Not until April 1915 did OHL inform OAK in Vienna how it planned to use Mackensen’s 11th Army, and only then because it required Conrad to transfer two corps of his 4th Army to Mackensen’s command. Conrad again protested that the area of intended operations was on the front of which he was commander-in-chief, but had to accept this partial usurpation of his authority, since it seemed the only way to force Brusilov’s retreat from the Carpathian passes, where he was little more than 100 miles from Budapest, twin capital of the dual monarchy.

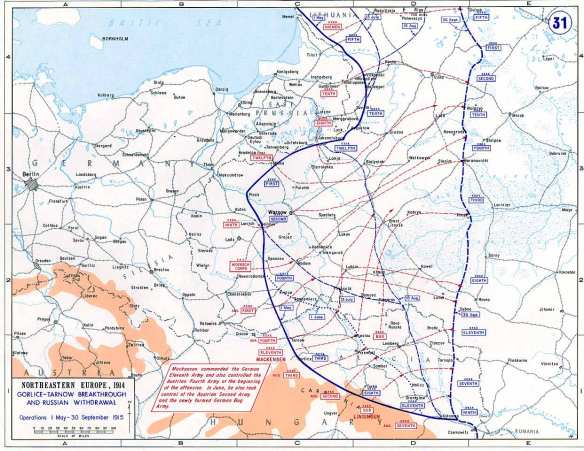

On paper, the Central Powers now had a coordinated strategy from the Baltic coast right down to the Romanian frontier. In East Prussia, Hindenburg’s forces consisted of the new 10th Army, 8th Army under von Below and 9th Army facing Warsaw. South of the salient, Austro-Hungarian forces were, from north to south, 2nd, 1st, 4th and 3rd armies. Russian forces holding the line were 10th Army in the north on the East Prussian border, 1st and 2nd armies defending Warsaw in the salient and the new 12th Army to the north-east of Warsaw. South of the salient, facing the Austro-Hungarians, were 5th, 4th, 9th, 3rd, 8th and 11th armies.

On 2 May Mackensen’s artillery loosed a devastating 4-hour barrage on a 35-mile stretch of the lines of Russian 3rd Army. He had tried to break through west of the River Narev in February and March, and was determined not to fail again. Mackensen had just over ten divisions in the line and another in reserve against the seven divisions of Russian 1st and 12th armies. He had 1,000 guns on this small front, with 400,000 rounds of shell, all coordinated by General Bruchmüller, the artillery expert, facing 377 guns with only forty rounds apiece. Immediately following the barrage, German infantry moved in, ready to tackle Russian survivors emerging from dugout shelters, but found instead almost all the men in the badly constructed front line, as well as the reserves, who had been held too far forward, lying dead because they had been cut to pieces in their trenches by shrapnel bursts and literally vaporised by high explosive (HE). It was about this time that the enormous numbers of casualties on the Russian fronts led to burials in ‘brothers’ graves’, where dozens and sometimes hundreds of men were buried in the same mass grave without discrimination of nationality, race or religion.

For the reality of what lies behind the bland body counts we have an eye-witness account. For those not killed outright and lucky enough to be brought to a letuchka, or mobile surgical unit, everyday nursing was in the hands of the krestovaye sestry – Red Cross sisters. A few of these women who braved all the discomforts and dangers of working close to the front lines were English. Florence Farmborough was a 27-year-old governess employed by a surgeon in Moscow, who had volunteered and been given a few weeks’ training in a hospital before spending a whole month in trains to reach the south-western front. Fortunately, she kept a diary, writing down events whenever she had time. With the general insufficiency of field hospitals, delay in treating even a small wound often meant death from infection. So the letuchki worked very close to the lines, moving frequently to keep up with advances and retreats. Florence’s first base was in a well-built house with several pleasant, airy rooms, where the nurses’ first task was to scrub every surface clean and paint or whitewash the walls. An operating theatre was set up and a pharmacy stocked with medicines and surgical material. They were told not to think they would be there long: the stay might be six months or six hours, depending on the movement of the front. Not knowing exactly what to expect, she took some solace in the scenery of the undulating Carpathian foothills.

Mackensen pressed on with the German 11th Army in the centre, flanked by Austrian 3rd and 4th armies, demolishing any sustained Russian resistance with more massive artillery bombardments. Conventionally, Russian units north and south of the CP advance should have attacked the flanks, but Stavka was afraid of Brusilov’s 8th Army being too exposed on the south-western front and ordered a general withdrawal to straighten the line, in the absence of sufficient heavy artillery – and especially sufficient stocks of shell – to even slow down the CP advance. Casualties rapidly mounted to the million mark, with reinforcements arriving and being thrown into battle after only two or three weeks’ training.

Three days after Florence’s arrival on this front, there was a sense of foreboding in her entry for 28 April, which recorded the arrival of a first batch of fifty wounded men, whose wounds had to be dressed before they were sent on to Yaslo. Against the booming of cannon fire, the soldiers voiced their dismay that German troops and heavy artillery had been sent to this section of the Front. ‘We are not afraid of the Austrians,’ they said, ‘but the German soldiers are quite different.’

Two days later, the new nurse of Letuchka No. 2 was shocked by a colossal influx of seriously wounded men after Russian 3rd Army was cut to pieces and 61st Division – to which the letuchka was attached – lost many thousands of men. The reality of a combat nurse’s exhausting life had sunk in:

We were called from our beds before dawn on Saturday 1 May. The Germans had launched their offensive. Explosion after explosion rent the air. Shells and shrapnel fell all around. Our house shook to its very foundations. Death was very busy, his hands full of victims. Then the victims started to arrive until we were overwhelmed by their numbers. They came in their hundreds from all directions, some able to walk, others dragging themselves along the ground. We worked day and night. The thunder of the guns never ceased. Soon shells were exploding all around our unit. The stream of wounded was endless. We dressed their severe wounds where they lay on the open ground, first alleviating their pain by injections. On Sunday the terrible word retreat was heard. In that one word lies all the agony of the last few days. The first-line troops came into sight: a long procession of dirt-bespattered, weary, desperate men. Orders: we were to start without delay, leaving behind all the wounded and the unit’s equipment! ‘Skoro, skoro! Quickly! The Germans are outside the town!’

Again and again, the surgeon, orderlies and nurses of Letuchka No. 2 fled eastwards out of towns and villages as the German spearheads entered them from the west. The arrival of a Cossack despatch-rider on his mud-flecked pony meant packing up the instruments and tents, always to head further east. Sleep-deprived, the nurses nodded off to get whatever rest they could in the jolting horse-drawn carts bumping over unmade roads. This was the Great Retreat of 1915.

In April 1915 Hindenburg also continued his push on the northern front into Russian-occupied Lithuania and Courland, relieving Königsberg and capturing the Russian naval base of Libau (modern Liepaja) on the Baltic coast in early May. On 2 May Mackensen’s now very mixed armies opened an attack from the line of the Vistula River, all the way south to the Carpathian Mountains. Preceded by an enormous barrage, it was a huge success, with Russian 3rd Army suffering severe losses. The advance continued with the capture of the ruined fortress of Przemyśl – which could not be defended because of all the damage caused during the Russian siege and the demolitions carried out by the Austrian garrison before surrendering in March. Less than three weeks later, Lemberg was also recaptured. The joint German-Austrian attack continued its momentum, driving the Russians back to the River San just over a week after that. By the end of the month, the front had shifted 100 miles to the east.

By 15 June Letuchka No. 2 had moved so many times as the front collapsed that it was back inside Russia, but the retreat was not over yet. Asleep on their feet, the nursing sisters collected up all the equipment and re-packed again and again as the temporary haven of care for the suffering where they had worked the previous day fell into the hands of the enemy. Bumping along the bad roads in unsprung carts, two of the nurses were ill – partly, Florence thought, from the sustained anxiety. Trying at night to sleep on a carpet of pine needles in the forest, she heard the nurse lying beside her crying quietly. When dawn came, they merged again into the stream of humans and animals, all moving eastwards. Entire herds of cattle were being driven by their owners with droves of sheep and pigs. And always behind them black clouds of smoke rose into the sky as all the peasants’ hayricks and barns full of straw were fired, to deny them to the enemy. She wrote:

It was said that the Cossacks had received orders to force all the inhabitants to leave their homes so they could not act as spies. In order that the enemy should encounter widespread devastation, the homesteads were set on fire and crops destroyed. The peasants were heart-rending. They took what they could with them but before long the animals’ strength gave out and we would see panting, dying creatures by the roadside, unable to go any farther. One woman, with a sleeping infant in her arms, was bowed almost double by a large wicker basket containing poultry, which was strapped to her back. Sometimes a cart had broken down and the family, bewildered and frightened, chose to remain with their precious possessions, until they too were driven onwards by the threatening knout of the Cossack or the more terrifying prospect of the proximity of the enemy.

Near Lublin in the salient 5,000 Cossack cavalry and Russian artillery wiped out two crack Austrian cavalry regiments, mostly killed in medieval manner by sabre or lance. Knox described one Austrian officer taken prisoner after having the whole of his lower jaw carried away on the point of a lance. Joseph Bumby described his capture like this:

I was left alone in front of the Russian trenches with six dead men on my left and the forest on my right. The Russians were 200 paces behind me when I was shot in the neck. In the evening when the firing died down, some Russian soldiers came close and called out to me. One escorted me to a house in the village of Něgartova where they gave me bread, tea and cigarettes, but they stole my gloves and some canned goods I had. Then they gave me some straw to sleep on.

One always recalls the first night in captivity, after which it all becomes a blur.

After General Alexander von Linsingen recaptured Strij with the Galician oilfields, which were 60 per cent British-owned, a cartel of businessmen in Berlin pre-echoed Hitler’s plan to enslave the populations of Russia, Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic states. The southern end of the Russian lines was now floating unanchored and Mackensen continued pressing his advantage for four months with the tsarist forces retreating all along the Russian fronts – which ran from Latvia in the north, looped around Warsaw and, with most of Galicia back in Austrian hands, continued south to the Romanian border.

On 7 July Russian forces took thousands of POWs on the northern front and pressed on to take the key fortresses at Königsberg and Allenstein before being driven back. Florence Farmborough’s mobile surgical unit was then attached to 5th Caucasian Infantry Corps. Her diary records that, of 25,000 men, only 2,000 were left. But the major defeat of that terrible midsummer was due to a joint German and Austrian push towards Warsaw. Although Stavka managed to extricate three armies from encirclement, once the loss of the Polish salient became inevitable, an evacuation of all civilians was ordered, with the destruction of all homes, food and animals in the scorched-earth policy used against Napoleon. Knox recorded the start of the Third Battle for Warsaw on 13 July, of which the first warning came when human intelligence indicated that the frontier railway stations at Willenberg, Soldau and Neidenburg were being enlarged to handle more traffic. After a feint along the River Vistula, the Germans opened up a hurricane barrage on 12 July, which showed that they had no shortage of shells on this occasion. The weather had been dry and roads were at their best, so one corps of Russian 1st Army had to counter forty-two large-calibre enemy guns with only two of its own, with the result that an entire Siberian division was virtually wiped out amid widespread panic. The infantry attack came in on 13 July, when the Russian troops withdrew from the front line without pausing to defend a second defensive line that had been prepared on the line Przasnysz–Tsyekhanov–Plonsk–Chervinsk. The majority of Russian conscripts being of peasant origin, when a scorched-earth policy was ordered in retreats, they routinely drove off livestock and looted other possessions from civilians, which slowed down their movement, with the result during this retreat the enemy cavalry caught up and broke through in the centre of the line, attacking the slow-moving and vulnerable transport columns. The term ‘scorched earth’ requires clarification. It seems that poor peasants lost everything, as did the Jews. But noble estates belonging to rich Polish landowners who had connections with German, Austrian and Russian high commands, could ‘arrange’ for their lands and property to be left intact.

On 16 July the fortified line Makov–Naselsk–Novo Georgievsk was reached, where Russian 4th Corps was sent immediately into combat as they stepped off the trains from Warsaw. Even this desperate measure was too little, too late. On the night of 18 July the retreat continued to the River Narev. After four German divisions forced a bridgehead on the right bank, it was decided to evacuate Warsaw. By this time, Russian 2nd Army had only a single corps remaining on the left bank, 4 miles outside the city. On the night of 4 August this too retreated to the right bank, after which the Vistula bridges were blown at 0300hrs on 5 August. The German scouts reached the left bank at 6 a.m.

By the time Warsaw fell to Mackensen that day, Russian losses in the war totalled 1.4 million casualties and nearly a million officers and men taken prisoner. The ‘black summer’ continued, but the German advance – in places up to 125 miles from the nearest railhead – was fraught with problems, corps commanders complaining that fodder for horses was impossible to obtain in sufficient quantity as they drove through primeval forest and hit the Pripyat marshes where, ironically, there was no drinking water for men or horses until it had been boiled.

There was already trouble brewing in the subject nations on both sides. A Czech independence faction wanted to use the war to break away from Austrian domination. The Slovaks wanted independence from Hungary. If not the Tsar, at least the Russian government was aware that the Finns, Poles, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, as well as the Caucasian nations subdued in the nineteenth century, were all waiting for the right moment to escape from Russian hegemony. In a feeble attempt to purchase the loyalty of the vassal races, the tsarist government promised reforms – which stopped short of independence – to Poles and Finns, to the Slavs of Galicia and to the Jews, although Nicholas was a strident anti-Semite.

Morale in some Russian units was still good although losses already totalled 3.8 million killed, wounded and taken prisoner. Even these figures are to some extent conjectural. General Hindenburg wrote:

In the Great War ledger the page on which the Russian losses were written had been torn out. No one knows the figure. 5 millions or 8 millions? We too have no idea. All we know is that sometimes in our battles with the Russians we had to remove the mounds of enemy corpses in order to get a clear field of fire against fresh assaulting waves.

On the day following the surrender of Warsaw, Colonel Knox lunched about 1,000yd from the firing line with the commander of the elite Preobrazhenskii Guards Regiment, founded by Peter the Great. They ate from a camp table covered with a clean white cloth and all the officers seemed in excellent spirits. When Knox asked about strategy, one of them joked: ‘We will retire to the Urals. When we get there, the enemy’s pursuing army have dwindled to a single German and a single Austrian. The Austrian will, according to custom, give himself up as a prisoner, and we will kill the German.’ There was laughter all round.

In another light-hearted moment Knox recorded two Jews discussing the progress of the war in a market. When one said, ‘Our side will win,’ and the other agreed, a Pole standing nearby asked which side was ‘ours’. Both the Jews said: ‘Why, the side that will win.’

What was the truth of the Russian belief that Slavs in Austro-Hungarian uniform would willingly surrender at the first opportunity? Firstly, as Bolshevik commissars were to do with fellow Russians a few years later, the officers and senior NCOs of Conrad’s predominantly Slavic units were ordered to shoot any men preparing to give up without a fight – as did also British and French NCOs and military police on the Western Front. Secondly, unless all the men in a particular group were agreed about surrender, there was always the possibility of an informer giving away the plan. Ferdinand Filacek was a Czech metal-worker from Litomysl who was called up, aged 18, in August 1914. Arriving at the front in mid-November, he was taken prisoner near Novy Sad on 5 December. It is true that he was temporarily out of danger, but the next year was spent in three different POW camps at Kainsk, Novo-Nikolajevsk and Semipalatinsk (modern Semeï in Kazakhstan) a sparsely inhabited area 2,000 miles east of Moscow, where the Soviet Union would explode hundreds of nuclear devices during the Cold War.