This is a German class 52 Kriegslok built in Vienna in 1943 and regauged to Russian 5ft gauge.

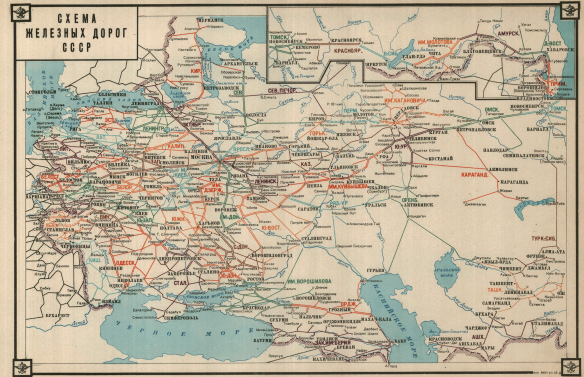

Soviet Railways1941

The middle group, aimed at Moscow and led by Field Marshal von Bock, was by far the strongest force. While initially its supply difficulties were the least pronounced of the three army groups because it straddled the main Warsaw-Moscow railway that remained undamaged, they were to play a crucial role in the army’s failure to reach Moscow. Indeed, the progress of the central army group was initially even more impressive than that of its counterpart to the north. The strategy was to create a series of pincer movements with Smolensk, about halfway to Moscow, as the target for the first stage of operations, but the usual difficulties of roads being blocked by streams of infantry and of insufficient railway capacity soon became apparent. There was a shortage of petrol exacerbated by the higher consumption of lorries on the atrocious roads and of spares, especially tyres, whereas on the railways there were the customary bottlenecks at the gauge changeover points. However, by and large there was reasonable progress until the Germans attempted to build up a supply base for the final attack on Moscow. Then it became clear that there was insufficient capacity to launch the assault on the Russian capital. Bock needed thirty trains per day to build up stocks whereas, at best, he was getting eighteen. Just as in the north, Hitler then changed the game plan, diverting resources – a tank unit, Panzergruppe 3 – to the south, along with 5,000 tons of lorry capacity, to ensure that Kiev could be taken. It was a terrible mistake. While Ukraine was important in terms of resources – wheat, coal and oil – Moscow was the centre of the nation’s communications and had the Germans been able to block it off, the Russians would no longer have been able to use the rail lines to transport troops between the north and south.

With the help of the extra panzers, Kiev soon fell but then another mistake resulted in the move eastwards being undertaken too hastily. Already the south group, which had been charged with taking Kiev and then crossing the Dnieper to capture the coalfields of Donetz and invading the Crimea, had been beset by wet weather that knocked out half its motor transport. Progress was also slowed by fiercer resistance from Russian partisans than faced by the other two groups. Once Kiev had been encircled, the eastward move resumed on 1 October but it was greatly hampered by the destruction of the bridges over the Dnieper, which forced supplies to be shipped across the river. The Germans took over sections of the Russian railways but they were in a poor state and during October barely a quarter of scheduled trains arrived at the two easternmost railheads. Chaos on the Polish railways further back on the line of communication added to the supply difficulties. Therefore, the decision to resume the offensive proved premature as, without any effective railway support, there was no hope of reaching the Donetz Basin with its mineral riches before winter set in. Although the Germans captured Rostov in late November, their supply lines were overextended and they subsequently lost the town, the first time the German advance had been successfully repelled.

The attack by the centre group on Moscow finally began on 2 October after the Panzer division returned from Kiev, but it was too little, too late. One unit reached the suburbs, but the Germans’ strength fell far short of the numbers needed to take the capital. There was a final hopeless attack on 1 December, which had no chance of success because of the lack of resources. The Red Army, which had the advantage of ski troops, counter-attacked, pushing the Germans back sixty miles by January, not only removing the immediate threat to their capital but, even more importantly in terms of morale, achieving their first large-scale success over the invading forces.

By the winter, therefore, all three prongs of the German advance were at a standstill far short of their objectives, and with little likelihood of achieving them. The Germans had to adapt to a war of attrition, for which they were not prepared, and which ultimately would be their undoing. As van Creveld concludes, ‘the German invasion of the Soviet Union was the largest military operation of all time, and the logistic problems involved of an order of magnitude that staggers the imagination’. Yet, although the means at the disposal of the Wehrmacht were modest, the Germans came closer to their aims than might have been expected, which van Creveld attributes ‘less to the excellence of the preparations than to the determination of troops and commanders to give their all’, making do with whatever means were made available to them. Indeed, during the initial phase of the attack, the supply shortages were greatly alleviated by the armies living off the land in the traditional manner, but once the frost set in, the conditions not only made transportation more difficult but the required level of supplies increased greatly. The most notorious failing was the lack of provision for winter coats and other cold-weather equipment for the troops advancing on Moscow, which resulted in thousands of men, fighting in their summer gear, freezing to death in the cold. There is much debate among historians as to whether this equipment was available or not, but van Creveld is convinced this is irrelevant because there were no means to deliver it: ‘The railroads, hopelessly inadequate to prepare the offensive on Moscow and to sustain it after it had started, were in no state to tackle the additional task of bringing up winter equipment.’

Ultimately, the Russian invasion was a step too far for the Germans, who even with everything in their favour and better preparation would probably not have succeeded simply because of the size of the task – the territory to be captured was some twenty times the size of the area conquered in western Europe and yet the German army deployed only 10 per cent more men and 30 per cent more tanks. Hitler’s dithering and his changes in strategy, and the dogged resistance of the Russians, often using guerrilla tactics, undermined the advance further and made failure inevitable, but supply delays played a vital, if not decisive, role. The German supply lines were simply extended beyond their natural limit, as the optimism of the HQ generals who had prepared the assault came up against the reality of the Russian steppe. The effect of the logistical shortfalls was not just practical but extended to the morale of the troops. Arguments between different sections of the military over the need for transport led the Luftwaffe to protect their supply trains with machine-gun-toting guards ready to fire not at Russian partisans but at German troops keen to get hold of their equipment.

Throughout the campaign, the Red Army troops retained the advantages of fighting on their own territory, which had proved crucial to all defending armies since the start of the railway age. Cleverly, rather than building up huge supply dumps that risked being captured by the enemy, the Russian Army supplied its troops directly from trains at railway stations, a task which required a level of flexibility and operational experience of the particular lines that would never have been available to an invading force. The Russians had, too, ensured that they retained most of their rolling stock by transporting it eastwards in anticipation of the German attack, with the result that the railways still in their control enjoyed a surfeit of locomotives and wagons. According to Westwood, ‘by 1943, the Russian railway mileage had decreased by forty per cent, but the locomotive stock by only fifteen per cent’.

Stalin, unlike Hitler, had long recognized the value of the railways and thanks to an extensive programme of investment in the interwar period the Russian system was in a much better state than at the onset of the previous war. While Hitler had been counting on the Russian system breaking down under the strain of retreating troops, it held up remarkably well. Indeed, the smooth running of the Russian railways was instrumental in allowing the rapid wholesale transfer of much of the nation’s industry during the early days of the war from threatened western areas to the remote east, an evacuation conducted so efficiently that even frequent bombardment was unable to disrupt it. At times traffic was so great that signalling systems were ignored and trains simply followed one another down the track almost nose to tail.

Russian railwaymen were effectively conscripted as martial law was imposed on the railway system and those who failed in their jobs were liable to find themselves in front of a firing squad – but then so was anyone else. Later in the war, however, Stalin, grateful for the railway workers’ efforts, created a series of special medals for railway workers, including one for ‘Distinguished Railway Clerk’, presumably for issuing tickets to war widows while under fire. The Russians laid a staggering 4,500 miles of new track during the war, including a section of line that supplied the defenders at Stalingrad. The railways were crucial, too, to the defence of both Leningrad and Moscow. When all the railway lines to Leningrad were cut off by September 1941 – the Finns blocked communications from the north as they were fighting with the Germans – the ‘death’ road across the frozen Lake Ladoga, so called because of the dangers of using it, became the last lifeline to the beleaguered city and was supplied from trains. Towards the end of the siege a railway was built across the ice, like on Lake Baikal in the Russo-Japanese War, but since the territory around the south of the lake was soon regained by the Russians, it was never actually used.

In Moscow, a circular line had been built around the city just before the war connecting the existing lines stretching fan-like out of the city and this proved vital in maintaining links between different parts of the country after the Germans cut off most of the main lines. When the Red Army went on the offensive, the Russian railway troops regauged thousands of miles of line – indeed some sections of track were regauged numerous times as territory was won and lost – including parts of the Polish and German rail networks. Indeed, Stalin travelled to the Potsdam peace conference in a Russian train.

The need for effective railways during the invasion was made all the greater because of that great barrier to smooth transport, mud, whose impact on the outcome of the war cannot be underestimated. Not only was it a frequent obstacle on the roads, but at times it even prevented tanks from moving. Undoubtedly, better roads would have improved the supply situation but not solved it. As Deighton suggests, ‘the virtual absence of paved roads meant that mud was an obstacle on a scale never encountered in Western Europe’. Only more railways with greater capacity could have tipped the balance, something that was not within Hitler’s ability to change. Each of the three army groups stalled after initial advances as they waited for the infantry to catch up, allowing the Russians to regroup or even counter-attack. Even if Hitler, as some of his generals recommended, had decided to focus all his forces on one target, Moscow, the lack of logistical capacity, especially railways, would have saved the city from invasion.

The failure to complete the invasion before the winter of 1941-2 set in proved to be the turning point of the war. There would be big battles such as Stalingrad and Kursk, and the siege of Leningrad would continue, but essentially the German advance was checked along a vast but not entirely stable front that stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and when the war of movement resumed, it was a westward push by the Red Army rather than any continued advance by the Germans.