The backbone of RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain was made up of the single-engined single-seater Hawker Hurricane. In the 1930s this was the RAF’s first monoplane fighter, but in 1940 it was growing increasingly outdated in comparison to more recent aircraft.

Above all, the Hurricane was relatively slow. Top speed was 520 km/h at an altitude of 5,500 metres, which meant that it was about 35-40 km/h slower than the Bf 109. But the Hurricane’s larger rudder gave better stability during sharp manoeuvres, making it more manoeuvrable for less experienced pilots, and it could turn much more sharply than both the Bf 109 and Spitfire. In addition, the quite robust construction of the Hurricane made it able to sustain much more damage than both the Spitfire and the Bf 109. Another advantage – especially compared to the Spitfire and the Bf 109 E-1 – was its armament. Similarly to the Spitfire, the Hurricane was equipped with eight 7.7mm Browning .303 machine guns, but these were fitted closer together in the Hurricane, which gave a more concentrated firepower than that of the Spitfire, which had its four guns in each wing more spread out.

In the case of the Hurricane versus the Messerschmitt 109, most pilots agree – the latter was clearly better. Peter Brothers, who flew with Hurricane equipped 32 and 257 squadrons during the Battle of Britain, said: ‘As a pilot of a Hurricane you always had a certain respect, and even fear, for the Messerschmitt 109s. Firstly, they could dive faster. If the pilot of a Messerschmitt 109 saw you, he dived down and gave you a burst of fire, whizzed past, pulled the stick and climbed away very rapidly. You had no chance to follow him.’ According to ‘Al’ Deere, the Hurricane was, ‘although much more manoeuvrable than both the Spitfire and the Messerschmitt 109, pitifully slow and an extremely lazy climber.’

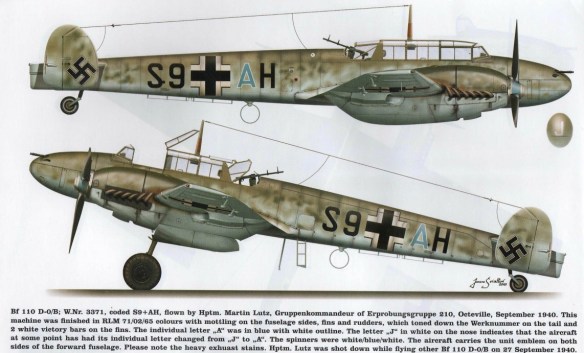

The second German fighter, the twin-engined two-seater Messerschmitt Bf 110, has been the subject of many myths and misconceptions. A fairly common notion is that it didn’t suffice as a day fighter, that it performed poorly in combat, and because of this had to be assigned with fighter escorts of Bf 109s. However, none of this stands up to closer scrutiny.

The Bf 110 was the result of the wargames conducted under Göring’s supervision in the winter of 1933/1934. These showed that the by then prevailing view that ‘the bombers will always get through’ – the notion that regardless of intercepting fighters and air defence a sufficient number of bombers always would get through to their assigned targets, where they were expected to cause enormous damage – was incorrect. In the summer of 1934, the leadership of the still secret Luftwaffe presented a study that suggested what at that time was quite revolutionary – a twin-engined fighter, heavily armed with automatic cannons as well as machine guns, to protect the bombers against enemy fighter interception. The idea was to dispatch these twin-engined fighter aircraft in advance, at a high altitude over the intended bombing target area, to clear the air of enemy fighters before the bombers arrived. Several of the more traditional thinking staff officers opposed this proposal, but Göring understood how far-sighted this was. Thus the fighter escort doctrine was born – the one that most air forces would adopt, although it would not be until ten years later that the Western Allies understood its benefits. Göring immediately in 1934 assigned the German aviation industry the task of constructing a new aircraft according to these principles. The new aircraft was designated ‘Zerstörer’ (destroyer). Göring eventually chose a design by the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, Bf 110.

It is commonly cited that the Bf 110 could not turn as tightly as the single-engined fighters. Good manoeuvrability was of course a significant factor in the fighter combats of the Second World War, but not to the same extent as in the First World War’s so-called ‘dogfights’ between slow biplanes and triplanes that circled in the same area. The fighter combats of the Second World War more often had the character of a kind of ‘Big Bang in miniature’: when both sides clashed, their flight formations dissolved explosively, with all the aircraft careering off at high speed in different directions. In such a melee, speed, climb and diving performances were at least as important as manoeuvrability. The tight turn is in itself a defensive feature – it makes it easier to avoid being hit by the fire of a pursuer. But in the offensive, the fighter pilots of the Second World War were able to use more powerful engines.

Hubert ‘Dizzy’ Allen, who flew a Spitfire with No. 66 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, wrote: ‘We were better at dogfighting than the fighter arm of the Luftwaffe, but only because both the Spitfire and Hurricane were more manoeuvrable than the Messerschmitt 109 and 110. In fact, dog-fighting ability was not all that important during the war. Fighter attacks were hit-and-run affairs on average. Either you dived with the sun behind you and caught him napping, or he did that to you.’

The Bf 110 was designed to strike down on enemy aircraft like hawks striking doves. With superiority in speed and altitude it could perform an attack effectively, without allowing itself to be drawn into turning combat – in exactly the same way as the Bf 109 pilots later learned to combat the much more manoeuvrable Soviet Polikarpov fighters on the Eastern Front. In these conditions, the Bf 110’s at that time unrivalled fire power often was decisive. In terms of flight speed, the Bf 110 models of 1940 were on pair with both the Bf 109 E and the Spitfire Mk I, and were significantly faster than the Hurricane. The Bf 110 was equipped with the same engines as the Bf 109, the DB 601 A, with fuel injection, and thus could outdive any British fighter. It also outclimbed the Hurricane and climbed almost as well as the Spitfire – unless it attacked the British in a quick dive from above; in doing so, the accumulated speed of the ‘110 made it impossible to follow in pursuit when it rapidly pulled up again.

In these kind of lightning attacks, the Bf 110’s armament at that time was unprecedented: two 20mm MG FF cannons and four 7.92 mm MG 17 machine guns concentrated in the nose. In addition, this aircraft had relatively ample room for ammunition. Its automatic cannons were loaded with 180 shells each, three times more than in a Messerschmitt 109, giving a total firing time of twenty seconds. The firepower of the Bf 110 was something that all RAF pilots soon learned to fear. Since the ‘110 was twin-seated, it was also equipped with a rear machine gun. This single, flexible 7.92mm MG 15 did not have any greater firepower, but this was often compensated by the extensive gunnery training of the radio operator who manned the machine gun.

The Messerschmitt Bf 110 was not only superior to the ‘109 regarding armament, but it also had a significantly larger operational range – which was a significant factor in the Luftwaffe operations over the British Isles. There was an important difference in principle between the two Messerschmitt fighters: as we have seen above, the Bf 110 had been developed according to Hermann Göring’s ‘Zerstörer Concept’, and thus was intended for the offensive. The original concept for the Bf 109, however, was defensive; it was meant as an Objektschutzflugzeug, an object cover aircraft, i.e., a short-range interceptor designed to patrol over for example an important industrial area to protect it against air strikes.

The results of the Bf 110’s operations during the Battle of Britain show that contrary to common perception it was at least as effective as the Bf 109 when it was used in free hunting – in other words according to the concept for which it was designed. Hans-Joachim Jabs, who as an Oberleutnant flew a Bf 110 with II./ZG 76 – the famous ‘Haifischgruppe’ – during the Battle of Britain, described his favourite method with the aircraft: ‘With a Messerschmitt 110 on free hunting you could strike down on the British and destroy them with the aircraft’s heavy armament. Then we could use the speed accumulated during the diving to climb to a higher altitude again. If we were attacked by British fighters when we had such a high speed, we could easily outclimb them. Then we could use our dive speed for a renewed attack to shoot down another one of them who was not careful enough.’

Mainly through this tactic, Jabs scored nineteen victories with his Bf 110 up until September 1940, and for this he was awarded with the Knight’s Cross. By that time, II./ZG 76 was the Luftwaffe’s most successful fighter Gruppe in terms of of victories.

Robert Stanford Tuck served as a Flight Lieutenant with 92 and 257 squadrons during the Battle of Britain and developed into one of the RAF’s first big fighter aces. He describes the Bf 110 as ‘an airplane that was very unpleasant to face, because of its quite heavy armament in the nose’. Tuck continues: ‘Rule number one was: Make sure you do not get a 110 on your tail. If that happened, you could be sure to get a whole lot of ammo over yourself, concentrated. In addition, [the Messerschmitt 110] had a rear gunner, and I had a feeling that their rear gunners were quite good at aiming and very determined. They continued to fire at you until the last moment, until your bullets had wounded them fatally.’

Neither did the Bf 110 have such a bad manoeuvrability as has often been claimed. Indeed, it could not make as tight turns as the Hurricane or the Spitfire, but in the hands of a skilled pilot it could turn almost as tight as a Bf 109 at high speed above medium flight altitude. Several combat reports by RAF pilots from the Battle of Britain testify to this. Eric Marrs, who flew a Spitfire with No. 152 Squadron, describes a dogfight with a Bf 110:

‘We circled around each other for a bit in tightening circles, each trying to get on the other’s tail, but my attention was soon drawn by another ‘110 … I milled around with him for a bit … I rolled on my back and pulled out of the melee and went home.’

Major Walter Grabmann, who commanded Bf 110-equipped ZG 76 during the Battle of Britain, flew mock combats with Bf 110s against captured British fighters on several occasions, and came to the following conclusions: ‘Concerning the performance of the Bf 110: I myself carried out very many comparison flights with the Bf 109, Bf 110 C against Bf 109 E. Speed equal, Bf 109 somewhat better in a climb, Bf 110 somewhat faster in a shallow dive. Dogfighting: 50:50. It was the same against the Spitfire.’

What mainly made the Bf 110 actually more suited for the special demands of the Battle of Britain than the Bf 109, was its large operating range. From bases in northern France the Bf 110 could reach all the way to Scotland – a longer distance than all German bomber types except the Ju 88. The Bf 109 on the other hand could at best reach to London’s northern outskirts, then the fuel in its small tanks began to run out, and the pilot had to hurry home. If the Bf 109s became involved in fighter combat, or if they were assigned to provide the bombers with close escort – which forced the pilots to orbit above and around the slow bomber – the fuel would run out of even earlier. German bomber formations were repeatedly dealt heavy losses over England because the Messerschmitt 109s had been short on fuel and had to leave the bombers, while there were too few Bf 110s. Of the Luftwaffe’s fighter planes in the summer of 1940, only about one-fifth consisted of Bf 110s and the rest were Bf 109s. (The ‘He 113’, frequently mentioned in the British combat reports from this period, was nothing but a German propaganda trick; ‘Heinkel 113’ never existed – in cases where such an aircraft was mentioned it was merely a case of confusion with Bf 109s.)

The RAF also had a couple of twin-engined fighters, but none of them could be compared with the Bf 110. The most common was the Bristol Blenheim. The Air Ministry’s decision to build a heavy fighter version of the Blenheim bomber soon proved to be a mistake. The Bristol Blenheim IF was slow – the top speed was in line with standard medium bomber, even lower than that of the Ju 88. How it compared with the Bf 110 was made clear by the Zerstörer fliers of I./ZG 1 on 10 May 1940, when they shot down five out of six Blenheims from 600 Squadron’s ‘B’ Flight without own losses. One consequence of this was that the Blenheim IF was shifted to mainly night fighter operations.

The other twin-engined British fighter was Westland Whirlwind – quite a small aeroplane (a length of only 9.83 metres, compared with the Bf 110’s 12.3 metres). With a top speed of 580 km/h at 4,500 metres’ altitude – more than 10 km/h faster than the Bf 109 at that height – and an armament of four automatic cannons in the nose, the Whirlwind might seem to have been a great fighter plane. But its disadvantage was its low speed at high altitudes – which would have been a great disadvantage if it had been deployed during the Battle of Britain. Deliveries of the Whirlwind began slowly during the Battle of Britain, and on 17 August 1940 only five aircraft were at hand. Fighter Command’s Dowding decided not to use the aircraft in combat throughout the Battle of Britain – probably a wise decision.

Another less common British fighter that was used in the Battle of Britain was something as unusual as a single-engined but twin-seated fighter with an armament consisting of four 7.7mm machine guns in an electric-powered dorsal turret – the Boulton Paul Defiant. This machine probably was better than its reputation. Indeed, because of the extra weight of the turret it was relatively slow – the top speed was 490 km/h at 5,200 metres’ altitude, whereas the Bf 110 reached 530 km/h and the Bf 109 550 km/h. However, the plane may be considered a ‘slugger’. With the right tactics – where the planes flew in a ‘Lufbery-circle’ – it could take control over a fairly large airspace where it was quite dangerous for any enemy aircraft. But even if the Defiant has received an undeservedly bad reputation because of erroneous tactics, it could not be compared with the two German fighters planes.