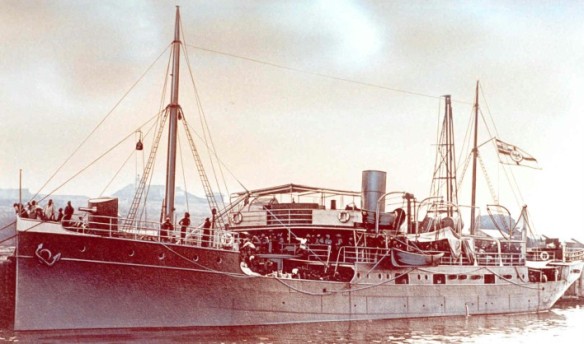

Graf von Goetzen

German East Africa and Lake Tanganyika.

Spicer-Simson’s first task was to secure his base. He was aware that the lake was subject to sudden, violent storms that could wreck his frail boats. The Belgians were asked to build a breakwater, which they did by blasting rock from the nearby cliffs. By late December the newly formed harbour, named Kalemie, was ready for use. On Christmas Eve Mimi and Toutou were launched and completed their trials satisfactorily. Christmas Day was spent in the traditional manner, but on 26 December the Belgians reported a steamer moving down the lake from the north. As the distance closed, the image hardened into the Kingani, engaged in a routine examination of the Belgian fortifications at Lukuga.

Spicer-Simson let her pass, then followed at a distance with Mimi and Toutou, widely separated so that the enemy would have to split his fire between them. A sudden belch of smoke from Kigani’s funnel and a steady turn to port indicated that she was simultaneously trying to escape and bring her gun into action. At 2,000 yards the motor boats opened fire. Immediately, their crews made the unwelcome discovery that unless their 3-pounders were fired directly ahead their recoil could cause damage to their flimsy hulls. Coupled with the need to dodge the German fire, this meant that at first their rate of fire was limited to about one round per minute. Kigani was engaging Toutou with her 37mm gun and firing small arms at Mimi, without hitting either. The advantages of speed and firepower possessed by the British boats now began to tell. With the range down to 1,100 yards, Mimi slammed a shell through the enemy’s gunshield, killing the ship’s captain and two petty officers. When another round killed the warrant officer who had attempted to take command, Kigani’s native crew began jumping overboard and swimming for the shore. The ship’s chief engineer then emerged and hauled down the German colours. Toutou came alongside to escort the prize into Kalemie where, taking in water rapidly from a shell hole in her port bunker, she was beached in just sufficient time to prevent her sinking.

It was unfortunate that Spicer-Simson chose this particular moment to boast openly to his men about his prowess as a gunnery expert, for it had been the 3-pounder gun layers who deserved all the credit, such corrections as he had given being drowned out by the roar of the Thornycroft engine. This was bad enough as they had little enough liking for him anyway, but he could hardly have avoided the contempt in their eyes when he took an ornate gold ring from the finger of the dead German captain and slipped it on his own.

Having been patched up and made watertight, Kingani was given the new name of Fifi and suitably rearmed. The Belgians contributed a 12-pounder gun from one of their coast defence batteries and this was mounted forward while the blind spot aft was closed with a spare 3-pounder. On 14 January 1916 one of the lake’s periodic storms swept down its length, battering Toutou against the breakwater and causing sufficient damage for her to remain out of commission for a while. Fifi began dragging her anchor but good seamanship got her clear of the harbour and, having put out a sea-anchor, she managed to ride out the gale.

Shortly after dawn on 9 February the Belgian lookouts reported Hedwig von Wissmann coming down the lake. The day’s heat was building up when Spicer-Simson boarded Fifi and immediately set off to intercept her, accompanied by Lieutenant A.E. Wainwright in Mimi. The Germans believed that the former Kingani had been sunk by Belgian coast defence batteries and were looking for some evidence to support the theory. Heat haze and thermals above the flat surface of the water prevented the German captain, Lieutenant Odebrecht, from seeing his opponents until they were only 4 miles distant. He immediately reversed course and headed for Kigoma.

The funnels of both steamers began to pour black smoke as oil-soaked wood balks were flung into their furnaces to raise boiler pressure quickly. Wainwright, taking full advantage of Mimi’s speed, forged ahead, opening fire at 3,000 yards range, beyond which the enemy’s stern-mounted 37mm gun could not reply. This seems to have produced results, for Odebrecht began making a series of short turns to starboard to bring his forward 6-pounders into action. Whenever this happened, Wainwright turned to starboard and the enemy shells burst in empty space. These brief pauses enabled Fifi to catch up. Wainwright drew alongside and shouted to Spicer-Simson that his 12-pounder shells were falling well ahead of the enemy. No doubt the seamen concealed their pleasure that their resident gunnery expert had been found wanting by a junior reserve officer, but the appropriate correction was made and the 12-pounder’s next round produced dramatic results. It punched a hole into the enemy’s hull to explode in his engine room and blew a hole in her side. Burning fiercely, her steering gear wrecked and her engines stopped, Hedwig von Wissmann fell away to starboard in a sinking condition and fifteen minutes later disappeared below the surface of the lake. Odebrecht, fifteen Germans and eight native crewmen were rescued from the water.

It would have been quite natural for Zimmer to wonder what had happened to the rest of his flotilla. When, the following day, Graf von Gotzen came down the lake, the British crews were confident that they could deal with her, despite her much larger size. Inexplicably, Spicer-Simson stubbornly refused to leave the harbour although repeatedly urged to do so by his officers. No reason was offered for his decision and the German ship was permitted to retreat back over the horizon. Not for the last time, the British officers and men felt that their commander had brought shame on them.

As the balance of power on the lake had now shifted in favour of the Allies, it was decided to commence land operations against German East Africa. The British invaded from Kenya in the north and Rhodesia in the south while the Belgians invaded from the north-west. Spicer-Simson, now promoted to commander, a recipient both of the Distinguished Service Order and the Belgian Croix de Guerre with Three Palms, was ordered to ferry stores north to Tongwe where the Belgians were constructing a seaplane base. From this a number of air attacks were mounted on the Graf von Gotzen which, it was claimed, had sustained bomb damage. Whatever the truth, Zimmer scuttled her outside Kigoma harbour.

In the meantime, Spicer-Simson had been ordered to take his flotilla south to Kituta in Rhodesia and support operations to capture the German base of Bismarcksburg, with the specific task of ensuring that the enemy garrison did not escape by means of the lake. On 5 June his three craft arrived off the enemy port but were unable to make contact with any of the Rhodesian troops. On the other hand, inside the harbour there were five dhows that the German regularly used to transport their troops. They were a sitting target but Spicer-Simson refused to open fire on them, nor would he permit his officers to do so on the grounds that this would bring their craft within range of the guns in the whitewashed fort overlooking the harbour. The flotilla withdrew to Kituta and did not return to Bismarcksburg until 9 June, the day before Spicer-Simson believed that the Rhodesians would reach the area. To his horror, he found that the Germans had gone, as had the dhows, and it was the Union Flag that now flew above the fort. On entering the harbour the flotilla was met by an infantry officer who clearly had little respect for Spicer-Simson. Why, he wanted to know, had he permitted the Germans to escape the previous night when the Rhodesians had them boxed in the landward? Obviously, no reasonable explanation could be offered and Spicer-Simson was told to report to a Colonel Murray in the fort. Unwisely, the Commander chose not to change out of his skirt so that when he entered the courtyard he was subjected laughter and yells of derision from the Rhodesian infantrymen relaxing in the shade. No one knows what passed between Murray and Spicer-Simson but the latter emerged from the discussion ashen and incoherent.

After this, his actions became so erratic that the expedition’s medical officer recommended that he should be sent home on the grounds of nervous debility, which covered a multitude of sins. Following his treatment, he returned to his desk at the Admiralty, still sporting the ring he had taken from the dead German captain. In due course he received prize money for the capture of the Kingani and some smaller craft, as well as head money, based on the number of enemy casualties inflicted. Yet more money resulted from press interviews and lectures in which a very different gloss was put on the Graf von Gotzen and Bismarcksburg episodes. Finally, he had his portrait painted in naval full dress, including a cocked hat. Despite his unfortunate personality, these rewards should not be begrudged him as he had successfully executed a mission many of his peers thought impossible, without losing a man. Yet John Lee, the architect of the mission, received nothing.

The story inspired the author C.S. Forester to write his novel The African Queen, which became a film of the same name. Two of the original story’s participants survived the war. Toutou was despatched by rail to Cape Town where she was installed at Victoria Docks having received a wash and brush up and a polished plate inscribed as follows: ‘This launch served in the East African Campaign as an armed cruiser. Captured and sank two German gunboats with the assistance of sister launch Mimi.’ Before the Germans scuttled Graf von Gotzen outside Kigoma harbour they applied a thick coating of grease to her machinery, clearly intending that one day she should be raised and taken back into service. That day came in 1924 when she was raised by a Royal Navy salvage team. Disarmed, restored, renamed Liemba and given a slightly more modern appearance, she plied the lake until 2010 when she was finally withdrawn after a century of service.