It was in 525 BC that the Persian Emperor Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, made the decision to invade Egypt and his armies successfully overthrew the native Egyptian pharaoh, Psamtek III, who was to become the last ruler of Egypt’s 26th Dynasty.

The Persian conqueror became the first ruler of Egypt’s 27th Persian Dynasty. Cambyses’ father had earlier attempted an invasion of Egypt against Psamtek III’s predecessor, Amasis, but Cyrus’ death in 529 BC put a halt to that expedition.

After capturing Egypt, Cambyses took the Throne name Mesut-i-re (Mesuti-Ra), which means ‘Offspring of Re’ and the Persians would go on to rule Egypt for the next 193 years until the day when Alexander the Great would defeat Darius III and himself conquer Egypt in 332 BC.

Little is known about Cambyses II through fashionable texts, but his reputation as a mad tyrannical despot has been recorded in the writings of the great Greek historian Herodotus around 440 BC. There is also a Jewish document from 407 BC known as ‘The Demotic Chronicle’ which speaks of the Persian king destroying all the temples of the Egyptian gods.

Now what is truth and what is fiction regarding his ‘nature’ is also an interesting case to be heard, and when you remember that the Greek’s held no love for the Persians the stories may well have been embellished. Herodotus informs us that Cambyses II was a monster of cruelty and impiety.

Herodotus tells us that the Persians easily entered Egypt across the desert and this invasion was aided by the defecting mercenary general, Phanes of Halicarnassus, who employed the Bedouins as guides. However, Phanes had left his two sons in Egypt.

Myth has it that by way of teaching Phanes a lesson for his treachery, as the two great armies lined up for battle his sons were bought out in front of the Egyptian army where they could be seen by their father, and their throats were slit over a large bowl. Herodotus also tells us that water and wine were added to the contents of the bowl and drunk by every Egyptian man.

The ensuing Battle at Pelusium began, Greek Pelos, which was the gateway to Egypt. Its location on Egypt’s eastern boundary made it an important trading post and therefore made it of immense strategic importance. It was the starting point for Egyptian expeditions to Asia and an entry point for invaders.

At this battle the Egyptian forces were crushed in the battle and they fled back to Memphis. Psamtek III managed to escape the ensuing besiege of the Egyptian capital, only to be captured shortly afterwards and was carried off to Susa in chains.

In the next three years of his rule over Egypt it has to be wondered how Cambyses II managed to pull of the victory at Pelusium. He personally went on to lead a disastrous campaign up the River Nile into Ethiopia. Here we learn that so ill-prepared was his mercenary army that when the meagerly supplied food ran out they were forced to eat the flesh of their own colleagues under the blazing sun of the Nubian Desert. The Persian army returned northwards in abject humiliation having failed to even encounter their enemy in battle.

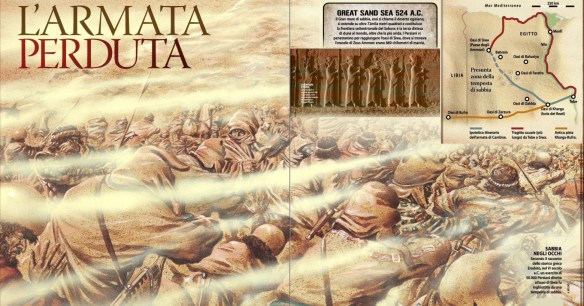

But perhaps more incredible is the saga of the missing army of 50,000 men. Here we have a pretty huge force heading into the Western Desert on their way to the Siwa Oasis, hell bent on destroying it. It left from ancient Thebes (modern Luxor) to attack the Oracle at Siwa Oasis but it never got there.

Herodotus said a sandstorm overwhelmed this army leaving historians to look for it ever since and even modern technology has failed to find it. The army just vanished along with all of its weapons and other equipment, never to be heard of again.

Cambyses II had also planned a military campaign against Carthage, but this was to be aborted because his Phoenician sea captains refused to attack their kinfolk who had founded the Carthaginian colony towards the end of the 8th century BC.

#

The Archaeological Proof?

A 5,000-10,000 [Note: probably its true strength] man Persian Army, a lost army swallowed in a sandstorm in 524 B.C., according to the account of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

The 2014 excavations of New York University at Amheida, Dakhla Oasis, Egypt, uncovered evidence for a temple building, or part of a temple building, erected in the name of the king Petubastis III. This building sheds more light on the Persian occupation of Egypt, and on the army sent by Cambyses into the Egyptian Western Desert. Olaf Kaper of Leiden University presented this discovery at an international congress on ‘Political Memory in and after the Persian Empire’, held at Leiden June 18-20 (see further: Leiden University Press Release).

In May 525 BC Cambyses captured Egypt, and his reign is counted as the start of the 27th Dynasty, while Egypt was part of the Persian empire. There was much resistance against this foreign occupation. The last king of the previous dynasty, Psamtek III, organized a revolt in 524, which ended in his assassination.

Between 522 and 520 there was a second large rebellion led by a local ruler named Petubastis III, who declared himself king of Egypt. This rebellion was until now known only from a few written sources from the region south of Memphis, but the new evidence shows that this ruler claimed full royal titles and that he was especially active in the southern oases.

Petubastis III built a temple building for the god Thoth at Amheida, the only temple known to have been built by this king. It indicates that he had a powerbase in the Western Desert, and perhaps specifically at Dakhla. His revolt may have started in the oases and spread to the Nile delta, from where the Persians ruled Egypt.

The presence of this king in the oases must have been the reason why Cambyses sent an army into the Western Desert, which never returned. Herodotus says that the army disappeared in a desert storm, but the new evidence suggests that this army may have been sent out against the army of Petubastis III, and that it perhaps suffered a humiliating defeat.

Excavations by New York University at the site of Amheida are directed by Roger Bagnall; Paola Davoli (University of Salento) is the archaeological field director, and Olaf Kaper is the associate director for Egyptology.