The tactics of the Chouans have been described by many eyewitnesses. Thus Joseph Clemenceau:

They fought without order, in squads or crowds, often as individual snipers, hiding behind hedgerows, spreading out, then rallying, in a way that astonished their enemies, who were entirely unprepared for these manoeuvres; they were seen to run up to cannons and steal them from under the eyes of the gunners, who hardly expected such audacity. They marched to combat, which they called aller au feu, when they were called by their parish commandants, chiefs taken from their ranks and named by them, centurions, so to speak, who had more of their confidence than did the generals chance had given them; in battle as at the doors of their churches on Sunday, they were surrounded by their acquaintances, their kinfolk and their friends; they did not separate except when they had to fly in retreat. After the action, whether victors or vanquished, they went back home, took care of their usual tasks, in fields or shops, always ready to fight.

Hoche, in a letter to Aubet-Dubayet, noted that the Chouans had friends and agents everywhere and always found food and ammunition whether it was given voluntarily or taken by force. Their principal object was to destroy the civilian authorities, and to that end they intercepted convoys, assassinated government supporters, disarmed Republican soldiers and even tried to foster unrest among the town dwellers. Their tactics were to disperse silently behind hedges, to shoot from all directions, and at the slightest hesitation on the part of the Republican forces to attack them while shouting their war cries. Encountering stiff resistance, they would retreat and renew their attack on another occasion. A Chouan leader addressed the following warning to the Republican authorities:

The Chouans will demolish all the bridges, intercept all communications, destroy all mills which they do not need, cut the knuckles of all cows and the hocks of the horses employed in transporting supplies, kill every state employee performing his duty, kill everyone obeying requisitions; they will force the population under threat of the death penalty to follow them . . . they will not lower their arms until they have made France a great cemetery.

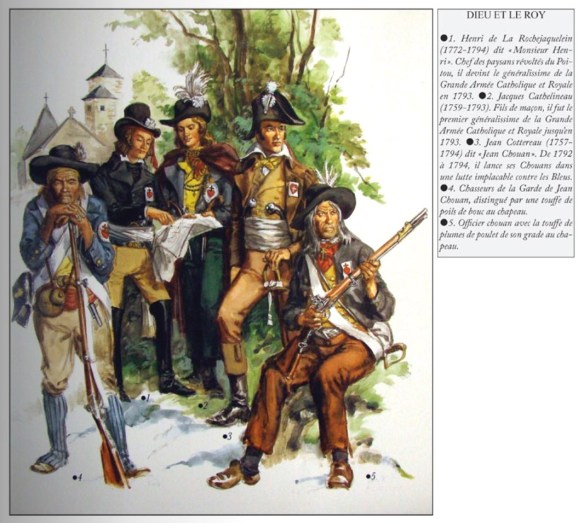

The Chouans were organized on a local basis with assembly points in every village. The peasants kept their own arms and brought food along for three to four days when they went into action. Some of them wore uniforms — green coats and pantaloons with red waistcoats and a white cockade. They frequently attacked at night and they were past masters at ambushing small detachments in a country which favored such operations. They were less inventive when fighting involved larger units on each side. Kleber observed that their plan of battle was always the same:

It consists in greatly extending their front so as to envelop us and throw disorder in our ranks. . . . When they advance on us they generally take care to dispose their army in three columns whatever the character of the ground . . . their right column is always the strongest and made up of the best men. The center column, strengthened by a few cannons, moves forward, while the other two open up into skirmish lines along the hedges, but the main effort almost always comes from the right.

Republican commanders noted that it was the practice of the Chouans not to attack unless their force was greatly superior. When forced to retreat, the Chouans would rally at a distance of a few miles and immediately counterattack the unprepared enemy. On certain occasions they would appear on the battlefield with Republican hostages in front of them; at other times they would wear Republican uniforms so as to surprise the enemy. They were men hardened by long winter nights, men who could jump over hedges and ditches, could see in the dark and hear the slightest noise.

In the jaundiced view of their Republican enemies, the Chouans were little better than untamed animals. In actual fact their approach was quite sophisticated, when engaging in psychological warfare, for instance. Early in the war the Catholic army was given orders not to rob and to show leniency toward prisoners. These were released and given special passes on condition that they gave their word of honor not to fight again in the Vendée. Among the Chouans there were detachments of French, Swiss and German deserters; these were not very strong, but their very existence helped to demoralize the Republicans. In a leaflet signed “Les Brigands,” the Chouans addressed the Republican soldiers as “nos amis et frères.” The city dwellers who had grown rich (it said), were those culpable for the bloodshed. The Republican soldiers were mere dupes, exploited (like the Chouans) by the common enemy. On more than one occasion the Chouans attacked, caught, and executed gangs of bandits to dissociate themselves from criminal elements and to help the peasants who had suffered from them. In the end the revolt of the Chouans was put down because the Republic concentrated vastly superior forces against them and used effective counterguerrilla tactics both on the military and the civilian level, A network of entrenched camps was established which the Chouans could not bypass. The Republican soldiers systematically combed the area, seizing the peasants’ cattle until they surrendered their arms. All suspects were arrested in the course of these operations, which were carried out in great secrecy with the help of the local police. In the instructions to his officers, Hoche always stressed the importance of establishing a good intelligence service and of deceiving the enemy about their intentions.

But Hoche also understood that this war could not be won by arms alone. He insisted on strict discipline on the part of his troops; severe punishment threatened those who assaulted civilians and did not respect their property. In an appeal to the civilian population, he announced that, unlike the rebels, the soldiers of the Republic would not answer cruelty with cruelty, terror with counterterror: “You will find in these soldiers zealous protectors just as the brigands will find in them implacable enemies. Peaceful and honest citizen, stop believing that your brothers want your ruin; stop believing that the fatherland wants your blood, it merely wants to make you happy through its beneficial laws.” In his correspondence with Paris, Hoche emphasized the importance of treating the clergy well. He saw the priests as the main instrument for regaining the confidence of the population. They could be made to understand that the continuation of the Chouannerie meant war without end, with all the human suffering and the material losses that involved. A victory by the Republic, on the other hand, would restore peace and religious tolerance. Hoche’s moderate course of action did not make him any more popular among the Chouans, while in Paris he was suspected of being too soft and thus ineffectual. A tribute was paid to him only in 1796 after the pacification had been completed, when Carnot, the president of the Directoire, expressed the thanks of the Republic to the “Army of the Ocean” and its commander.

The Chouans received some supplies from England but this assistance was at no stage decisive. Of the nobles who had left France, only few were inclined to return and fight. Those who did despised the peasants and their conduct of war. They wanted to fight according to time-honored tradition — and were quickly wiped out by the armies of the Republic. Since the Chouans did not hold any major port, supplies were neither substantial nor regular and in the last resort they could rely only on their own resources. The Chouans had no guerrilla doctrine; they were simply adapting their war to local conditions and, after their initial setbacks, fought the only way they possibly could. The Russian partisans under Denis Davydov were regular soldiers, engaged in raids to the enemies’ rear. The Spanish guerrilla fighters received substantial help from Wellington and the various local juntas, which also provided political leadership. The Chouans, in contrast, had no government, no political advisers. Of all the early guerrilla movements, it was the most spontaneous, the most isolated, and thus, in many ways, the “purest” specimen of the lot.