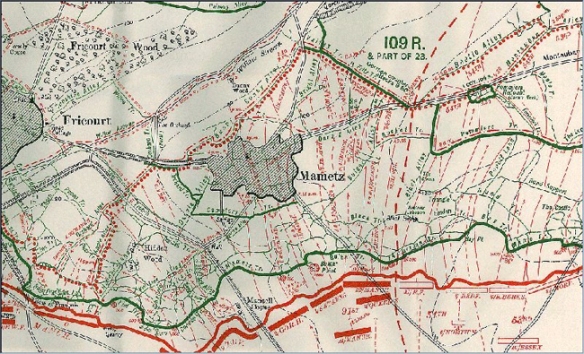

On this map of positions as they were on 30 June 1916 and during the assault next day, the British front line appears in red and the German front line in green above it. Mametz and Fricourt are strongly fortified villages immediately behind and part of the German front line complex. Mametz Wood and Contalmaison lie beyond the shallow valley of Willow Stream and just in front of the enemy’s second line system. Rawlinson’s Fourth Army plan of attack aimed at being well beyond Mametz by 2 hours and 40 minutes after the opening of the assault. Extract from British Official History, Crown Copyright.

The Somme region of France is beautiful, undulating farmland. The region takes its name from the Somme River, a pretty, meandering stream, that is known for its fishing and wildlife. The actual river is south of where the battle occurred and never became part of it. The main cities of the countryside are connected by arrow straight Roman roads. A large amount of the fighting took place around the Roman road running along a main ridge connecting the cities of Albert and Bapaume. The countryside is dotted with small French farming villages. In 1916, these villages, such as Thiepval, Mametz, Courcelette and Pozieres, gained infamous reputations. But the villages themselves had long ceased to exist; they had been torn to shreds by the massive military onslaught.

The choice of the Somme as the location from which to launch the first major British offensive of the war is puzzling. It had no particular strategic value and possessed no breakthrough potential. It is an unlikely place to imagine an army could achieve a decisive victory. The question that has perplexed military historians is: why the Somme? Calculating the men lost in this battle, more 1,200,000, only adds emphasis to the debate. There seems to be no answer to this question, other than the Somme was a useful place to launch an attack and start a war of attrition.

As the Somme battlefield lacked any particularly advantageous physical characteristics, the Germans had built a complex series of interconnecting trenches and deep redoubts across the rolling chalk hills. They took full advantage of every contour. To protect themselves from observation, the Germans generally entrenched on the down side of a slope. The trenches were deep and solid, often strategically interconnected with other switch trenches. A warren of communication and support trenches was utilized for transporting supplies, reinforcements and ammunition. The redoubt positions were often connected by tunnels coming from a variety of places in the support lines. In front of the trenches were dense belts of barbed-wire. Farms had been fortified and linked by a maze of underground works. Each position was designed to extract a great price from any attacker.

“The modern battlefield is like a huge, sleeping machine with innumerable eyes and ears and arms, lying hidden and inactive, ambushed for the one moment on which all depends. Then from some hole in the ground a single red light ascends in fiery prelude. A thousand guns roar out on the instant, and at a touch, driven by innumerable levers, the work of annihilation goes pounding on its way.

Ernst Junger, German Army

The British strategy to capture a trench works was to plaster the German position with high-explosive shells in the hope of collapsing the trench walls, killing or wounding the defenders, and cutting the extensive barbed-wire in front of the trench with shell shrapnel. At the appropriate time, the assault troops would approach the German lines as closely as possible without being hit by their own artillery fire, and at zero hour, rush and take the position. Even if the attack were successful, it did not preclude the Germans digging another trench behind the one just captured or counter-attacking to retake the one lost. In the Battle of the Somme, the Germans did both.

More often than not, the attacks on the strongly fortified German defences on the Somme proved disastrous. The artillery bombardment rarely cut the barbed-wire and the soldiers, trapped in No Man’s Land, would be cut down in swathes by the German machine-guns. Sometimes, the Germans allowed the assault troops to enter their front-line trench. Then the German artillery would blast No Man’s Land to prevent reinforcements or ammunition from reaching the newly captured position. The reinforcements would be decimated by the German barrage when crossing the open ground and the soldiers in the captured trench would be isolated. At this point, the Germans would counter-attack via communication trenches or underground subways. The German stick grenade was the weapon of choice and was a very effective killer with good range and accuracy. These defensive techniques cost the Australians heavily at Pozieres; the Canadians on the Somme learned about these tactics the hard way.

“If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are, I know where they are,

If you want to find the old battalion,

I know where they are,

They’re hanging on the old barbed-wire,

I’ve seen em, I’ve seen em,

Hanging on the old barbed-wire.”

First World War Song.

The only flaw in the German method was that the counter-attacker often suffered more casualties than the attacker. Germany could not win a war of attrition.

The Canadians arriving at the Somme could not believe the devastation. Even compared to the horrific standards of Ypres, the sights were shocking. It was their first view of total destruction; villages razed, the battlefield a lunar landscape of interconnected shell holes, destroyed trenches, sandbags spread everywhere, old equipment scattered, and thousands of bodies, decomposing in the summer sun. But they did not have much time to mull over these images of immense destruction. They were immediately put in the line in support of the Australians.

“Through a gap between two sandbags I was shown the village (Pozieres), where smoke was drifting across skeletons of trees on a torn-up mound. An uneven line of sandbags, stretching across piles of bricks and remnants of houses, faced our way… The ground between our trench and the ruins beyond was merely a stretch of craters and burnt-up grass broken up by tangled wire… The dead were lying in all conceivable attitudes; rotting in the sun… with the heat the smell had become very trying.”

Paul Maze, French Army attached British Army.

Despite serving in a secondary role, Canadian losses were considerable. Between September 4th and 7th, the 1st Canadian Division’s 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) supported the Australian Infantry attack on Mouquet Farm and other German positions north of Pozieres. The Canadian battalion suffered 349 casualties. On September 9th, the 2nd Battalion (Eastern Ontario) attacked a German trench work south of the Pozieres windmill. The attack was only a local action; one meant to improve the jump-off position for the up-coming major assault.

In this fierce action, Corporal Leo Clarke won the Victoria Cross. Clarke, and a section of bombers, were confronted by 20 Germans. Clarke attacked the attackers, emptied his revolver into them, killed four and captured another. Single-handedly, he had stopped a German attack. Clarke was one of three men from the same street in Winnipeg to win the Victoria Cross in the war. Sadly, two of the three did not survive. Leo Clarke was wounded later in the Battle of the Somme and died of his wounds. He was 24.

#

The Anglo-French armies had advanced some 10 kilometres (6 miles) at their point of deepest penetration, on a 40-kilometre (25-mile) front. Losses remain controversial. The British suffered nearly 420,000 casualties, their French allies just over 200,000. The German losses were at least 400,000 men, possibly as many as 650,000.

Although the German army did not collapse in 1916, in A.J.P. Taylor’s phrase, at Verdun and the Somme the German army ‘bled to death’. Its 1917 recruits were already in the line by the end of 1916. In spring 1917 it was obliged to withdraw its untenable front in Picardy to the prepared positions of the Hindenburg line, to liberate manpower for a renewal of the attritional struggle. Nor could it compete in the battle of matériel (materialschlacht) which the allies forced it to fight. The allied blockade was starting to impact heavily on productivity and morale on the home front. In December 1916 the new duumvirate at the head of the German army, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, intensified mobilisation with a new Auxiliary Service Law conscripting labour on the home front into war industries. The year of attrition had cost the already tired French army and nation equally dearly. Only the British emerged from the Somme with credit. The ordinary soldiers had borne the heavy sacrifice with stoicism, and after initial failure the inexperienced army had learned to fight with skill and determination. The expectation of rapid military victory disappeared. After 1916 the war became a struggle to outlast the enemy in a brutal ‘total war’. In this the allies had the upper hand.