On the morning of August 1, 1943, Consolidated B-24 Liberators attached to the IX USAAF Bomber Command were winging their way over the Eastern Mediterranean Sea toward Romania. Their target was supremely important, so much so, its obliteration could drastically affect the entire course of the European War. Ploiesti was the enemy’s chief source of petroleum, averaging 450,000 tons per month. If production could be curtailed, the Wehrmacht on every front must grind to a halt.

The Romanian oilfields had been struck once before, almost a year to the day earlier, when a dozen Liberators flying from Fayid, Egypt, staged a dawn raid that caused negligible damage, but the Americans suffered no casualties. Ground fire had been weak, and no defending aircraft were encountered, leading Allied strategists to conclude that Axis personnel and equipment were almost entirely engaged in fighting on the Eastern Front. German forces at the time were embroiled in the gigantic and distant Battle of Kursk, so no serious opposition was anticipated. Sufficient numbers of heavy-bombers were not available for follow-up raids on Ploiesti until after the close of the North African Campaign in May 1943, when planning for Operation Tidal Wave could begin. It called for a sustained aerial offensive that must level the Romanian city before the Luftwaffe could recall enough of its fighters from Russia to put up an adequate defense. The Romanians themselves were dismissed as an insignificant, pre-industrial people incapable of offering real resistance.

Liberators of August 1943 approached the Romanian border with Bulgaria, drawing close to combine their firepower and dropped down into a low-level attack mode for maximum accuracy. Ploiesti had no sooner come into view, however, when the most ferocious ground fire they ever encountered erupted within their formation. Before they reached the target area, 15 bombers had been shot down in rapid succession, and many others were damaged, some too seriously to proceed.

As the remaining B-24s initiated their bomb run, they were beset by Messerschmitt-109G fighters of the I./JG 4 and twin-engine Bf 110s interceptors from a Romanian night-fighter squadron. Joining the fray was an aircraft new to the Americans, and some of them guessed it was a variant of the Luftwaffe’s Focke-Wulf-190. It was not a German fighter, however, but the Romanian-designed and manufactured Industria Aeronautica Romana 81, or IAR 81, the foremost bomber-killer of the Fortelor Regal ale Aeriene Romana (FRAR), the Romanian Air Force. Although not particularly fast at 317 mph, the IAR 81 could climb to 16,400 feet in just six minutes and was exceptionally maneuverable at low altitudes.

The IAR 81s and Messerschmitts tore into the B-24s, throwing off their attack, which missed the crude oil pumping plants. Some refineries were damaged, but all of them were back operating at their former out-put shortly thereafter. During the engagement, the Romanians lost 2 planes but claimed 25 enemy aircraft destroyed. Of the 178 U.S. bombers that set out for the raid,1 crashed on takeoff, 15 lost their bearings en route to the target, 22 went astray or AWOL to land at neutral and other Allied airfields, and 51 were lost in combat. Just 89 Liberators returned to their base; 110 USAAF personnel had been captured by the enemy.

The Romanians’ vigorous defense of the skies over their homeland was rooted in a love of aviation that went back to the first years of the 20th century. Various flying clubs that sprouted throughout the country were often founded and led by cavalry officers, who eventually pooled their experience and resources to form the Fortelor Regal ale Aeriene Romana in 1913. During the years thereafter, three companies-the Societates Pentru Exploatari Technice, the Industria Aeronautica Romana, and Interprenderes de Constructii Aeronautice Romanesti-produced original designs and built foreign aircraft under license, a remarkable achievement for a predominantly agrarian nation.

The Romanian Air Force suddenly swelled with the addition of more than 250 Polish aircraft escaping from the German Blitzkrieg of September 1939. While most would serve as much-needed trainers and transports behind the lines, among them were about 60 fighters. These were examples of the PZL P.11, the world’s best fighter at the time it entered service during 1934. In the six years since then, it had been outclassed by the Messerschmit-109, but could still hold its own against many contemporary aircraft, and was superior to more than a few, thanks chiefly to its excellent handling capabilities and pilot visibility.

Romania was now a real air power in the Balkans, her squadrons a mix of indigenous aircraft and imports mostly from France and Poland, with fewer examples from Britain and Italy, as support for a strong army. These armed forces were unable, however, to deter Soviets annexation of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina on June 28, 1940. More Romanian lands were lost to Hungary and Bulgaria, further compromising national self-esteem. The crisis sparked by these seizures and the Kremlin’s intimidating posture brought about a fundamental change in the Bucharest government.

The former Minister of Defense, Marshal Ion Antonescu, was appointed Prime Minister by King Carol II, who was promptly deposed and replaced by Crown Prince Mihail, a virtual figurehead for the new dictatorship. In what Atonescu regarded as an inevitable confrontation between the USSR and Europe, he believed that alliance with the Third Reich would not only help end the growing Communist menace, but result in the return of his country’s territories parceled out to other countries by the framers of the Versailles Treaty after World War I, the despised Bulgarians and Hungarians, and Stalin. Accordingly, Romania joined the Tripartite Pact on November 23 and began building up her military strength.

Benefitting the FRAR were new arrivals from Germany. Heinkel’s 112 had lost out in Luftwaffe competition to the Messerschmitt-109, because the latter was faster, more reliable, and easier to mass produce. But the HE-112 was its superior in structural strength, handled better, and 30 specimens received by the Fortelor Regal ale Aeriene Romana joined its mixed company of British Hawker Hurricanes, Polish PZL high-wing fighters, Italian Fiat CR-42 biplanes, French Potez-63B2 light-bombers, and indigenous Romanian designs.

In mid-May 1941, these and all FRAR aircraft were painted with a new national insignia-a yellow cross outlined in blue and white with a blue dot at the center encircled by a red ring. This Maltese design was formed by a connected quartet of the letter “M;’ after the vainglorious but neither especially intelligent nor resolute King Mihail. Antonescu nonetheless tolerated him as a transitional figure to the folkish totalitarian society he envisioned for Romania. That goal seemed virtually achieved on September 14, 1940, when the new Prime Minister shared power with the Iron Guard in the creation of a National Legionary State. Founded 13 years earlier, the fascist Garda de Fier had become a powerful political phenomenon before the close of the 1930s. It was, however, made up of too many uncompromising hot-heads, whose disciplinary problems fatally sabotaged not only their own movement and Antonescu’s plans, but contributed to Romania’s ultimate betrayal by King Mihail, whose conspiratorial monarchy they inadvertently strengthened through their unruly behavior.

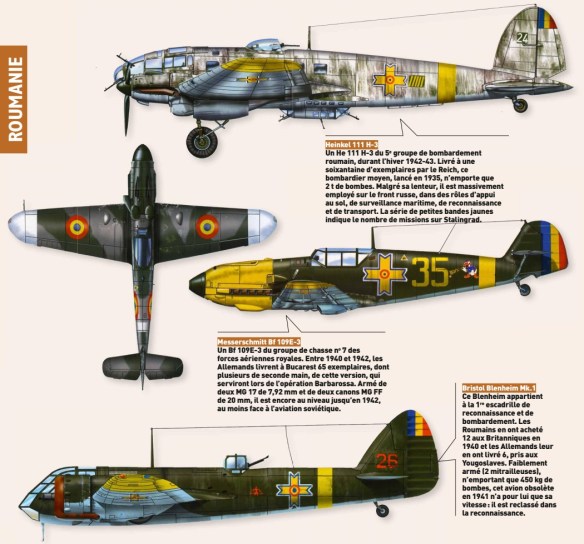

By the time Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, began on June 22, 1941, the FRAR fielded 253 warplanes in 17 fighter squadrons and 16 reconnaissance squadrons. Fourteen bomber squadrons were a mixed bag of patently outdated hand-me-downs from a dozen foreign air forces, plus 40, aging Junkers Ju.87B-2 Stuka dive-bombers received from Germany the year before. All Romanian aircraft participating in the Eastern Campaign belonged to the Gruparea Aeriana de Lupta, but those directly involved in combat operations were combined in their own unit as the Corpul Aerian Roman, the “Romanian Air Corps:” However, several dozen machines were either undergoing conversion or being repaired, allowing only 205 warplanes available for actual combat.

Like all Axis aircraft participating in the opening phase of Barbarossa, their engine cowlings were painted bright yellow. An identically colored band encircled the rear fuselage and covered the underside wing-tips for recognition purposes. One of these newly adorned warplanes was flown the second day of the Campaign by Lieutenant Agarici Horia in company with seven other Hawker Mk.1 Hurricanes of the 53rd Fighter Squadron patrolling the Black Sea port-city of Constanta. Sometime into the flight, oil spewed over his windscreen, and he returned to the airfield.

While mechanics attended to a ruptured gasket, air raid sirens announced the approach of Soviet bombers. Horia jumped back into the cockpit and cranked up the Hurricane’s unrepaired 1,030-hp Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. At 6,000 feet, he closed on the lead intruder, an Ilyushin DB-3. Squinting through the oil rising again over his windscreen, he surprised the medium-bomber to squeeze off an accurate fusillade from his eight, 303-inch Browning machine-guns on one of his target’s twin 950-hp Nazarov M-87 radial engines. It was abruptly consumed in fire, sending the Ilyushin out of control and into the sea.

Defensive fire from another DB-3’s trio of 7.62-mm ShKAS machineguns and 20-mm cannon could not save the Romanian lieutenant’s second victim from crash landing outside Constanta, where its crew was taken prisoner. The third bomber turned away and fled, but Horia took up the pursuit and shot it down in flames. Unnerved by these swift kills, Ilyushin pilots of another in-coming formation aborted their attack and circled back into the East. After Horia was able to land his oil-coated Hurricane, he was awarded the Virtutea Aerinautica Order Gold Cross. Before the year was out, he rose to the status of “ace” by destroying two more Soviet aircraft. He was flying an IAR-80 with the 58th Fighter Squadron on April 4, 1944, when he claimed a B-24 Liberator of the 15th Air Force, and went on to survive the war with 10 confirmed, plus 2 probable “kills:”

As early in the Campaign as was Horia’s success, it had been preceded several hours by Sit av Teodor Moscu in the Escaclrila 51 vdnatoare’s attack on Bulgarica airfield, in southern Bessarabia. His gray Heinkel-112 was jumped by five Polikarpov Ratas, three of which he shot down in such quick succession; the remaining two bolted from the scene. Soviet ack-ack offered fierce resistance, destroying 11 Romanian warplanes, 4 of them irreplaceable Bristol Blenheims. But the FRAR pilots, known as vknatori, got in the first strike, strafing 40 aircraft parked in the open at Bulgarica, and claiming another 8 in combat.

On July 12, the Red Army mounted a powerful counteroffensive to cut off Romanian forces battling for Bessarabia. As an immediate response, FRAR commanders ordered into the air 59 bombers-mostly Italian and Polish hand-me-downs-covered by 54 IAR-80s, Heinkel112s, Hawker Hurricanes, Fiat Falcons, and PZL P.11s. This mixed assortment armada swept the Soviets from the skies, then decimated enemy artillery, troops, transports, and tanks gathering in large numbers east of the Falciu bridgehead.

The bombing and strafing were unrelenting, and the desperation of the fighting was exemplified by the vknatori themselves. After expending all ammunition for his IAR-80’s twin 7.92-mm machine-guns in destroying three of the six Ratas attacking him, Sit av Vasile Claru rammed an 1-16 flown by Lieutenant Ilya M. Shamanov, a Soviet deputy squadron commander. Neither man survived the collision. On the ground, the Red Army counter-offensive had been reduced to a smoldering salvage dump.

By July 26, the FRAR established air supremacy over Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, having flown 5,100 missions at the cost of 58 aircraft shot down and 18 pilots killed. Against these losses, the vdnatori destroyed 88 enemy warplanes in aerial combat, together with another 108 on the ground, plus 59 brought down by flak. Romanian anti-aircraft gunners were among the deadliest of World War II, a reputation they would re-enforce later in defending the Ploiesti oil fields against USAAF raiders. Elsewhere, however, the Romanians were badly outnumbered in the air, as they would be for the rest of the war.

During an early morning patrol east of the Dnestr River on August 21, Sit av Micrea Dumitrescu was beset by eight Polikarpov I-16s. During the ensuing melee, his ex-Polish PZL fighter outmaneuvered the Soviet monoplanes to escape, but not without incurring significant damage.

Fresh from their victories in Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, Corpul Aerian Roman crews supported the Romanian 4th Army’s struggle for Odessa, the Black Sea’s primary harbor and communications facility. Stalin insisted that this vitally important center must not fall under any circumstances, but Axis commanders were no less determined to take it, as affirmed by the massive artillery barrage they hurled at the fortified city on August 8. The defenders continued to hold out for more than a month, waiting for a promised Soviet counter-offensive that would break the siege. It came during the night of September 21, when Red Army troops established a bridgehead at Chebanka-Grigorievka, from which they were about to attack the Romanian 4th Army’s weaker right flank.

Before they could move, 32 FRAR bombers escorted by 62 fighters, supplemented by another 23 Italian warplanes of the Regia Aeronautica, dove on the Soviet serpent as it was about to strike. A few Italian fighter pilots actually served with Romanian squadrons, such as Capitano Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli, Prince of Poggio Suasa, flying a Macchi C.200 Saetta “Thunderbolt” After 10 hours of nonstop bombing and strafing, the Red Army bridgehead was pulverized, and Stalin’s counteroffensive turned into a demoralized withdrawal. More than 20 Russian aircraft had been destroyed for the loss of a single FRAR fighter in aerial combat, plus four more to ground fire, which additionally claimed an Italian Savoia-Marchetti bomber. Odessa managed to hang on for another three weeks, but its capture on October 16 represented Romania’s greatest conquest of the war.

During these first few months of Operation Barbarossa, the FRAR’s most successful fighter squadron had been Escadrila 53 vdnatoare. Its pilots flew only Hawker Hurricanes, with which they accounted for nearly 100 enemy warplanes for the loss of just one comrade, five-kill ace, Cpt av loan Rosescu, before Odessa fell. Their prominence was something of an embarrassment to Hermann Goering, who learned that a British-built fighter had out-performed Germany’s own Heinkel112 in the hands of the Reich’s allies. Accordingly, he immediately donated specimens of the more up-to-date Messerschmitt-109E to FRAR squadrons, whose pilots were to prove that his Emil could indeed surpass the Hawker Hurricane in combat.

With the fall of Odessa, the vdnatori flew cover for the 3rd Army in its advance through Ukraine and then into the Crimea. They also operated the 101st and 102nd Seaplane Squadrons equipped, respectively, with 24 German Heinkel-114C1s and a dozen Italian CANT Seagulls for reconnaissance and anti-shipping duties over the Black Sea, with their main base at Mamaia. The Heinkel had been originally manufactured just prior to the outbreak of war specifically for the Kriegsmarine, performing spotter-plane duties aboard German warships. Armament consisted of a single, 7.92 mm MG 15 machine-gun on a flexible mount for the rearward observer, plus two, 110-pound bombs.

More important was the seaplane’s BMW 132K nine-cylinder radial engine, which delivered 960 hp for an operational range of 571 miles. The antiquated but sturdy aircraft carried out numerous reconnaissance flights, even attacks on Soviet shipping. Twenty one years after the type’s maiden flight in 1939, the last Heinkel-114 was retired from active duty with the Romanian Air Force, during May 1960. By early 1943, the doughty biplanes were being joined by another German contribution to FRAR operations over the Black Sea. With an effective range nearly 100 miles greater than the He-114, the better known and far superior Arado Ar. 196 began equipping the Romanian Escadrila 102 operating out of conquered Odessa.

Larger than the twin-float twin-place Arado was Italy’s CANT Z.501 flying boat. The aircraft’s prodigious range, together with its payload of 1,411 pounds of bombs, served Black Sea operations well. A turret mounted midway atop the 73-foot, 10-inch wing, while extremely unorthodox, afforded an almost unprecedented 365-degree field of fire for its 7.7-mm machine-gun. Outstanding was the sinking of two Soviet submarines by a single Gabbiano in August 1941, the surrender of an armed merchantman to a flight of Heinkels the following October, and effective cover provided to retreating Romanian forces during early summer 1944 by low-flying Arados. Other operations were less spectacular but quite useful. More often, the Romanian-crewed seaplanes were busy monitoring the whereabouts and movements of the Red Navy for Luftwaffe dive-bombers, which, with participation from Escadrila 102, extirpated Soviet submarines from the Black Sea by late fall 1941.

Throughout 1942, the Corpul Aerian Roman was part of the Axis advance that swept irrepressibly across Russia toward the Don River Basin. Although its pilots continued to score heavily against the Red Air Force, they faced a growing crisis in the shortage of parts and aircraft. Before year’s end, most of their mounts were worn out beyond operational use, and the homeland’s industrial production of IAR 80s could not keep pace with the rate of attrition. Polish PZL fighters, now totally obsolete, were retired from frontline positions and relegated to training duties. Once lost or badly damaged, British warplanes in service with the Romanians could not be replaced after they opened hostilities against the Western Allies. The Wehrmacht, in its conquest of Greece, captured some Hawker Hurricanes, Bristol Blenheims, and Supermaine Spitfires, and these were duly dispatched to Grupl Aerien de Lupa squadrons on the Eastern Front.

The Germans also contributed all the Potez and Bloch bombers that survived 1940’s French Campaign in reasonably good condition, but these measures could not entirely meet replacement needs. Repeated requests for Luftwaffe aircraft were turned down on the grounds that the Geschwaeder were themselves inadequately equipped. In truth, Hitler did not share his best weapons with the Romanians, because he knew that their inveterate hatred for fellow Axis ally, Hungary, could flare into armed conflict at any moment, thereby jeopardizing the entire Campaign. His mistrust of them softened only because of their energetic participation in the debacle at Stalingrad, when he allowed Reichsmarschal Goering to send the first of 115 D-series Stukas to the FRAR.

Both on the ground and in the air, the Romanians accompanied German and Italian forces toward the infamous city. Based at Karpovka from early September to mid-November 1942, Corpul Aerian Roman fighter pilots escorted Axis bombers. Four or five missions were flown daily, although enemy opposition was rarely encountered, because Red Air Force losses over the previous 15 months had drastically reduced its effectiveness, and Stalin was hording surviving warplanes for a decisive offensive he planned to spring on the invaders. Their intensive bombing of his namesake city made him lose his temper, and he prematurely threw a powerful wave of interceptors at the relentless enemy overhead.

These consisted mostly of Russia’s best fighter, the Yak-lb, a step up over earlier variants with heavier armor, a control column copy of the Messerschmitt-109’s stick, and retractable tail-wheel that allowed for slightly increased speed. Its Klimov M-105PF liquid-cooled, V-12 engine generated 1,880 hp for a maximum speed of 368 mph but stalled when negative-G forces pinched off the flow of fuel-unfortunately for Soviet pilots, because negative-G forces were by then part of aerial confrontations.

The plywood warplane built on a steel frame, not surprisingly, suffered structural problems, which could lead to its mid-air disintegration under stressful maneuvers. Vibration additionally caused the spot-welded fuel tanks to leak, leading to on-board fires (not a good thing in a wood airplane), and pilots were unable to open the canopy at high speeds, preventing them from bailing out once the aircraft went into a dive. Their short-range radio was so unreliable they often ditched it to save weight, contributing to the Russians’ already chaotic field communications dilemma. Despite these considerable drawbacks, the Yak was better at the time than any other fighter in the Red Air Force-faster and quicker, delivering a powerful punch with its 20-mm ShVAK cannon and single 12.7-mm Berezin UBS machine-gun.

In five days-from September 12-17, 1942-the Romanians shot down 38 Soviet interceptors, mostly Yak lbs, for the loss of just one IAR-81, the victim of a desperate ramming attack. Thereafter, Axis bombers resumed their devastation of Stalingrad unmolested.

The situation changed radically on November 19, when Stalin’s winter offensive fell with all its overwhelming fury on the Romanian 3rd and 4th Armies, which were quickly surrounded. While repeated bombing and strafing runs were conducted to save their fellow countrymen on the ground, the airmen were in danger of having their own base overrun by the enemy. After sunset on November 22, a Russian reconnaissance vehicle was destroyed by Romanian flak guns as it approached the airfield, alerting its defenders to impending attack. In the predawn hours of the next day, as a veritable horde of tanks rumbled toward Karpovka, radios and as much armor as possible were stripped from each of the 16 Messerschmitt-109Es to make room for another pilot or mechanic in the cockpit.

The airmen had not been trained in night-flying techniques, but the approaching T-34s left them no alternative. The tanks fired on and hit the first Emil endeavoring to take off, and two other aircraft collided in the darkness. Abundant flames rising from these calamities sufficiently illuminated the airstrip for the other 13 fighters to take off. Their escape was covered by the suppressive fire of the flak gunners left behind, who fought to the death at Karpovka.

Throughout December 1942, Romanian transports undertook as many as 50 flights per day to relieve their fellow countrymen and Germany’s 6th Army trapped by the Russians. Braving appalling weather conditions and interdiction by Red Air Force fighters, civilian pilots and planes from LARES, Romania’s national airline, continued relief efforts after too many military transports were lost. Every IAR 81, an improved variant of the “80” additionally armed with a pair of Mauser MG 151/20 20-mm cannons, of Grupl 6 threw themselves on enemy ground forces in repeated low-level attacks from December 12-13, as Panzergruppe Hoth attempted a breakthrough to the encircled 6th Army.

The Soviets responded with a new offensive against the understrength Italian 8th Army, and the entire front burst like a lanced boil. On Christmas Eve, the Red juggernaut over-ran the Grupi Aerien de Lupa’s main airfield at Tazinskaya, effectively crippling Romanian air operations on the Eastern Front. Surviving aircraft operated over Stalingrad to the last day and virtually the last pilot. On February 20, 1943, just three fighters remained for evacuation from Grupi 7 behind the lines to Stalino. It was a tragic end to the vdnatori on the Eastern Front. Although the Gruparea Aeriana de Lupta was to soldier on in Russia, undertaking a variety of missions from liaison and transport to bombing and reconnaissance duties, the fighters were recalled home to protect their Motherland from anticipated Anglo-American raids.

Hitler wholeheartedly endorsed the Romanians’ departure, because they were necessary to protect the Ploie~ti oil fields, upon which his entire war machine depended. Impressed by the Romanians’ contribution to the battle, he allowed them to operate modern Luftwaffe aircraft for the first time. By early spring, the backbone of the German bomber force, the Heinkel He. 111 H-3, began appearing in growing numbers with Grupul 6 of Romania’s Corpul1 Aerien then operating throughout the Ukrainian Zaporozh’ye area.

The Fuehrer encouraged Mussolini to join him in assisting the Romanians, whose 3rd Air Corps received the first 24 of 48 SavoiaMarchetti SM.79-JRs from Italy. This was a twin-engine version of the trimotor Sparviero. Versatile beyond its original role, the JR version was powered by a French pair of 1,000-hp W Gnome-Rhone Mistral Major 14 K engines for mostly transport duties. Its long range (2,110 miles) and rugged construction were so favored by the Romanians, they built another 16 Sparrowhawks themselves under license.

In June, Grupl 3 was outfitted for the first time with Junkers Ju-87D Stuka dive-bombers on behalf of operations over the Straits of Kerch, on the eastern tip of the Crimea, where German and Romanian troops were endeavoring to hold the Kuban bridgehead. The same Grupl also received the latest version of Henschel’s Hs 129, the B-2/R2, purpose-built for the tank-busting role. Armed with two MC 151/20 20-mm cannons, a pair of MG 17 7.92-mm machine-guns and a single MK 101 30-mm cannon slung under the fuselage, the twin-engine aircraft featured a windscreen made of 75-mm armored glass and an armor-plated nose section. In the hands of Grupl3 pilots, the Hs.129 became the scourge of Russian ground forces. An aviation writer, Werner Neulen, observed, “its operations were to bring Soviet tank and infantry attacks to a halt time and again.

In late October 1943, Grupl 8 flew to the rescue of the Romanian 24th Infantry Division, which had been cut off on the isthmus between Perekop and Genitsesk. IAR 81 pilots softened up the Soviet encirclement sufficiently to allow for the breakout of 10,000 of their comrades on the ground. A far greater challenge of a similar kind came just a few days later, on November 1, when seven Romanian divisions and the entire German 17th Army were cut off from the Crimea by a Red Army offensive against the Dniepr. A Luftwaffe-FRAR air bridge of mostly Junkers-52 trimotors evacuated 21,937 troops, until the Crimea fell six months later, in early May 1944.

By then, German assistance had grown generous, allowing the Grupl Aerien de Lupa to receive enough of the latest Messerschmitt Bf 109Gs to completely make up for all fighters lost in action. But these additions, however welcome, could not stem the Red tide flowing westward. As some measure of the desperation that characterized the Axis at this time, Executive Officer Ian Milu’s Messerschmitt Gustav destroyed three LaGG-3s in two different engagements involving 10 Soviet interceptors on May 6 after he completed a successful bombing run. Milu would go on to down 52 enemy aircraft, becoming his country’s third, top-scoring ace and achieving a record number of “kills”-five Soviet warplanes-in one day.

On May 14, Grupl 3 Stukas destroyed a bridge about to be crossed by Soviet troops over the Prut River, Romania’s pre-war boundary with the USSR. On the 30th, Grupl 6 transferred from Krosno, in Poland, to participate in joint sorties against enemy armor and artillery, flying 93 missions in 24 hours. June 1 saw 69 Romanian Stukas blast the serried ranks of T-34 tanks to begin a week of non-stop attacks. The lull in action that followed was just the quiet before the storm, however, as the battered but immense Soviet Army Group South Ukraine prepared its offensive for subjugating the Balkans. Meanwhile, opposition elements-including a Moscow-directed underground-in the monarchy at Bucharest plotted to extricate their country from impending invasion.

WorldWar2.ro

Romanian Armed Forces in the Second World War