Iran’s introduction to modern war came in a fashion startlingly similar to the collapse of the Iraqi military in May 1941. Two months after the British had destroyed the Iraqi Army, British forces from the west and south and Soviet forces from the north annihilated the Iranian Army and overthrew Reza Shah Pahlavi’s pro-German government. They placed his son, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, on the throne. Despite numerous internal challenges to Pahlavi rule by various political, ethnic, and religious movements, the young Shah managed, with significant assistance from the United States and United Kingdom, to retain power. Using the immense wealth conferred on his country by the oil boom of the 1970s, the Shah built the Iranian military into a formidable force, one equipped with the most modern American and Western weapons.

An Iraqi military assessment from July 1979 noted that in addition to reflecting “the American military ideology and tactics related to limited and modern wars, such as [the] Vietnam War, Indian/Pakistani War, and Arab/Israeli Wars,” the Iranian military reflected the Shah’s “aggressive, expansionist ambitions.” This assessment cited the development of new commands (airborne command in Shiraz, naval commands focused on the gulf and sea of Oman, three “field corps” in Tehran, Shiraz, and Khorramshahr), an increase in infantry formations, the addition of twenty-four infantry regiments during the preceding decade, contracting for modern naval and air force weapons, and the steady improvement of military-related infrastructure. Moreover, Iranian air, sea, and ground units consistently trained to higher standards than those of the Iraqis, at least before Khomeini’s revolution. Better equipped, better trained, and more numerous, the Iranian military had been a major reason why the Iraqis, to Saddam’s considerable shame, had buckled under direct and indirect Iranian pressure in 1975 and signed to the Algiers Agreement.

US policy toward Iran was changing throughout the 1970s, but in the end it was all about security. For the United States, Iran was a client state whose anti-Communist stance and willingness to support US interests in the region – notably Israel and the free flow of oil – represented an emerging pillar, along with Saudi Arabia, of stability in the Persian Gulf. The explosion of oil wealth along with the Nixon Administration’s policy to sell “Iran those weapons it requested” dominated the large and diverse economic and cultural relationships between Washington and Tehran.

By 1978, the year before Khomeini’s revolution, Iran counted 447 aircraft in its air force, fully a third more than those possessed by the Iraqis. Among those aircraft were F-14s, F-4s, and F-5s – all weapons systems superior to the Soviet equipment in the Iraqi arsenal. In addition to the aircraft, American air-to-air missiles and electronic warfare equipment gave the Shah’s Eagles a distinct technological advantage over Saddam’s Falcons. In the wake of the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, the Shah increasingly emphasized the quality of training and made full use of his relationship with the United States to train Iranian aircrews to a standard far exceeding Iraqi pilots. By 1977, despite the Shah’s penchant for “leadership by distrust,” whereby officers were played against each other and joint service planning was all but forbidden, Iran’s 100,000-man air force was the most powerful in the Gulf.

However, the arrival of the religious revolutionaries in Tehran led to defections and major purges primarily at the top ranks, but occasionally down to the pilot level. Once the war broke out, the regime brought back a number of pilots from prison or civilian life to serve in frontline squadrons against the Iraqis. Nevertheless, the aircraft and pilots proved wasting assets, because soured US–Iranian relations ensured that Khomeini’s air force received few American-made spare parts, supplies, and equipment, and no more Iranian pilots would be trained in the United States. Consequently, according to Iraqi intelligence, less than half of Iran’s aircraft were flyable, and in some squadrons the maintenance picture was even bleaker. An Iraqi intelligence report from July 1980 indicated that only five F-14s of Isfahan’s two squadrons of Tomcats (approximately forty aircraft) were serviceable. Moreover, there were fewer pilots to fly them, because many had been arrested on suspicion of plotting a coup.

The Iranian Navy fared better than the other services in the purges, and despite logistic problems, maintained its pre-1979 naval superiority over much of the Gulf in the early years of the conflict. The Shah had equipped it lavishly. In 1978, the navy possessed three guided missile destroyers, four frigates, and an assortment of lesser vessels to oppose Iraq’s nine fast missile boats. An Iraqi assessment from July 1980 described the navy in the post-Shah period this way: “The Iranian naval force [has] suffered the least from the political events for two reasons. It [has] stayed away from participating in attacking the forces opposing the Shah, and Ahmad Madani, who was appointed as its commander, persisted in protecting its capabilities.” Out of a force of more than 28,000 naval personnel, the Iraqis estimated only 3,000–4,000 desertions after the Shah’s fall. Overall, the report noted, “fighting qualification can be evaluated average/below average.”

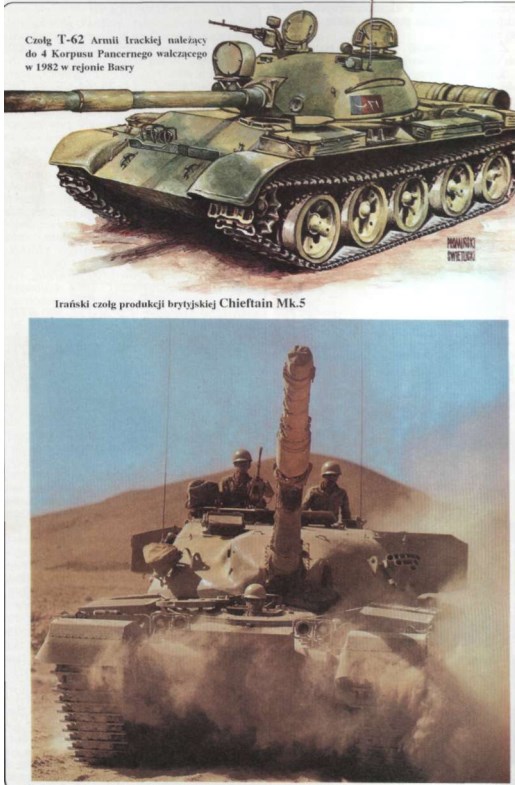

The Shah had equipped his ground forces as generously as he had his navy and air force. In 1978, before Khomeini’s return, the Iranian Army numbered 285,000 soldiers against the 190,000 soldiers in the Iraqi Army. Relying on American and British suppliers, the Shah had amassed 1,800 tanks by 1978, which served as the backbone for three armored divisions, three infantry divisions, and four independent brigades (one armored, one infantry, one airborne, and one special forces).

Many of Iran’s tanks were older model American M-47s and M-60s, but the Iranians also possessed 760 of the newer British Chieftains. The army also deployed 600 of the most modern American and British helicopters. Moreover, at the time of the Shah’s fall, the Iranians had a further 1,450 Chieftains on order and were cooperating with funding in the development of the British Challenger tank and its Chobham composite armor. In addition to Western-style training by the British and Americans, the Iranian Army gained some operational and tactical experience during deployments to Oman in the early 1970s, where it helped suppress Communist rebels. Despite these qualitative advantages, the Shah’s army suffered the same fate as most others under totalitarian systems.

The Shah controlled every aspect of military life including promotions above the rank of major. As one study noted, the Shah’s ground forces, “although militarily proficient, were lacking any independent decision making capability, sense of identity, or ability to coordinate among themselves.” Moreover, the fact that the Iranians in comparison to the Iraqis had a far greater distance to deploy and sustain a fight from their cantonment areas in the central and northern portions of their country considerably made up for the difference in numbers. In terms of divisions and corps and major ground weapons systems, the two countries were nearly equal in the last years of the Shah’s rule.

All of that radically changed in the aftermath of Khomeini’s return to Tehran. The Islamic Revolution reversed the strategic balance, at least for the short term. The reversal was a result not just of the revolutionary chaos but part of a naïve and ill-timed plan by the revolutionaries to disarm large parts of an armed force which they felt possessed many “excessively and unnecessarily sophisticated weapons.” On 6 March 1979, the new government announced that from then forward, Iran would no longer serve as “policeman of the Persian Gulf”; it began converting naval facilities into fishing harbors, canceling military hardware contracts, and expelling Western trainers. An Iraqi military assessment of the Iranian Army shortly after the revolution noted that it was “generally inefficient” and operating at only 50 percent of its prior effectiveness. The report attributed the decline in “discipline and moral” to:

1) Units being “driven by committees” made up of clergy. This “had a bad effect” on the psychological state of commanders … 2) Army personnel feel they could be “retired or expelled” from the service at any time. 3) Deployments in the Kurdish region “under undesirable conditions.” 4) No training (with the exception of the 16th Armored Division). 5) Lack of maintenance and spare parts.

Reports from Iraq’s military attaché in Tehran added to the assessment that the Iranian military was in a state of collapse. On the occasion of the Army Day parade in April 1979, he noted, “The morale [of] the Iranian soldiers is still low. Comparing uniforms, marching, and general structure of the former Iranian soldier and officer with that of the current ones, you will find a huge gap, whereby the paraded soldiers are marching with uniforms that resemble that of prisoners and most of them are antiques.” Moreover, “as for the march, it resembled that of a prisoners’ march after combat.” The attaché also reported that despite the announcement that ten regiments would pass in review, he counted only five. In conclusion, he noted that “we did not observe any high military ranks in the parade, but the rank was limited to major and lower.”