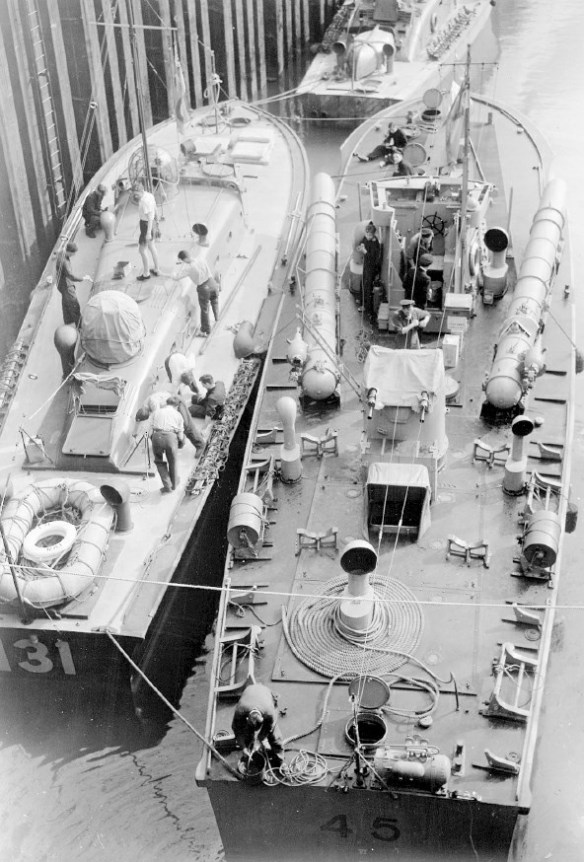

Op Ambassador. An RAF crash launch moored alongside an MTB, with another one just ahead. It shows clearly how much smaller they were, so no wonder they were damaged by a destroyer’s wake when moving at speed.

The immediate reaction to the PM’s memo was that Second Lieutenant Hubert Nicolle, late of the Guernsey Militia and now in the Hampshire Regiment, landed at le Jaonnet Bay on the south coast of Guernsey on 5 July. Despite the almost farcical beginning of his operation (it was reputed that he had to purchase his own folding canoe from Gamages, before going to Plymouth to board a submarine.) it was remarkably successful. He met up with two old friends who agreed to help him. One was his uncle, who was the assistant harbour master at St Peter Port, and was thus able to give him reliable information on the naval situation; whilst the other, a local baker who supplied bread to the Germans gave him the exact ration strength (469 all ranks) plus their locations – main body in St Peter Port with the rest manning machine gun posts around the island. His was only a reconnaissance mission which included checking on the suitability of the landing site for the main operation (to be codenamed: AMBASSADOR). He would be replaced by two more ex-Guernsey Militia who would then stay on the island and be ready to guide a large raiding party composed of No 3 Commando under Lieutenant Colonel John Durnford-Slater. This officer (later Brigadier, DSO and Bar) was in fact the very first commando soldier of the war, having been promoted from Captain to Lieutenant Colonel and chosen to raise and command No 3 Commando (Nos 1 & 2 did not at that time exist). As he explains in his autobiography:

‘I had wanted action: I was going to get it. I should have been delighted to join at any rank, but was naturally pleased to get command. I was confident I could do the work and made up my mind to produce a really great unit.’

Back in Guernsey all was going well, the two new men (Second Lieutenant Philip Martel and Second Lieutenant Desmond Mulholland) arrived safely on the night of 9/10 July in the same manner as Nicolle via submarine and folding boat, and after he had briefed them, he rowed out to the submarine which had brought them to Guernsey, leaving them on the shore. Unfortunately, from that moment onwards, everything started to go wrong. The raiders were due to arrive on the night of 12 July, meet their guides, assault the aerodrome burning aircraft, destroying fuel stocks, etc. However, bad weather delayed the operation for 48 hours during which time it was impossible to contact the two guides. After they had hidden for two days they returned to the beach, found no one there and nothing happening. They realised that something had gone seriously wrong so decided to steal a boat and try to get away, rather than putting their innocent families, who still lived on Guernsey, at risk. So, whilst they hid – first in a barn then in a house – near Vazon Bay, word was passed to Dame Sibyl Hathaway in Sark, whose son in law and daughter owned the house in which they were hiding, to ask for her help. She tells in her memoirs how she took some tinned supplies over to Guernsey, pretending to be in charge of her daughter’s property. She met the two men who asked her if she could arrange for a fishing boat from Sark to pick them up, and she had the unenviable job of telling them that was impossible as the Germans guarded all the fishing boats very carefully. Also, it was impossible to get sufficient petrol. Despite this setback Martel and Mullholland managed to steal a boat at Perelle Bay – just west of Vazon Bay – but it was smashed to pieces on the rocks and they were left stranded. They would be forced to give themselves up before they could be rescued.

Whilst this drama was taking place, the main operation, Op AMBASSADOR, was suffering its own setbacks. In view of the 48 hour delay, the plan had to be amended. The original idea was for a force of forty men from 3 Commando, under Captain de Crespigny, to land first and create a diversion, whilst No 11 Independent Company attacked the airfield. This company would be split into two groups, the larger group of sixty-eight men, under Major Todd, would come ashore at Moye Point directly south of the airfield, whilst the rest of the company (another twenty men under Captain Goodwin) landed a mile or so further west. Two destroyers, HMS Scimitar and Saladin would transport them and escort seven RAF sea rescue launches (known as ‘crash boats’) that would take the men from ship to shore.

On the morning of 14 July, the intended day of departure, an officer sent from the Combined Operations Staff in London intercepted Durnford-Slater and told him that everything had changed, because they had discovered that the German garrision had been reinforced just where his commandos intended to land. Nothing daunted, a new plan was worked out on the spot, the force would now land at Petit Port on the south side of the island in Moulin Huet Bay, and departure was fixed for 1800 hours that evening. After completing all their preparations – assisted by some cadets from the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, they set off on a lovely summer’s evening. ‘Lieutenant Joe Smale’s party was to establish a roadblock on the road leading from the Jerbourg Peninsula to the rest of the island,’ wrote Dornford-Slater in his autobiography, ‘so that we would not be interrupted by German reinforcements. My own party was to attack a machine gun post and put the telegraph cable out of action. Captain de Crespigny was to attack the barracks situated on the peninsula and Second Lieutenant Peter Young was to guard the beach. Peter did not relish this job as he wanted more action. ‘All right’ I told him, ‘if it’s quiet come forward and see what’s going on.’

As the party left harbour more problems began to occur. Two of the crash boats were found to be unfit and had to be left behind, which meant reorganising the loading details, transferring stores between boats and deciding that some of the crash boats would need to make at least two journeys inshore. The whaler of HMS Scimitar would also have to be used to ferry the commandos ashore. The convoy was about fifteen minutes late in starting and then was further delayed as one of the crash boats had to wait behind for stores and didn’t then catch up until just before last light. It was a moonless night, so they did not see the Island until they were only some two miles away when the south coast suddenly appeared out of the gloom looking: ‘…dark and foreboding’. At about 0045 hours Durnford-Slater fortunately recognised the gap in the cliffs and was able to fix the place where they would climb up them. They clambered down rope netting on the side of their destroyer and boarded their launches in a calm sea. He comments: ‘It was dead easy.’

However, the other party was not having such an easy time, having missed Guernsey completely and also having problems with the crash boats which were leaking badly. One of the commandos in this group was Sir Roland Swayne MC, then a young officer in the Herefordshire Regiment, who had been selected for commando training. His recollections of AMBASSADOR were recorded by the IWM Department of Sound Archives and he makes the point that it was the method of transportation which had let them down:

‘It was beautifully planned from an army point of view but the naval preparation was very inefficient, partly due to inadequate equipment of course. … it was a wonderful idea and it could have been a very, very clever raid. But the means of transport were absolutely hopeless. They towed gigs and whalers and I think the crash boats were towed – they may have gone under their own steam – but the gigs and whalers were towed by destroyers. Well, of course, it was much too fast for them and they got damaged going there. And when we got out from the destroyer into these boats they were all leaking. We decided to put into Sark and anyhow get rid of half the people on board so that there was a chance of this boat getting back to England under its own steam. And we were making for Sark when the destroyer spotted us. Somebody on the destroyer – it was a soldier actually – spotted something in the water. He knew that there were people missing and he drew the attention of a ship’s officer and he got the ship diverted to pick us up and we got home. It was very lucky we got home.’

Everything had also started to go wrong for Durnford-Slater. The pair of launches carrying his party had left the destroyer and set off on the agreed course, the naval officers in charge of the launches carefully watching their compasses rather than the coastline. Durnford-Slater soon realised that they were heading out to sea in the direction of France.

‘“This is no bloody good”, I said to the skipper of our launch, “we are going right away from Guernsey.” He looked back and saw the cliff. “You’re right! We are indeed. It must be this damned de-gaussing arrangement that’s knocked the compass out of true. I ought to have it checked.” “Don’t worry about the compass,” I said, “let’s head straight for the beach!”

Thereafter they navigated by eye and were soon just about 100 yards from the shore. They had another scare when a large half-submereged rock was mistaken for an enemy submarine, but their real problems came when the boats, which did not have flat bottoms, grounded on rocks instead of smooth sand – their 48 hour delay having affected the state of the tide – so they had to jump out into armpit-deep water! They struggled ashore, with not a dry weapon amongst them and started to climb up a long flight of stone steps towards the houses at the top. As they reached them the neighbourhood dogs began to bark, but fortunately an Avro Anson aircraft began to circle right above them (this was part of the agreed cover plan) which helped to deaden the noise they were making. It worked! They reached the machine gun nest and the cable hut but found them both unoccupied. It was the same at the barracks – no one at home! Disappointed, they realised that they were now running well behind schedule, so decided to abort the mission and head for home. On the way down the steps, Durnford-Slater, who was at the rear, tripped and fell, his cocked revolver going off accidentally. This at last produced some reaction from the Germans, who started firing their machine guns out to sea, whilst the commandos were forming up on the beach to reembark.

Getting away proved to be just as difficult. Because of the rocks, the launches could not get near enough and men and weapons had to be ferried out in one small dinghy, until it was dashed on the rocks and everyone had to swim for it. Somehow they managed to reach the launches and were pulled to safety. But the drama was not yet over. They were by now much later than had been anticipated, indeed the destroyers had already reluctantly decided to head for home, but the captain of HMS Scimitar made one last sweep and fortunately saw their frantic torch signals, came to the rescue and the bedraggled party was saved. All that is except for four men – Commandos Drain, Dumper, McGoldrick and Ross, who couldn’t swim – what an admission for a commando to have to make. They were left behind, managed to evade capture for a few days, hoping to be picked up, but were eventually arrested while walking down the road to the aerodrome in broad daylight and finished the war in Stalag VIIIB in Upper Silesia. This of course still left Martel and Mulholland and so another Guernseyman in England, Stanley Ferbrache, volunteered to try to rescue them. He was taken over in an MTB and landed at La Jaonnet on 3 August, made contact with his uncle, Albert Callighan and his mother, Mrs Le Mesurier, who told him that the two men had already given themselves up to the German authorities the previous week. Ferbrache collected all the information he could (he is reputed as even walking around the airfield perimeter unchecked), and was safely taken off Guernsey on the night of 6 August.

That was the end of the ill-fated Operation AMBASSADOR. Sir Roland Swayne comments in his taped interview that it was a ‘… brave idea’, but goes on to say:

‘but we weren’t remotely ready. We didn’t know what kind of boats we wanted, we didn’t know how to do it, there wasn’t a proper planning body to prepare for these raids. In any case there was a fearful shortage of weapons and everything… we had no Tommy guns and we didn’t have the Remington Colt which we were issued with later… we were armed with .38 revolvers which was, I always thought, a poor weapon. There was a shortage of ammunition for teaching the soldiers to shoot. Some of them had hardly done any practice on the range, it was all frightfully amateurish.’

His sentiments were echoed by the Prime Minister who was most displeased by the failure of Operation AMBASSADOR. He sent a scathing message to the HQ Combined Forces which included the words: ‘Let there be no more silly fiascos like those perpetrated at Guernsey.’ Next time they would have to do a great deal better – or else!