The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was established as an independent service in March 1921, but military aviation in Australia predated World War I, and the four squadrons of the Australian Flying Corps had fought on the Western Front and in the Middle East from 1914 to 1918. In the interwar period the air force made do with limited resources; it successfully resisted attempts by the army and the navy to divide it between themselves, and it concentrated on local defense capabilities and the pioneering of civil aviation infrastructure. In 1939 Australia signed the agreement which set up the Empire Air Training Scheme (also known as the Commonwealth Air Training Plan) to provide aircrew for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in Europe, and this was to have severe long-term implications for the RAAF in Australia. Thousands of Australians served in Europe throughout World War II, and the British government demonstrated a marked reluctance to release them for return to Australia even when, in the latter part of the war, many of them were surplus to requirements.

At the beginning of the Pacific war the RAAF was small in size, suffered from a lack of training, and was equipped with obsolescent aircraft. Four squadrons were deployed to Malaya, and these were the first RAAF units to see action against the Japanese. Nos. 1 and 8 Squadrons flew Hudson bombers, while Nos. 21 and 453 Squadrons were equipped with Brewster Buffalos—and both were outclassed by the Japanese in a campaign that established the enemy’s early dominance in the air. In Australia itself there was as yet no integrated air defense system, and when the Japanese bombed Darwin in the first of a series of heavy air raids on February 19, 1942, numerous Australian and U.S. aircraft were destroyed on the ground.

When General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Australia in April 1942, he assumed control over all forces in the Southwest Pacific Command. With the arrival of General George C. Kenney in August to take command of the Allied Air Force (AAF), he established separate command and control systems for the RAAF and the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), creating RAAF Command and the Fifth Air Force. On a personal level Kenney respected his Australian counterparts and generally enjoyed good relations with the senior officers of that service. The great weakness in the RAAF was of the Australians’ own making. At the beginning of the Pacific war the chief of the Air Staff had been a British officer on detached service, Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Burnett. When he retired in May 1942, he was succeeded by Air Vice Marshal George Jones—not by Air Vice Marshal W. D. Bostock, who had been Burnett’s choice; Jones was junior in rank not only to Bostock but also to seven other senior officers on the air force list. Bostock became air officer commanding RAAF Command and was responsible to Kenney for RAAF operations in the Southwest Pacific Command, while Jones had administrative responsibility for the air force. Relations between the two were poisonous, and the corrosive effect this had on the RAAF as a whole played itself out for the remainder of the war. But ill will among senior officers had been a feature of the interwar air force as well.

As a result of the divisions at the top, the RAAF generally failed to develop a strategic doctrine acceptable to the United States, which in turn prejudiced attempts to acquire frontline aircraft for the RAAF from the Americans, which in its turn meant that Australian squadrons were relegated to lower-priority roles and tasks. Senior command postings to No. 9 Operational Group in 1943 reflected the feuding in the high command and further undermined U.S. confidence in the RAAF’s capabilities.

The Australian government was aware of the problem but lacked sufficient resolve to do anything about it. This high-level rancor and the far smaller size of the RAAF meant that the air service was fated to play a subordinate role in the Pacific war. Nonetheless, the RAAF expanded to impressive size and strength: At its peak in August 1944 it numbered 182,000 personnel, which by war’s end had declined to 132,000 as the government partly demobilized in response to the manpower crisis. In August 1945 the RAAF fielded fifty squadrons and some six thousand aircraft (3,200 operational and the rest trainers).

In June 1944 the air forces in the theater were reorganized, with Kenney announcing the formation of the Far East Air Force comprising the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces, both American. This meant that the Allied Air Force, of which he retained command, henceforth comprised only Australian, New Zealand, and Dutch East Indies squadrons, although U.S. squadrons could be attached to the AAF for specific tasks. The AAF, like its army counterparts, was assigned “mopping-up” duties against bypassed enemy forces in the islands to Australia’s north while the U.S. forces proceeded to the reconquest of the Philippines and the contemplated invasion of the Japanese home islands.

First Tactical Air Force (1st TAF) was formed in October 1944 from No. 10 Operational Group and began operations against Japanese positions from bases on Morotai in November. Dissatisfaction with their role grew among the squadrons, and in April 1945 a group of eight senior officers attempted to resign in protest. The “Morotai mutiny” prompted the removal of the commander of the 1st TAF and an inquiry which confirmed that decision. When Jones threatened disciplinary action against the eight, Kenney—who had spoken to the officers concerned and concluded that they had acted in good faith— declared that he would appear in their defense in any court martial.

In June 1945 with a strength of 21,893, of all ranks, the 1st TAF supported the Australian landings in Borneo and continued to fly against Japanese targets elsewhere in the Dutch East Indies until the war’s end. In the war against Japan the RAAF suffered some two thousand casualties—killed, wounded, and prisoners of war.

The performance of the RAAF in the Pacific war was disappointing, in that it failed to conduct a leading role in the Southwest Pacific Command, its primary theater in the defense of Australia. The weakness in senior command explains much of this failure, and blame both for creating and then for sustaining this situation must lie with the government of the day. On the other hand, by 1945 the RAAF had grown into a large and capable organization, with many combat-experienced aircrew and officers who had held senior command and staff positions. Although aircraft acquisition had been a difficult problem in the first half of the war because of competing priorities elsewhere, by 1945 the RAAF possessed large numbers of modern aircraft and the capability to support them. The failures at the top were not matched by a lack of performance elsewhere in the organization.

FURTHER READINGS

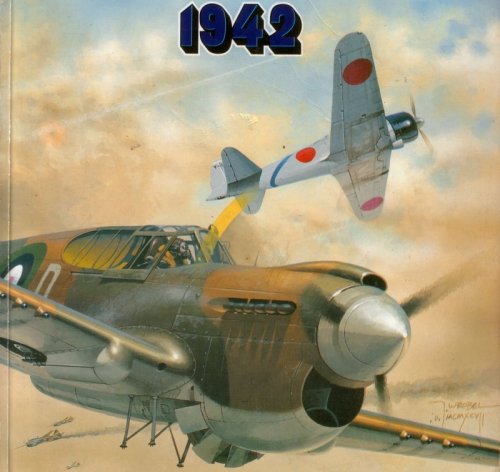

Gillison, Douglas. Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942 (1962).

Odgers, George. Air War against Japan 1943–45 (1957).

Stephens, Alan. Power Plus Attitude: Ideas, Strategy and Doctrine in the Royal Australian Air Force 1921–1991 (1992).