That universal work-horse of all the minor, and major, wars since 1945 played little or no part in World War II. Helicopters did exist before the war – Hanna Reitsch flew one of the first practical helicopters in February 1938. This was the Focke-Achgelis Fa61; it was not by any means the first helicopter, nor was Hanna Reitsch its first pilot, but the series of remarkable flights she made gained worldwide publicity for the very simple reason that they took place indoors.

The Fa61 had, during 1937, established several international helicopter records, including the altitude record of 8002 feet and a speed record of 76.15 mph. The record-breaking pilot was Edwald Rohlfs, but in the atmosphere of growing distrust of Nazi propaganda, the reports of the records had been muted and, to gain the international notice which the Germans desperately wanted, a more sensational demonstration was required. According to Hanna Reitsch, who has survived more flying adventures than almost any other pilot, it was General Udet himself who thought up the brilliant propaganda coup that was to force the world to notice the achievements of the German helicopter. He persuaded her, at that time not only an attractive young woman, but also a noted international glider champion, to learn to fly the Fa61 and to demonstrate it for fourteen successive evenings inside the huge Deutschlandhalle in Berlin during the 1938 German Motor Show. Each evening she flew the small helicopter under perfect control before audiences of 20,000, including no doubt the military attachés. It was a sensational début, for at that time most rotary-wing aircraft were autogyros, which are incapable of vertical flight.

The Fa61 was a true helicopter, though by modern standards crude. It was basically the fuselage of a Focke-Wulf FW44 Stieglitz (Goldfinch) trainer biplane, complete with its original 160-hp Siemens radial engine, which drove two 3-bladed rotors carried on outriggers. The small propeller in the conventional position was fitted simply to cool the engine, but it flew well enough. After the Deutschlandhalle flights, a second Fa61 ascended to 11,243 feet, a record that was to stand for some time.

German wartime helicopters included the Flettner F1282 Kolibri (Hummingbird). This was the first military helicopter and it was the only one to be used operationally during the war years. About twenty were delivered to the German Navy, being used principally on board ships for antisubmarine patrols and communication flights, mainly in the Aegean and the Mediterranean.

The F1282 first flew in 1940 and used the intermeshing ‘eggbeater’ technique of two rotors to eliminate torque effects. It was powered by a single 140-hp Siemens-Halske radial engine and had a top speed of 90 mph. It could easily operate from ships and was entirely successful, though like many early helicopters it was limited by the very small offensive load it could carry. Nevertheless, 1000 were ordered for the German Navy in 1944, but by then Allied bombing made the production impossible.

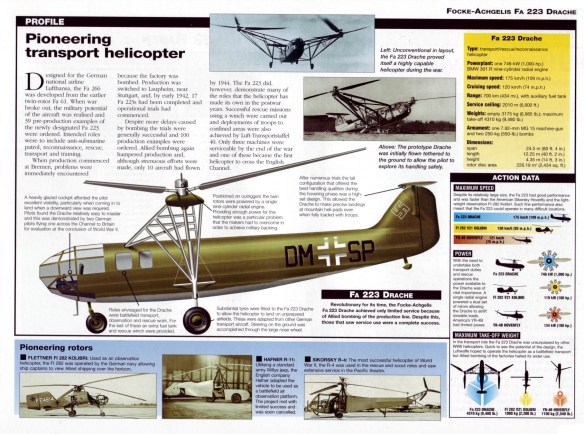

The most advanced wartime helicopter was the Fa223 Drache (Kite). This was a very large machine which could carry at least six people and lift a heavy load. Designed primarily for communications, it pioneered the role of the helicopter as an airborne crane: a short reel of German wartime film in the Imperial War Museum Archives shows an Fa223 lifting the fuselage of a crashed Me109. 400 Draches were ordered, but again Allied bombing prevented production, only a dozen or so being completed. In 1945 a surviving Fa223, flown by a German crew, was tested at the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment at Beaulieu airfield in Hampshire, where it was subsequently destroyed in a crash.

At Beaulieu yet another remarkable German rotary-wing aircraft was test-flown after the war: the Fa330 Bachstelze (Wagtail). This small machine was not, strictly speaking, a helicopter but a rotary-wing kite. It was carried in dismantled form in two watertight compartments on the deck of Type IX ocean-going U-boats; its function was to provide a high vantage point for spotting targets in the Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic, where isolated ‘independents’ – single merchant ships – sailed these little frequented waters without escorts for protection. The low height of a surfaced U-boat’s conning tower strictly limited the range of search, but, towed by the U-boat, the Bachstelze could climb to some 500 feet, enabling its pilot/observer greatly to extend the submarine’s field of vision. A telephone cable connected the pilot to the U-boat’s commander and, on sighting a ship, he was in theory winched down to the deck. However, if the vessel reported was thought to be a warship, or if an aircraft appeared, the submarine would crash-dive and the unfortunate pilot had then to jettison the rotors, which flew upwards, deploying a parachute as they departed which enabled him to descend into the sea still seated in the simple tubular fuselage. He then released his seat straps and, in the cynical words of a wartime report, ‘drowned in the normal way’. Two Fa330s survive in England: one in the Science Museum, the other in store for the RAF Museum.

A little-known British rotary-wing development was the Rotajeep, one of a number of proposals tested by the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment from 1942, for utilising rotating wings to enable military loads, ranging from a single soldier to a tank, to be towed into battle with the Airborne Forces. The Rotajeep was a standard US Army Jeep with the addition of a simple fuselage and tail unit and a pylon which carried a folding 2-bladed rotor. Test flights were made in 1942, when the Rotajeep was towed behind a Whitley at speeds up to about 150 mph; although the tests were reasonably successful, serious problems of stability arose and no free flights were attempted. Had the problems been overcome and the trials continued, the towing aircraft would have released the Rotajeep which would have drifted down like a sycamore leaf to land at a mere 36 mph. Safely arrived, the crew could then fold the rotors, start the jeep’s engine and drive into action. The Rotajeep idea was not developed. Nor was a similar proposal – the addition of no less than 155-ft rotors on to tanks; one was actually built but, perhaps wisely, not flown.