Paul Hausser, the man who had perhaps the single greatest influence in the military development of the Waffen-SS, was born in Brandenburg on October 7, 1880, the son of a Prussian officer. He was educated in military prep schools and in 1892 enrolled in Berlin-Lichterfelde, Imperial Germany’s equivalent of West Point. Among his classmates were future field marshals Fedor von Bock and Guenther von Kluge.

Hausser graduated in 1899 and, as a second lieutenant, was assigned to the 155th Infantry Regiment in Ostrow, Posen. After eight years of regimental service he entered the War Academy in 1907 but did not graduate until 1912. In the interval he returned to his regiment and also underwent coastal defense and aerial observer training. He was assigned to the Greater General Staff in 1912 and was promoted to captain in 1914. Later that year, when the German Army mobilized for World War I, Hausser was assigned to the staff of the 6th Army, commanded by Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria. Later he served on the staff of the VI Corps, as Ia of the 109th Infantry Division; with the I Reserve Corps (also as Ia); and as a company commander in the 38th Fusilier Regiment. He fought in France, Hungary, and Rumania and was awarded both classes of the Iron Cross. At the close of hostilities, he was Ia of the 59th Reserve Command at Glogua, Germany. After the war he served with a Freikorps unit on the eastern frontier before joining the Reichsheer in 1920.

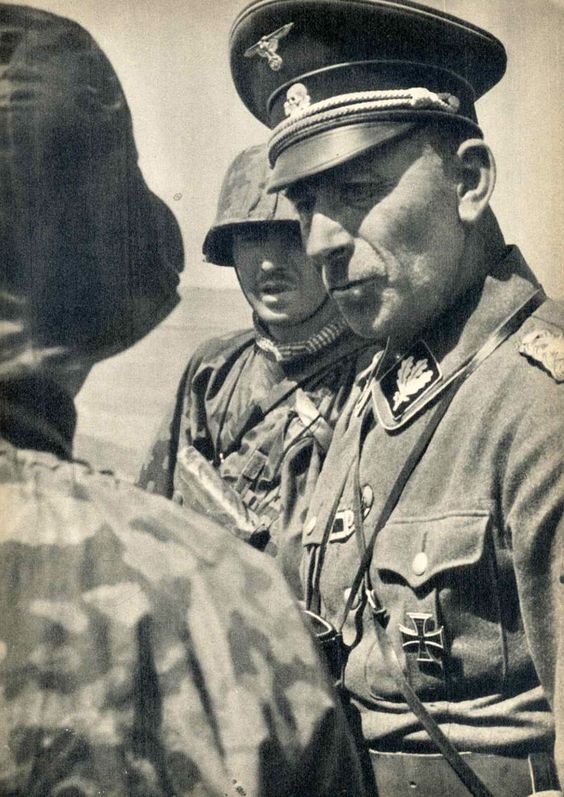

During the Reichswehr era, Hausser was on the staff of the 5th Infantry Brigade (1920-1922); Wehrkreis II at Stettin, Pomerania (1922-1923); 2nd Infantry Division, also at Stettin (1925-1926); and the Saxon 10th Infantry Regiment at Dresden (1927). He also served as commander of the III Battalion, 4th (Prussian) Infantry Regiment at Deutsch-Krone (1923-1925), and 10th Infantry Regiment (1927-1930), and ended his army career as Infantry Commander IV (Infanteriefuehrer IV) at Dresden, a post he held from 1930 to 1932. In this last post he was simultaneously one of the two deputy commanders of the 4th Infantry Division. He retired as a major general on January 31, 1932, at the age of 51, with the honorary rank of lieutenant general. At this point in his career, Paul Hausser-who had always been a fervent German nationalist-became involved with the Nazi Party. By 1934 he was an SA Standartenfuehrer and brigade commander in the Berlin-Brandenburg area, when Heinrich Himmler offered him the job of training his SS-Verfuegunstruppe (SS-VT, or Special Purpose Troops)-the embryo of the Waffen-SS. Hausser entered the SS as a Standartenfuehrer of November 15, 1934. His first assignment was that of commandant of the SS-Officer Training School (SS-Junkerschule) at Braunschweig (Brunswick).

In the SS-VT, Hausser found enthusiastic but untrained young Nazis who were fanatically dedicated to their Fuehrer and were most willing to be shaped into a cohesive military organization. As a former General Staff officer, Hausser possessed command and organizational experience, both of which were needed and appreciated. He quickly organized the curriculum of the school into a model copied by all SS officers, NCOs, and weapons schools throughout Germany-and later throughout Europe. Hausser’s program emphasized physical fitness, athletic competition, teamwork, and a close relationship between the ranks-a degree of comradeship that did not exist in the German Army at that time. Hausser himself was a noted sportsman and equestrian who could successfully compete with men 30 years his junior. Under his leadership, the SS elite soon exceeded anything the army could field-at least in appearance. Himmler was so impressed that he named Hausser inspector of SS Officer Schools, in charge of the officer training establishments at Brunswick and Bad Toelz, as well as the SS Medical Academy in Graz. He was promoted to Oberfuehrer on April 20, 1936 (Hitler’s birthday) and to Brigadefuehrer in May 1936. Later that year, due to the rapid expansion of the SS, he was appointed chief of the Inspectorate of SS-VT and was responsible for the military training of all SS units except those belonging to Theodor Eicke.

Hausser proved to be an intelligent and professionally broad-minded director of training. It was he, for example, who saw to it that the SS-VT were the first troops to wear camouflaged uniforms in the fields, and he stuck to his decision, even though the army’s soldiers laughed and called the SS men “tree frogs.” (These uniforms were very much like the present-day U. S. Army battledress uniforms [BDUs, or “fatigues”].) During the next three years he oversaw the organization, development, and training of the SS regiments “Deutschland,” “Germania,” and “Der Fuehrer,” as well as smaller combat support, service, and supply units. Paul Hausser was quick to see the potential of the blitzkrieg and, as a consequence, most of the SS units were motorized. In the autumn of 1939, he was in the processes of forming the SS-VT Division, but the outbreak of the war caught him by surprise, and not all his units had completed their training; consequently, no SS division as such fought in Poland. Most of the combat-ready SS-VT units (and Hausser personally) were attached to the ad hoc Panzer Division “Kempf,” led by army Major General Werner Kempf. After this campaign the first full Waffen-SS division was established at the Army Maneuver Area Brdy-Wald, near Pilsen, on October 10, 1939. Its commander was the recently promoted SS-Gruppenfuehrer Paul Hausser.

Hausser trained his SS-VT Motorized Infantry Division throughout the winter of 1939-1940 and led it with some distinction in the conquests of Holland, Belgium, and France in 1940, during which it pushed all the way to the Spanish frontier. As a result of the successes of the Waffen-SS units in these battles, Hitler authorized the formation of the new SS combat divisions in the winter of 1940-1941. The SS-VT Division (now on garrison duty in Holland) provided the nucleus for these divisions, giving up a motorized infantry regiment and several smaller units in the process. Meanwhile, in December 1940, the SS-VT was transferred to Vesoul in southern France and redesignated SS Division Deutschland; however, this name was too easily confused with the regiment of the same name, so in early 1941 it became SS Panzer Division “Das Reich.”

Paul Hausser did not complain about losing almost half his veteran soldiers, but rather devoted himself to training their inexperienced replacements for the planned invasion of England. In March 1941, however, the Reich Division was transferred to Rumania and took part in the conquest of Yugoslavia in April. Hurried back to Germany, it was quickly refitted for Operation Barbarossa and was then sent to assembly areas in Poland, where it was still in the process of reforming on June 15.

The invasion of the Soviet Union began on June 22, 1941. Hausser crossed the border near Brest-Litovsk and took part in the battles of encirclement in the zone of Army Group Center. The Reich Division distinguished itself in extremely heavy combat. In July alone it destroyed 103 tanks and smashed the elite Soviet 100th Infantry Division. By mid-November the Reich had suffered 40 percent casualties, among them the divisional commander. Paul Hausser was severely wounded in the face and lost his right eye in a battle near Gjatsch on October 14. He was evacuated back to Germany, where it took him several months to recover.

Hausser (now an Obergruppenfuehrer) returned to active duty in May 1942, as commander of the newly created SS Motorized Corps, which became the SS Panzer Corps on June 1, 1942. Hausser was thus the first SS man to become a corps commander. He spent the rest of 1942 in northern France, controlling the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd SS divisions (the Leibstandarte, Das Reich, and Totenkopf divisions, respectively). Among other things these superbly equipped units were given a panzer battalion and a company of the first PzKw V (“Tiger”) tanks.

While Hausser prepared his new command for its next campaign, disaster struck on the Russian Front. Stalingrad was surrounded, the Don sector collapsed, and the Red Army poured through Axis lines, heading west. In January 1943, Hitler rushed the SS Panzer Corps to Kharkov, the fourth-largest city in the Soviet Union, which, for reasons of prestige, he ordered to be held to the last man. “Now at last Hitler was reassured,” Paul Carell wrote later. “He relied on the absolute obedience of the Waffen-SS Corps and overlooked the fact that the corps commander, General Paul Hausser, was a man of common sense, strategic skill, and with the courage to stand up to his superiors.”

By noon on February 15, Hausser was almost surrounded by the Soviet 3rd Tank and 69th armies. Rather than sacrifice his two elite SS divisions (Totenkopf had not yet arrived from France), Hausser ordered his corps to break out to the southwest at 1 p. m., regardless of Hitler’s commands or those of the army generals.

Hausser’s immediate superior, Army General Hubert Lanz, was horrified by this development. A Fuehrer Order was being deliberately disobeyed! At 3:30 p. m. he signaled Hausser: “Kharhov will be defended under all circumstances!”

Paul Hausser ignored this order as well. The last German rearguard left Kharkov on the morning of February 16. Hausser had made good his escape and had saved the army’s 320th Infantry Division and its elite Grossdeutschland Panzer Grenadier Division in the process. The question now was how Hitler would react to this piece of deliberate insubordination.

Adolf Hitler’s mentality demanded that a scapegoat be found for this latest disaster, but Hausser was not a candidate for public disgrace. After all, he was an SS officer, a loyal Nazi, and a holder of the Golden Party Badge, which Hitler had conferred on him just three weeks before. Instead, Hitler sacked none other than Hubert Lanz, the very officer who had insisted to the last that the Fuehrer’s order be obeyed. Contrary to usual practice, however, Lanz was given command of a mountain corps shortly thereafter, instead of being permanently retired.

Hitler did not forgive Hausser quickly, however, even after reports and events of the next few days made the correctness of his actions clear for all to see-even at Fuehrer Headquarters. As punishment, a recommendation that Hausser be decorated with the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross was not acted upon.

Meanwhile, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, the commander of Army Group South, devised a brilliant plan to restabilize the southern sector of the Eastern Front. Realizing that the overconfident Soviets were in danger of outrunning their supply lines, he allowed them to surge forward, while he hoarded his armor for a massive counterattack. This stroke would entail a pincer movement to cut off the massive Soviet penetration south of Kharkov, followed by an attempt to recapture the city. Hausser, now reinforced with the SS Totenkopf Division, would command the left wing of the pincer.

The Third Battle of Kharkov began on February 21, 1943. The fighting was fierce, but by March 9 the Soviet 6th Army and Popov Armored Group had been destroyed-a loss of more than 600 tanks, 400 guns, 600 anti-tank guns, and tens of thousands of men. That day Paul Hausser’s spearheads reentered the burning city of Kharkov, beginning the most controversial battle of the general’s career. Military historians generally agree that Kharkov was now doomed and that Hausser should have encircled the city; instead, he attacked it frontally from the west and began six days of costly street fighting against fanatical resistance. The conquest of Kharkov was not complete until March 14. During the battle, the SS Panzer Corps suffered 11,000 casualties, against 20,000 for the Red Army.

Hausser redeemed his military reputation that July, during the Battle of Kursk-the greatest tank battle in history. His command, now designated II SS Panzer Corps, penetrated farther than any other German unit and destroyed an estimated 1,149 Soviet tanks and armored vehicles in the process. Colonel General Hermann Hoth, the commander of the 4th Panzer Army, recommended him for the Oak Leaves, stating that despite being handicapped by his previous wounds, he “untiringly led all day from the front. By his presence, his bravery and his humor, even in the most difficult situations, he imbued his troops with buoyancy and enthusiasm, yet he kept command of the corps tightly and in his hand. . . . [Hausser] again distinguished himself as an unusually qualified commanding general.”

While the Germans were being defeated at Kursk, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was overthrown on July 25. Hitler ordered the II SS Panzer Corps to transfer to northern Italy on the same day, although in the end only the corps headquarters and the 1st SS Panzer Grenadier Division ever left the Eastern Front. Hausser remained in Italy until December 1943, without engaging in any fighting; then he was transferred to France, where his corps took charge of the recently organized 9th SS Panzer Division “Hohenstaufen” and the 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg.”

Hausser’s corps was supposed to be held in reserve to oppose the D-Day invasion, but when the 1st Panzer Army was surrounded in Galicia in April 1944, Hausser was sent back to the Eastern Front to rescue it. This was accomplished without too much difficulty, thanks to Manstein, Hausser, and the army’s commander, Hans Valentin Hube. Instead of sending the SS corps back to France, however, Hitler sent it to Poland, where it formed a reserve against the Soviets. It was not until June 11-five days after the Allies’ D-Day landings-that Hitler ordered the corps back to France. It was assigned a sector west of Caen, with the mission of holding the critical Hill 112.