F-6D & F-6K

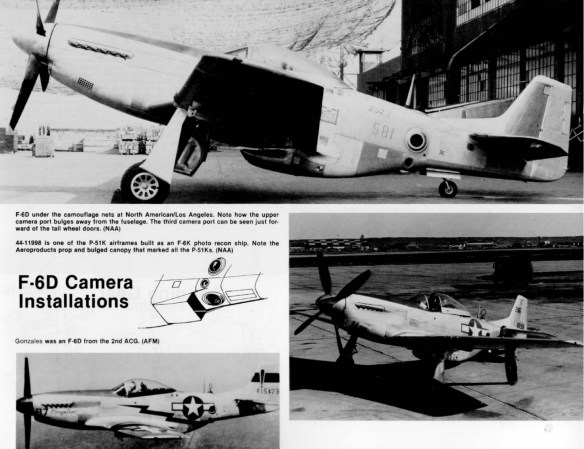

A total of 163 P-51Ks were completed as F-6K photo-reconnaissance aircraft. 126 Inglewood-built P-51Ds from blocks 20, 25, and 30 were converted after completion as F-6Ds. A few others were similarly converted near the end of the war. All of these photographic Mustangs carried two cameras in the rear fuselage, usually a K17 and a K22, one looking out almost horizontally off to the left and the other one down below looking out at at an oblique angle. Most F-6Ds and Ks carried a direction- finding receiver, serviced by a rotating loop antenna mounted just ahead of the dorsal fin. Most F-6Ds and Ks retained their armament.

In January 1940, the Luftwaffe tested the prototype Ju 86P with a longer wingspan, pressurized cabin, Jumo 207A1 turbocharged diesel engines, and a two-man crew. The Ju 86P could fly at heights of 12,000 m (39,000 ft) and higher on occasion, where it was felt to be safe from Allied fighters. The British Westland Welkin and Soviet Yakovlev Yak-9PD were developed specifically to counter this threat.

Satisfied with the trials of the new Ju 86P prototype, the Luftwaffe ordered that some 40 older-model bombers be converted to Ju 86 P-1 high-altitude bombers and Ju 86 P-2 photo reconnaissance aircraft. Those operated successfully for some years over Britain, the Soviet Union and North Africa. In August 1942, a modified Spitfire V shot one down over Egypt at some 14,500 m (49,000 ft); when two more were lost, Ju 86Ps were withdrawn from service in 1943.

Junkers developed the Ju 86R for the Luftwaffe, using larger wings and new engines capable of even higher altitudes – up to 16,000 m (52,500 ft) – but production was limited to prototypes.

THE NAZIS’ PHOTOGRAPHIC LEGACY

In May 1945 British and US units overran a number of Luftwaffe intelligence centres in the heart of the German Reich. They recovered a remarkable imagery collection covering the western part of the Soviet Union that had been assembled by the Luftwaffe. For the next two decades this photography was a vital part of British and American targeting intelligence. They gathered together this huge photographic collection, under Operations Dick Tracy and GX, from a number of dispersed locations. These ranged from a barn near Reichenhall, through partially burned photography found in barges, with some of the best said to be from Hitler’s retreat at Berchtesgaden and yet more from Vienna and Oslo. Totalling over 1 million prints it required nearly 200 officers to manage the collection. In October 1945 the duplication effort moved from Pinetree in Essex to RAF Medmenham in Oxfordshire. Work on piecing the material together continued beyond 1949. More photography was purchased from two unidentified ‘gentlemen of Europe’ in 1958 and Dino Brugioni mentions the discovery, of hitherto unknown material, moved from Berlin to a Dresden basement at the end of the war, which was found in 1993. The combined collection provided a detailed photographic record of Soviet Russia as far as the Ural Mountains and had begun to be amassed well before the Nazi invasion in 1941. Significant updating and replacement of this imagery was not possible until the advent of satellite imagery after 1960. This collection was the basis of the continuous Anglo-American photographic intelligence exchanges throughout the Cold War but was not restricted to just Soviet-focused material.

AMERICAN CORRIDOR AND OTHER RECONNAISSANCE FLIGHTS

The US airborne intelligence collection effort in Europe was huge. Between 1945 and 1990, USAFE flew around 10,000 flights in the Berlin Corridors and BCZ – an average of a flight every one and a half days, which dwarfed British and French efforts. USAFE also conducted ‘non-corridor’ ‘peripheral flights’, from Federal Germany, as far afield as the Baltic Sea in the north, along the IGB and Czech-German border and south to the Adriatic, the Mediterranean and Black and Caspian seas. It also managed early penetration overflights over Eastern Europe before the arrival of the U-2. This extensive programme was conducted in conjunction with the discreet, passive and active support of other governments, including Denmark, West Germany, Greece, Norway, Sweden, Turkey and others.

European operations not only involved USAFE, but also other USAF commands, the US Navy, US Army and CIA. Most programmes were highly compartmentalised; a considerable number were very short-term and often overlapped with each other. They frequently used the same, or very similar aircraft, operating from the same bases, using crews and missions often mounted against the same ‘targets’. These many operations were often interrelated and significantly impinged on Corridor and BCZ flights. The majority of the missions were launched from Wiesbaden and Rhein-Main (Frankfurt-am-Main International Airport) Air Bases. The Americans’ efforts to disguise many of these operations made them even more impenetrable to outside observers – as they were meant to be.

Early Post-Second World War Operations

In 1945, the Allies started a joint US–UK imagery collection programme over their respective occupation zones in Germany to update mapping, to help assess the needs of economic reconstruction and as a contingency against possible future military hostilities. Aware that post-war relations with the Soviets were going to be difficult, both were concerned that they lacked the necessary detailed targeting information about Europe that might be required in the event of a future global conflict.

In November 1945, the US 45 RS based at Fürth AB, near Nürnberg began to use its P-51D Mustangs and F-6Ks (the photographic reconnaissance version of the P-51 Mustang) to collect photographs over Germany. Details of these sorties are sparse, but by summer 1946 the squadron’s ‘Flight X’ had flown a small number of camera-equipped A-26 Invaders on occasional covert Corridor reconnaissance missions. Former USAF major Roger Rhodarmer, then a captain, and an experienced A-26 pilot, was sent to Germany to join 10 RG for photographic reconnaissance duties, of which he had no experience. Once there he was shown a modified A-26 that had a carefully concealed, forward-facing oblique K-18 camera with a 24in lens installed in the nose for Corridor flights. Most of the two units’ photographic reconnaissance tasks were not Corridor related, but involved flying between eighty and ninety hours a month on Project Birdseye, to photograph industrial and infrastructure ‘targets’ all over Europe at low level. The project was terminated in late 1946. In March 1947, 45 RS moved to Fürstenfeldbruck AB. It was not just the A-26s that flew such missions. In June 1946 a handful of camera-equipped RB-17s of 10 PCS based at Fürth AB started flying Project Casey Jones flights. This was a series of photo-survey sorties to update maps covering significant areas all over Europe.

In 1947, Detachment ‘A’ of 10 PCS took on an ELINT collection role, following serious incidents in the Austrian–Yugoslav border areas. On 9 August 1946 a USAAF C-47 Skytrain had departed Tulln Airfield in Austria bound for Rome, via Venice, on a routine scheduled courier flight. It encountered adverse weather and unwittingly strayed into Yugoslav airspace where it was intercepted and shot down by Yugoslavian Yak-3 fighters.

Fortunately all on board survived the subsequent crash-landing and were eventually released after being briefly interned. This sparked a series of sharp diplomatic exchanges between the US and Yugoslavian governments. Ten days later another C-47 was brought down in the same area by Yugoslav fighters. This time there were no survivors.

At HQ USAFE in Wiesbaden the question was – how could the Yugoslavs intercept the C-47s so effectively, especially in bad weather? The belief was that they possessed some form of radar fighter control capability, but hard evidence was lacking. To find the answer, two RB-17s were quickly fitted with intercept receivers and direction-finding antennae to equip them as ‘ferret’ or ELINT aircraft. On the first flight, along the Austrian–Yugoslav border, close to where the C-47s had been intercepted, transmissions from a familiar Second World War vintage German ‘Würzburg’ radar were detected, emanating from the site of a former German wartime radar school. The mission’s success encouraged USAFE to undertake further ‘ferret’ flights close to Soviet-occupied territory.