In 1918 the United States, still inexperienced in modern warfare, rushed to field an effective air arm for the European war, while struggling to establish an industry to support the new service and the logistics to transport supplies to the front. The optimistic predictions and expectations of 1917 yielded to the chastening realities of coordinating an effort to fulfill them in 1918.

At the front the U.S. Air Service command was riven with internal rivalries, which the May appointment of Brig. Gen. Mason M. Patrick as chief to replace Gen. Benjamin Foulois did not resolve. Only when Col. Billy Mitchell became the top American air combat commander, with considerable independence in establishing objectives despite the army’s ultimate control, did these tensions ease. Yet certain problems continued to plague the new arm. The command of fliers by nonfliers and the army’s ignorance—from division staff officers to troops of the line—regarding the air service and its work remained dilemmas.

Colonel Mitchell, as his mentor Trenchard, was determined to take the aerial offensive. June’s strategic bombing and independent air operations, the formation of the RAF’s Independent Force, and Trenchard’s refusal to acknowledge any superior—even Marshal Foch, Allied commander in chief—prompted the United states to switch from assisting the British campaign to supporting Foch’s coordinated plan. Meanwhile, Pershing’s chief of staff warned air service officers “against any idea of independence.” The American air war would be a tactical campaign.

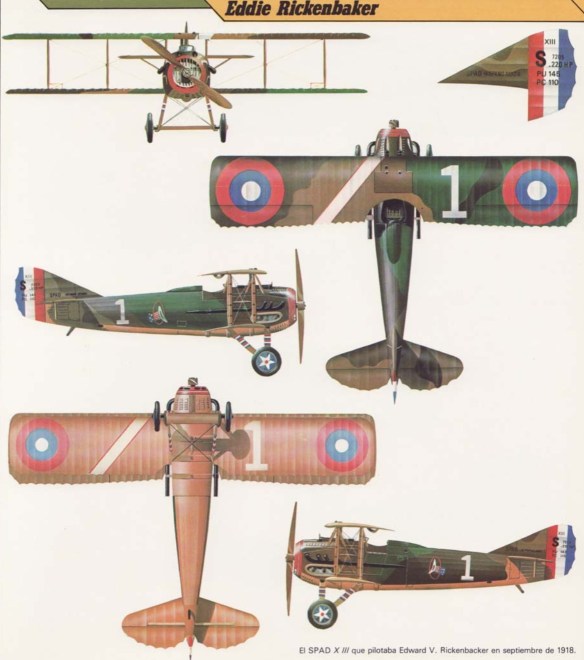

U.S. units saw action in the quiet sector around Toul in the spring. Ninety-three Lafayette Escadrille members transferred to the U.S. Air Service and 26 went to naval aviation. The escadrille’s aces took command of U.S. units. For example William Thaw was commanding the 103rd Squadron of mostly former escadrille fliers when it transferred into the U.S. Air Service in May. Raoul Lufbery, the escadrille’s ace, after a short stint flying a desk at the huge U.S. training base at Issoudun, returned to the air only to be shot down in flames in May by a German two-seater. Lufbery had shared his knowledge with Eddie Rickenbacker, a 27-year-old new pilot of the 94th Squadron and former race-car driver. Rickenbacker scored his first victory on 29 April and ultimately gained 26 victories to become the United States’ leading ace.

By the end of June, 13 squadrons were operating at the front—6 pursuit, 6 observation, and 1 bomber squadron—when they transferred to the fighting around Château-Thierry during the Aisne-Marne offensive in July. Over Château-Thierry U.S. pursuit pilots encountered for the first time large concentrations of Fokker D7s, which fought aggressively and tenaciously in teams and made attacks on German observation planes dangerous. The inexperienced pilots of the First Pursuit Group, mounted on France’s second-line fighter, the Nieuport 28, found that they could not yet compete with the D7. In their three-plane incursions over German lines, they were barely able to defend themselves, much less U.S. observation planes.

The first U.S. day-bomber units, flying Breguets, began operations in June attacking railroad yards. On 10 July six Breguets of the United States’ only bombing squadron, the 96th Squadron, got lost and were forced to land behind German lines. They compounded the disaster by failing to burn their aircraft, prompting the German message, “We thank you for the fine airplanes and equipment which you sent us, but what will we do with the Major?”

By fall circumstances had improved markedly. When the AEF First Army attacked the Saint-Mihiel salient on 12 to 16 September, Colonel Mitchell had under his direct command or on call 1,481 airplanes—701 pursuit, 366 observation, 323 day bombers, and 91 night bombers—the largest concentration of Allied air forces during the war, nearly half of which belonged to the United States. Despite poor weather conditions, this overwhelming mass retained aerial control as the fighters penetrated over German airfields and day bombers struck targets on the battlefield and in the rear. Saint-Mihiel marked the meteoric ascent of the 27th Squadron’s Arizona balloon-buster Frank Luke, who concentrating on observation ballons shot down 18 Germans in 17 days, but was downed by the Germans on 28 September as the Meuse-Argonne offensive began. In an unusual gesture for a downed pilot, Luke, rather than surrender, pulled his pistol to fight on the ground and was killed. His wingman and protector, Joseph Wehner, an ace in his own right, had fallen 10 days before.

American bomber crews, whether flying Breguets or DH4s, suffered severe losses during the offensive when operating in small formations of 3 to 6 airplanes but far fewer in larger tight formations. The United States’ use of virtually unprotected day bombers on raids 10 to 20 kilometers behind German lines—a French and British practice—resulted in such heavy losses that the U.S. Air Service resorted to bomber escorts in the Meuse-Argonne campaign. In that campaign from 26 September to the end of October, Mitchell pursued the same tactics as over Saint-Mihiel. He sent 100 aircraft-pursuit groups strafing over the lines, and staged his largest daytime raid on 9 October with 200 bombers and 100 fighters attacking German troop concentrations. Mitchell also further increased the size of his fighter patrols to counter German formations at the point of the U.S. attacks. The corps observation planes had the most difficult task—keeping pace with the infantry in contact patrols performed at tree-top level, often in fog and ground mist—in addition to their artillery observation tasks. Ultimately 18 observation squadrons would serve army or corps headquarters in what the army regarded as aviation’s most essential task.

Losses in the intensive fighting in the war’s last three months offset the influx of new units to the front, and many of these approximately 31 units were understrength. On 26 September the air arm had 646 airplanes; on 15 October it comprised 579; and at the Armistice it could muster 45 squadrons with only 457 serviceable planes, less than half the authorized program. Supply remained a problem throughout the war, and was particularly grave during the Meuse-Argonne campaign. At the end of October the three pursuit groups could assemble only a little over half their listed strength of 300 Spads.

The U.S. Air Service received 6,624 combat planes—4,879 from the French, 1,440 DH4s from the United States, 272 from the British, and 19 from the Italians. Of its French planes, 1,644 were Nieuports, 893 were Spad 13s, and 678 were Salmsons. At the war’s end some 80 percent of the air service’s planes were French made. The Spad 13, France’s first-line fighter, though not particularly maneuverable, was strong and the fastest fighter at the front. It was more difficult to keep in operation than the Nieuport 28 because the geared Hispano-Suiza 220-hp engine was more difficult to adjust and repair than the Nieuport’s 160-hp Gnome rotary. In the August Saint-Mihiel buildup, problems with the 220-hp Spads of the 22nd Squadron made concentration on combat difficult, and at Saint-Mihiel some pilots could fly only one mission a day because mechanics were able to keep only 65 percent of the planes serviceable.

U.S. squadrons judged the DH4 inferior to the Breguet for bombardment and the Salmson for observation. Similar average losses of Breguet, Salmson, and DH4 squadrons in the war’s final months were misleading, since squadrons in quieter sectors used the DH4. The Breguet was faster, its metal-tubing fuselage stronger than the DH4’s wood frame, and possessed better load and altitude capability. The sturdy Salmson 2A2 was overall the best observation craft. Although corps observation missions—especially infantry-contact patrol—suffered serious losses to enemy pursuit in the absence of fighter protection, on army observation missions above 15,000 feet the Salmson with its 260-hp radial could outrun the Pfalz, Albatros, and Fokker D7 and outclimb both the Pfalz and the Albatros.

There were numerous complaints about faulty materiel, particularly engine assembly and magnetos. The DH4 frame was too weak for the Liberty engine to run at full throttle without shaking the plane to bits. One U.S. engineer officer considered Liberty planes unprepared for service and often replaced their shock absorbers and wheels with Breguet parts. Beyond such construction flaws, the absence of self-sealing gas tanks offering some protection against fire in the DH4s did not help the morale of bomber crews. French plane tanks had asbestos-rubber coatings that automatically sealed bullet holes. The DH4’s nickname, “Flaming Coffin,” stemmed from its unprotected gas tanks and pressure-feed gas system. If a bullet punctured the gas tank, the pressure system forced fuel out of the unsealed hole over the airframe. A single incendiary bullet or spark made the plane a flaming funeral pyre for its crew.

Such potential fate did not deter American aircrews. Second Lt. W. J. Rogers, a DH4 observer of the 50th Aero Squadron, commented:

Aerial observation is neither a bed of roses nor the path to glory that the man on the ground imagines it to be. The wind behind a Liberty is terrific, and it taxes the strength of the strongest to fight it for three hours. If the ship is rolled and tossed about very much, . . . the occupants sometimes get sick . . .

But I like it. I’m sorry we had war, but since we did, I’m glad I was an aerial observer.

Aircrew members underwent training at home and in Europe. The Signal Corps adopted the Canadian method, establishing ground training units at eight universities that ultimately put more than 17,000 cadets through an 8- to 12-week course. Although the army increased its flying fields for primary training from 3 in 1917 to 27 by the war’s end, airplane and instructor shortages in the United States caused many aircrews to receive their primary and advanced training in Europe.

The most noted training grounds in France were the pursuit school at Issoudun and the bomber school at Clermont-Ferrand. The French fighter-training method emphasized individual tactics rather than teamwork and formation flying, although “gang” or “collective and cooperative” fighting, perhaps the “exact antithesis of the ‘sporting attitude,’” was most efficient and appropriate in 1918. The U.S. fliers did not fully appreciate the necessity for formation training until after the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, when they modified their instruction. Meanwhile, trainees and instructors in the bombardment school at Clermont-Ferrand suffered from dissatisfaction and poor morale. School commanders complained that pursuit aviation received excessive publicity, and that training for observation and bomber aviation was undervalued, neglected, and used as a threat for poor fighter-pilot trainees.

Casualties of U.S. Air Service personnel attached to all armies in Europe mounted steadily from four in March to 537 in October. Of the total 583 casualties, 235 were killed in action, 130 were wounded, 145 taken prisoner, 45 were killed in accidents, 25 were wounded, and 3 were interned. Accidents at the front and in flight training were as lethal for the American air arm as other air arms. The figures show that 681 flight personnel died in the air service, 508 (74.6 percent) of them in accidents (263 training in the United States, 203 in AEF training schools in Europe, and 42 at the front), 169 (24.8 percent) in combat, and 4 (.6 percent) from disease. In 1920 Lieutenant Colonel Rowntree of the Medical Reserve Corps concluded that “for every flier killed in combat three succumbed to accidents.” In addition, 72 were missing, 137 taken prisoner, 127 wounded, and 3 interned at the front. Of the 2,034 flight personnel—1,281 pilots and 753 observers—who reached the front, for every 100 trained fliers 24 had been killed; for every 100 pilots 33 had been killed; and for every 100 observers 4 had been killed. Pursuit training took the highest toll, followed by night bombing, day bombing, and then observation.

On 6 April 1917 the navy had 21 seaplanes in use, and on 14 October it had over 500 seaplanes at U.S. naval stations and 400 abroad. U.S. naval aviators flew Capronis in the northern bombing group at Calais-Dunkirk. However they received only 18 Capronis in July and August 1918 instead of the 140 promised, and the planes’ Fiat engines were so poorly built that they had to be completely reconstructed. The first Caproni with the superior Isotta-Fraschini engines arrived just after the Armistice. The group’s day bomber DH4s flew with RAF units. The naval operation remained small, and at the Armistice it had only 17 serviceable aircraft—6 Capronis, 12 DH4s, and 17 DH9s—instead of the 40 Capronis and 72 day bombers planned. By the war’s end naval aircraft would be based at 27 naval air stations from Ireland to Italy, and for their overwater operations they would rely increasingly on U.S.-made seaplanes—Curtiss boats with Liberty engines.

In the United States, the disarray in the aviation industry continued in 1918. By January the production program’s failures led President Wilson secretly to authorize sculptor and air enthusiast Gutzon Borglum to investigate the existence of an “aircraft Trust.” Borglum’s attacks forced the resignations of Col. Edward Deeds and Howard Coffin. By mid April aviation manufacturers, members of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs and particularly a president’s special committee investigating the industry recommended placing the aircraft program under a powerful civilian executive separate from the Signal Corps. Builders complained about the lack of definite orders; the Senate committee decried the delays in the provision of training aircraft, the “gravely disappointing” production of Liberty engines, and combat-plane production that was “a substantial failure and constitutes a most serious disappointment in our war preparations.” The committee majority believed that production needed to be removed from the Signal Corps entirely, although a minority insisted that the program was doing well given its difficult circumstances.

In May the president appointed Brig. Gen. William Kenly, Pershing’s former aviation chief, director of the Division of Military Aeronautics directly subordinate to the Secretary of War. President Wilson selected John D. Ryan, a director of the Anaconda Copper Company, to direct the army’s Bureau of Aircraft Production and chair the Aircraft Production Board. The two offices proceeded to operate independently, since Secretary of War Newton Baker was too overburdened to serve as liaison between Kenly and Ryan. On 22 August a report by a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs recommended establishing an independent air secretary with a seat in the cabinet over a department of aviation, as existed in both England and France. In August 1918 President Wilson placed Ryan in charge of aviation, appointing him a second assistant secretary of war and director of the U.S. Army’s air service, but Ryan then left on a six-week tour of Europe, and the war ended before the new arrangement took effect.

As the government struggled to correct matters, rumors spread. The 22 March New York World carried part of Gutzon Borglum’s report to the president, and Wilson referred the matter to the Justice Department. Charges of profiteering and conflict of interest led to an investigation of aircraft production by Charles Evans Hughes, Wilson’s opponent in the 1916 election and a former Supreme Court justice. The investigation, which was completed in October, yielded evidence of confusion and conflict of interest though none of corruption or conspiracy. The matter was dropped at the war’s end.

During this political turmoil, the U.S. aviation industry strove to develop and produce combat airplanes. DH4 production began to accelerate in May, when 153 were manufactured, and culminated in October with the production of 1,097. Only 67 had reached the battlefront by 1 July, but tests showing them to be structurally weak and defective forced a temporary suspension of contracts. In 1918 Liberty-engine production increased dramatically from 39 in January to 620 in May to 1,102 in June and finally to 3,878 in October. In July some aircraft plants were shut down or running below capacity.

The failure to manufacture foreign designs in the United States resulted from production problems. The government’s cancellation of Spad production at Curtiss in January necessitated providing large advances to prevent the firm’s collapse. In late April the Joint Army and Navy Technical Board recommended SE5 production at Curtiss, but the prototype, an SE5a with a 200-hp geared Hispano-Suiza, arrived with incomplete drawings that mixed the SE5a and the SE5 with a 180-hp Hispano-Suiza. Later, on 20 August, the official test of the U.S. SE5 revealed engine and radiator problems. When the order was canceled at the Armistice, Curtiss had produced only one SE5.

The 2,000 Bristol fighters ordered from Curtiss in January met a similar fate. Curtiss initially believed that the plane required extensive redesign and strengthening to contain the Liberty, but later abandoned these reservations. The first plane crashed in test on 7 May, then another crashed nose first on 7 June, killing the crew, as did a third in a 15 July test. The overpowered plane was deemed “unsafe, overloaded, and [of] no military value.” On 20 July the order was canceled. The United States would build no frontline fighters, only fighter trainers.

In February the Aircraft Production Board decided to produce both Handley Pages and Capronis and placed contracts in April with the Standard Aircraft Corporation in Elizabeth, New Jersey. By late June Army Chief of Staff Gen. Peyton C. March was studying the United States’ ability to produce the Handley Page four-engine giant V/1500. In late July the plant began to ship unassembled Handley Page 0/400 bombers without engines to England for assembly. It ultimately sent fewer than 100, none of which reached the front. Meanwhile, after much delay, misunderstanding, and trouble, the Caproni flew on 4 July and proved to be overpowered by the Liberty engines. In October the government decided that Capronis and Handley Pages were a stopgap measure until the manufacture of U.S. Martin bombers, a new design by Glenn L. Martin and Donald Douglas that would prove to be the world’s best light bomber in 1920. The Armistice, however, led to the cancellation of all Caproni and Handley Page orders.

Capt. Frank Briscoe, assigned to manage Caproni production, attributed the long delay and great expense to the serious problems of adjusting metric plans for skilled woodworkers to production by machine methods using U.S. measurements. He considered the greatest obstacle of all to be “the military method of handling industrial projects,” specifically the absence of a single authority to manage the project.

A report on U.S. aircraft production submitted on 22 August by a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs ascribed the disappointing results in aircraft production to the automobile manufacturers’ control of the program. Their lack of experience in aircraft production and the emphasis on the Liberty engine, which was thought capable of powering all aircraft types, were largely responsible for production delays. The committee rejected as reasons for delays the difficulty of measurement conversion and of securing sufficient engines, and accused the board of being mainly concerned with adapting planes to the Liberty engine, referring to the abortive attempts to adapt the engine to the Bristol fighter and the Spad. It condemned the organization under the Aircraft Production Board as unsystematic and inefficient, and believed that the board should have heeded the 1917 recommendations of Colonel Clark and Colonel Boiling to produce foreign planes and engines. The committee also suggested that the board should have adopted the Italian approach of selecting the best French types for production and then gradually moving to domestic designs. It judged that a substantial part of the $640 million appropriation had been wasted, citing the $6.5 million expended on the Bristol fighter and the over $6 million expended on 1,200 standard J-trainers that had to be condemned.

The navy’s seaplane procurement was highlighted not just by Curtiss’s success but also by that of the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, which had begun deliveries in April. The first Naval Aircraft Factory plane flew in March, only 228 days after the factory’s ground-breaking ceremonies. By the war’s end the factory employed 3,750 workers, a quarter of them women, and by 31 December 1918 it had built 183 twin-engine flying boats, the last 33 of them Felixstowe F5Ls, the final version of the British boat powered by a Liberty engine. A critical difference between the circumstances of naval and military procurement was the navy’s foundation of the Curtiss designs, which compared favorably to those abroad and were probably the United States’s true aircraft production success story. The military had no domestic landplane design of comparable standing.