was reinforced the next day by the torpedo boats Seeadler, Iltis, Jaguar, Luchs and T 5. Luchs was sunk when she intercepted a torpedo intended for Gneisenau from the British submarine Swordfish, but the remainder of the convoy reached Kiel on 28 June.

Between 31 August and 2 September Z 5 Paul Jacobi, Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck, Z 20 Karl Galster and four torpedo boats assisted the minelayers Tannenberg, Roland and Cobra to lay the Sperre 3 barrage in the south-western North Sea.

From 13 September 1940 Admiral Hipper was on standby at Kiel for Operation ‘Seelöwe’ (Sealion), the planned invasion of Britain, for which her task was to make a diversionary break-out to the north of either Scotland or Ireland to lure the Home Fleet out of the English Channel. All operational destroyers were sent to the French Channel ports of Brest and Cherbourg during September and October for ‘Seelöwe’ : Z 6 Theodor Riedel, Z 10 Hans Lody, Z 14 Friedrich Ihn, Z 16 Friedrich Eckholdt and Z 20 Karl Galster sailed from Germany on 9 September, followed on the 22nd by Z 5 Paul Jacobi and Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck. Z 6 Theodor Riedel was of little use on account of persistent problems with her port engine. Z 4 Richard Beitzen arrived on 21 October.

The principal operations carried out against the British south coast occurred on the night of 28 September, when Falmouth Bay was mined by Paul Jacobi, Hans Lody, Friedrich Ihn and Friedrich Eckholdt; on 17 October, when Hans Lody, Friedrich Ihn, Erich Steinbrinck, Karl Galster and 5. Torpedobootflottille skirmished briefly with a mixed force of Royal Navy cruisers and destroyers in the Western Approaches (Lody was struck twice by shells); and in the early morning of 19 November when, off Plymouth, Richard Beitzen, Hans Lody and Karl Galster engaged the destroyers Jupiter, Javelin, Jackal, Jersey and Kashmir, Galster suffering light splinter damage and Javelin being torpedoed forward and aft.

With the abandonment of ‘Seelöwe’ in October, German destroyers had begun to trickle away from Brest and Cherbourg to Germany to refit and repair, and by early December Z 4 Richard Beitzen, at Brest, was the only German destroyer operational anywhere.

Six new destroyers (Z 23–28) became operational during 1941, and, as no destroyers were lost, the total available for duty at the end of the year rose to sixteen. Z 4 Richard Beitzen remained the only destroyer active off the French coast until March. She escorted Admiral Hipper out of Brest at the commencement the cruiser’s second raiding operation and met her on her return to the French port on 14 February.

Z 4 left for Germany on 16 March and was replaced in early April by Z 8 Bruno Heinemann, Z 14 Friedrich Ihn and Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck, which were based at La Pallice. From 22 to 24 April these destroyers escorted Thor across Biscay to Cherbourg on the completion of the raider’s successful Atlantic cruise. In May Z 8 and Z 15 repeated the exercise for the naval oiler Nordmark after her six-month sojourn in mid-Atlantic replenishing the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer. In the morning of 1 June all three destroyers met the cruiser Prinz Eugen as she put in at Brest astern of Sperrbrecher 13 at 1525 to conclude the disastrous ‘Rheinübung’ operation (in which the battleship Bismarck was sunk).

In mid-June the new destroyers Z 23 and Z 24 arrived at Brest and together with Z 8 and Z 15 ran escort for the battleship Scharnhorst on her occasional movements down the Breton coast. On 24 July, while engaged in gunnery practice off La Pallice, Scharnhorst was bombed and had to return to Brest for repair. From 21 to 23 August Z 23, Z 24, Erich Steinbrinck and Bruno Heinemann escorted the raider Orion across the Bay of Biscay and into the Gironde estuary after her epic seventeen-month cruise (all incoming prizes and steamers headed for St-Nazaire or the Gironde estuary using the so-called ‘Prize Channel’. By the end of October all the destroyers based in France had returned to Germany.

Meanwhile, further north, between 26 and 28 March Z 23 escorted Admiral Hipper into Kiel after the latter’s break-out from Brest, and the same destroyer met Admiral Scheer returning from the Indian Ocean on 30 March, the voyage finishing at Kiel on 1 April. At 1125 on 19 May, off Cape Arcona, Rügen Island, the battleship Bismarck and heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen moved off astern of a protective screen formed by Z 15 Erich Steinbrinck, Z 23 and two Sperrbrecher for the southern entrance to the Great Belt, where Z 10 Hans Lody, several minesweepers and eight aircraft joined for the crossing of the Skagerrak. At 0900 the next morning Prinz Eugen and the destroyers put into Korsfjord and refuelled in Kalvenes Bay. At 2000 the battle group assembled behind the destroyer screen, reaching the open sea by way of Hjeltefjord at 2200 on 21 May. The destroyers were released into Trondheim at 0510 the following morning.

On 11 June 1941 the light cruiser Leipzig, the destroyers Z 16 Friedrich Eckholdt and Z 20 Karl Galster, three torpedo boats, two U-boats and a large air escort set out from Kiel to accompany the heavy cruiser Lützow (formerly the pocket battleship Deutschland) on the first stage of Operation ‘Sommerreise’, a raiding cruise to the Indian Ocean. The naval escort terminated at Oslofjord, and Lützow continued alone. She got as far as Egersund before being crippled by an RAF torpedobomber. Z 10 Hans Lody and Z16 Friedrich Eckholdt escorted her back to the yards at Kiel on 14 June.

With the opening of the campaign against the Soviet Union—‘Barbarossa’—a two-part Baltic Fleet was formed. On 23 September 1941 the northern group, comprising the battleship Tirpitz, the cruisers Nürnberg and Köln and the new destroyers Z 25, Z 26 and Z 27, left Swinemünde for the Gulf of Finland to intercept Russian warships seeking internment in Sweden. On 27 September the force appeared off the Aba-Aaland skerries, but, as it turned out, the Red Fleet had no intention of leaving Kronstadt.

Shortly after the outbreak of war with the Soviet Union, 6. Z-Flottille (Kapitän zur See Alfred Schulze-Hinrichs), consisting of Z 4 Richard Beitzen, Z 7 Hermann Schoemann, Z 10 Hans Lody, Z 16 Friedrich Eckholdt and Z 20 Karl Galster, set out for northern Norway, arriving on 10 July at Kirkenes, a port in the Barents Sea close to the Kola peninsula and Murmansk. On 12 July the force split into two groups and on the first foray attacked a small Russian convoy of tugs, sinking the Soviet patrol ship Passat and a trawler. In a three-day sortie near the port of Iokanga on the Kola peninsula near the mouth of the White Sea, Z 4, Z 7, Z 16 and Z 20 sank the Soviet survey ship Meridian, but a similar raid which set out on 29 July was broken off after the Luftwaffe reported an approaching British force of two carriers, two cruisers and four destroyers which subsequently attacked Kirkenes.

On 9 and 10 August 1941 Beitzen, Lody and Eckholdt operated in the Kildin-Kola Inlet area, where, in a short engagement, the Soviet patrol vessel SKR-12 was sunk. Beitzen was straddled by enemy fire but not hit. When Z 4 and Z 7 returned to Germany for repairs in August, the remaining three destroyers were limited to escort duties following the British attack on the Bremse convoy of 6 September.

By November the Seekriegsleitung had recognised the frequency of the British Murmansk convoys and decided to adopt a far more aggressive policy in the Arctic. For this purpose 8. Z-Flottille (Kapitän zur See Gottfried Pönitz), composed of five new destroyers together with four E-boats and six U-boats, was sent to Kirkenes to relieve 6. Z-Flottille, the heavy ships following shortly afterwards.

From 16 to 18 December Z 23, Z 24, Z 25, and Z 27 — Z 26 turned back with engine trouble—sailed to lay a minefield north of Cape Gordodetzky on the Kola peninsula at the entrance to the White Sea but were disturbed by the Murmansk-based Halcyon class minesweeping sloops Speedy and Hazard, which had set out to escort convoy PQ.6. Speedy was hit and seriously damaged by four 15cm shells, but the German destroyers broke off the action when two Russian destroyers and the heavy cruiser Kent steamed out of the Kola Inlet to engage. On Boxing Day Z 23, Z 24, Z 25 and Z 27 operated off the Lofoten Islands following the British commando raid there at Christmas when an important radio mast had been destroyed and the small German naval base at Vaagso attacked.

During the course of 1942 Z 7 Hermann Schoemann, Z 8 Bruno Heinemann and Z 16 Friedrich Eckholdt, plus Z 26, were lost, and Z 29, Z 30 and Z 31 became operational, as did ZG 3 Hermes in the Mediterranean. By the end of the year sixteen destroyers were available—the same number as on 31 December 1941. Throughout 1942 all destroyer operations were concentrated in Norwegian waters: even Operation ‘Cerberus’ — the ‘Channel Dash’ — in February having as its primary object the removal of three heavy units from Brest to Norway.

The year opened with the laying of a 100-mine EMC field by the Kirkenes-based destroyers Z 23, Z 24 and Z 25 on 13 January in the western channel of the entrance to the White Sea near Cape Kocovsky. Meanwhile the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen had been at Brest for between six and nine months, and it was decided to extricate them by sailing them through the English Channel in broad daylight—the so-called ‘Channel Dash’. Final discussions on the planned break-out from Brest were held in Paris on 1 January, those present including Admírale Saalwächter, Schniewind and Ciliax and the commanders of the three heavy units. Hitler gave his consent to the operation on 12 January. Towards the end of the month seven destroyers were despatched to Brest, but on 25 January, off Calais, Z 8 Bruno Heinemann, sailing in a group with Z 4, Z 5 and Z 7, struck two mines and sank—the first German destroyer lost since Narvik. Later Z 14, Z 25 and Z 29 arrived at Brest without incident. It was suspected that the principal target during the ‘Channel Dash’ would be Prinz Eugen, because of her part in sinking the battlcruiser Hood the previous May, and she was fitted with an extra five quadruple AA guns and allocated Z 14 Friedrich Ihn, which carried an unusual amount of sophisticated technology, as escort. Notice for steam was given for 2030 on 11 February. In command of the squadron was Vizeadmiral Ciliax, on board the flagship Scharnhorst.

Sailing was delayed by an air raid warning, and when the ships weighed anchor at 2245 their departure went unnoticed, the British submarine keeping watch off the port being engaged in recharging her batteries offshore. Escorting the three heavy ships—steaming in the order Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Prinz Eugen—were the destroyers Z 4 Richard Beitzen, Z 5 Paul Jacobi, Z 7 Hermann Schoemann, Z 14 Friedrich Ihn, Z 25 and Z 29; the torpedo boats T 11, T 2, T 5, T 12 and T 4 of the 2nd Flotilla, T 13, T 15, T 16 and T 17 of the 3rd Flotilla and Seeadler, Falke, Kondor, litis and Jaguar of the 5th Flotilla; and the 2nd, 4th and 6th E-boat Flotillas. Luftwaffe air cover comprised 176 Bf 110s and fighters.

The British were not alerted to the passage of the German armada until it was beyond Calais. The wind was south-west force 6 and the sea state 5. The first MTB attacks began at 1320, after the ships were beyond the range of the Dover batteries. Next came a suicidal low-level attack by six Swordfish torpedo bombers, all of which were shot down, one by the Luftwaffe, two by Friedrich Ihn and three by Prinz Eugen firing in barrage. In the North Sea the German units had the advantages of favourable weather and a heavy air umbrella.

In the entire action, 42 of the 600 British aircraft engaged were destroyed. When Scharnhorst was mined off the Scheldt, Ciliax transferred to Z 29, but, finding she had engine and other battle damage, he raised his flag aboard Z 7 Hermann Schoemann for the run to port.

At 0245 on 20 February Prinz Eugen (flagship of Vizeadmiral Ciliax) and Admiral Scheer left Brunsbüttel for Norway accompanied by Beitzen, Jacobi, Schoemann and Z 25. When reported by air reconnaissance before midday, the group reversed course for a while to throw the enemy off the scent. An unsuccessful air attack resulted in one aircraft being shot down. The ships put into Grimstadfjord on 22 February and left for Trondheim the same evening, but the escort was reduced by 50 per cent when Beitzen and Jacobi were forced into Bergen on account of damage cause by the heavy weather.

At 0702 the next morning, Trident—one of four British submarines positioned off the coast—hit Prinz Eugen’s stern with a torpedo which knocked off her rudder though left her propellers undamaged. The after section was almost severed, and the cruiser was unmanoeuvrable. Defensive measures prevented further attacks, and the unfortunate vessel limped into Lofjord during the night of 24 February. The scale of the damage was such that repairs in a German shipyard was dictated, and emergency work was begun at once alongside the workshop vessel Huascaran.

On 5 March German aircraft south of Jan Mayen reported a fifteen-ship convoy sailing on an eastward heading. This proved to be PQ. 12, and at the same time convoy QP.8 was sailing westwards for Iceland. The battleship Tirpitz, in company with Z 14 Friedrich Ihn, Z 7 Hermann Schoemann and Z 25, sailed from Trondheim to intercept the merchantmen but missed the convoys in storm and fog, their only victim being the straggling Soviet freighter Izora, sunk on 7th March by Ihn.

On 19 March Admiral Hipper sailed north from Brunsbüttel in company with the destroyers Z 24, Z 26 and Z 30 and the torpedo boats T 15, T 16 and T 17 and on the 21st joined the heavy cruisers Admiral Scheer and Prinz Eugen in Lofjord near Trondheim. In the evening of 28 March the Kirkenes destroyers Z 24, Z 25 and Z 26 took on the role of light cruisers to attack convoy PQ.13. After having sunk the straggler Bateau—which was stopping to rescue her crew and that of the Empire Ranger found adrift in lifeboats—the trio were surprised in poor visibility in the morning of 29 March by the cruiser Trinidad (8,000 tons, 33 knots, 12×6in guns, 2 torpedo tubes) and the destroyer Fury (1,350 tons, 36 knots, 4×14.7in guns, 8 torpedo tubes). Z 26 was seriously damaged and set on fire after hits from Trinidad but found refuge in a snow squall. When contact was renewed, the British cruiser attempted to torpedo Z 26. Her tubes were iced over, however, and the only torpedo to come free was a rogue which circled back and hit the ship which had fired it. Z 24 and Z 25 missed the cruiser with torpedoes. Short exchanges occurred in the poor visibility between snow showers, culminating in a second British destroyer, Eclipse (1,375 tons, 4×4.7in, 8 torpedo tubes) shooting Z 26 to a standstill. Z 24 and Z 25 rained shells down on to Eclipse but eventually allowed her to escape, preferring to save Z 26’s crewmen before the destroyer sank in waters which the human body could not survive for more than a minute or so. Even so, the death toll aboard Z 26 was grievous: 283 men failed to return home.

On 9 April 1942 Z 7 Hermann Schoemann sailed for Kirkenes as a replacement for the sunken Z 26, and on 1 May she sortied with Z 24 and Z 25 to attack convoy QP. 11, which had already been intercepted by U-boats. The convoy was relatively well protected. Close in was the light cruiser Edinburgh (10,000 tons, 32 knots, 12×6in guns) and the destroyers Forester and Foresight (1,350 tons, 36 knots, 4×4.7in, 8 torpedo tubes), the remaining escort being composed of the destroyers Bulldog and Beagle (1,360 tons, 35 knots, 4×4.7in, 8 torpedo tubes), Amazon (1,352 tons, 37 knots, 4×4.7in, six torpedo tubes) and Beverley (1,190 tons, 25 knots, 3×4in, 3 torpedo tubes), plus four corvettes and a trawler. Well to the rear were some Soviet vessels coming up from Murmansk. Edinburgh had been torpedoed by U 456 on 30 April.

In thick snowfall and drift ice, the three German destroyers clashed first with the four outer destroyers, damaging Amazon. Shortly afterwards they came across the motionless Edinburgh. Her guns were still intact, and she soon had Hermann Schoemann wallowing, one of the first hits knocking out the destroyer’s main steam feed, causing her current and both turbines to fail. Attempts by Z 24 and Z 25 to finish off Edinburgh with torpedoes were frustrated by iced-up tubes, only one torpedo getting clear. After laying a smoke screen to protect Z 7, they then took on Forester and Foresight, inflicting serious damage on both, but Z 25 had four dead in her radio room as a result of a direct hit. Edinburgh later sank. After picking up what survivors from Schoemann she could find, Z 24 scuttled Z 7 with explosives. U 88 found a number of the destroyer’s survivors in boats and on rafts, her final tally of dead being eight.