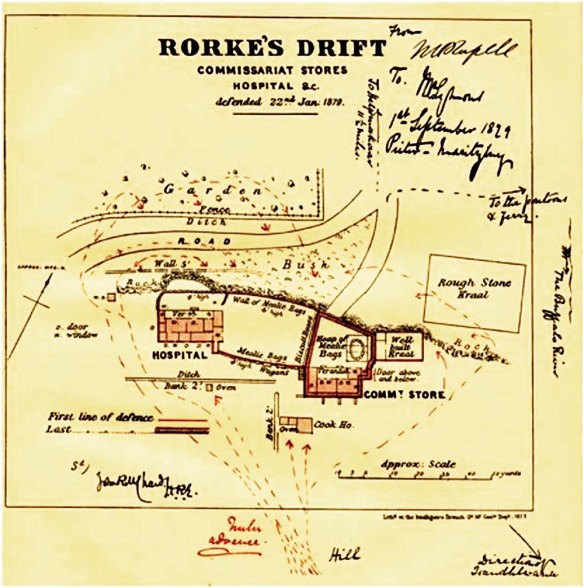

Lieutenant Chard’s famous drawing of the Rorke’s Drift battle, showing the main thrusts of the Zulu attack.

ANGLO ZULU WAR HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Under cover of the dark, the bushes and the long grass, the Zulus were now able to get within 25 yards of the hospital without being seen. From this point, in parties of fifteen to twenty, they again attacked the end room of the hospital. Many times, seven or eight at least, they began to be a dangerous nuisance to the defenders. Lieutenant Bromhead, collecting a few men together, had to drive one persistent group off with a bayonet charge. Then the Zulus would retire, and in chorus would shout and strike their shields. The soldiers cheered in answer and kept up a steady rate of fire. Initially, there was plenty of ammunition but it was quickly realized by the officers that too much was being wasted.

The Zulus at last smashed their way into the far end of the hospital but only after some thirty of the patients were rescued by their able-bodied colleagues. Most of the escaping patients were pushed and pulled through a window at the far end, which opened onto the yard next to the main British defensive wall. The Zulus now set fire to the hospital, probably from one of the houses’ many oil lamps used to illuminate the hospital after dark. The roof thatch was still damp from the earlier rain, though it would burn steadily for several hours. By its light the soldiers were enabled to see the Zulus better, and many were shot down before they retreated to better cover. After a pause, encouraged or commanded by a chief who shouted his orders from the hillside, the Zulus repeated their attack. The fighting in places became hand-to-hand over the mealie sacks, with the Zulus using their assegais as stabbing weapons against the soldiers’ bayonets. Directly a soldier showed his head over the parapet to get a shot, he was thrust at. On several occasions the leading Zulus actually seized the bayonets and tried to wrench them off the rifles.

The defenders then fell back on an inner defence consisting of another 4-foot high wall of biscuit boxes stacked upon each other that extended across the yard from the commissariat store, and formed part of a second line of defence, including the store and an open space round it, and extending as far as an adjacent cattle kraal, all of which formed part of the final defence position. This second line of defence was not resorted to until the fire from the Oscarsberg, which took the defenders of the mealie-bag barricade in flank and rear, together with the burning of the hospital, had rendered the first line of defence untenable. This second line of defence was never assaulted by the Zulus at close quarters, unlike the outer barricade of mealie bags. From this small fortified position, about the size of a tennis court, the soldiers would hold their positions until morning.

As the night wore on both sides were aided by the light of the burning hospital. This guided the Zulus’ fire from the Oscarsberg until Chard gave the order to fall back upon the second line of defence. To avoid hand-to-hand fighting, they established themselves behind the outer wall of the cattle kraal within 10 yards of the inner wall still being held by the soldiers. The rifle fire from the mealie-bag redoubt and the biscuit-box rampart was fatal to any Zulu standing still, even for a moment; thanks to the light from the burning hospital they presented the soldiers with an easy target.

After midnight the sporadic but forceful Zulu attacks slackened, but continued intermittently through the small hours until 4.00 am. The last British shot was aimed at a Zulu who was trying to fire the thatch of the store. The Zulus were clearly more exhausted than the British; not only had they run from Isandlwana, they had been without food for two days and had last drunk water when they crossed the river some nine hours earlier. Their attacks had stopped but their marksmen continued to fire into the British position from the safety of the Oscarsberg. The final flickering from the remains of the burning hospital died out at about 5.00 am and thereafter there was nothing to indicate a Zulu presence. Not knowing what the Zulus were doing under the cover of darkness and fearing an attack at any moment, Chard ordered his weary men to remain at their posts. Shortly after 5.15 am, the early dawn lightened the sky and the British realized that the only Zulus in sight were the dead and wounded. The main Zulu force had vanished.

The defeated Zulus had steadily made their way back to the drift and after quenching their thirst had assembled on the far bank of the Buffalo River. It was at this stage that they first noticed, some 2 miles off, the approaching column led by Lord Chelmsford. The column was retracing the route it had taken a few days earlier and was approaching the drift from the direction of Sihayo’s stronghold. Not wishing to engage the British, either as soldiers or ghosts, the Zulus turned right and followed the riverbank, presumably to avoid further conflict. It is uncertain whether the Zulus knew that Chelmsford and a portion of his force had survived. Zulu folklore explains that the distant column ‘looked like ghosts’ coming through the early morning mist thrown up by the river. The departing Zulus genuinely believed the whole of Chelmsford’s column had died at Isandlwana and many would have thought they were seeing the ghosts of vanquished British soldiers returning to Rorke’s Drift. The theory is credible. In any event, Chelmsford’s direct approach surprised the retreating Zulus; indeed, both groups passed each other at a distance of 400 yards. Chelmsford’s men had but twenty rounds of ammunition each and the Zulus were exhausted, so neither side had any enthusiasm for a fresh fight.

It was not until dawn that the lookouts at Rorke’s Drift could confirm the disappearance of the Zulus from the hill, and it was not for another two hours that Chelmsford’s column could be seen approaching from the drift. The sight was greeted by a ringing round of cheers. Within the outpost, the scene was disturbing. The whole area was awash with pools of congealed and smeared blood, which bore witness to the death throes of both British and Zulu warriors. The area was littered with dead and dying Zulus; empty ammunition boxes were strewn around along with torn cartridge packets and piles of spent ammunition cases. The remnants of discarded red army jackets lay in the dust. They had been torn apart by the soldiers as improvised binding for their red-hot rifle barrels in the desperate attempt to save their hands from burning as they fired. The whole inner area was covered in trampled maize that had poured from the damaged sacks along the walls, walls that had successfully borne the brunt of the Zulu attacks. The heat from the burnt-out hospital gradually abated and, not deterred by the smell of cooked human flesh, the defenders found the charred bodies of the patients who had died within its walls. As there were many more charred bodies than the defenders had expected, they naturally presumed that these were Zulus, killed either by the defenders or by the hospital fire. During that same day, Lieutenant Curling RA returned to Rorke’s Drift, and that night he wrote:

The farmhouse at Rorke’s Drift was a sad sight. There were dead bodies of Zulus all round it, in some places so thick that you could hardly walk without treading on them. The roof had been taken off the house as it was liable to be burnt and the wounded were lying out in the open. A spy was hanging on one of the trees in the garden and the whole place was one mass of men. Nothing will now be done until strong reinforcements arrive and we shall have much bloodshed before it is all over.

The killing of seriously injured Zulus around the mission station then commenced. It was an act reciprocated by the Zulus, who killed any British soldiers left wounded at Isandlwana. Indeed, it was a fate well understood by both sides. Regrettably, the subsequent British action of killing exhausted Zulus or those who had gone into hiding well away from the mission station was to be more disturbing, even in the climate of such total warfare. Comment on the Zulus’ fate was deliberately omitted from official reports to prevent the gruesome details being published in the British press. Such merciless mopping-up operations were, nevertheless, deemed necessary by those present and would be repeated as a matter of military policy by the British after each of the remaining battles of the Zulu War, especially after their victories at Gingindlovu, Kambula and Ulundi. The total number of Zulu dead from Rorke’s Drift will never be known. The most likely figure of immediate Zulu casualties would tally at about 500, with probably another 300 or more being accounted for during the subsequent securing of the surrounding area. By comparison, British casualties were comparatively light, with fifteen men killed and one officer and nine men wounded (two mortally). The subsequent publication of details of indiscriminate and wholesale killing of Zulu survivors in hiding or fleeing from the battlefield was later to cause the military authorities much embarrassment.

The engagement at Rorke’s Drift was initially viewed by the British military in South Africa as nothing more than a skirmish, and, in military terms, they were correct; it was obvious to those present that a single concerted attack by the Zulus would easily have overwhelmed the small garrison. The praise and fame immediately heaped on the defenders increasingly rankled with many who saw the unexpected status of those present elevated to that of popular heroes. Even General Wolseley wrote on the matter:

It is monstrous making heroes of those who saved or attempted to save their lives by bolting or of those who, shut up in buildings at Rorke’s Drift, could not bolt, and fought like rats for their lives which they could not otherwise save.

Major Clery was one of Chelmsford’s staff officers who commented on the action:

Reputations are being made and lost here in almost comical fashion.

The homecoming for the Zulus was no better. It was as a result of their failed action at Rorke’s Drift that Dabulamanzi’s returning warriors were chided and mocked. Zulu folklore holds that it was said that ‘you marched off, you went to dig little bits with your assegais out of the house of Jim, that had never done you any harm.’ Zulu folklore also relates that the surviving warriors who had attacked Rorke’s Drift were seriously dejected by their failure and worse was to come. The retreating warriors were jeered and mocked by the villagers through whose homesteads they passed. The gist of the baiting calls included ‘shocking cowards’ and ‘you’re just women – running away for no reason at all, just like the wind’.