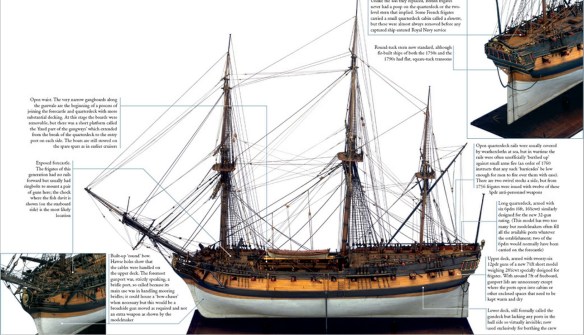

This highly detailed model of the Lowestoffe, launched in 1761, represents Sir Thomas Slade’s final thoughts on the 12pdr 32-gun frigate. The hull form was developed from that of a French prize, the more upright stem and sternpost being obvious features, but the midship section is more difficult to appreciate in a photograph. The French employed a characteristic transverse shape with sharp angles at the ends of the floors and around the load waterline, combined with excessive tumblehome (the curving in of the topsides), but it is notable that the British avoided the extreme versions of this ‘two-turn bilge’, preferring more rounded versions with less tumblehome. In Lowestoffe Slade produced a very fast ship, but she was only a slight improvement over his already excellent Niger class.

The Niger class was a notable improvement over the first two 32-gun designs, but the principal advantage was in the hull form, which is not easy to appreciate in this model of Winchelsea. What is more obvious is the hawse brought in on the upper deck, with a round bow and a lighter and more raised head as a consequence. Although there are still only thirteen broadside gunports, there is a chase port right forward, presumably to replace a position firing over the beakhead bulkhead. One minor problem with the round bow was that the catbeam (connecting and supporting the catheads that had been fitted across the top of the beakhead bulkhead) had to be replaced by angled extensions run under the forecastle beams so they did not obstruct the deck. Apart from the carriage guns, these ships were issued with twelve ½pdr swivel guns, and their stocks can be seen above gunports 1, 3, 12 and 13; they could also be fitted in the fighting tops.

The First 12-pounder Frigates

The Unicorn and Lyme set a number of important administrative precedents: first, that the Admiralty could depart from the Establishment if it felt the need; second, that it could determine the design (by insisting that a particular model be copied); and third, by extrapolation, that in future there would always be more than one source of design. Henceforth, there were always to be at least two Surveyors during wartime, and when there was only a single incumbent, he was supported by a highly regarded Assistant Surveyor who was clearly seen as a full Surveyor-in-waiting. In this case, the comparative principle was honoured by allowing Acworth and Allin, the two Surveyors in post, to design their own alternatives to the French-derived pair, equally untrammelled by Establishment restrictions. Both the resulting Seahorse from Acworth and Allin’s Mermaid were a conceptual halfway house between the old 24s and the new frigate form – they had no gunports on the lower deck but, having much the same headroom between decks, the height of side was not significantly reduced, and being shorter than the Unicorns, they did not perform so well. When the time came to build more Sixth Rates in 1755, there was no debate about which model to chose, and two slightly modified Unicorns were ordered. Now rated 28s, this type became the standard light cruiser for over two decades.

In the interim a parallel argument was developing about the Navy’s heavy cruiser, the two-decker 44-gun ship. As early as 1747 the Navy Board was fending off suggestions that a frigate-form ship would be preferable, arguing – as they had in defence of the three-decker 80 – that multiple decks made them better fighting ships: there was more room on the gundecks to work the guns, and the crews were better protected than those on the long exposed quarterdecks and forecastles of frigates. They were prepared to admit that, being taller and more heavily built, British 44s were not such good sailers, but they denied that they could not open the lower deck ports in any sort of seaway – their lower tier could be opened in ‘any fighting weather’ and their battery of twenty 18pdrs was superior to the thirty 12pdrs proposed. Furthermore, as these two-deckers were often convoy escorts as well as cruisers their defensible qualities were as important as speed under sail.

As so often, France took the lead by building the Hermione, the first 12pdr frigate, in 1748, and thereafter no more French two-decker 40s were ordered. However, there was clearly a degree of uncertainty about the ideal size, armament, and even design features, of the new type. The first ship, measuring 811 tons by British calculation, had an unusually deep hull, with six ports on the lower deck when captured in 1758 (although none was armed; the ship may have been built with oar ports on this deck) and a main battery of twenty-six 12pdrs. The next ship was rather smaller with only twenty-four guns, while the two after that were far larger and carried thirty 12pdrs. There was never to be a remotely standard French 12pdr frigate, although a typical ship would measure about 900 tons and carry twenty-six 12pdrs and six 6pdrs on the quarterdeck.

By contrast the Royal Navy knew exactly what it wanted from its first 12pdr frigates, the specification being ships of about 650 tons and a battery of twenty-six 12pdrs; the dimensions did not vary by more than about 10 per cent during the three decades such ships were built. The disparity in size was partly the product of the typical British policy of building the smallest viable unit (so the maximum number could be built for any given budget), but in any case the true comparison is not with the handful of 12pdr ships France built before 1764 but the substantial numbers of large but 8pdr-armed frigates that formed the core of the French frigate force during the Seven Years War.

By 1755 both Acworth and Allin were dead and had been replaced by joint Surveyors of a far younger generation in Thomas Slade and William Bately. Following the new comparative policy, each was set to produce a draught to the same general specification for a 32-gun ship of about 125ft on the gundeck. Bately, a competent but unoriginal thinker, produced a slightly longer, narrower and shallower hull form based on a long-established fast-sailing tradition preserved in the yacht Royal Caroline but ultimately derived from Lord Danby’s work at the beginning of the century. His Richmond was a modest success, despite not being as fast as expected, and six ships were built to this draught during the war; astonishingly, the design was revived in 1804 for a further eight ships when it was decidedly obsolescent, although it has to be said that at the time a small, cheap design was politically expedient.

Slade, who by both contemporary and historical judgement was to become the best British ship designer of the century, did not excel with his first frigate class. Apparently a genuinely ab initio design based on no existing model, the Southampton class were strong, good sea-boats and performed well in heavy weather, but lacked speed. However, Slade’s most notable characteristic as a designer was a constant search for improvement, a self-critical faculty manifest in the many alterations to be found on his draughts. Often the advance was incremental – as seen in the many variants on his standard 74-gun ship classes – but in this case he took an entirely different starting point, developing the lines from the Tygre-derived 28s for the next class. As alternatives, he had offered the Admiralty an improved Southampton or a hull based on the extreme French form of the Amazon, the 20-gun Panthère captured in 1746, but as he was called to the Admiralty to discuss the options, it is highly likely that the final decision was largely based on his own preference. It was a good choice: the resulting Niger design provided the best British 12pdr class and, in terms of fitness for purpose, probably the best frigates of the Seven Years War. They were fast, weatherly, very handy and strongly built; more of them (eleven) were ordered than any other design, and it is entirely appropriate that when Lord Sandwich commissioned a spectacular structural model he chose one of these to be the subject. The Winchelsea model [SLR0339], complete on the starboard side but with the port side unplanked to reveal how such ships were built, was presented to George III in 1774 as part of Sandwich’s campaign to interest the King in his navy.

All the demands that were to be placed on heavier frigates during the war were met, and with total satisfaction, by the 12pdr 32; but before this became clear there were a couple of trials with more powerful ships. In July 1756 three enlarged Southamptons were ordered as the Pallas class and rated as 36-gun ships. At around 720 tons, they were about 11 per cent larger (and because costs were calculated on a £ per ton basis, more expensive pro rata) yet they offered only four extra 6pdrs by way of firepower benefit over the standard 32. No more 12pdr 36s were ever ordered.

More radical was an attempt to find out if Slade could make an acceptable cruiser out of the two-decker 44, the single example being launched as the Phoenix in 1759. Longer and narrower than its 1745 Establishment predecessors, this ship was the only 44 built during the Seven Years War, so even the advantage of an 18pdr main battery was not considered valuable at this time.

By 1757 Slade enjoyed the complete confidence of the Admiralty and was allowed considerable autonomy over ship design, totally eclipsing Bately in the process. He was permitted to build a frigate on extreme French principles – ‘stretching’ the Tygre hull form by 10ft and using very lightweight framing – and the resulting 32-gun Tweed showed all the advantages and disadvantages of the French philosophy: she was fast, very wet, tender (lacking stability) and short-lived. It was almost as though Slade was providing his masters at the Admiralty with an object lesson in how to prioritise their requirements.

Slade’s final contributions to frigate design had a curious provenance. In 1757 the Navy had captured a very large 950-ton ‘frigate’ constructed in Quebec. Everything about this ship was strange – including her name, L’Abenakise, which the English tried to render as Bon Acquis or Bien Acquis, although she actually celebrated the Abenaki tribe, one of the principal Indian allies of French Canada. The ship herself, though new-built, was a demi-batterie ship, like the purpose-designed commerce-raiders of half a century earlier, with eight 18pdrs on the lower deck and twenty-eight 12s above. Despite the anachronistic layout, Slade inspected the ship and, ‘approving very much of the form of her body’, suggested that she would provide the model for an improved frigate design. Slade’s enthusiasm was so infectious that the Admiralty ordered draughts prepared for five new classes, from a 74 to a sloop. This required a further lesson for Their Lordships on the difficulty of simply scaling a set of lines up or down, but the resulting designs utilised the principles of the French form and were described as ‘nearly similar to the Aurora’, as the prize had been renamed.

Both new frigate designs, the 28-gun Mermaid and the 32-gun Lowestoffe were slightly larger than existing ships but not the radical improvement Slade had hoped for.