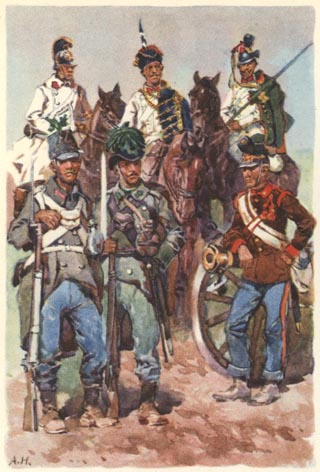

Austrian Troops

“The last stand.” Artillery units sacrifice themselves to cover the retreat of the Austrian army on July 3, 1866 at Königgätz/Sadowa, the battle that established Prussian/German hegemony in Central Europe.

The Austro-Hungarian artillery was a lot better there than the Prussian. Without the bravery of the Austrian artillery the battle would have ended as a bigger disaster than it already was. The Austrian guns were more efficient and shot “at the point”. Archduke Wilhelm as Inspector General of the Artillery did best work in the days before the battle. Most of the 700 guns were dug in and had pre-measured shooting-plans. The breechloading rifles were a cause for the high rate of dead and wounded but they were not the reason for losing the battle by the Austrians.

In contemporary military opinion, the Austrians were greatly superior in all arms to their adversary. Their rifle, though a muzzle-loader, was in every other respect superior to the Prussian needle-gun, and their M.L. rifled guns with shrapnel shell were considered more than sufficient to make good the slight advantage then conceded to the breech-loader. The cavalry was far better trained in individual and real horsemanship and manoeuvre, and was expected to sweep the field in the splendid cavalry terrain of Moravia. All three arms trained their men for seven years, and almost all officers and non-commissioned officers had considerable war experience. But the Prussians having studied their allies in the war of 1864 knew the weakness of the Austrian staff and the untrustworthiness of the contingents of some of the Austrian nationalities, and felt fairly confident that against equal numbers they could hold their own.

The Austrian Army was maintained by a conscription system which allowed the buying of substitutes. The Army as a whole was not as homogeneous as the Prussian, taking in units from across the empire and it was not as well organized, having no Divisional level of command. The peacetime organization consisted of seven Army Corps, each of 4 brigades, plus cavalry and artillery. For the Austro Prussian war this was expanded to 10 Corps, resulting in considerable disorganization.

Infantry were armed with a muzzle¬-loading rifle. This out ranged the Prussian needle gun but was much slower to load. Moreover, since a soldier was only allowed 20 practice rounds per year, the standard of accuracy was appalling.

Artillery was strong. All guns were rifled and had an effective range of about 2000 paces, again out ranging the Prussians.

The Austrian plan in 1866 was to use interior lines of communication to concentrate and destroy the Prussian forces piecemeal, in classic Napoleonic form. Benedek, the Austrian commander, decided to make his stand at Sadowa, approximately 10 miles west of the Elbe River, which constituted a major obstacle. The Elbe had one permanent bridge and one pontoon bridge, which was anchored on the fortress city of Koniggratz (from which the battle takes its name). This latter bridge could provide a withdrawal route for the Austrians should it be required. In order to hold this defensive position, Benedek deployed 215 000 infantry and 750 guns.

The Prussian 1st Army made contact with the Austrian position at 0400 hrs on 3 July. The commander of 1st Army had decided to commence his attack at 1000 hrs after his troops had been rested and fed. This was over-ruled by von Moltke. A delay in attacking and fixing the Austrians might allow them to slip away before 2nd Army could encircle them. Von Moltke instead ordered 1st Army to attack immediately. Unfortunately, von Moltke had no way of knowing that the Austrians had no intention of withdrawing; this unprepared attack would play right into their hands. The battle ebbed and flowed and degenerated into a confusing morass as commanders lost control of their troops. For a time, the Prussians thought that the battle was lost, but von Moltke was unshaken. By noon, 2nd Army threatened the Austrian right; the Austrians were forced to mount costly counterattacks against massed rifle fire in order to delay the Prussians long enough to enable a withdrawal across the River Elbe. Shortly after the battle, the Austrians conceded defeat and sued for peace. Von Moltke’s doctrine had been a success.

After the war, the Prussians went back to study their own effectiveness to see if there were any lessons to be learned. As a result, they moved their artillery from the rear of its columns to the front and deployed their cavalry well forward to conduct reconnaissance. Within four years, the Prussians would be at war again. This time, with the French.