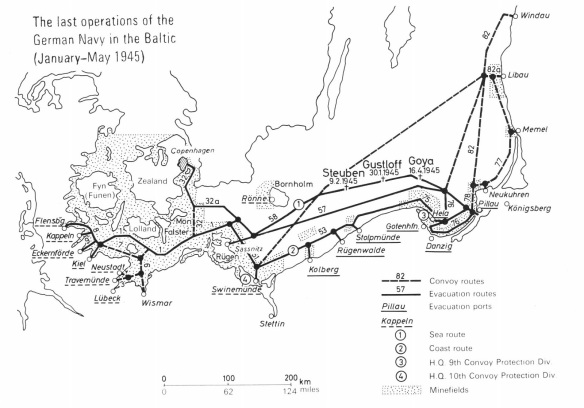

By the beginning of April the Baltic was the only area where the Kriegsmarine could make a real contribution to the war. It couldn’t win it any longer, but it could do something to rescue its comrades in arms and other German citizens from falling into the hands of the dreaded Soviet enemy. All around the eastern shoreline of the Baltic from Courland in the north to East Prussia in the south the various campaigns were beginning to show very similar responses. Soviet attacks were held for a time and possibly even beaten off (as had been the usual case in Courland) but eventually the incessant pressure told and a breakthrough was made. Amazingly in these extraordinarily dramatic circumstances, the logistical exercise that was the evacuation operation continued in unabated fashion from Windau (Ventspils) and Libau (Liepāja) in Latvia south to Pillau. Disruptions and delays in the schedule of sailings became more pronounced as the war closed in on the German forces. Once a renewed drive on Königsberg began on 6 April 1945, for example, the situation at Pillau became increasingly critical. Within three days the city was surrounded and on 10 April its defenders capitulated. Faced with a swelling refugee population and the necessity of trying to get as many people away from the port as possible before it fell, German ships kept on returning for another fortnight before the town and its harbour were finally abandoned to the Soviets on 25 April. By that time, however, 451,000 refugees and 141,000 wounded servicemen had been evacuated from this icefree port in the four months that the operation had lasted. It was a quite staggering achievement and reflected the pivotal role Pillau had played in the entire evacuation operation. As the escape routes through that port and others around the Gulf of Danzig were being choked off, however, the Germans had been forced to rely upon the facilities at Hela to keep the process going. These went into overdrive as the port became besieged with refugees from the region of the Lower Vistula. As they did so, the Soviets immediately responded by increasing their aircraft sorties over the port. In the process five transports, two supply ships and a hospital ship were lost along with a handful of other craft. Notwithstanding these losses, Hela performed with distinction. In the month of April alone as many as 387,000 evacuees left the port for the west. These sailings were chillingly tense affairs with the ships hounded by air and sea attacks and with survival never guaranteed. Nonetheless, the alternative – of not attempting to run the Allied gauntlet and accepting captivity at the hands of the Soviets – was unthinkable. For every ship that was sunk on passage from Hela, many more somehow managed to get through with their precious human cargo. There was little time to waste and the Germans herded the refugees aboard with admirable and startling efficiency. In so doing they set a record of embarking 28,000 passengers in a single day (21 April) and ran it close a week later when a mere seven steamers collected a further 24,000. They were the lucky ones. Many more who tried to leave in the last days of the war were nothing like as fortunate.

On the day that the Soviets completed their encirclement of Berlin (25 April), Dönitz and the OKM were forced into beginning a policy of destruction and deprivation. Principal units of their Kriegsmarine were not going to be allowed to fall into the hands of the hated communists and so those ships that couldn’t be moved and were most in danger of being seized by the Red Army – such as the uncompleted aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin – were blown up in Stettin (Szczecin) along with four steamers and other smaller vessels. Schlesien and Lützow were the next to go. Schlesien, after being gravely damaged by a British air ground mine as she attempted to make her way into the Griefswalder Bodden on 2 May, was towed back to Swinemünde and beached as the Lützow had been just over a fortnight before. They shared the same fate again when both were blown up on 4 May. It signified that Swinemünde was finished as a German base.

That didn’t stop about sixty of them in the Baltic from opting to try to get to Norway. In making this journey they found themselves, as did many other surface vessels, confronted by swarms of RAF bombers seeking to destroy them. In a four day blitz (2–6 May) a mixture of Beaufighters, Liberators, Mosquitoes and Typhoons did just that. Seventeen of the U-boats, eleven steamers, three minesweepers, a gunboat and an MTB, along with other minor vessels, were set upon anywhere from the Baltic to the Kattegat and didn’t survive the experience.

Those submariners in German ports from Wilhelmshaven and Bremerhaven in the west to Lübeck and Warnemünde in the east, for instance, were left with the defiant, if doleful, task of scuttling their own craft. In the first three days of May as many as 135 Uboats perished in this way. Even more extraordinary scenes greeted the British XII Corps as they occupied the city of Hamburg on 3 May when as many as nineteen floating docks, fifty-nine large and medium-size ships and roughly 600 smaller vessels littering the harbour were scuttled or blown up by German forces within the port. The next day (4 May) when the U-boat captains in the area heard about the signing of the surrender document applicable to German forces in Denmark, Holland and northwest Germany, they put the coded operation Regenbogen (Rainbow) into practice scuttling eighty-three U-boats in fourteen different locations stretching from the Danish port of Aarhus in the Kattegat southeast to Lübeck in the Baltic and west to the outer Weser in the North Sea.

While this was going on in the North Sea and the Belts around Denmark, every kind of ship from naval barges, freighters and transports to destroyers, torpedo boats and much smaller vessels were making their way either to or from Hela in the Baltic with the last of the refugees and troops to be moved from the east to relative safety in the west. By the time the German unconditional surrender came into force on 8 May some 1,420,000 refugees had made their way by sea to the west from the Pomeranian coast and the ports around the Gulf of Danzig in the period from 25 January to the end of the war. In addition, at least another 600,000 had also been evacuated over much smaller distances within the Gulf of Danzig itself. It had been a quite phenomenal achievement. It took raw courage to keep going back into the dangerous maelstrom that swirled around the eastern half of the Baltic. It ended characteristically with the last two convoys containing sixty-one small naval vessels leaving Windau and four convoys of sixty-five similar craft escaping from Libau on 8 May with a total of 25,700 troops and other refugees on board. Of these only a few of the smallest and slowest ships, containing roughly 300 men, were caught by the Soviets on the following day – the rest made it through safely to the west.