Persian King Darius’s successors showed markedly less interest in their Egyptian satrapy. They ceased even to pay lip service to the traditions of Egyptian kingship and religion. Commercial activity began to decline, and political control slackened as the Persians focussed their attention increasingly on their troublesome western provinces and the “terrorist states” of Athens and Sparta. Against such a backdrop of political weakness and economic malaise, the Egyptians’ relationship with their foreign masters started to turn sour. A year before Darius I’s death, the first revolt broke out in the delta. It took the next great king, Xerxes I (486–465), two years to quell the uprising. To prevent a recurrence, he purged Egyptians from positions of authority, but it could not stop the rot. As Xerxes and his officials were preoccupied with fighting the Greeks at the epic battles of Thermopylae and Salamis, members of the old provincial families across Lower Egypt began to dream of regaining power—a few even went as far as to claim royal titles. After less than half a century, Persian rule was beginning to unravel.

The murder of Xerxes I in the summer of 465 provided the opportunity and stimulus for a second Egyptian revolt. This time, it was led by Irethoreru, a charismatic prince of Sais following in the family tradition, and the revolt was not so easily suppressed. Within a year, he had won supporters across the delta and further afield; even government scribes in the Kharga Oasis dated legal contracts to “year two of Irethoreru, prince of the rebels.” Only in the far southeast of the country, in the quarries of the Wadi Hammamat, did local officials still recognize the authority of the Persian ruler. Sensing the popularity of his cause, Irethoreru appealed to the Persians’ great enemy, Athens, for military support. Still smarting from the vicious destruction of their holy sites by Xerxes’s army two decades earlier, the Athenians were only too glad to help. They dispatched a battle fleet to the Egyptian coast, and the combined Greco-Egyptian forces succeeded in driving the Persian military back to their barracks in Memphis, and in keeping them pinned down there for many months. But the Persians were not going to give up their richest province so easily. Eventually, by sheer force of numbers, they broke out of Memphis and began to take the country back, region by region. After a struggle lasting nearly a decade, Irethoreru was finally captured and crucified as a grim warning to other would-be insurgents.

The Egyptians, however, had enjoyed their brief taste of freedom and it was not long before another rebellion broke out, once again under Saite leadership, and once again with Athenian support. Only the peace treaty of 449 between Persia and Athens brought a temporary halt to Greek involvement in Egyptian internal affairs, and allowed the resumption of free commerce and travel between the two Mediterranean powers. (One beneficiary of the new dispensation was Herodotus, who visited Egypt sometime in the 440s.) Yet Egyptian discontent did not evaporate. The prospect of another major uprising looked certain.

In 410, civil strife erupted across the country, with near anarchy and intercommunal violence flaring in the deep south. At the instigation of the Egyptian priests of Khnum, on the island of Abu, thugs attacked the neighboring Jewish temple of Yahweh. The perpetrators were arrested and imprisoned, but, even so, it was a sign that Egyptian society was in upheaval. In the delta, a new generation of princes took up the banner of independence, led by the grandson of the first rebel leader of forty years before. Psamtek-Amenirdis of Sais was named after his grandfather but also bore the proud name of the founder of the Saite Dynasty, and he was determined to restore the family’s fortunes. He launched a low-level guerrilla war in the delta against Egypt’s Persian overlords, using his detailed local knowledge to wear down his opponents. For six years, the rebellion continued unabated, the Persians discovering the impotence of a superpower against a determined uprising with popular local support.

Finally the tipping point came. In 525, Cambyses had taken full advantage of the pharaoh’s death to launch his takeover of Egypt. Now the Egyptians returned the compliment. When news reached the delta in early 404 that the great king Darius II had died, Amenirdis promptly declared himself monarch. It was only a gesture, but it had the desired effect of galvanizing support across Egypt. By the end of 402, the fact of his kingship was recognized from the shores of the Mediterranean to the first cataract. A few waverers in the provinces continued to date official documents by the reign of the great king Artaxerxes II—hedging their bets—but the Persians had troubles of their own. An army of reconquest, assembled in Phoenicia to invade Egypt and restore order to the rebellious satrapy, had to be diverted at the last moment to deal with another secession in Cyprus. Having thus been spared a Persian onslaught, Amenirdis might have been expected to welcome the renegade Cypriot admiral when he sought refuge in Egypt. But instead of rolling out the red carpet for a fellow freedom fighter, Amenirdis had the admiral promptly assassinated. It was a characteristic display of Saite double-dealing.

Despite such ruthlessness, Amenirdis did not long enjoy his newly won throne. By seizing power through cunning and brute force, he had stripped away any remaining mystique from the office of pharaoh, revealing the kingship for what it had become (or, behind the heavy veil of decorum and propaganda, had always been)—the preeminent political trophy. Scions of other powerful delta families soon took note. In October 399, a rival warlord from the city of Djedet staged his own coup, ousting Amenirdis and proclaiming a new dynasty.

To mark this new beginning, Nayfaurud of Djedet consciously adopted the Horus name of Psamtek I, the most recent founder of a dynasty who had delivered Egypt from foreign rule. But there the comparison ended. Ever wary of Persian reprisals, Nayfaurud’s brief reign (399–393) was marked by feverish defensive activity. His most significant foreign policy was to cement an alliance with Sparta, sending grain and timber to assist the Spartan king Agesilaos in his Persian expedition.

In 393, when Nayfaurud’s heir Hagar became king, a native-born son succeeded his father on the throne of Egypt for the first time in five generations. Despite having a name that meant “the Arab,” Hagar was proud of his Egyptian identity and was determined to fulfill the traditional obligations of monarchy. A favorite epithet at the start of his reign was “he who satisfies the gods.” But piety alone could not guarantee security. After barely a year of rule, the internecine rivalry between Egypt’s leading families struck again. This time, it was Hagar’s turn to be deposed, when a competitor usurped both the throne and the monuments of the fledgling dynasty.

As the merry-go-round of pharaonic politics continued to spin, it was only another twelve months before Hagar won back his throne, proudly proclaiming that he was “repeating [his] appearance” as king. But it was a hollow boast. The monarchy had sunk to an all-time low. Devoid of respect and stripped of mystique, it was but a pale imitation of past pharaonic glories. Hagar managed to cling to power for another decade, but his ineffectual son (a second Nayfaurud) lasted barely sixteen weeks. In October 380, an army general from Tjebnetjer seized the throne. He represented the third delta family to rule Egypt in just two decades.

However, Nakhtnebef (380–362) was a man in a different mold from his immediate predecessors. He had witnessed firsthand the recent bitter struggle between competing warlords, including “the disaster of the king who came before,” and understood better than most the throne’s vulnerability. As an army man, he knew that military might was a prerequisite for political power. Therefore, his number one priority, with the country living under the constant threat of Persian invasion, was to be a “mighty king who guards Egypt, a copper wall that protects Egypt.” But he also appreciated that force alone was not sufficient. Egyptian kingship had always worked best on a psychological level. Not for nothing did Nakhtnebef describe himself as a ruler “who cuts out the hearts of the treason-hearted.” If the monarchy were to be restored to a position of respect, it would need to project a traditional, uncompromising image to the country at large. So, hand in hand with the usual political maneuvering (such as assigning all the most influential positions in government to his relatives and trusted supporters), Nakhtnebef embarked upon the most ambitious temple building program the country had seen for eight hundred years. He wanted to demonstrate unequivocally that he was a pharaoh in the traditional mold. In the same vein, one of his very first acts as king was to assign one-tenth of the royal revenues collected at Naukratis—from customs dues on riverine imports and taxes levied on locally manufactured goods—to the temple of Neith at Sais. That achieved the twin aims of placating his Saite rivals while promoting his own credentials as a pious king. Further endowments followed, not least to the temple of Horus at Edfu. Nothing could be more appropriate than for the god’s earthly incarnation to give generously to his patron’s principal cult center.

Nakhtnebef was not simply interested in buying credit in heaven. He also recognized that the temples controlled much of the country’s temporal wealth, agricultural land, mining rights, craft workshops, and trading agreements, and that investing in them was the surest way to boost the national economy. This, in turn, was the quickest and most effective method of generating surplus revenue with which to strengthen Egypt’s defensive capability, in the form of hired Greek mercenaries. So placating the gods and building up the army were two sides of the same coin. Yet it was a tricky balancing act. Milk the temples too eagerly, and they might come to resent being used as cash cows.

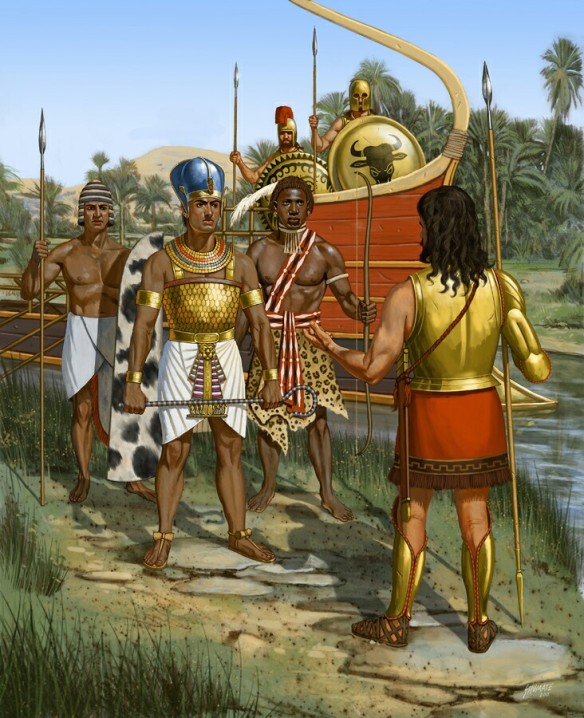

A wise student of his country’s history, Nakhtnebef moved to avoid the dynastic strife of recent decades by resuscitating the ancient practice of co-regency, appointing his heir Djedher (365–360) as joint sovereign to ensure a smooth transition of power. However, the greatest threat to Djedher’s throne came not from internal rivals but from his own cavalier domestic and foreign policies. Sharing none of his father’s caution, he began his sole reign by setting out to seize Palestine and Phoenicia from the Persians. Perhaps he wished to recapture the glories of Egypt’s imperial past, or perhaps he felt the need to take the war to the enemy to justify his dynasty’s continued grip on power. Either way, it was a rash and foolish decision. Even though Persia was distracted by a satraps revolt in Asia Minor, it could hardly be expected to contemplate the loss of its Near Eastern possessions with equanimity. Moreover, the vast resources needed by Egypt to undertake a major military campaign risked putting an unbearable strain on the country’s still fragile economy. Djedher badly needed bullion to hire Greek mercenaries, and was persuaded that a windfall tax on the temples was the easiest way of filling the government’s coffers. Hence, alongside a tax on buildings, a poll tax, a purchase tax on commodities, and extra dues on shipping, Djedher moved to sequestrate temple property. It would have been difficult to conceive of a more unpopular set of policies. To make matters worse, the Spartan mercenaries hired with all this tax revenue—a thousand hoplite troops and thirty military advisers—came with their own officer, Egypt’s old ally Agesilaos. At the age of eighty-four, he was a veteran in every sense of the word, and he was not about to be palmed off with the command of a mercenary corps. Only command of the entire army would satisfy him. For Djedher, that meant shunting aside another Greek ally, the Athenian Chabrias, who had first been hired by Hagar in the 380s to oversee Egyptian defense policy. With Chabrias placed in charge of the navy, Agesilaos won control of the land forces. But the presence of three such large egos at the top of the chain of command threatened to destabilize the entire operation. With resentment in the country at large over the punitive taxes, an atmosphere of suspicion and paranoia pervaded the expedition from the outset.

The most vivid account of events surrounding Djedher’s ill-fated campaign of 360 is provided by an eyewitness, a snake doctor from the central delta by the name of Wennefer. Born fewer than ten miles from the dynastic capital of Tjebnetjer, Wennefer was just the sort of faithful follower favored by Nakhtnebef and his regime. After early training in the local temple, Wennefer specialized in medicine and magic, and it was in this context that he came to Djedher’s attention. When the king decided to launch his campaign against Persia, Wennefer was entrusted with keeping the official war diary. Words had great magical potency in ancient Egypt, so this was a highly sensitive role for which an accomplished magician and archloyalist was the obvious choice. Yet no sooner had Wennefer set out with the king and the army on their march into Asia than a letter was delivered to the regent in Memphis implicating Wennefer in a plot. He was arrested, bound in copper chains, and taken back to Egypt to be interrogated in the regent’s presence. Like any successful official in fourth-century Egypt, Wennefer was adept at extricating himself from compromising situations. Through some astute maneuvering, he emerged from his ordeal as a loyal confidant of the regent. He was given official protection and showered with gifts.

In the meantime, before a shot had been fired, most of the army had begun to desert Djedher in favor of one of his young officers—no less a personage than Prince Nakhthorheb, Djedher’s own nephew and the Memphis regent’s son. Agesilaos the Spartan reveled in his role as kingmaker and threw his lot in with the prince, accompanying him back to Egypt in triumph, fighting off a challenger, and finally seeing him installed as pharaoh. For his pains, he received the princely sum of 230 silver talents—enough to bankroll five thousand mercenaries for a year—and headed home to Sparta.

By contrast, Djedher, disgraced, deserted, and deposed, took the only option available and fled into the arms of the Persians, the very enemy he had been preparing to fight. Wennefer was promptly dispatched at the head of a naval task force to comb Asia and track down the traitor. Djedher was eventually located in Susa, and the Persians were only too glad to rid themselves of their unwelcome guest. Wennefer brought him home in chains, and was showered with gifts by a grateful king. In a time of political instability, it paid to be on the winning side.