Arguably the best-known fighter in the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) in the first year of direct American participation in the war was the Curtiss P-40. Designed by Donovan Reese Berlin, the prototype XP-40 was more evolutionary than revolutionary in conception, being nothing more than the tenth production airframe of Berlin’s P-36A Hawk fighter with an Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled inline engine substituted for the P-36’s 875-horsepower Wright GR-1820-G3 Cyclone air-cooled radial.

Donovan’s original monoplane design dated to 1934. He designated it the Curtiss Model 75, reflecting his obsession with that number, while the emotive nickname of “Hawk,” already famous from an earlier generation of Curtiss biplane fighters, was revived for the new-generation monoplane. Although the Hawk 75 first flew in 1935, engine problems delayed its development until July 7, 1937, when the Army Air Corps gave Curtiss the largest American peacetime production order up to that time—210 P-36s, as the Army called them, for $4,113,550. Hawk 75s—built with retractable landing gear or with fixed, spatted undercarriage, depending on whether speed or simplicity was the customer’s main priority—were also sold to numerous foreign air arms.

The first to employ them in combat were the Chinese. The first Hawk 75 to arrive was purchased by Madame Chiang Kai-shek for $35,000 as a present for Col. Claire Lee Chennault in July 1937. In July 1938, the first official Chinese air force consignment of Hawk 75Ms with fixed undercarriage was assigned to the veteran 25th Pursuit Squadron, whose pilots began training under Chennault’s tutelage. Its baptism of fire came on August 18, when twenty-seven Mitsubishi G3M2s came in three waves to bomb Hengyang, and Squadron Commander Tang Pusheng led three of the new Hawks up along with seven I-152s. Intercepting the first flight of nine, Tang shot one down and damaged another, then attacked the second wave of bombers, only to be caught in a cross fire from the gunners, who shot him down in flames. The two other Hawk 75Ms crashed on landing.

On October 1, nine more Hawk 75Ms were assigned to the 16th Pursuit Squadron at Zhiguang, which had just been redesignated from a light bomber unit that had previously flown Vought V-92 Corsairs. Similarly, the next unit to get nine Hawk 75Ms, the 18th Pursuit Squadron, had previously flown Douglas O-1MCs. Training continued apace but suffered a setback on January 2, 1939, when five pilots of the 25th Squadron were killed in crashes while flying from Kunming to Sichuan. Curtiss Hawk III biplanes were assigned to the squadron to supplement its reduced numbers. Chinese confidence in the new plane remained so low three months later that when twenty-three Japanese bombers raided Kunming on April 8, no Hawks rose to challenge them, and the nine were bombed to destruction on the ground.

In August 1939 the 25th Squadron was disbanded, followed by the 16th within the following month, leaving only the 18th to be attached to the newly formed 11th Pursuit Group, which operated six Hawk 75Ms alongside I-152s and I-16s. Success continued to elude the monoplane Hawks, and the ultimate blow came on October 4, 1940, when twenty-seven G4Ms attacked Chengdu, escorted by eight new A6M2 Zeros of the 12th Kokutai, led by Lt. Tamotsu Yokoyama and Lt. j.g. Ayao Shirane. Far from intercepting the enemy, the 18th Pursuit Squadron was ordered by the Third Army air staff to disperse to Guangxi, but as it did some of its planes were caught en route by the aggressive Zeros. Hawk 75M No. 5044 was shot down in flames and its pilot, Shi Ganzhen, killed when his parachute failed to open. Additionally, an I-152 and a Gladiator were sent crashing with their respective pilots, Gin Wei and Liu Jon, wounded. Two other I-152s returning to base with engine trouble, piloted by Zing Ziaoxi and Liang Zhengsheng, were strafed as they landed and were apparently counted among the five “I-16s” the Zero pilots claimed to have shot down, along with an “SB-2 bomber,” which was in fact an Ilyushin DB-3 of the 6th Bomber Squadron, returning on the mistaken assumption that the raid was over, only to be destroyed with its three crewmen.

At Taipingzhi airfield the Japanese reported destroying nineteen aircraft on the ground, four of their pilots audaciously landing to set fire to some of them. The Chinese acknowledged the loss of two I-16s, two I-152s, two Hawk IIIs, six Fleet trainers, one Beech UC-43 Traveler, a Dewoitine 510, and a Hawk 75M. The Hawk 75M’s inauspicious combat debut in China officially came to an end when the virtually impotent 18th Pursuit Group was disbanded in January 1941.

Although its performance was eclipsed by other types by 1940, the Hawk 75 was fondly remembered by a lot of others who flew it for its easy handling and excellent maneuverability. Export Hawk 75As, powered by 950-horsepower Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp engines, became the best fighters available in quantity to the French in May 1940, and were credited with more enemy planes shot down than any other French fighter. Thailand purchased Hawk 75Ns with fixed landing gear and used them during its war against the French in Indochina in January 1941, as well as during its brief resistance to invading Japanese forces that December. The US Army Air Corps still had P-36Cs on strength when Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, and they scored some of the first American air-to-air victories that day. The exiled Royal Netherlands Air Force used Cyclone-engine P-36s in the East Indies, where they became easy prey for the Japanese Zero. The RAF also used P-36s, which it called Mohawks, as stopgap fighters, most notably in Burma in 1942. Vichy French pilots flew Hawk 75As against the British and Americans during their invasion of North Africa in November 1942, and other French H-75As, shipped to Finland by the Germans, fought the Soviets until September 1944. Although neither as modern nor as famous as the P-40 that succeeded it, the P-36 can lay claim to greater ubiquity and the rare—if somewhat dubious—distinction of having fought on both sides during World War II.

The Allison-engine XP-40 first flew on October 14, 1938, and competed against the Lockheed XP-38, Bell XP-39, and Seversky AP-4 at Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio, on January 25, 1939. The XP-40 emerged the winner, and in April Curtiss was rewarded with what was touted as the largest contract since World War I, for 543 P-40s.

Although outclassed by the Zero, P-40s soldiered on as best they could, starting with the very first Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In the months that followed, the P-40 pilots fought desperately and often heroically, with decidedly mixed fortunes. They were ultimately annihilated in the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies, but in the hands of master tactician Col. Claire Chennault and his American Volunteer Group in China, the Hawk 81 (as the export version of the P-40 was known) did a disproportionate amount of damage and became one of the war’s legendary fighters.

More than half a year before the United States entered the war, however, P-40s had already fought over terrain that could not have been farther removed from Pearl Harbor, the mountains of China, or the jungles of Southeast Asia.

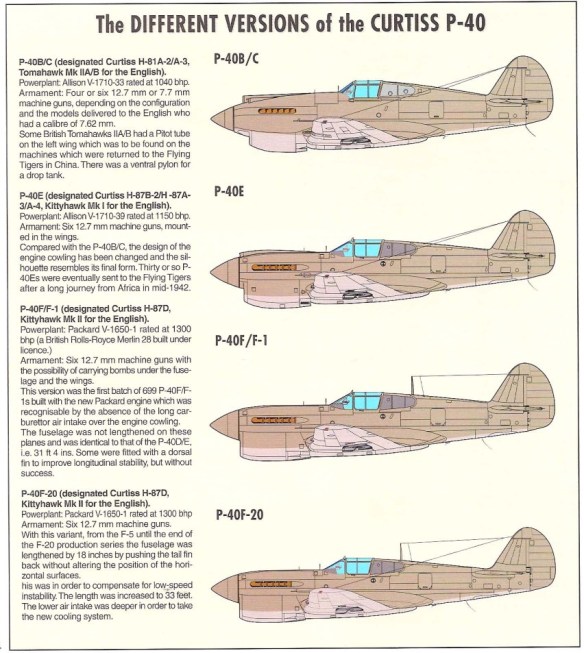

Even while it was filling the Army Air Corps orders for P-36s and P-40s, Curtiss was marketing both the Hawk 75 and 81 to overseas customers. Although not used quite as widely as the Hawk 75, the Hawk 81 saw considerable Chinese use—first by the American mercenaries of the AVG and later by Chinese pilots—as well as service in the Soviet army and naval air arms, the RAF, and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). It was, in fact, in British service that the “Hawk” designator probably got more use in reference to the P-40 than it ever did by the fighter’s American pilots. The earliest models were called Tomahawks by the British, while the later ones were christened Kittyhawks.

The first major action in which Tomahawks figured prominently was a sideshow that nevertheless serves as a reminder of just how global a conflict World War II was. On May 2, 1941, British forces in Iraq came under attack by Iraqi forces directed by the anti-British, pro-German chief of the National Defense Government, Rashid Ali El Ghailani. The revolt was quickly crushed and Rashid Ali fled the country on May 30, but not before a number of Axis aircraft had been committed to his cause. Sixty-two German transport aircraft carried matériel to the Iraqis, making refueling stops at airfields in Syria and Lebanon, then mandates of nominally neutral Vichy France. The Germans and Italians had also sent fighters and bombers which, hastily adorned in Iraqi markings, had made their way into the country from the French air bases. Amid the British counterattack, at 1650 hours on May 14, two Tomahawk Mark IIbs of No. 250 Squadron RAF, flown by Flying Officers Gordon A. Wolsey and Frederick J. S. Aldridge, carried out the first P-40 combat mission when they escorted three Bristol Blenheims in an attack on suspected German and Italian aircraft at Palmyra in Syria.

In allowing Axis planes to stage from their territory, the French-mandated Levant presented a threat to British security in Palestine and Egypt at a time when Generalleutnant (Major General) Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps was starting to make its presence felt in North Africa. On May 15, British aircraft attacked French air bases at Palmyra, Rayack, Damascus, Homs, Tripoli, and Beirut. The Vichy government responded by dispatching Groupe de Chasse III/6 to Rayak, with a complement of top-of-the-line Dewoitine D.520 fighters. In addition to those, Général de Division (Major General) Jean-François Jannekeyn, commander of the Armée de l’Air in the Levant, had GC I/7, equipped with Morane-Saulnier MS.406 fighters; Groupe de Bombardment II/39, with American-built Glenn Martin 167F twin-engine bombers; GB III/39, with antiquated Bloch 200s; Groupe de Reconnaissance (GR) II/39 and Flight GAO 583, both with Potez 63-IIs; and a myriad of less effective army and navy planes at his disposal for a total of ninety aircraft.

By the end of May, the British had decided to seize the Levant. General Archibald Wavell organized an invasion force by pulling the Australian 7th Division, less one brigade, from its defensive position at Mersa Matruh and combined it with the 5th Brigade of the Indian 4th Division, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division, a commando unit from Cyprus, a squadron of armored cars, and a cavalry regiment. The scratch force was to receive some offshore support from the Royal Navy, and air support from sixty aircraft of the RAF and the RAAF. The Aussie contingent included Tomahawk Mark IIbs newly delivered to replace the Gladiators of No. 3 Squadron RAAF at Lydda, Palestine. Meanwhile, on May 22, No. 250 Squadron had been reassigned to the defense of Alexandria, Egypt.

The three-pronged invasion, dubbed Operation Exporter, commenced from Palestine and Trans-Jordan at 0200 hours on June 8. The British and accompanying Gaullist French forces had hoped that the 35,000 Vichy troops in Syria would be loath to fight their former allies, but they were in for a disappointment. Anticipating Allied propaganda appeals based on the idea of saving Syria from German domination, Vichy High Commissioner Gen. Henri-Fernand Dentz saw to it that all signs of German presence were removed throughout the country. The Luftwaffe, too, had discretely evacuated all of its planes, aircrews, and technicians from the Syrian airfields forty-eight hours ahead of the expected invasion. In consequence the Allied propaganda fell on deaf ears, the French officers defending Syria refused to deal with their Gaullist compatriots, and the Allied invasion force found itself with a fight on its hands.

On the day of the invasion, June 8, Hurricanes of Nos. 80, 108, and 260 Squadrons, and five Tomahawks of No. 3 Squadron, RAAF, made preemptive attacks on the French airfields. Among other targets, the Hurricanes and Tomahawks strafed GC III/6’s fighters on the ground at Rayak, burning a D.520 and damaging seven others. On this occasion, the Tomahawks drew relatively little fire from French ground gunners, who mistook the unfamiliar new fighters for their own D.520s. On the same day, two Tomahawks of 250 Squadron, flown by Flying Officer Jack Hamlyn and Flt. Sgt. Thomas G. Paxton, together with shore batteries, shot down an intruding Cant Z.1007bis reconnaissance bomber of the Italian 211a Squadriglia five miles northwest of Alexandria.

As Vichy France rushed reinforcements to the Levant, the Germans and Italians put airstrips in newly conquered Greece at their disposal, allowing the swift ferrying of Lioré et Olivier LéO 451 bombers of GB I/31, I/14, and I/25; D.520s of GC II/3; and Martin 167s of the 4e Flotille of the Aéronavale to Syria by June 17.

French bombers attacked Adm. Sir Andrew Cunningham’s naval force off Saida on June 9, damaging two ships. Eight German Junkers Ju 88A-5s of II Gruppe, Lehrgeschwader 1, operating from Crete, also turned up to harass the fleet on June 12, but they were intercepted by Tomahawks of No. 3 Squadron. Squadron Leader Peter Jeffrey shot down one of the attackers, Flt. Lts. John R. “Jock” Perrin and John H. Saunders claimed two others, while Flt. Lt. Robert H. Gibbes caught a fourth bomber right over the fleet and claimed it as a “probable.” In fact, two Ju 88s failed to return—one from the 4th Staffel, piloted by Ltn. Heinrich Diekjobst, and one from the 5th Staffel, flown by Ltn. Rolf Bennewitz.

Three days later, the Aussies turned their attention to the Vichy French, as Jeffrey and Flt. Lt. Peter St. George B. Turnbull each accounted for a Martin 167F of GB I/39 in the area of Sheik Meskine. On June 19, Turnbull damaged another Martin bomber over Saida, and Pilot Officer Alan C. Rawlinson damaged two others near Jezzine. Damascus fell to the Allied forces on June 21. In an encounter between Tomahawks and D.520s of GC III/6 two days later, Capitaine Léon Richard, commander of the 6e Escadrille, was credited with shooting down a Tomahawk south of Zahle—probably Turnbull, who crashed his damaged Tomahawk upon returning to Jenin. The starboard wing of Sgt. Frank B. Reid’s Tomahawk was also damaged by 20mm shells, but the French took the worst of the fight. Sous-Lieutenant Pierre Le Gloan was forced to beat a hasty retreat when his D.520 began to burn, probably after being hit by Flying Officer Percival Roy Bothwell, who also sent Lt. Marcel Steunou, a five-victory ace, down in flames near Zahle, and killed Sgt. Maurice Savinel between Ablah and Malakaa. Flying Officer Lindsey E. S. Knowles claimed to have shot the wingtip off another Dewoitine, which was credited to him as damaged.

Among the toughest Vichy strongpoints was Palmyra, a fortified air base surrounded by concrete pillboxes, antitank ditches, observation posts, and snipers’ nests. When Habforce, a composite invasion group drawn from British and Arab troops occupying Iraq, crossed the border and moved on Palmyra on June 20, it came under heavy and very effective bombing and strafing attacks by the base’s aircraft. Habforce’s advance ground to a halt for about a week. Then, on June 25, appeals for air support by Habforce’s commander, Maj. Gen. J. George W. Clark, were finally answered as Commonwealth aircraft arrived, including No. 3 Squadron’s Tomahawks. In an aerial engagement fifteen miles southwest of Palmyra, Saunders, Flying Officers John F. Jackson and Wallace E. Jewell, and Sgt. Alan C. Cameron each claimed a LéO 451 of GB I/12—though only three such bombers were in fact present, and all were lost along with the lives of five of their twelve crewmen. When six Martin 167s of Flotille 4F sallied out of Palmyra to attack Habforce again on June 28, they were intercepted by No. 3 Squadron’s Tomahawks, and six were promptly shot down in sight of the British ground troops, Rawlinson accounting for three of them, Turnbull downing one, and Sgt. Rex K. Wilson destroying another. The action heralded a pivotal turn in Habforce’s fortunes, the day’s only sour note being struck after the Tomahawks refueled and returned to Jenin, where Sergeant Randall’s plane suffered engine failure, and he was killed in the crash.

Ultimately, the Allied forces prevailed, launching their final thrust on Beirut on July 7. Amid fierce but hopeless resistance, High Commissioner Dentz passed a note to Cornelius Engert, the US consul general in Beirut, expressing his willingness to discuss surrender terms with the British, but absolutely not with the Gaullist French.

Negotiations dragged on for sixty hours, during which fighting continued, and the Tomahawks had one more occasion to test their mettle against the D.520 in the air. On July 10, seven Tomahawks of No. 3 Squadron RAAF went to cover twelve Bristol Blenheims of No. 45 Squadron, which were to bomb an ammunition dump near Hamana, south of Beirut. The Blenheims bombed the target, but the explosions drew the attention of five D.520s of Aéronavale Flight 1AC, which had transferred to Lebanon six days earlier and were escorting Martin bombers on a mission. Attacking from head on and below, the French quickly shot down three Blenheims, riddled a fourth so badly that it subsequently had to crash-land, and damaged six others.

Diving to the belated rescue, the Tomahawk pilots claimed all five of the Dewoitines—two by Turnbull, and one each by Jackson, Pilot Officer Eric Lane, and Sgt. Geoffrey E. Hiller. In actuality, only two French fighters were lost: Second Maître (Petty Officer Second Class) Pierre Ancion was mortally wounded, dying in Beirut hospital two days later, while Premier Maître (Petty Officer First Class) Paul Goffeny bailed out of his burning D.520 over the Bakaa Valley with slight wounds, subsequently claiming that his pursuer had crashed into a mountain while trying to follow his evasive maneuvers. The other three French pilots returned—Enseigne de Vaisseau de 1ère Classe (Lieutenant Junior Grade) Jacques du Merle being credited with two bombers, Premier Maître Jean Bénézet with another, and Lieutenant de Vaisseau (Lieutenant) Edouard Pirel sharing in the destruction of the fourth Blenheim with Goffeny, who was also credited (wrongly) with the “crashed” Tomahawk.

On the following day, Lt. René Lèté of GC II/3, lagging behind his formation due to engine trouble, spotted three Tomahawks and attacked, shooting down Flying Officer Frank Fischer. Lèté was one of only two Frenchmen to shoot down a Tomahawk during the campaign, but he had little time to exalt in the distinction, for moments later Gibbes and Jackson got on his tail and claimed to have sent him down in flames—Bobby Gibbes subsequently getting full credit for his first of an eventual ten victories by winning the coin toss. In fact, Lèté survived his crash landing—as did Fischer, who, after hiding from the French in an Arab village, rejoined 3 Squadron after hostilities ceased. The squadron lost one other Tomahawk to antiaircraft fire over Djebel Mazar that day, Flying Officer Lin Knowles crash-landing near Yafour, ten miles from Damascus.

At 1201 hours on July 12, a cease-fire finally went into effect, ending the thirty-four-day Syrian campaign. A formal armistice was signed at Saint-Jean-d’Acre on July 14—Bastille Day, ironically enough. The Tomahawks of No. 3 Squadron RAAF were transferred to the Western Desert, where their colleagues in RAF and South African air squadrons were already battling the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica. Among other early successes over the Western Desert, Pilot Officer Thomas G. Paxton of 250 Squadron, who had shared in the Cant Z.1007bis on June 8, added an Me 109E to his growing score south of Tobruk on June 26, while on June 30 one of Paxton’s squadron mates, Sgt. Robert J. C. Whittle, shared in the destruction of an Me 110, damaged an Me 109, and probably downed an Italian aircraft.

And so, the Curtiss P-40 had its baptism of fire in the Middle East. Although its principal virtue in 1941 was its ready availability, great things would be done in the P-40, and a series of improved models kept the Curtiss fighter in production for five years, a total of 13,737 being produced.