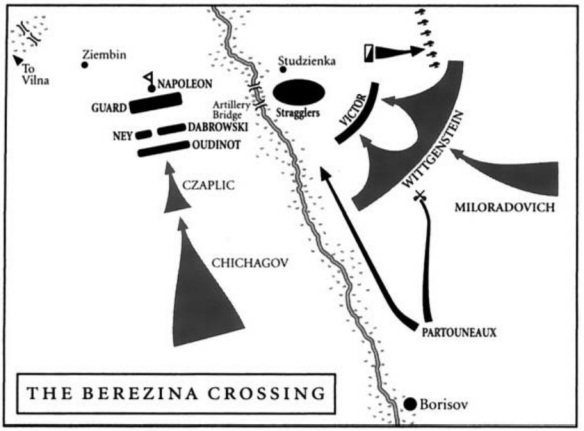

Victor’s 9th Corps also arrived in the late afternoon and took up defensive positions covering the approaches to the bridges. It had left one division, about four thousand men under General Partouneaux, outside Borisov to mislead the Russians, and this was to follow on under the cover of night.

As most of the army was across by that evening, the gendarmes opened the bridges to the stragglers, cantinières, wounded and civilians. But having settled down by their fires, and seeing that their encampment was defended by Victor’s men, most did not avail themselves of the opportunity, preferring to spend a peaceful night where they were. Some, like the cantinière of the 7th Light Infantry who had gone into labour that evening, had no choice. ‘The entire regiment was deeply moved and did what it could to assist this unfortunate woman who was without food and without shelter under this sky of ice,’ wrote Sergeant Bertrand. ‘Our Colonel [Romme] set the example. Our surgeons, who had none of their ambulance equipment, abandoned in Smolensk for lack of horses, were given shirts, kerchiefs and anything people could come up with. I had noticed not far away an artillery park belonging to the corps of the Marshal Duc de Bellune [Victor]. I ran over to it and, purloining a blanket thrown over the back of one of the horses, I rushed back as fast as I could to bring it to Louise. I had committed a sin, but I knew that God would forgive me on account of my motive. I got there just at the moment when our cantinière was bringing into the world, under an old oak tree, a healthy male child, whom I was to encounter in 1818 as a child soldier in the Legion of the Aube.’

A remarkable degree of order and even normality reigned over the Grande Armée as it settled down for the night on both sides of the river. A key factor was undoubtedly the presence of the Emperor and the fact that he had visibly taken the initiative, which led everyone to expect great things and kept spirits high. ‘We are still capable of fun and a good laugh,’ noted Jean Marc Bussy, a Swiss voltigeur sitting around a campfire with his comrades on the western bank of the river. One cannot but admire him. ‘When night fell, each soldier took his knapsack for a pillow and the snow as a mattress, with his musket in his hand,’ wrote his comrade Louis Begos of the 2nd Swiss Regiment. ‘An icy wind was blowing hard, and the men pressed up against each other for warmth.’

All that day Napoleon had anxiously listened for the sound of cannon announcing the approach of the Russians. But there was still no sign that Chichagov had realised his mistake. The note he penned to Marie-Louise that evening shows no trace of anxiety.

What he might have heard, had it not been over ten kilometres away, was the end of one of Partouneaux’s brigades, which had been holding Borisov. The Partouneaux division, which had only entered Russia recently, had suffered the depressing effects of the conditions in rapid order. The men had been in fine spirits when they had reached Borisov a few days before. At one point they were charged by some Russian cavalry and formed squares. One of the Russian officers, unable to control his wounded mount, had crashed into the middle of the square, where he was pinned to the snow under the thrashing animal. A couple of French soldiers pulled him clear, dusted the snow off his uniform and then went back to their posts in the firing line. The officer bided his time until the French were occupied by another Russian charge and, slipping between them, ran, hopping through the deep snow, to rejoin his own men, at which the entire French square burst into laughter.

But a couple of days later, as they camped out in a windswept spot without fires or food, their mood was very different. ‘Some wept, crying out plaintively to their parents; some went raving mad; some died under our eyes after a horrible agony,’ according to one of them. Having held Borisov as long as was necessary, the division had begun to withdraw on the afternoon of 27 November. But one of its brigades lost its way and walked straight into the midst of Wittgenstein’s army. After a running battle in which it lost half its number, it was forced to surrender. The men were stripped, beaten and marched off into captivity. One of its regiments, the 29th of the Line, was made up largely of men who had only recently been released from prison hulks in England, having been captured in Saint-Domingue in 1801. ‘Luck, one has to admit, seems to have abandoned these poor fellows,’ remarked Boniface de Castellane.

Chichagov had by now realised that he had been duped. Most of his men were still at Borisov and points further south, but he ordered Czaplic to attack the French forces which had already got across the Berezina, promising to send reinforcements. But his men, who had been force-marched some fifty kilometres south and were now ordered to hurry back, made slow progress through the heavy snow. There was much grumbling and even the threat of mutiny. ‘One of the regiments I had ordered to go and reinforce Czaplic hesitated and then refused outright to move,’ Chichagov recorded. ‘My exhortations having produced no effect, I was obliged to have recourse to the threat of firing on it. I had cannon unlimbered and levelled at it from behind.’ Some of Chichagov’s units did however come up to reinforce Czaplic that night, and more were on the way.

Before dawn on 28 November, as Oudinot finished gulping down the warming soupe à l’oignon his staff had cooked up at their campfire, the first shots resounded on the western bank of the Berezina as a reinforced Czaplic pushed northward under a strong artillery barrage. Oudinot organised a defence, and led his men out under murderous fire from the Russian guns, but he was hit by a shell splinter – his twenty-second wound. Napoleon, who was on the scene, put Ney in command with orders to hold the Russians back at all costs in order to cover the retreat of the remainder of the Grande Armée, the stragglers and, finally, Victor’s men.

It was a tall order. Czaplic and Chichagov had over 30,000 fresh troops who had not suffered any serious military losses, and all Ney could put up against them were 12 to 14,000 emaciated and half-frozen remnants: all that was left of Oudinot’s 2nd Corps, the Dabrowski division and a few survivors from Poniatowski’s 5th Corps, the Legion of the Vistula, and a handful of other units (his own 3rd Corps had all but ceased to exist, with one regiment numbering forty-two men, another only eleven, and the 25th Württemberg Division’s six regiments of infantry, four of cavalry and divisional artillery park down to a grand total of 150 men). Three-quarters of them were not even French. Almost half were Poles, there were four regiments of Swiss, a few hundred Croats of the 3rd Illyrian Infantry, some Italians, a handful of Dutch Grenadiers and Colonel de Castro’s 3rd Portuguese Regiment. This motley bunch rose to the occasion magnificently.

The Russians under General Czaplic, a Pole in Russian service, advanced in force through the wooded terrain, but Ney sent in Dabrowski’s Poles, who forced them back to their starting positions. Two more divisions sent by Chichagov then arrived on the scene, Voinov’s and Shcherbatov’s. They launched a massed attack, supported by an artillery bombardment which sent splinters of pine and fir shooting murderously through the ranks of the Poles. Dabrowski was wounded and handed over command to General Zajaczek, who was soon carried off the field himself with a shattered leg, leaving General Kniaziewicz in command, but he too was put out of action. As the Poles fell back in hand-to-hand fighting among the trees, Ney reinforced them with whatever units came to hand.

Although these were numerically weak, they displayed barely believable spirit. The 123rd Dutch Light Infantry regiment, down to eighty men and five officers, cheered as it went into action. At one point a cannonball shattered the trunk of a huge tree heavy with snow, which came crashing down and buried a dozen men of the French 5th Tirailleurs, but they all clambered out from under the snow laughing like children amidst the bursting shells. When, a few moments later, a shell killed their Colonel’s horse, throwing him to the ground, they rushed forward to his aid, but he sprang up and shouted at them: ‘I am still at my post, so let everyone remain at theirs!’

In order to relieve the pressure on them, Ney sent in General Doumerc with his cuirassiers and three regiments of Polish lancers. They charged the Russians, sowing panic and driving them back. Czaplic was wounded and General Shcherbatov was captured, along with two thousand others and a couple of standards. A countercharge by Russian hussars and dragoons steadied the situation, but the Swiss regiments, which had now taken over the French front line, supported by the Dutch, the Croats and the Portuguese, held their ground.

The battle raged all day, with the Swiss making no fewer than seven bayonet charges when they ran out of cartridges. ‘It was worse than a butchery,’ noted Jean Marc Bussy. ‘There was blood everywhere on the snow, which had been trampled as hard as a beaten earth floor by all the advancing and retreating … One hardly dared to look to right or left, out of fear of seeing that a comrade was no longer there.’ The fighting was so hot that they forgot about the freezing temperatures, and they kept their spirits up with shouts of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ As death closed in around them in the icy wood, the Swiss broke into the strains of the old mountain lied ‘Unser Leben Gleicht der Reise’. The fighting did not stop until eleven o’clock that night, when the Russians, having failed to push the defenders back one step from their morning positions, finally gave up.

It was a magnificent victory for the French, but a bitter one. As they made fires and dragged in their wounded to dress them as best they could, they knew that they would have to leave them behind the following day. The four Swiss regiments had lost a thousand men, and mustered no more than three hundred between them. ‘We hardly dare speak to each other, for fear of hearing of the death of another of our comrades,’ recalled Bussy. Of the eighty-seven voltigeurs in his company who had laughed around their campfires the previous night, just seven were left alive. The 123rd Dutch Light Infantry had ceased to exist. The Dutch Grenadiers were down to eighteen officers and seven other ranks.

Their heroics were honourably matched by Victor’s men defending the crossings on the other bank. They numbered no more than eight thousand men, mostly Badenese, Hessians, Saxons and Poles, and were facing an army over four times that. But here too morale was unaccountably high. They were attacked at nine o’clock in the morning and held their positions until nine that evening against overwhelming odds.

Wittgenstein’s first attacks were concentrated on the Baden brigade, commanded by the twenty-year-old Prince Wilhelm of Baden, which was holding the right wing of the French defence perimeter. Prince Wilhelm’s men had been greatly cheered when, three days before, they had come across a convoy from Karlsrühe with food and supplies of every sort. The men were able to exchange worn-out uniforms, overcoats and boots for new ones, and to help themselves to food and delicacies. ‘Every officer had received something from home and everyone jumped on the packages destined for them,’ wrote Prince Wilhelm. ‘Thus it was that I saw Colonel Brucker, standing on one of the wagons, open up a large box which I assumed to be full of victuals, and from it he drew a wig and, quick as a flash, he removed the old one he had on his bald head and donned the new one, trying to mould it to his head with his hands.’ Prince Wilhelm himself was in a good mood that morning as his greyhounds had caught a hare, which he had eaten and washed down with wine that had come in the convoy. Although they were now attacked by overwhelming forces, he and his men stood firm, at the cost of terrible losses.

Hoping no doubt to break the determination of the defenders, Wittgenstein established a strong battery beyond the left wing of Victor’s line, and began shelling the area behind it. This was by now occupied by a dense mass of thousands of people, horses and vehicles, up to four hundred metres deep, stretching for over a kilometre along the riverbank. Shortly after midday, Russian shells began to rain down on this vast encampment, bringing hideous destruction as they exploded among the mêlée, killing and maiming people and horses, sending splinters of wood and glass from shattered carriages flying through the air. It was the end of the road for many of the civilians. Captain von Kurz watched in horror as a beautiful young woman with a four-year-old daughter had the horse she was riding killed and her thigh shattered by a Russian shell; realising that she could go no further, she untied the blood-soaked garter from her leg and, after kissing her tenderly, strangled her child and, clutching her in her arms, lay down to await death. Seeing her wagon stuck, Baska, the cantinière of the Polish Chevau-Légers, cut her horse free and, taking her small son in her arms, rode into the Berezina on it. She got more than halfway across before the horse began to drown and sank beneath the surface, throwing her and her son into the water, from which only she was able to wade ashore.

Panic broke out, and a mad rush for the bridges ensued, with people driving their wagons and horses over the corpses of men and beasts, over the wreckage of carriages and abandoned luggage. This merely served to compact the mass pressing around the bridge-ends like a flock of frightened sheep, and now every Russian shell found a target. The massacre continued until Victor managed to mount an attack on the Russian batteries which forced them to pull back out of range.

Although the shelling had stopped, that did not relieve the pressure on the crossings. A mass of people, horses and vehicles converged on the bridges, with those behind pushing forward continuously, so that it was not possible to avoid trampling those who stumbled and fell. ‘Anyone who weakened and fell would never rise again, as he was walked over and crushed. In this dense mass even the horses were so hard-pressed that they fell over, and, like the men, they too could not get up again,’ remembered Sergeant Thirion. ‘By the efforts they made to do so they brought down men who, being pushed from behind, could not avoid the obstacle, and neither men nor horses ever rose again.’

Lieutenant Carl von Suckow had become separated from his fellow Württembergers and was caught in the crush. ‘I found myself being dragged along, jostled and even borne along at some moments – and I do not exaggerate,’ he wrote. ‘Several times I felt myself being lifted off the ground by the mass of people around me, which gripped me as though I had been caught in a vice. The ground was covered in animals and men, alive and dead … At every moment I could feel myself stumbling on dead bodies; I did not fall, it is true, but that was because I could not. It was only because I was held up on every side by the crowd which pressed in on me. I have never known a more horrible sensation than that I felt as I walked over living beings who tried to hold on to my legs and paralysed my movements as they attempted to raise themselves. I can still remember today what I felt on that day as I placed my foot on a woman who was still alive. I could feel the movements of her body, and I could hear her scream and moan: “Oh! take pity on me!” She was clinging to my legs when, suddenly, as a result of a strong thrust from behind, I was lifted off the ground and wrenched from her embrace.’ As he found himself being forced back and forth near the entrance to the bridge, he experienced ‘the first and only real moment of despair I had felt during the entire campaign’. He finally grabbed the collar of a tall cuirassier who was clearing a path for himself with a mighty stick, and was dragged onto the bridge and over the river.

As those caught in the throng could not see in front of them, many found that they came to the river not at the head of one of the bridges, but on the bank. Since they were still being pushed from behind by others they were forced into the water, through which they tried to wade over to the bridges and clamber on from the side. The crush on the bridges themselves was just as great, and those walking in the middle were pressed from both sides as those at the sides moved along facing outwards and pushing inwards with their backs in order not to be thrown into the water.

Those who could not stand up for themselves did not have much of a chance, and many who had somehow managed to make it thus far perished here. A Saxon under-officer named Bankenberg, who had had both legs amputated above the knee after Borodino, had been rescued from Kolotskoie by his comrades. He had been tied onto a horse, and survived all the tribulations of the retreat with courage, but they lost sight of him at the Berezina, and he was never seen again.

In the afternoon Wittgenstein mounted a second assault on Victor’s defences, and the Baden brigade was finally forced to give ground. But Victor sent in the Brigade of Berg, made up of Germans and Belgians, and then his remaining cavalry. This, consisting of Hessian chevau-légers and Badenese hussars as well as French chasseurs, no more than 350 men in all, was led into the charge by Colonel von Laroche with such dash that it routed the Russians. A countercharge by Russian cavalry virtually annihilated the Germans, but the French defences had been saved, and as night fell Victor’s men were occupying the same positions as they had that morning.

Many of those still hoping to cross found themselves blocked by the barricades of abandoned vehicles, dead horses and human corpses which impeded access to the bridges, and as night began to fall and the fighting died down, they too began to settle down for the night, in the hope that crossing might be easier in the morning.

Victor received the order to withdraw, but seeing the numbers of non-combatants still on the eastern bank, he decided to hold it until daybreak, thus giving them a chance to cross. General Eblé and 150 of his pontoneers cleared the bridges of the corpses, carcases and vehicles that had accumulated on them in the afternoon rush. In order to clear the approaches they dragged many of the abandoned vehicles onto the bridges and then pushed them into the water, and unharnessed and led to the west bank as many of the abandoned horses as they could. They had to drag away or push over carriages and wagons that could not be wheeled away, heaving the carcases of horses and human corpses to the side to create a kind of trench between two banks of dead men and beasts.

At nine o’clock that evening Victor began sending some of his units, his supply wagons and his wounded across, and by one o’clock in the morning of 29 November he had only a screen of pickets and a couple of companies of infantry left with him on the east bank. He and Eblé urged the remaining stragglers to cross, warning them that the bridges would be burnt at first light, but most of them were either too tired or too apathetic. ‘We no longer knew how to appreciate danger and we did not even have enough energy to fear it,’ wrote Colonel Griois, who remained by his fireside along with other comrades from Grouchy’s corps. Others were apparently too absorbed by other preoccupations, and the surgeon Raymond Pontier swore that he saw two officers fighting a duel instead of crossing.

At about five o’clock in the morning, Eblé ordered his men to start setting fire to wagons and carriages still littering the eastern bank in order to wake up the non-combatants, and to shout loudly that the bridges would only be open for a couple of hours. A few availed themselves of this, but at six o’clock, when Victor withdrew his pickets and marched across, the remainder began to realise that their last chance had come. A mass of them swarmed onto the bridges, pushing and shoving to get over. Sergeant Bourgogne, who had come back to see if he could pick up any stragglers from his regiment, watched as a cantinière, holding onto her husband who had their child on his shoulders, was pushed into the icy water, dragging her family with her, and as a wagon with a wounded officer was tipped over, horse and all, to disappear instantly beneath the ice floes.

Eblé had orders from Napoleon to burn the bridges at seven o’clock, as soon as Victor’s last man was across, but he could not bear to leave so many of his countrymen stranded, so he delayed the execution of the order until 8.30. By then Wittgenstein’s men could be seen advancing towards the bridges on the opposite bank, and groups of cossacks were already picking over the booty left behind in the wagons and carriages littering the approaches. As Eblé fired the bridges, some of those still on them tried to struggle through the flames, others threw themselves into the water in order to swim the last stretch, while hundreds of others were pushed into it by the pressure of those behind who did not know the bridges now led nowhere.

The morning after the French had marched off, Chichagov rode up to the scene of the crossings. He and his entourage would never forget the grim spectacle. ‘The first thing we saw was a woman who had collapsed and was gripped by the ice,’ recalled Captain Martos of the engineers, who was at his side. ‘One of her arms had been hacked off and hung only by a vein, while the other held a baby which had wrapped its arms around its mother’s neck. The woman was still alive and her expressive eyes were fixed on a man who had fallen beside her, and who had already frozen to death. Between them, on the ice, lay their dead child.’

Lieutenant Louis de Rochechouart, a French officer on Chichagov’s staff, was deeply shaken. ‘There could be nothing sadder, more distressing! One could see heaps of bodies, of dead men, women and even children, of soldiers of every formation, of every nation, frozen, crushed by the fugitives or struck down by Russian grapeshot; abandoned horses, carriages, cannons, caissons, wagons. One would not be able to imagine a more terrifying sight than that of the two broken bridges and the frozen river.’ Peasants and cossacks were rummaging through the wreckage and stripping the corpses. ‘I saw an unfortunate woman sitting on the edge of the bridge, with her legs, which dangled over the side, caught in the ice. She held to her breast a child which had been frozen for twenty-four hours. She begged me to save the child, not realising that she was offering me a corpse! She herself seemed unable to die, despite her sufferings. A cossack rendered her the service of firing a pistol at her ear in order to put an end to this heartbreaking agony!’ Everywhere there were survivors on their last legs, begging to be taken prisoner. ‘“Monsieur, please take me on, I can cook, or I am a valet, or a hairdresser; for the love of God give me a piece of bread and a shred of cloth to cover myself with.”’

Estimates of the numbers left behind on the eastern bank of the river vary wildly, from Gourgaud’s dismissive assertion that only two thousand stragglers and three guns failed to get across, Chapelle’s estimate of four to five thousand along with three to four thousand horses and six to seven hundred vehicles, to Labaume’s of 20,000 and two hundred guns, which is certainly too high. Chichagov recorded that nine thousand were killed and seven thousand taken prisoner, which seems closer to the mark. Most are now agreed that during the three days the French lost up to 25,000 (including as many as 10,000 non-combatant stragglers) on both banks, of which between a third and a half were killed in action. Russian losses, all inflicted in the fighting, were around 15,000.

The crossing of the Berezina was, by any standards, a magnificent feat of arms. Napoleon had risen to the occasion and proved himself worthy of his reputation, extricating himself from what Clausewitz called ‘one of the worst situations in which a general ever found himself’. His soldiers had fought like lions. But it was above all a triumph for Napoleonic France, and its ability to create out of the rabble of a score of nations armies which were in every way superior to their opponents, which fought intelligently as well as loyally, and which in this instance did so as though they had been defending their own wives and children. ‘The strength of his intellect, and the military virtues of his army, which not even its calamities could quite subdue, were destined here to show themselves once more in their full lustre,’ as Clausewitz put it.