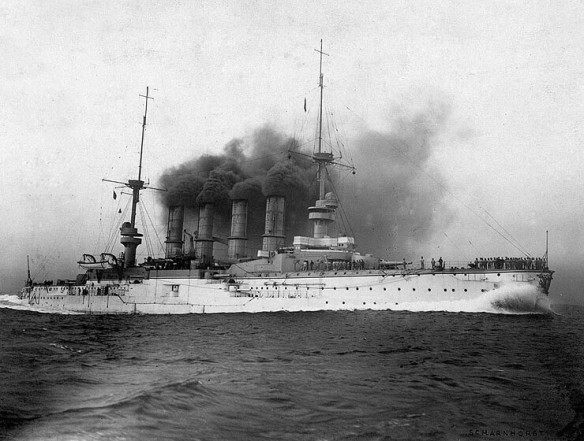

SMS Scharnhorst at sea.

Admiral von Spee’s squadron in line ahead off Chile in late November 1914: SMS Scharnhorst (the most distant ship), SMS Gneisenau, SMS Leipzig, SMS Nürnberg and SMS Dresden (in the foreground)

German armoured cruiser class, built 1904- 08. Two large cruisers, D and C, were authorized in 1904; they were launched respectively as Scharnhorst by Blohm und Voss on March 22, 1906, and Gneisenau by AG Weser on June 14 the same year. They were the last classic armoured cruisers built for the German navy.

In every respect they were a great improvement over previous German cruisers ¬and compared well with foreign contemporaries. However, the British ‘Dreadnought’ armoured cruisers of the Invincible Class rendered them obsolete by the time they were completed.

Upon completion, both ships were sent to the German colony of Tsingtau in China. In 1914 the Scharnhorst served as flagship for Commander of the East Asiatic Squadron Vice Admiral Maximilian Reichsgraf von Spee. Charged with protecting German territory in the Pacific, the squadron was regarded as the most efficient and effective in the Imperial German Navy, with long-service officers and sailors. When war began in August 1914, Spee sailed with his command from Ponape Island to avoid certain destruction by superior British and Japanese forces. He attacked Allied shipping while sailing eastward toward South America, determined to return the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau to Germany by way of Cape Horn.

On 1 November 1914, Spee’s squadron encountered an inferior British squadron under Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock off the Chilean port of Coronel. The Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau quickly sank two armored cruisers in a stunning embarrassment for the Royal Navy. London dispatched additional ships to intercept Spee, including the new battle cruisers Invincible and Inflexible. On 8 December 1914, this force under Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee pursued Spee’s squadron off the Falkland Islands and sank both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in a four-hour battle.

Battle of Coronel, (1 November 1914)

Key early World War I naval battle between the Royal Navy and the German East Asia Squadron. With the outbreak of war in August 1914, German Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee moved his East Asia Squadron of the armored cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the light cruisers Nürnberg, Dresden, and Leipzig from Tsingtao to Easter Island. There he learned that British Vice Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock’s flagship Good Hope, another armored cruiser, the Monmouth, and the light cruiser Glasgow were nearby.

The Royal Navy was aware of Spee’s presence in the area. Cradock feared that the Germans would attack the Falkland Islands, the English Bank, and the Abrolhos coaling bases, and he telegraphed London requesting that strong Royal Navy units be positioned on both coasts of South America.

The Admiralty denied the request. Instead, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill ordered out the old battleship Canopus, armed with 4 × 12-inch guns, despite Cradock’s protest that she would slow his squadron’s speed to only 12 knots. It was unclear how Cradock would be able to engage and defeat Spee’s squadron, which was capable of 20 knots. Besides, the battleship’s guns were of an early type that could not outrange Spee’s smaller guns, and her gun crews were reservists who had not had an opportunity to practice firing. The Canopus arrived at the Falklands on 22 October and underwent maintenance there to improve her speed.

Cradock, meanwhile, left the Canopus at Port Stanley and began a search for what he assumed to be a single German ship, the Leipzig. At the same time, the Germans were hunting the Glasgow, which Cradock had detached to Coronel on 27 October under orders that she rendezvous with the rest of the squadron on 1 November. This situation, where each side was searching for a single enemy ship, brought the two enemy squadrons together off the west coast of South America, near Coronel.

At 4:40 p.m. on November 1 during his northward search for the Leipzig, Cradock’s ships sighted the German cruiser squadron. Although the two squadrons were approximately equal in total firepower, the Germans held a clear advantage. The Good Hope had 2 × 9.2-inch guns at bow and stern, and 16 × 6-inch guns; it was the only ship in the squadron with guns of that size. None of the other ships in Cradock’s squadron had guns larger than 6 inches; without the Canopus, Cradock was at a grave disadvantage.

The German force, on the other hand, had more long-range guns. The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau each mounted 8 × 8.2-inch guns with a maximum range of 13,500 meters. These were the weapons that would decide the outcome of the battle. At 6:34 p.m. the Germans opened the action at 12,300 meters, barely within the 12,500-meter range of Cradock’s largest guns. Within minutes the Otranto sheered out of action; at 6:50 the Monmouth fell out of line, damaged and helpless, and 33 minutes later the Germans hit the Good Hope, which exploded. At 7:26 the German cruisers ceased fire. The Good Hope sank at about 10:00 p.m., with her total complement of 900 aboard, including Cradock.

Of the three ships in the British squadron, the Monmouth drifted until about 12:00, when the Nürnberg located and sank her in the darkness. Her total complement of 675 men was lost. Only the Glasgow and Otranto were able to escape into the night.

The Battle of Coronel was a demoralizing setback for the Admiralty and the entire British nation. The loss of two elderly cruisers could hardly affect the naval balance, but the news shocked Britain, as the public had not expected a defeat of this magnitude. German losses were trifling. More serious was the expenditure of 42 percent of the squadron’s 8.2-inch ammunition, which could not be replaced from Germany.

There was some fear in London that Spee would steam around Cape Horn and attack the vulnerable British naval installations. A month later, however, Vice Admiral F. D. Sturdee’s battle cruisers caught and defeated Spee’s squadron in the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Battle of the Falklands, (8 December 1914)

World War I naval battle. Following his victory in the Battle of Coronel on 1 November 1914, Vice Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee, commanding the German East Asia Squadron, decided to leave the southeast Pacific Ocean. Spee planned to move his squadron—consisting of the armored cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and light cruisers Dresden, Leipzig, and Nürnberg—into the southwest Atlantic Ocean to meet a supply ship. After arriving in the Strait of Magellan, Spee decided to attack the Falkland Islands, burn coal stored there, and destroy the wireless station.

Meanwhile, in response to the humiliating loss at Coronel, the British Admiralty sent out additional naval assets to Port Stanley in the Falklands. Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Doveton Sturdee’s force arrived at Port Stanley on 7 December 1914. He had the modern battle cruisers Invincible and Inflexible, along with the cruisers Carnarvon, Bristol, Kent, Glasgow, and Cornwall, and the auxiliary cruiser Macedonia. The old battleship Canopus was positioned on a mud flat near the harbor’s entrance to serve as a stationary fortress.

As his ships approached the Falkland Islands early on 8 December, Spee detached the Gneisenau and Nürnberg to conduct the raid. His remaining ships would search for British warships. At about 8:30 a.m. Sturdee received word of the German approach.

At Port Stanley some of the cruisers were undergoing repairs, and others were coaling. The smoke from ships trying to raise steam caught the attention of the captain of the Gneisenau as the German raiders neared the harbor mouth. Frantically, the German ships turned away as salvoes from the Canopus splashed near them. Sturdee set out in pursuit at 9:45 a.m., leaving the Kent and the Macedonia behind.

The Invincible and Inflexible were faster than the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and soon overtook them. Reversing the circumstances of Coronel, the British had the advantage in heavier, longer range guns (12-inch on the battle cruisers versus 8.2-inch on the German armored cruisers). Sturdee used this to his advantage, fighting a long-range battle that the Germans could not win.

Sturdee opened fire on the trailing German cruisers just before 1:00 p.m., whereupon Spee ordered his light cruisers to disperse and attempt to escape. Sturdee sent his own cruisers in pursuit of them, while his battle cruisers chased down the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The Scharnhorst was first to sink; the Gneisenau, crippled, was scuttled.

In the battle between the German light cruisers and the heavier British cruisers, only the Dresden escaped. She remained at large for over three months before being scuttled off Chile on 14 March 1915. Sturdee’s force suffered only 6 killed and 15 wounded. Only 157 Germans survived from the ships that had been sunk; some 2,000 were lost.

The Battle of the Falklands ended the one major surface threat to the Royal Navy that was outside the North Sea.

Specifications

Displacement: 11,616 tons (normal), 12985 tons (full load)

Length: 144.6 m (474 ft 5 in) oa

Beam: 21.6 m (70 ft 11 in)

Draught: 8.37 m (27 ft 6 in) max

Machinery: 3-shaft reciprocating steam, 26000 ihp=22.5 knots

Armament: 8 21-cm (8.2- in) L/40 (2×2, 4×1); 6 15-cm (5.9-in) L/40 (6×1); 18 8.8-cm (3.46-in) L/35 (18×1); 4 45-cm (17.7- in) torpedo tubes (submerged; 1 bow, 1 stern, 2 beam)

Crew: 764 (840 as flagship)