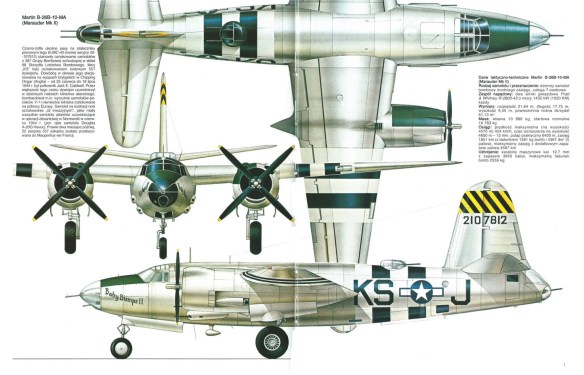

Its contemporary, the Martin B-26, familiarly called The Maurauder, was an all metal monoplane with a tricycle landing gear. The craft was powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial engines in nacelles slung under the wing, driving two four-bladed propellers.

Slightly faster than the B-25, the Maurauder’s relatively small wing area and more powerful engines made it challenging to fly. It was not a craft for novice pilots, and when inexperienced ones sat in its cockpits, the accident rate mounted. The number of crashes at MacDill Field in Florida — the chief training base for 26s — rose accordingly. A catch phrase was “One a day in Tampa Bay,” and flight crews gave the plane colorful nicknames, such as Widowmaker, Martin Murderer, Flying Coffin, Sky Prostitute (fast with no visible means of support, referring to its small wings), or Baltimore Whore, a reference to the home city of Martin Aircraft Inc. where the ships were built.

The Maurauder was used mostly in Europe and the Mediterranean and also saw action in the Pacific. By the end of the war, it had flown more than 110,000 sorties, dropped 150,000 tons of bombs, and had been used in combat by British, Free French, and South African forces in addition to U. S. units.

Adolph Hitler had been Chancellor for less than three years when he announced he was reconstituting Germany’s armed forces. Among the revisions was creation of a separate air force named the Luftwaffe, commanded by General Hermann Goring. By March, 1935, the Luftwaffe was as strong as the British Royal Air Force.

In 1939, aviation forces in the U.S. were still a part of the army and miniscule if compared with those of either Germany or Britain. Yet in America, General Henry “Hap” Arnold, assistant chief of the Air Corps and a devotee of theories expounded by the Italian Doughet and General Mitchell, had eked out approval for development of larger planes capable of offensive bombing.

Boeing Aircraft, a fledgling company in Seattle, Washington, had secured in 1918 a contract to build small airplanes designed for mail service. Arnold kept pressing and was able to convince that company to build larger planes. In 1934, Boeing had on its drawing boards plans for a four-engine bomber. The next year, 1935, the company brought out Boeing Model 299, which made its maiden flight near the end of July. A newspaper reporter for the Seattle Times described the ship as a “Flying Fortress,” and that became its common name.

The Army ordered a baker’s dozen of these prototypes in January of 1936. Ostensibly, the ships were to be used in the nation’s defense, but the B-17 also vindicated the doctrine of strategic bombing. The initial order for the four-engine behemoths was received just thirty-three days before Billy Mitchell died, a sick and broken man in a New York hospital on February 19, 1936.

Tooling up for production of B-17s was a big gamble for Boeing’s little company, and its hopes for winning a contract for more planes fluttered when an early Model 299 crashed on take-off. Fortunately, investigation revealed that the aircraft had attempted the take-off with its controls locked, so safety of the ship’s design was not suspect.

Orders for the B-17 mounted, and Boeing teamed up with the Douglas and Lockheed Aircraft companies to meet the demand. Newer models were equipped with turbocharged engines providing faster maximum speeds and a higher service ceiling. With these changes, a Flying Fortress could reach an altitude of thirty-six thousand feet, had a ferry range of 3,600 miles, and a top indicated air speed of 213 miles per hour. B-17Ds and B-17Es, later models, were given self-sealing fuel tanks and revised armament.

The B-17E was truly a Flying Fortress, armed with one .30 caliber machine gun in the nose and twelve .50 caliber other ones for defense. Modifications of this model would replace the .30 caliber gun with a chin turret with twin .50 caliber guns below the bombardier’s compartment. Such improvements meant better defense against head-on attacks from the Luftwaffe.

From Britain, more than from anywhere, came tales of indestructible B-17s, flown by intrepid crews. An example displaying both phenomena was the B-17 with Memphis Belle painted on its fuselage. From November 1942 until May 1943, this plane and its crew flew twenty-five missions over Nazi-occupied Europe, taking terrible beatings from both flak and fighters. Riddled by bullets, holed by flak bursts, the Belle returned from one mission missing most of its tail, and from another with one wing so badly shredded it had to be replaced. Five of the Memphis Belle’s big engines had to be replaced in the more than 20,000 miles of its twenty-five combat missions. Her crew dropped over 60 tons of bombs on Nazi targets and was credited with shooting down eight enemy fighters, five probables, and a dozen more damaged. With twenty-five missions completed, under orders the Memphis Belle and its crew flew back to America to tour the country, accepting acclaim not only for their own accomplishments but for deeds of their comrades.

From bases in England and later ones in Africa, Italy, and the Pacific, B-17s bombed targets of the two enemies, Germany and Japan. By the war’s end, a total of 12, 731 Fortresses had been built, and an even larger one, the Superfortress, had just become operational.

America’s other four-engine bomber during WW II was the Liberator, the B-24 produced by Consolidated Aircraft. First flown in December 1939, early models were designated LB-30A and sent to Britain. As war threats came closer to America via attacks on Atlantic shipping, the U.S. Army Air Corps began ordering B-24s in June 1941.

A little larger and slighter faster than the B-17, the Liberator could carry loads over a longer distance. B-24s flew in every theater of the war: North Africa, England, Italy, Burma, China, Alaska, Australia, and island hopped across the Pacific. Liberators were flown by twelve Army Air Forces and a dozen Navy squadrons.

The B-24 had a wing span of 110 ft., compared with the 103 ft. 9 in. of the B-17. The wing’s cross section was shaped like a raindrop and mounted atop the fuselage. The wing provided good lift, and the ship had a fuselage sixty-six feet long and eighteen feet high. Without a load, the Liberator weighed 32,505 lbs. Its weight with a full bomb load was 60,000 pounds. The ship could reach an indicated air speed of slightly more than 300 mph. with a range of 2,850 miles and fly as high as 32,000 ft.

The most distinguishing feature of the Liberator was its twin rudders. Each of its four propellers was as large as a full-grown man, and it had a tricycle landing gear with one wheel under the nose and two bigger ones under the wings. Its four engines were usually Pratt & Whitney, each rated at 1,200 horsepower, and each engine was equipped with a turbo supercharger that increased the mass air charge of the internal combustion engine while compensating for the lower air density of air at high altitudes.

The bombardier-navigator compartment in the nose of the 24 was more cramped than that of the 17, but the ship had two bomb bays, each of which would match the capacity of the B-17’s single one. The bomb doors were of the roll-up type, thus eliminating the buffeting caused by standard doors that opened into the air stream below the fuselage.

B-24s were called Box Cars by crews from their rival B-17s. Other detractors referred to them as Garbage Scows With Wings, Flying Brick, Old Agony Wagon or even more demeaning names. On the ground, the B-24 was an ungainly-looking ship, but airborne with capable, well-trained crews it carved an ineradicable niche in air warfare. The Eighth Air Force in England and the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy flew both B-24s and B-17s.

B-24s are remembered as ships which bombed Rome in July 1943 and a month later carried out the historic low-level attack on Ploesti oil refineries, a raid in which 57 planes with eight to nine crew members were lost.226

Notwithstanding its combat record in Europe, the major and unchallenged contributions of Liberators to America’s wartime operations were in the Pacific. In January 1942, Liberators were first flown in action against Japanese held islands. For more than two and a half years, B-24 crews bombed enemy bases, ammunition dumps, and oil storages. By 1943 in the Pacific, Liberators had replaced Fortresses and become work horses for the U.S. Air Corps in its fight against Japan.

The U.S. bombing record could not have been achieved without such aircraft, for costs in lives of young men were high, and squadrons would suffer horrendous losses before perseverance and determination would pay off in final victory.